Seed Sector Study of Southern Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Series Livelihood Baseline Analysis Baidoa-Urban

Technical Series Report No VI. 22 May 20, 2009 Livelihood Baseline Analysis Baidoa-Urban Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit - Somalia Box 1230, Village Market Nairobi, Kenya Tel: 254-20-4000000 Fax: 254-20-4000555 Website: www.fsnau.org Email: [email protected] Technical and Funding Agencies Managerial Support European Commission FSNAU Technical Series Report No VI. 18 ii Issued May 20, 2009 Acknowledgements This assessment would not have been possible without funding from the European Commission (EC) and the US Office of Foreign Disaster and Assistance (OFDA). FSAU would like to extend a special thanks to FEWS NET for their funding contributions and technical support, especially to Alex King, a consultant of the Food Economy Group (FEG) who lead the urban analysis. The study benefited from the contributions made by Mohamed Yusuf Aw-Dahir, the FEWS NET Representative to Somalia, and Sidow Ibrahim Addow, FEWS NET Market and Trade Advisor. FSAU would also like to extend a special thanks to Bay region and Baidoa local government authorities and agencies, the Baidoa Intellectual Association and the various other partner organizations and community members that provided information for the assessment. The fieldwork and analysis of this study would not have been possible without the leading baseline expertise and work of the two FSAU Senior Livelihood Analysts and the FSAU Livelihoods Baseline Team consisting of 7 analysts, who collected and analyzed the field data and who continue to work and deliver high quality outputs under very difficult conditions in Somalia. This team was lead by FSAU Lead Livelihood Baseline Livelihood Analyst, Abdi Hussein Roble, and Assistant Lead Livelihoods Baseline Analyst, Abdulaziz Moalin Aden, and the team of FSAU Field Analysts included, Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud, Abdirahaman Mohamed Yusuf, Yusuf Warsame Mire, Mohanoud Ibrahim Asser and Abdulbari Abdi sheikh. -

Reserve 2016 Direct Beneficiaries : Men Women Boys Girls Total 0 500 1

Requesting Organization : CARE Somalia Allocation Type : Reserve 2016 Primary Cluster Sub Cluster Percentage Nutrition 100.00 100 Project Title : Emergency Nutritional support for the Acutely malnourished drought affected population in Qardho and Bosaso Allocation Type Category : OPS Details Project Code : Fund Project Code : SOM-16/2470/R/Nut/INGO/2487 Cluster : Project Budget in US$ : 215,894.76 Planned project duration : 8 months Priority: Planned Start Date : 01/05/2016 Planned End Date : 31/12/2016 Actual Start Date: 01/05/2016 Actual End Date: 31/12/2016 Project Summary : This Project is designed to provide emergency nutrition assistance that matches immediate needs of drought affected women and children (boys and girls) < the age of 5 years in Bari region (Qardho and Bosaso) that are currently experiencing severe drought conditions. The project will prioritize the management of severe acute malnutrition and Infant and Young child Feeding (IYCF) and seeks to provide emergency nutrition assistance to 2500 boys and girls < the age of 5 years and 500 pregnant and lactating women in the drought affected communities in Bosaso and Qardho. Direct beneficiaries : Men Women Boys Girls Total 0 500 1,250 1,250 3,000 Other Beneficiaries : Beneficiary name Men Women Boys Girls Total Children under 5 0 0 1,250 1,250 2,500 Pregnant and Lactating Women 0 500 0 0 500 Indirect Beneficiaries : Catchment Population: 189,000 Link with allocation strategy : The project is designed to provide emergency nutrition support to women and children that are currently affected by the severe drought conditions. The proposed nutrition interventions will benefit a total of 2500 children < the age of 5 years and 500 Pregnant and lactating women who are acutely malnourished. -

COVID-19 Socio-Economic Impact Assessment

COVID-19 Socio-Economic Impact Assessment PUNTLAND The information contained in this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission but with acknowledgement of this publication as a source. Suggested citation: Puntland Statistics Department, Puntland State of Somalia. COVID-19 Socio-Economic Impact Assessment.. Additional information about the survey can be obtained from: Puntland Statistics Department, Ministry of Planning, Economic Development and International Cooperation, Puntland State of Somalia. Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.mopicplgov.net https://www.moh.pl.so http://www.pl.statistics.so Telephone no.: +252 906796747 or 00-252-5-843114 Social media: https://www.facebook.com/mopicpl https://www.facebook.com/ministryOfHealthPuntlamd/ https://twitter.com/PSD_MoPIC This report was produced by the Puntland State of Somalia, with support from the United Nations Population Fund, Somalia and key donors. COVID-19 Socio-Economic Impact Assessment PUNTLAND With technical support from: With financial contribution from: Puntland COVID-19 Report Foreword Today, Somalia and the world at large face severe Covid-19 pandemic crisis, coronavirus has no boundaries. It has severely affected the lives of people from different backgrounds. Across Somalia, disruptions of supply chains and closure of businesses has left workers without income, many of whom are vulnerable members in the society. The COVID-19 pandemic characterized by airports and border closures as well as lockdowns, is an economic and labour market shock, impacting not only supply but also demand. In Puntland, the implementation of lockdown measures has placed a major distress on the food value-chains, in particularly the international trade remittances from abroad and Small and Micro Enterprise Sector (SMEs) which are considered to be the main source of livelihoods for a greater part of the Somali population. -

Unicef Somalia

NUTRITION SURVEY REPORT BURHAKABA DISTRICT BAY REGION SOMALIA UNICEF SOUTH/CENTRAL ZONE OF SOMALIA BAIDOA OFFICE 2-15 JUNE 2000 Burhakaba District Nutrition Survey, June 2000 1. INTRODUCTION This nutrition survey is the ninth in a series of surveys agreed between UNICEF and FSAU throughout South and Central Somalia. UNICEF planned the surveys, conducted the fieldwork of data collection, trained enumerators, monitored survey activities, carried out data analysis and interpretation and paid the survey cost. UNICEF is grateful to World Vision and Burhakaba Health Authority who facilitated the work in Burhakaba District. 1.2 SURVEY JUSTIFICATION UNICEF supported a supplementary feeding programme in Burhakaba town in the last quarter of 1999 through Burhakaba Health Authority. UNICEF’s supplementary feeding support to Burhakaba was stopped in December 1999 due to misappropriation of supplies. Burhakaba district is situated on the frontline between RRA and SNA factions, is mainly dependent on agriculture and livestock and has suffered continuously from drought, security problems and lack of access to the main markets in Baidoa and Mogadishu during the past five years. Results from the Burhakaba town nutrition survey in September 1999 depicted the highest malnutrition rates in Bay region, with 28% global malnutrition. Although few humanitarian interventions have been possible in Burhakaba district that could improve the level of malnutrition, CARE International managed to continue to deliver food to all the main rural villages in the district, despite insecurity. The decision to conduct another nutrition survey in Burhakaba was made in order not only to compare the results with the previous data, but to obtain baseline data to assist in planning interventions by World Vision, which plans to start working in the district in July 2000. -

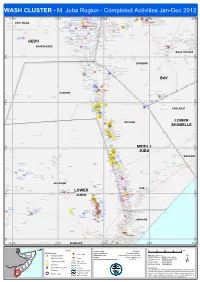

WASH Cluster (2012) ! Sustained Water Airstrip ! ! P ! ! ! Nominal Scale at A3 Paper Size: 1:820,000 All Admin

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

Report of the Tsunami Inter Agency Assessment Mission, Hafun to Gara

TSUNAMI INTER AGENCY ASSESSMENT MISSION Hafun to Gara’ad Northeast Somali Coastline th th Mission: 28 January to 8 February 2005 2 Table of Content Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 12 2.1 Description of the Tsunami.............................................................................................................. 12 2.2 Description of the Northeast coastline............................................................................................. 13 2.3 Seasonal calendar........................................................................................................................... 14 2.4 Governance structures .................................................................................................................... 15 2.5 Market prices ................................................................................................................................... 16 2.6 UN Agencies and NGOs (local and international) on ground.......................................................... 16 3. Methodology ............................................................................................................................................... 17 4. Food, Livelihood & Nutrition Security Sector......................................................................................... -

Peace in Puntland: Mapping the Progress Democratization, Decentralization, and Security and Rule of Law

Peace in Puntland: Mapping the Progress Democratization, Decentralization, and Security and Rule of Law Pillars of Peace Somali Programme Garowe, November 2015 Acknowledgment This Report was prepared by the Puntland Development Re- search Center (PDRC) and the Interpeace Regional Office for Eastern and Central Africa. Lead Researchers Research Coordinator: Ali Farah Ali Security and Rule of Law Pillar: Ahmed Osman Adan Democratization Pillar: Mohamoud Ali Said, Hassan Aden Mo- hamed Decentralization Pillar: Amina Mohamed Abdulkadir Audio and Video Unit: Muctar Mohamed Hersi Research Advisor Abdirahman Osman Raghe Editorial Support Peter W. Mackenzie, Peter Nordstrom, Jessamy Garver- Affeldt, Jesse Kariuki and Claire Elder Design and Layout David Müller Printer Kul Graphics Ltd Front cover photo: Swearing-in of Galkayo Local Council. Back cover photo: Mother of slain victim reaffirms her com- mittment to peace and rejection of revenge killings at MAVU film forum in Herojalle. ISBN: 978-9966-1665-7-9 Copyright: Puntland Development Research Center (PDRC) Published: November 2015 This report was produced by the Puntland Development Re- search Center (PDRC) with the support of Interpeace and represents exclusively their own views. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the contribut- ing donors and should not be relied upon as a statement of the contributing donors or their services. The contributing donors do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor do they accept responsibility for any use -

Somalia Humanitarian Fund 2017 Annual Report

2017 IN REVIEW: 1 SOMALIA HUMANITARIAN FUND 2 THE SHF THANKS ITS DONORS FOR THEIR GENEROUS SUPPORT IN 2017 CREDITS This document was produced by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Somalia. OCHA Somalia wishes to acknowledge the contributions of its committed staff at headquarters and in the field in preparing this document, as well as the SHF implementing partners, cluster coordinators and cluster support staff. The latest version of this document is available on the SHF website at www.unocha.org/somalia/shf. Full project details, financial updates, real-time allocation data and indicator achievements against targets are available at gms.unocha.org/bi. All data correct as of 20 April 2018. For additional information, please contact: Somalia Humanitarian Fund [email protected] | [email protected] Tel: +254 (0) 73 23 910 43 Front Cover An Internally Displaced Person (IDP) draws water from a shallow well rehabilitated by ACTED at Dalxiiska IDP camp, at the outskirts of Kismayo town, Somalia. Credit: ACTED The designations employed and the presentation of material on this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Financial data is provisional and may vary upon certification. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 FOREWORD 6 2017 IN REVIEW 7 AT A GLANCE 8 HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT 10 ABOUT SOMALIA -

Enhanced Enrolment of Pastoralists in the Implementation and Evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia

Enhanced enrolment of pastoralists in the implementation and evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia Prepared for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) by Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute UNICEF ESARO JUNE 2013 Enhanced enrolment of pastoralists in the implementation and evaluation of UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia © United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Nairobi, 2013 UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) PO Box 44145-00100 GPO Nairobi June 2013 The report was prepared for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) by Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the policies or the views of UNICEF. The text has not been edited to official publication standards and UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this publication do not imply an opinion on legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. For further information, please contact: Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, University of Basel: [email protected] Eugenie Reidy, UNICEF ESARO: [email protected] Dorothee Klaus, UNICEF ESARO: [email protected] Cover photograph © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-2301/Kate Holt 2 Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Middle Juba Region ,Sakow District

SOCIETY DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE ORGANIZATION (SDIO ) Email. Address [email protected],[email protected] Telephone +254700687528 Kenya +252-618222825 Somalia Liaison Office P.O.BOX 71537 – 00610 Nairobi, Kenya Headquarter Southern Somalia .Middle Juba region ,Sakow District Main Office Bay Region, Bay District Sub. Offices Qansah.Dhere and Diinsoor District Bay Region. All Middle Juba Districts and villages compiled list updating for old villages and new villages in our region 30 th December 2015 MIDDLE JUBA REGION Introduction Generally the middle Juba is more stable than other region like lower Juba. Middle Juba falls on the south west of Somalia, The region border lower Juba, Gedo, Bay and lower Shabelle. The region consists of four districts namely: 1. Bu'aale (The regional Capital) 2. Jilib 3. Sakow (is the larges district in the region) 4. Salagle DESCRIPTION OF THE COMMUNITY The community living in these region is predominantly Agro-pastoralist who mainly depend on rain fed crop and livestock production. The main crops are 'Maize, cowpea, and Sesame which are planted both 'Gu and Deyr' seasons these region also famous in livestock rearing especially cattle and shoats, but due to prolonged dry spells and intense conflicts, the economical situation of these communities has drastically deteriorated. Consequently many shocks such as, the ban of livestock in Garissa market and the recurrent closure of Kenya Somalia border (Which is the main market route) has grounded their hopes. Therefore Middle Juba has the largest farmland on both side of Juba River .those community living for that area most of them they produce a different products from local farmer, most of riverbank area living a Somalia Bantus, those communities is a backbone of Middle/lower Juba , because they are low cheap price of labour , example if you want a build Somali house , the one who is building is one of Somalia Bantus, Wilding ,Machining, etc . -

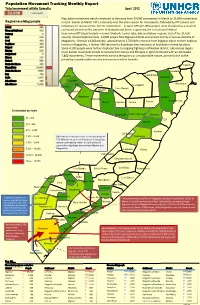

Population Movement Tracking Monthly Report

Population Movement Tracking Monthly Report Total movement within Somalia April 2012 33,000 nationwide Population movement trends continued to decrease from 39,000 movements in March to 33,000 movements Region receiving people in April. Similar to March 2012, insecurity was the main reason for movements, followed by IDP returns and Region People Awdal 400 temporary or seasonal cross border movements. In April, 65% (21,000 people) were displaced as a result of Woqooyi Galbeed 500 continued armed conflict between Al Shabaab and forces supporting the Transitional Federal Sanaag 0 Government(TFG) particularly in Lower Shabelle, Lower Juba, Bay and Bakool regions. Out of the 21,000 Bari 200 security related displacements, 14,000 people fled Afgooye district and arrived mainly in various districts of Sool 400 Mogadishu. Of these 14,000 people, approximately 3,700 IDPs returned from Afgooye closer to their habitual Togdheer 100 homes in Mogadishu, a further 590 returned to Baydhaba after cessation of hostilities in these locations. Nugaal 400 Some 4,100 people were further displaced due to ongoing fighting in Afmadow district, Juba Hoose region. Mudug 500 Cross border movement trends to Somalia from Kenya and Ethiopia in April continued with an estimated Galgaduud 0 2,800 movements. These movements are of a temporary or unsustainable nature, primarily due to the Hiraan 200 Bakool 400 prevailing unpredictable security environment within Somalia. Shabelle Dhexe 300 Caluula Mogadishu 20,000 Shabelle Hoose 1,000 Qandala Bay 700 Zeylac Laasqoray Gedo 3,200 Bossaso Juba Dhexe 100 Lughaye Iskushuban Juba Hoose 5,300 Baki Ceerigaabo Borama Berbera Ceel Afweyn Sheikh Gebiley Hargeysa Qardho Odweyne Bandarbeyla Burco Caynabo Xudun Taleex Estimated arrivals Buuhoodle Laas Caanood Garoowe 30 - 250 Eyl Burtinle 251 - 500 501 - 1,000 Jariiban Goldogob 1,001 - 2,500 IDPs who were displaced due to tensions between Gaalkacyo TFG-Allied forces and the Al Shabaab in Baydhaba 2,501 - 5,000 district continued to return. -

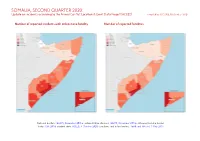

SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020

SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Ethiopia/Somalia border status: CIA, 2014; incident data: ACLED, 3 October 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 327 152 465 Conflict incidents by category 2 Violence against civilians 146 100 144 Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 2 Explosions / Remote 133 59 187 violence Methodology 3 Protests 28 1 1 Conflict incidents per province 4 Strategic developments 18 2 2 Riots 6 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 658 314 799 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). 2 SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known.