Class 2: Mystic Twilight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Gauguin

Sarah Kapp Art History and Visual Studies Major (honours) Business Minor De-Mythicizing the Artist: Presented March 6, 2019 This research was supported by the Jamie Cassels Undergraduate Research Award University of Victoria Supervised by Dr. Catherine Harding How Gauguin Responded to the Art Market Assistance from Dr. Melissa Berry Political Conditions Introduction Imperialism and Primitivism in the Late-Nineteenth Century Like celebrities, famous artists face rumours and myths Gauguin’s stylistic innovations were just one component of his self-promotional endeavor that overwhelm their public reception. Vincent van Gogh that appeared in the Volpini Suite. It was his engagement with ‘primitive’ subject- has become inextricably linked to the tale of the tortured matter—which included depictions of local peasant and folk culture—that served as a soul who sliced off his ear; Pablo Picasso to the tale fashionable and marketable technique (Perry 6). In the 1889 suite, Gauguin depicted of the womanizing innovative artist; and Salvador Dalí people in their daily surroundings, including: Breton peasant women chatting, Martinican as the eccentric artist who did too many drugs. This women carrying baskets of fruit, and women from Arles out walking (Juszczak 119). research dismantles the myth of Paul Gauguin (1848- After his creation of the Volpini Suite, Gauguin’s use of ‘primitive’ subjects intensified, 1903), who, in the late-twentieth century, became ultimately becoming a defining feature of his artistic practice. Gauguin’s work in the the target of feminist and post-colonialist theorists, Volpini Show correlated to contemporary ideas about the ‘primitive’. The Exposition who criticized him for sexualized depictions of young Universelle juxtaposed the newly built Eiffel Tower and the Gallery of Machines with women, as well as ‘plagiarizing’ and ‘pillaging’ the art ethnographic exhibits from around the world (Chu 439). -

The Fijian Frescoes of Jean Charlot Caroline Klarr

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Painting Paradise for a Post-Colonial Pacific: The Fijian Frescoes of Jean Charlot Caroline Klarr Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE PAINTING PARADISE FOR A POST-COLONIAL PACIFIC: THE FIJIAN FRESCOES OF JEAN CHARLOT By CAROLINE KLARR A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester 2005 Copyright 2005 Caroline Klarr All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Caroline Klarr defended on April 22, 2002 Jehanne Teilhet-Fisk Professor Directing Dissertation (deceased) J. Kathryn Josserand Outside Committee Member Tatiana Flores Committee Member Robert Neuman Committee Member ______________________ Daniel Pullen Committee Member Approved: ________________________________________ Paula Gerson, Chair, Department of Art History ________________________________________ Sally E.McRorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to Dr. Jehanne Teilhet-Fisk Ka waihona o ka na’auao The repository of learning iii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Jean Charlot’s fresco murals in the Pacific Islands of Hawai’i and Fiji represent the work of a mature artist, one who brought to the creation of art a multicultural heritage, an international background, and a lifetime of work spanning the first seven decades of the twentieth century. The investigation into any of Charlot’s Pacific artworks requires consideration of his earlier artistic “periods” in France, Mexico, and the United States. -

Paul Gauguin: Monotypes

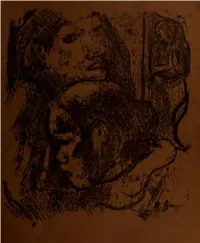

Paul Gauguin: Monotypes Paul Gauguin: Monotypes BY RICHARD S. FIELD published on the occasion of the exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art March 23 to May 13, 1973 PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART Cover: Two Marquesans, c. 1902, traced monotype (no. 87) Philadelphia Museum of Art Purchased, Alice Newton Osborn Fund Frontispiece: Parau no Varna, 1894, watercolor monotype (no. 9) Collection Mr. Harold Diamond, New York Copyright 1973 by the Philadelphia Museum of Art Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-77306 Printed in the United States of America by Lebanon Valley Offset Company Designed by Joseph Bourke Del Valle Photographic Credits Roger Chuzeville, Paris, 85, 99, 104; Cliche des Musees Nationaux, Paris, 3, 20, 65-69, 81, 89, 95, 97, 100, 101, 105, 124-128; Druet, 132; Jean Dubout, 57-59; Joseph Klima, Jr., Detroit, 26; Courtesy M. Knoedler & Co., Inc., 18; Koch, Frankfurt-am-Main, 71, 96; Joseph Marchetti, North Hills, Pa., Plate 7; Sydney W. Newbery, London, 62; Routhier, Paris, 13; B. Saltel, Toulouse, 135; Charles Seely, Dedham, 16; Soichi Sunami, New York, 137; Ron Vickers Ltd., Toronto, 39; Courtesy Wildenstein & Co., Inc., 92; A. J. Wyatt, Staff Photographer, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Frontispiece, 9, 11, 60, 87, 106-123. Contents Lenders to the Exhibition 6 Preface 7 Acknowledgments 8 Chronology 10 Introduction 12 The Monotype 13 The Watercolor Transfer Monotypes of 1894 15 The Traced Monotypes of 1899-1903 19 DOCUMENTATION 19 TECHNIQUES 21 GROUPING THE TRACED MONOTYPES 22 A. "Documents Tahiti: 1891-1892-1893" and Other Small Monotypes 24 B. Caricatures 27 C. The Ten Major Monotypes Sent to Vollard 28 D. -

Vincent Van Gogh, (N) Kazimir Malevich, (O) Salvador Dali, (P) Auguste Renoir

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ Федеральное государственное образовательное учреждение высшего образования «НИЖЕГОРОДСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ ЛИНГВИСТИЧЕСКИЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ ИМ. Н.А. ДОБРОЛЮБОВА» (НГЛУ) М.И. Дмитриева ИСКУССТВО. ЧАСТЬ I. ЖИВОПИСЬ The Arts. Part I. Painting Учебное пособие Издание 3-е, переработанное и дополненное Нижний Новгород 2018 Печатается по решению редакционно-издательского совета НГЛУ. Направления подготовки: 45.03.02 – Лингвистика (профиль ТиМПИЯК), 44.03.01 – Педагогическое образование. Дисциплина: Практикум по культуре речевого общения 1-го иностранного языка (английский язык). УДК (811.111:75) (075.8) ББК 81.432.1-933 Д 534 Дмитриева М.И. Искусство. Часть I. Живопись = The Arts. Part I. Painting: Учебное пособие. 3-е изд., доп. и перераб. – Н. Новгород: НГЛУ, 2018. – 101 с. Предлагаемое учебное пособие предназначено для аудиторной и самостоятельной работы студентов III курса факультета английского языка по теме «Живопись». В пособии рассматриваются различные направления традиционной и современной живописи, творчество отдельных ее представителей, русская и британская живопись, проблемы художника и общества. Система упражнений направлена на совершенствование лексико- грамматических навыков студентов, а также расширение их коммуникативно-языковой и лингвистической компетенции. УДК (811.111:75) (075.8) ББК 81.432.1-933 Автор М.И. Дмитриева, канд. филол. наук, доцент кафедры английского языка Рецензент В.В. Дубровская, канд. пед. наук, доцент кафедры основ английского языка НГЛУ им. Н.А. Добролюбова © НГЛУ, 2018 © Дмитриева М.И., 2018 2 Unit 1. Focus on Vocabulary A GUIDE TO MODERN ART Task 1.1. HOW WELL DO YOU KNOW MODERN ART? Match the trends in art on the left with their definitions on the right and complete the table with the names of the artists who represent them. -

OTSUKA MUSEUM of ART Exhibition List of Works

OTSUKA MUSEUM OF ART exhibition list of works No. Painter Title Place Country 0001 Michelangelo Buonarroti Dividing the Light from the Darkness Cappella Sistina Vatican 0001 Michelangelo Buonarroti Creation of the Sun and the Moon Cappella Sistina Vatican 0001 Michelangelo Buonarroti Parting the Waters Cappella Sistina Vatican 0001 Michelangelo Buonarroti Creation of Adam Cappella Sistina Vatican 0001 Michelangelo Buonarroti Creation of Eve Cappella Sistina Vatican 0001 Michelangelo Buonarroti Original Sin and Banishment from Eden Cappella Sistina Vatican 0001 Michelangelo Buonarroti Sacrifice of Noah Cappella Sistina Vatican 0001 Michelangelo Buonarroti Deluge Cappella Sistina Vatican 0001 Michelangelo Buonarroti Naoh's Drunkenness Cappella Sistina Vatican 0001 Michelangelo Buonarroti Last Judgement Cappella Sistina Vatican 0002 El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) Trinity Museo del Prado Spain 0003 El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) St.Andrew and St.Francis Museo del Prado Spain 0004 El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) Martydom of St.Maurice Museo El Escorial Spain 0005 El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) Burial of Count Orgas Santo Tomé Spain 0006 El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) Annunciation Museo del Prado Spain 0006 El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) Baptism of Christ Museo del Prado Spain 0006 El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) Crucifixion Museo del Prado Spain 0006 El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) Resurrection Museo del Prado Spain 0006 El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) Pentecost Museo del Prado Spain 0006 El Greco (Domenikos -

Buddhist Imagery in the Work of Paul Gauguin

BUDDHIST IMAGERY IN THE WORK OF PAUL GAUGUIN: THE IMPACT OF PRIMITIVISM, THEOLOGY AND CULTURAL STUDIES A THESIS IN Art History Presented to the faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by SARA ANN CAMISCIONI B.A., University of Kansas, 2012 Kansas City, Missouri 2014 © 2014 SARA ANN CAMISCIONI ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BUDDHIST IMAGERY IN THE WORK OF PAUL GAUGUIN: THE IMPACT OF PRIMITIVISM, THEOLOGY AND CULTURAL STUDIES Sara Ann Camiscioni, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2014 ABSTRACT Scholars attribute aesthetics in Gauguin’s work to the 1889 Paris Exposition universelle and Gauguin’s quest for the primitive and “exotic.” This study takes a deeper look at Gauguin and examines the personal context in which his works were created. This will show Gauguin’s immense suffering and unhappiness as a result of separation from family, financial and health struggles. The personal context of the artists’ life, I argue, influenced the appropriation of Buddhist imagery in his work. I examine the visual elements within Gauguin’s work that link his subject matter to Buddhism and look closely at several major works, including Nirvana, Self – Portrait, Caribbean Woman, and Te nave nave fenua that clearly appropriate Buddhist imagery. Gauguin’s incorporation of mudras, color palettes, and other subject matter express his Buddhist sympathies. His appropriation of formal motifs served his spiritual beliefs just as much as his aesthetic purposes. My research draws on recent scholarship on Gauguin, and utilizes the artist’s personal letters and manuscripts. -

Colour Ascetism and Synthetist Colour Colour

Art History Department of Philosophy, History, Culture and Art Studies University of Helsinki COLOUR ASCETISM AND SYNTHETIST COLOUR COLOUR CONCEPTS IN TURN-OF-THE-20TH-CENTURY FINNISH AND EUROPEAN ART Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in the Arppeanum Auditorium on the 6th of June, 2012 at 12 o’clock Helsinki 2012 Opponent Professor Bettina Gockel, University of Zurich Front cover [ !!"#$%& '(& )*" +*% CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................7 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ...............................................................................9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 15 1. Colour Ascetism and Synthetist Colour in Focus ...................................... 15 1.1 On the Dissertation .................................................................21 1.2 Sources .....................................................................................23 2. Methodological Framework and Artists’ Interest in Colour .....................29 2.1 Tradition and Innovation ........................................................37 2.2. Colour Theories and Colour Histories ....................................41 3. Main Concepts: Colour Ascetism and Synthetist Colour ..........................53 4. Finnish Art in the 1890s .............................................................................77 PART I ..............................................................................................................99 -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2003

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2003 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 2003. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 2003 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012200301_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 7 Director's foreword The Van Gogh Museum mounts around six exhibitions every year, covering a wide range of subjects from the history of 19th and early 20th-century art. Many of these are international collaborations with partner museums, often involving loans from across the world. Yet, even for an institution accustomed to mounting large, temporary exhibitions, the show devoted to Van Gogh and Gauguin (The Art Institute of Chicago, 22 September 2001-13 January 2002, Van Gogh Museum, 9 February-2 June 2002) was of an order that fell far beyond the boundaries of our normal experience. In part this was because of the sheer scale of the enterprise and the various logistical challenges presented by this particular undertaking. It was also because the response from the public was almost overwhelming. Over a period of five months, some 739,000 visitors came to see Van Gogh and Gauguin in Amsterdam, making it the busiest art exhibition anywhere in the world in that year. But in the end it was the visual and emotional impact of this encounter between two great yet opposing talents that created an extraordinary show. From the beginnings of their first awareness of each other's art in the 1880s, through the brief but frenetic period when they were together in Arles in 1888, and then on to the end of their careers, the interaction between the two painters was revealed and analysed. -

Gauguin Maker of Myth

Gauguin Maker of Myth National Gallery of Art / February 27 – June 5, 2011 paul gauguin (1848, Paris – 1903, Hiva-Oa, Marquesas Islands) spent a lifetime traveling to distant lands in search of a primitive paradise. Believing that the key to unleashing his creativity was to be found in faraway places not yet corrupted by civilization, he sojourned to ever more remote areas in Europe, the Caribbean, and Polynesia. “To do something new,” he said, “you have to go back to the origins, to humanity in its infancy.”1 But on arriving at each destination he discovered that the reality he encountered was very different from the paradise he had imagined. He had envisioned each new place as a sacred world where people lived simply, freely, and without inhibitions, but he instead found complex societies with their own difficult realities. He turned to his art to capture this elusive paradise, depicting an idealized, mythic dreamworld. Gauguin: Maker of Myth explores the ways the artist created myths over the course of his career. A self-proclaimed “teller of tales,” Gauguin knew the most potent myths were not wholesale fabrications but rather those that blended fact with fiction. He used this to his advantage, painting and sculpting works of art that make it difficult to discern where reality ended and where his imaginary world began. Personal Often spun from a kernel of truth, the fantastic myths Gauguin created fre- Myths quently concerned his personal identity. These biographical tales were a type of self-promotion, an attempt to establish his persona and artistic credibility. -

The Symbolism of Paul Gauguin

CHAPTER 1 Gauguin’s Heritage His Family and Their Nineteenth-Century World What I wish [to explore] is a still undiscovered corner of myself. To Emile Bernard, end of August 1889 Paul Gauguin’s paternal grandfather, Guillaume, and his uncle Isidore Gau- guin appear to have been small property owners in the region of Orléans. His father, Clovis, had been a political writer on the staff of the left-leaning, anti-Bonapartiste Le National before sailing for Peru in 1849, with his wife, Aline, their year-old son, Paul, and their daughter, Marie. He intended to found a newspaper in Peru, but he probably also left France in fear of reprisals from the leaders of the coup that brought Napoleon III to power. Clovis, who suffered from a heart ailment, never made it to Peru; he died on the way.1 The cultural background of Gauguin’s maternal side is much better doc- umented. His maternal grandfather, André Chazal, descended from a fam- ily of printers and was one of two artist brothers specializing in decorative designs; what little of his work has been identified reveals considerable dec- orative talent and technical skill.2 In 1821 he married one of the employees in his printing and lithography workshop, Flora Tristan y Moscoso (fig. 1), the illegitimate daughter of a Peruvian nobleman who resided in France with her French mother. The couple had considerable marital difficulties.[FIG 1] Flora left her husband and two children in 1825 and worked to support her- self. In 1830 she wrote her Peruvian uncle Don Pio Tristan y Moscoso to re- quest part of afamily inheritance.