Using Petitions to Teach Slavery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eminist Frontiers and Gendered Negotiations : Women Who Shaped the Midwest / Edited by Yvonne Johnson

eminist FFrontiers WomenWho Shaped the Midwest Edited by Yvonne J. Johnson Truman State University Press Copyright © 2010 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri USA All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover images: Linda Warfel Slaughter (Courtesy of State Historical Society of North Dakota), Marietta Bones (Reproduced from American Women: Fifteen Hundred Biographies with over 1,400 Portraits), Carry Nation (Kansas Historical Society, Topeka), Esther Twente (Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas), Harriett Friedman Woods (Andrew Woods). Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Type: Minion Pro © Adobe Systems Inc., and Mistral © URW Printed by: Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Feminist frontiers and gendered negotiations : women who shaped the Midwest / edited by Yvonne Johnson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-935503-02-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Women political activists—Middle West—Biography. 2. Women civil rights workers— Middle West—Biography. 3. Women social reformers—Middle West—Biography. 4. Feminists—Middle West—Biography. 5. Women—Middle West—Biography. 6. Middle West—Biography. 7. Women in politics—Middle West—History. 8. Sex role—Middle West—History. 9. Middle West—Social conditions. 10. Middle West—Politics and government. I. Johnson, Yvonne, 1945– HQ1236.5.U6F45 2009 305.420977—dc22 2009040092 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. The paper in this publication meets or exceeds the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Mate- rials, ANSI Z39.48–1992. Contents Illustrations vi Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix Frances Dana Gage 1 “Turning the World Upside Down” Jeffrey E. -

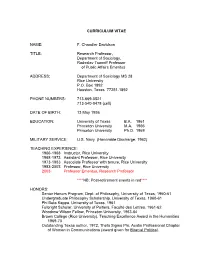

F. Chandler Davidson TITLE

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: F. Chandler Davidson TITLE: Research Professor, Department of Sociology, Radoslav Tsanoff Professor of Public Affairs Emeritus ADDRESS: Department of Sociology MS 28 Rice University P.O. Box 1892 Houston, Texas 77251-1892 PHONE NUMBERS: 713-669-0521 713-540-0478 (cell) DATE OF BIRTH: 13 May 1936 EDUCATION: University of Texas B.A. 1961 Princeton University M.A. 1966 Princeton University Ph.D. 1969 MILITARY SERVICE: U.S. Navy (Honorable Discharge, 1962) TEACHING EXPERIENCE: 1966-1968 Instructor, Rice University 1968-1973 Assistant Professor, Rice University 1973-1983 Associate Professor with tenure, Rice University 1983-2003 Professor, Rice University 2003- Professor Emeritus, Research Professor ****NB: Post-retirement events in red**** HONORS: Senior Honors Program, Dept. of Philosophy, University of Texas, 1960-61 Undergraduate Philosophy Scholarship, University of Texas, 1960-61 Phi Beta Kappa, University of Texas, 1961 Fulbright Scholar, University of Poitiers, Faculté des Lettres, 1961-62 Woodrow Wilson Fellow, Princeton University, 1963-64 Brown College (Rice University), Teaching Excellence Award in the Humanities 1969-70 Outstanding Texas author, 1972, Theta Sigma Phi, Austin Professional Chapter of Women in Communications (award given for Biracial Politics). Chandler Davidson Curriculum Vitae page 2 Research Fellow, National Endowment for the Humanities, 1976-77 Rice University Provost Lecturer, 1985 Controversies in Minority Voting, co-edited with Bernard Grofman, chosen as an Outstanding Book on Human Rights in the United States by the Gustavus Myers Center for the Study of Human Rights, 1993 Quiet Revolution in the South, co-edited with Bernard Grofman, chosen as the winner of the Richard F. Fenno Prize awarded annually by the Legislative Studies section of the American Political Science Association for the best book in legislative studies published in the previous year, 1995 Ally Award, Center for the Healing of Racism (Houston), 1996 George R. -

The American People

A01_NASH0008_08_SE_FM.indd Page 1 2/5/16 11:58 AM s-w-149 /205/PH02203/9780134170008_NASH/NASH_CREATING_A_NATION_AND_A_SOCIETY8_SE_97801341 ... THE AMERICAN PEOPLE Creating a Nation and a Society Volume 1 To 1877 EIGHTH EDITION RESALE Gary B. Nash Julie Roy Jeffrey University of California, Los Angeles Goucher College GENERAL EDITOR GENERAL EDITOR John R. Howe Allan M. Winkler University of MinnesotaFOR Miami University Allen F. Davis Charlene Mires Temple University Rutgers University—Camden Peter J. Frederick Carla Gardina Pestana NOTWabash College Miami University Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York City San Francisco Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montréal Toronto Delhi Mexico City São Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo A01_NASH0008_08_SE_FM.indd Page 2 2/5/16 11:58 AM s-w-149 /205/PH02203/9780134170008_NASH/NASH_CREATING_A_NATION_AND_A_SOCIETY8_SE_97801341 ... Editor-in-Chief: Ashley Dodge Managing Editor: Amber Mackey Program Manager: Carly Czech Production Managing Editor: Denise Forlow Production Project Manager: Manuel Echevarria Editorial Assistant (Program Support): Casseia Lewis Senior Marketing Coordinator: Susan Osterlitz Editorial Project Manager: Doug Bell, Lumina Datamatics, Inc. Development Editor: Jeffrey L. Goldings Asset Development Project Management: LearningMate Solutions, Ltd. Senior Operations Supervisor: Mary Fischer Operations Specialist: Mary Ann Gloriande Associate Director of Design: Blair Brown Interior Design: Kathryn Foot Cover Director: Maria Lange Cover Project Manager: Lumina Datamatics, Inc. Cover Image: Everett Historical/Shutterstock Full-Service Project Management and Composition: Jogender Taneja, iEnergizer Aptara®, Ltd. Printer/Binder: RR Donnelley/Willard Cover Printer: Phoenix Color/Hagerstown Acknowledgements of third party content appear on page C-1, which constitutes an extension of this copyright page. Copyright © 2017, 2011, 2008 by Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliates. -

Womens Responses to the Great Plains Landscape

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1988 "There is Some Splendid Scenery" Womens Responses to the Great Plains Landscape Julie Roy Jeffrey Goucher College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Jeffrey, Julie Roy, ""There is Some Splendid Scenery" Womens Responses to the Great Plains Landscape" (1988). Great Plains Quarterly. 376. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/376 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. "THERE IS SOME SPLENDID SCENERY" WOMEN'S RESPONSES TO THE GREAT PLAINS LANDSCAPE JULIE ROY JEFFREY During the decades of exploration and set noticed, some Americans seemed "insensible tlement of the trans-Mississippi West, travelers to the wonders of inanimate nature" because and emigrants encountered a new kind of "their eyes ... [are] fixed upon another sight landscape on the Great Plains. Aside from . draining swamps, turning the course of dramatic geological formations like Court rivers, peopling solitudes, and subduing na house Rock, this landscape lacked many of the ture. 1 visual qualities conventionally associated with Many women settlers between 1850 and natural beauty in the nineteenth century. "It 1900 saw the Great Plains in culturally predic may enchant the imagination for a moment to table ways, with attitudes ranging from indif look over the prairies and plains as far as the ference to romantic ecstasy. -

Century American History Graduate Reading List (1.31.13)

19 TH CENTURY AMERICAN HISTORY GRADUATE READING LIST (1.31.13) Overview The following reading list provides a general overview of the subjects and texts that students should study in preparing to write the nineteenth century portion of American and US Minor and Major exams. How to use the reading lists Like our PDR courses, our exam reading lists divide American history into three broad periods: The Colonial Era; the Nineteenth Century, and the Twentieth Century. Exam questions will likewise cover these three broad periods, although some questions may ask you to think across periods. Please use all three reading lists to develop your own personalized exam reading lists. Beginning well in advance of the planned exam date, you should develop, update and personalize your own reading lists to include any recently published works not yet on the departmental lists, as well as any texts you consider central to your own field. You can plan your exam reading by marking off texts that you have read and the texts you plan to read. You will not be expected to master all the books and articles on all three of the lists, but you should have some command of most of the subject areas. Once you have put together your own annotated and updated version of the lists you should meet with your examiners to discuss and review your personalized lists and reading plan. Such meetings should occur well in advance of your exam date and will allow you to confirm that your lists are up-to-date, and include a suitable selection of texts. -

2003 Memphis, TN

From the OAH President I am most pleased to welcome you to the ninety-sixth annual meeting of the Organization of American Historians. As a small learned society, founded nearly a century ago, our predecessor took its original name from the great river valley in which Memphis sits and took as its symbol the wonderful boats which once traversed the mighty river that still dominates the city. We have long since outgrown the name Mississippi Valley Historical Association, and we are no longer simply a learned society but an organization whose members are engaged as much in the pedagogy and presentation of history as its production. But Memphis and its environs with its Indian mounds and battlefields, its music and its museums, its conflicts over slavery, labor, and civil rights speaks broadly to the struggles for justice which is the theme of this year’s meeting. Photo by John T. Consoli Ira Berlin That theme gains special moment since the second full day of our meeting, Friday, 4 April, marks the thirty-fifth anniversary of the assassination of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel not far from where we are convening. OAH will be joining with the city of Memphis and a variety of civic associations, religious organizations, and labor unions to commemorate that historic moment. Our meeting will reflect upon that tragedy and the struggles that both preceded and followed the murder of Martin Luther King, along with a host of similar struggles as the people of the American colonies and the American republic labored to realize the ideals set forth in the nation’s founding charter. -

View the 2021 OAH Awards Program

OAH ANNUAL 2021 MEETING VIRTUAL CONFERENCE ON AMERICAN HISTORY PATHWAYS TO DEMOCRACY April 15–18, 2021 OAH AWARDS CEREMONY PROGRAM The Organization of American Historians thanks Oxford University Press for its continued financial support of the OAH Awards and its Clio Sponsorship of the OAH Annual Meeting. 2021 OAH AWARDS AND PRIZES OAH AWARDS AND PRIZES Roy Rosenzweig Distinguished Service Award .......................................................... 3 Friend of History Award ........................................................................................... 4 Frederick Jackson Turner Award ............................................................................... 6 Merle Curti Social History Award ............................................................................ 7 Liberty Legacy Foundation Award ............................................................................ 8 Merle Curti Intellectual History Award .................................................................. 10 Ray Allen Billington Prize ...................................................................................... 11 Civil War and Reconstruction Book Award ............................................................ 12 Darlene Clark Hine Award ..................................................................................... 13 Mary Nickliss Prize in U.S. Women’s and/or Gender History ................................. 14 James A. Rawley Prize ........................................................................................... -

The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society: Concise Edition, Volume 2 (8Th Edition) Online

g7JVN (Free pdf) The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society: Concise Edition, Volume 2 (8th Edition) Online [g7JVN.ebook] The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society: Concise Edition, Volume 2 (8th Edition) Pdf Free Gary B Nash, Julie Roy Jeffrey, John R. Howe, Allan M. Winkler, Allen F. Davis, Charlene Mires, Peter J. Frederick, Carla Gardina Pestana DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub #254912 in Books 2016-03-11Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 10.70 x .80 x 8.40l, .0 #File Name: 0134169999432 pages | File size: 18.Mb Gary B Nash, Julie Roy Jeffrey, John R. Howe, Allan M. Winkler, Allen F. Davis, Charlene Mires, Peter J. Frederick, Carla Gardina Pestana : The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society: Concise Edition, Volume 2 (8th Edition) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society: Concise Edition, Volume 2 (8th Edition): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Good ValueBy A. BuchananI loved being able to find this book in an actual book format and not loose leaf which was all my campus bookstore offered. That would have lasted 5 days with my kids around! =D Accurate content, and good price on .0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Just what my teacher requestedBy AshleyWas perfect for my class! Much better than buying it. Fast shipping. Great condition also0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Pretty good! I am satisfiedBy Anika TownsendThere was a little wrinkling of some of the pages, and it's obvious that its used, but it came in a timely manner, and is everything i need for the class i am taking.