Democracy, Less Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Chambers: Unicameral Or Bicameral?

Legislative Chambers: Unicameral or Bicameral? Legislative Chambers: Unicameral or Bicameral? How many chambers a parliament should have is a controversial question in constitutional law. Having two legislative chambers grew out of the monarchy system in the UK and other European countries, where there was a need to represent both the aristocracy and the common man, and out of the federal system in the US. where individual states required representation. In recent years, unicameral systems, or those with one legislative chamber, were associated with authoritarian states. Although that perception does not currently hold true, there appears to be a general trend toward two chambers in emerging democracies, particularly in larger countries. Given historical, cultural and political factors, governments must decide whether one-chamber or two chambers better serve the needs of the country. Bicameral Chambers A bicameral legislature is composed of two-chambers, usually termed the lower house and upper house. The lower house is usually based proportionally on population with each member representing the same number of citizens in each district or region. The upper house varies more broadly in the way in which members are selected, including inheritance, appointment by various bodies and direct and indirect elections. Representation in the upper house can reflect political subdivisions, as is the case for the US Senate, German Bundesrat and Indian Rajya Sabha. Bicameral systems tend to occur in federal states, because of that system’s two-tiered power structure. Where subdivisions are drawn to coincide with other important societal units, the upper house can serve to represent ethnic, religious or tribal groupings, as in India or Ethiopia. -

Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-Study*

brazilianpoliticalsciencereview ARTICLE Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-study* Marta Arretche University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil The article distinguishes federal states from bicameralism and mechanisms of territorial representation in order to examine the association of each with institutional change in 32 countries by using constitutional amendments as a proxy. It reveals that bicameralism tends to be a better predictor of constitutional stability than federalism. All of the bicameral cases that are associated with high rates of constitutional amendment are also federal states, including Brazil, India, Austria, and Malaysia. In order to explore the mechanisms explaining this unexpected outcome, the article also examines the voting behavior of Brazilian senators constitutional amendments proposals (CAPs). It shows that the Brazilian Senate is a partisan Chamber. The article concludes that regional influence over institutional change can be substantially reduced, even under symmetrical bicameralism in which the Senate acts as a second veto arena, when party discipline prevails over the cohesion of regional representation. Keywords: Federalism; Bicameralism; Senate; Institutional change; Brazil. well-established proposition in the institutional literature argues that federal Astates tend to take a slow reform path. Among other typical federal institutions, the second legislative body (the Senate) common to federal systems (Lijphart 1999; Stepan * The Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Estado -

House of Representatives 1437 1996 T82.18

1996 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES T82.18 Nussle Sanford Thomas So the motion to lay the resolution on D-day, the night before. It was Packard Saxton Thornberry Parker Scarborough Tiahrt on the table was agreed to. about my 200th speech. The gentleman Paxon Schaefer Torkildsen A motion to reconsider the vote from Wisconsin [Mr. GUNDERSON] has Peterson (MN) Schiff Traficant whereby said motion was agreed to made about seven, eight speeches in 16 Petri Seastrand Upton was, by unanimous consent, laid on the years. I am about to break 200 tonight, Pombo Sensenbrenner Vucanovich Porter Shadegg Walker table. I think, warning about the spread of Pryce Shaw Walsh T the world's greatest health problem, at Quillen Shays Wamp 82.18 POINT OF PERSONAL PRIVILEGE least in this country, particularly be- Quinn Shuster Watts (OK) Mr. DORNAN rose to a question of Radanovich Skeen Weldon (FL) cause it involves young men in the Ramstad Smith (MI) Weller personal privilege. prime of their lives. Regula Smith (NJ) White The SPEAKER pro tempore, Mr. ``This is from a young man dying of Riggs Smith (WA) Whitfield LAHOOD, pursuant to clause 1 of rule AIDS. His name is John R. Gail, Jr. He Roberts Solomon Wicker IX, recognized Mr. DORNAN for one Rogers Souder Wolf is from Centerville, OH. It says: hour. Rohrabacher Spence Young (AK) `Mr. Dornan, I caught your speech on Mr. DORNAN made the following Ros-Lehtinen Stearns Young (FL) AIDS yesterday over C±SPAN. I must Roth Stump Zeliff statement: Roukema Talent Zimmer ``Mr. Speaker, I will be showing no commend you. -

Grassroots Toolkit

Congratulations! If you are using this toolkit, it is likely that you are plunging (or have already plunged) into the whirlpool of political action. It is an exciting and sometimes scary undertaking, but its rewards will far outweigh the effort. You are a leader in the profession and your actions will help to protect the public we serve. We commend you for taking up this challenge, and provide this guide as one of the many tools available at the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) to help you. Athletic trainers are regulated in 49 states. As the profession has evolved, it has become critical that regulation becomes more standardized and is effective in all jurisdictions. The National Athletic Trainers’ Association benefits from the commitment and involvement of its members, and that dedication is evident in this legislative toolkit. It is truly an example of members making it happen. Thanks go to the entire NATA Governmental Affairs Committee and leadership. The NATA, through its Board of Directors, Governmental Affairs Committee, and staff stand ready to assist you. Please contact us for additional information or resources. Sincerely, Scott Sailor, ATC Jeff McKibbin, ATC Dave Saddler President GAC Chair Executive Director Lathan Watts Amy Callender Manager of State Government Affairs Director of Government Affairs Table of Contents SECTION PAGE # I. Government Relations State Legislatures 4 Terminology 4 Structure 5 Legislative Staff 6 II. How a Bill Becomes Law Bill Introduction 7 Sunrise & Sunset Review 7 Legislative Committees 8 Floor Action 9 Enactment 10 Process Flow Chart 11 III. Administrative Agency Regulations Lobbying Regulators 12 IV. -

Role and Functions of Upper House

COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATION ROLE AND FUNCTIONS OF UPPER HOUSE By Dr. Anant Kalse, Principal Secretary, Maharashtra Legislature Secretariat. Maharashtra Legislature Secretariat Vidhan Bhavan, Nagpur ROLE AND FUNCTIONS OF UPPER HOUSE By Dr. Anant Kalse, Principal Secretary, Maharashtra Legislature Secretariat. Hb 851–1 FOREWORD An attempt is made by this publication to present the position of the second chambers of Legislature in the Indian Parliamentary System and the world. It throws light on the role and necessity of bicameral system in our Parliamentary form of Government. The House of Elders, as is popularly known, takes a lead in reaffirming the core values of the republic and set up the highest standards of healthy debates and meaningful discussions in Parliamentary Democracy. The debate and discussion can be more free, more objective and more useful in the second chamber. Bicameralism is a fit instrument of federalism and it acts as a check to hasty, rash and ill-considered legislation by bringing sobriety of thought on measures passed by the Lower House. Due to over increasing volume of legislations in a modern State, it is extremely difficult for a single chamber to devote sufficient time and attention to every measure that comes before it. A second chamber naturally gives relief to the Lower House. I am extremely grateful to Hon. Shri Ramraje Naik-Nimbalkar, Chairman, Maharashtra Legislative Council, and Hon. Shri Haribhau Bagade, Speaker, Maharashtra Legislative Assembly for their continuous support and motivation in accomplishing this task. I am also grateful to Shri N. G. Kale, Deputy Secretary (Law), Shri B.B. Waghmare, Librarian, Information and Research Officer, Shri Nilesh Wadnerkar, Technical Assistant, Maharashtra Legislature Secretariat for rendering valuable assistance in compiling this publication. -

Members' Parliamentary Guide

Members’ Parliamentary Guide May 2019 Members’ Parliamentary Guide House of Assembly - Newfoundland & Labrador FEBRUARY 2021 This version is dated February 2021. For the most current version, visit: www.assembly.nl.ca/Members Members’ Parliamentary Guide February 2021 Members’ Guide to TableResources of Contents & Members’ Role in the House of Assembly ...................................... 1 Allowance Structures of Legislature ................................................................... 2 Standing Orders .............................................................................. 3 May 2019 General Assembly ........................................................................... 3 Session......................................................................................... 4 Sitting .......................................................................................... 4 Parliamentary Calendar .............................................................. 4 Daily Sittings ................................................................................ 5 Recess .......................................................................................... 5 Quorum ....................................................................................... 6 Adjournment (Sitting) ................................................................. 6 Prorogation ................................................................................. 6 Dissolution.................................................................................. -

Bicameralism

Bicameralism International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 2 Bicameralism International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 2 Elliot Bulmer © 2017 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Second edition First published in 2014 by International IDEA International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/> International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Telephone: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <http://www.idea.int> Cover design: International IDEA Cover illustration: © 123RF, <http://www.123rf.com> Produced using Booktype: <https://booktype.pro> ISBN: 978-91-7671-107-1 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 Advantages of bicameralism..................................................................................... -

Glossary of Legislative Terms

GLOSSARY OF LEGISLATIVE TERMS ABSENT -- Not present at a session. Absent with leave--not present at a session with consent. Absent without leave--not present at a session without consent. ACT -- Legislation enacted into law. A bill that has passed both houses of the legislature, been enrolled, ratified, signed by the governor or passed over the governor's office, and printed. It is a permanent measure, having the force of law until repealed. Local act -- Legislation enacted into law that has limited application. Private act -- Legislation enacted into law that has limited application. Public act -- Legislation enacted into law that applies to the public at large. ADHERE -- A step in parliamentary procedure whereby one house of the legislature votes to stand by its previous action in response to some conflicting action by the other chamber. ADJOURNMENT -- Termination of a session for that day, with the hour and day of the next meeting being set. ADJOURNMENT SINE DIE -- Final termination of a regular or special legislative session. ADOPTION -- Approval or acceptance; usually applied to amendments, committee reports or resolutions. AMENDMENT -- Any alteration made (or proposed to be made) to a bill or clause thereof, by adding, deleting, substituting, or omitting. Committee amendment -- an alteration made (or proposed to be made) to a bill that is offered by a legislative committee. Floor amendment -- an alternation offered to a legislative document that is presented by a legislator while that document is being discussed on the floor of that legislator's chamber. APPEAL -- A parliamentary procedure for testing (and possibly changing) the decision of a presiding officer. -

Europe: Fact Sheet on Parliamentary and Presidential Elections

Europe: Fact Sheet on Parliamentary and Presidential Elections July 30, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46858 Europe: Fact Sheet on Parliamentary and Presidential Elections Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 European Elections in 2021 ............................................................................................................. 2 European Parliamentary and Presidential Elections ........................................................................ 3 Figures Figure 1. European Elections Scheduled for 2021 .......................................................................... 3 Tables Table 1. European Parliamentary and Presidential Elections .......................................................... 3 Contacts Author Information .......................................................................................................................... 6 Europe: Fact Sheet on Parliamentary and Presidential Elections Introduction This report provides a map of parliamentary and presidential elections that have been held or are scheduled to hold at the national level in Europe in 2021, and a table of recent and upcoming parliamentary and presidential elections at the national level in Europe. It includes dates for direct elections only, and excludes indirect elections.1 Europe is defined in this product as the fifty countries under the portfolio of the U.S. Department -

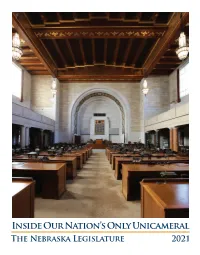

Inside Our Nation's Only Unicameral: The

Inside Our Nation’s Only Unicameral The Nebraska Legislature 2021 Origin of the Unicameral ebraska’s Legislature is unique among state Nlegislatures in the country because it consists of a single body of lawmakers—a one-house legislature, or unicameral. This was not always the case. Nebraska had a senate and a house of representatives for the first 68 years of the state’s existence. It took decades of work to convice Nebraskans to do away with “Every act of the legislature and every act of each individual the two-house system (see Norton excerpt, right). must be transacted in the spotlight of publicity,” Norris said. The potential cost-saving aspects of a unicameral In a one-house legislature, Norris said, no actions could be system helped the idea gain popularity during the Great concealed as too often happened in conference committees. Depression. A petition campaign led by the prestigious A conference committee reconciles differences in legislation U.S. Sen. George W. Norris benefited from two other when the two chambers of a bicameral legislature pass different popular proposals that also were on the ballot that year: versions of a bill. In Nebraska, the appointed six-member a local option on prohibition and legalized pari-mutuel betting. In 1934, Nebraska voters finally decided to reform committee met in secret, and members’ votes were not the state legislature on a 286,086 to 193,152 vote. public record. Norris said these committees had too Norris was a “New Deal Republican” from McCook. much power and easily could be influenced by lobbyists. -

A Second Chamber for the Scottish Parliament?

Edinburgh Research Explorer A Second Chamber for the Scottish Parliament? Citation for published version: MacQueen, H 2015, 'A Second Chamber for the Scottish Parliament?', Scottish Affairs, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 432-451. https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.2015.0095 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/scot.2015.0095 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Published In: Scottish Affairs General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 A SECOND CHAMBER FOR THE SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT? Hector L MacQueen* This paper is a revised and updated version of an earlier one1 prompted by an interview with the then Presiding Officer of the Scottish Parliament, Sir David Steel (now Lord Steel of Aikwood), published in The Scotsman on Boxing Day 2002. Sir David indicated that he had, “in the light of experience”, come to favour having a form of second chamber in the Scottish Parliament. He was quoted as follows: “There is an argument for saying, should we have further revision [of legislation]. -

Comparative Overview of Consultative Practices Within the Second Chambers of EU National Legislatures

Comparative overview of consultative practices within the second chambers of EU national legislatures This report was written by Pierre Schmitt (Leuven Centre for Global Governance Studies). The author thanks Dr. Axel Marx for his comments on a first draft of the report. It does not represent the official views of the Committee of the Regions. More information on the European Union and the Committee of the Regions is available online at http://www.europa.eu and http://www.cor.europa.eu respectively. Catalogue number: QG-05-14-008-EN-N ISBN: 978-92-895-0793-6 DOI: 10.2863/11493 © European Union, October 2014 Partial reproduction is allowed, provided that the source is explicitly mentioned. Table of Contents 1 Executive summary ........................................................................................... 1 2 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 5 3 Second chambers in the literature ................................................................. 11 3.1 Representation of different interests ........................................................... 13 3.2 The independence from the executive ........................................................ 16 3.3 The acting as a veto-player ......................................................................... 17 3.4 The performance of different parliamentary duties .................................... 18 4 Presentation of the second chambers within the national legislatures of EU Member States .........................................................................................