Sumerian Origins and Racial Characteristics. by PROFESSOR S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early History of Syria and Palestine

THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON Gbe Semitic Series THE EARLY HISTORY OF SYRIA AND PALESTINE By LEWIS BAYLES PATON : SERIES OF HAND-BOOKS IN SEM1T1CS EDITED BY JAMES ALEXANDER CRAIG PROFESSOR OF SEMITIC LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES AND HELLENISTIC GREEK, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Recent scientific research has stimulated an increasing interest in Semitic studies among scholars, students, and the serious read- ing public generally. It has provided us with a picture of a hitherto unknown civilization, and a history of one of the great branches of the human family. The object of the present Series is to state its results in popu- larly scientific form. Each work is complete in itself, and the Series, taken as a whole, neglects no phase of the general subject. Each contributor is a specialist in the subject assigned him, and has been chosen from the body of eminent Semitic scholars both in Europe and in this country. The Series will be composed of the following volumes I. Hebrews. History and Government. By Professor J. F. McCurdy, University of Toronto, Canada. II. Hebrews. Ethics arid Religion. By Professor Archibald Duff, Airedale College, Bradford, England. [/« Press. III. Hebrews. The Social Lije. By the Rev. Edward Day, Springfield, Mass. [No7i> Ready. IV. Babylonians and Assyrians, with introductory chapter on the Sumerians. History to the Fall of Babylon. V. Babylonians and Assyrians. Religion. By Professor J. A. Craig, University of Michigan. VI. Babylonians and Assyrians. Life and Customs. By Professor A. H. Sayce, University of Oxford, England. \Noiv Ready. VII. Babylonians and Assyrians. -

Intercultural Relations Between Southern Iran and the Oxus Civilization

Intercultural Relations between Southern Iran and the Oxus Civilization. The Strange Case of Bifacial Seal NMI 1660 Enrico Ascalone* University of Salento, Lecce, Italy (Received: 05 /05 /2013 ; Received in Revised form: 10 /09 /2013 ; Accepted: 02 /12 /2013 ) New archaeological evidences of the so-called “Bactrian-Margiana Archaeological Complex” (= BMAC) has invited a change in our knowledge of the cultural relations between Oxus civilization and south-eastern Iran during the III-II millennium B.C. transition period. The new archaeological projects in southern and western Turkmenistan, as well as attested at Gonur Depe, have showed a wider and more articulated relation in Asia Media, not only constrained to the movement of the Central Asian Bronze Age onto the Iranian plateau, Baluchistan, and western coast of the Persian Gulf. At the same time new research and excavations in the Jiroft valley has demonstrated a new cultural horizon in the eastern Iran. In this perspective, the new information from the Oxus (Bactria and Margiana) and Jiroft civilizations invite new interpretations on III-II millennium historical relations among eastern areas. In particular, it is possible to recognize south-eastern Iranian objects or influenced materials by Jiroft civilization in the Bactrian-Margiana archaeological complex. For these reasons the characteristic finds of BMAC recovered in Iran from Susa, Shahdad, Shahr-i Sokhta, Tepe Hissar, Khurab and Tepe Yahya have to be analyzed as part of a wider network and not simply explained with the movement of people from Central Asia towards southern Iran. An unpublished bifacial seal, now placed in the Bastan Museum, is an important line of evidence for a reassessment of the historical relations between two civilizations, representing a conceptual and ideological creation originated by the union of southern Iran and Central Asian cultural developments. -

The Development of Royal Insignia in Early Mesopotamia

The Development of Royal Insignia in Early Mesopotamia Bill McGrath 998581618 NMC 1424 Prof. Clemens Reichel Dec. 14th 2013 Table of Contents: 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Introductory Concerns: The AGA-circlet and the MEN-crown 2.0 The “Man in the Net-skirt” as Divinity 2.1 The “Man in the Net-skirt” as Ruler 2.2 Discussion and Possible Impacts of the Uruk Period Iconography 3.0 Royal Iconography in the ED period: Introduction 3.1 Royal Iconography in the ED Period: Transitionary Pieces 3.2 Royal Iconography in the ED period: Inscribed Royal Statuary 3.3 Royal Iconography in the ED period: Plaques and Wall-Plaques 3.4 Royal Iconography in the ED period: The Stele of Vultures and its Missing Insignia 4.0 Conclusions The Development of Royal Insignia in Early Mesopotamia 1.0 Introduction: The image of the earliest kings of ancient Mesopotamia is one obscured not only by the sands of time, but by the complexities of early multi-ethnic societies which were the first to undergo the transition from pre-urban tribalism to the early urbanism of the Uruk period, to the warring city-states of the Early Dynastic period and on. Playing a pivotal role in all of this were these early rulers whose elusive image, wherever identifiable, is of paramount importance to the study of the development and emergence of early civilization itself. In terms of the available media, foundation figurines, stelae and rock reliefs were reserved for royal deeds and offer some of the most unequivocal images of the early ruler. -

An Old Babylonian Cylinder Seal from Daskyleion in Northwestern Anatolia

ANES 42 (2005) 299-311 An Old Babylonian Cylinder Seal from Daskyleion in northwestern Anatolia Serap YAYLALI Adnan Menderes Üniversitesi Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi Arkeoloji Bölümü 09010 Aydın TURKEY Fax: +90 256 2135379 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This essay describes an Old Babylonian cylinder seal recovered coincidentally from a Byzantine deposit at the site of Daskyleion in northwestern Anatolia. The fi gurative scene and the cuneiform inscription carved on this seal is described in detail to place this artifact in its cultural and temporal context. This seal dating to a period between the late nineteenth and early eighteenth century B.C. depicts a protector goddess/Lama in a position paying respect to the god Adad. The rea- sons for the arrival of this seal in such a distant location far from its homeland is also evaluated in relation to the events that occurred between Anatolian and Mesopotamian cultures. It is proposed that this seal was a heirloom from the previous millennium that was brought to Daskyleion during the establishment of the Persian Satrapy at the site. Daskyleion, identifi ed with the city mound called Hisartepe on the southeastern of the Lake Manyas/Ku≥ (Daskylitis) near Ergili to the 30 km south of the town of Bandırma, in northwestern Turkey (Fig. 1), was the residence of the Persian satrap of the Hellespont and Phrygia. Archaeological excavations carried out in 1988 in the Byzantine deposits at Daskyleion surprisingly yielded two cylinder seals. One of them is Old Babylonian in date, whereas the other one is Neo-Babylonian in date.1 The Old Babylonian 1 Bakır 1991, p. -

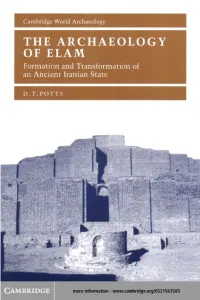

The Archaeology of Elam Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State

This page intentionally left blank The Archaeology of Elam Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State From the middle of the third millennium bc until the coming of Cyrus the Great, southwestern Iran was referred to in Mesopotamian sources as the land of Elam. A heterogenous collection of regions, Elam was home to a variety of groups, alternately the object of Mesopotamian aggres- sion, and aggressors themselves; an ethnic group seemingly swallowed up by the vast Achaemenid Persian empire, yet a force strong enough to attack Babylonia in the last centuries bc. The Elamite language is attested as late as the Medieval era, and the name Elam as late as 1300 in the records of the Nestorian church. This book examines the formation and transforma- tion of Elam’s many identities through both archaeological and written evidence, and brings to life one of the most important regions of Western Asia, re-evaluates its significance, and places it in the context of the most recent archaeological and historical scholarship. d. t. potts is Edwin Cuthbert Hall Professor in Middle Eastern Archaeology at the University of Sydney. He is the author of The Arabian Gulf in Antiquity, 2 vols. (1990), Mesopotamian Civilization (1997), and numerous articles in scholarly journals. cambridge world archaeology Series editor NORMAN YOFFEE, University of Michigan Editorial board SUSAN ALCOCK, University of Michigan TOM DILLEHAY, University of Kentucky CHRIS GOSDEN, University of Oxford CARLA SINOPOLI, University of Michigan The Cambridge World Archaeology series is addressed to students and professional archaeologists, and to academics in related disciplines. Each volume presents a survey of the archaeology of a region of the world, pro- viding an up-to-date account of research and integrating recent findings with new concerns of interpretation. -

Mesopotamian Himri

Mesopotamian himri Carasobarbus luteus â” Overview. Mesopotamian Himri learn more about names for this taxon. Add to a collection. Overview. Mesopotamia is a historical region in Western Asia situated within the Tigrisâ“Euphrates river system, in modern days roughly corresponding to most of Iraq, Kuwait, parts of Northern Saudi Arabia, the eastern parts of Syria, Southeastern Turkey, and regions along the Turkishâ“Syrian and Iranâ“Iraq borders. The Sumerians and Akkadians (including Assyrians and Babylonians) dominated Mesopotamia from the beginning of written history (c. 3100 BC) to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC, when it was conquered by the Mesopotamian art and architecture, the art and architecture of the ancient Mesopotamian civilizations. The name Mesopotamia has been used with varying connotations by ancient writers. Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, Sumeria, wearing a traditional kaunakes, limestone relief, c. 2500 bce; in the Louvre, Paris. © Photos.com/Jupiterimages. It has been thought that the rarity of stone in Mesopotamia contributed to the primary stylistic distinction between Sumerian and Egyptian sculpture. Ancient Mesopotamian Architecture. Major Monuments in Mesopotamian Art. Temples. Palaces. Walls. Tombs. Ceramics in Mesopotamian Art. Mesopotamian Metallurgy. Mesopotamian Sculpture. Painting in Mesopotamian Art. Characteristics of paintings. The lowlands of Mesopotamia cover a fertile plain, but its inhabitants had to face the dangers of invasions, extreme weather, droughts, and wild animal attacks. Their art reflects both their adaptation to and fear of these natural forces, as well as their military conquests. Go to new website Home » Carasobarbus luteus (Mesopotamian himri). Carasobarbus luteus. Scope: Global. Common Name(s): English. -

IMAGES of POWER: ANCIENT NEAR EAST: FOCUS (Sumerian Art and Architecture)

IMAGES OF POWER: ANCIENT NEAR EAST: FOCUS (Sumerian Art and Architecture) TITLE or DESIGNATION: White Temple and its Ziggurat CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Ancient Sumerian DATE: c. 3500-3000 B.C.E. LOCATION: Uruk (modern Warka, Iraq) ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: https://www.khanacademy.org/test- prep/ap-art-history/ancient- mediterranean-AP/ancient-near-east- AP/v/standing-male-worshipper TITLE or DESIGNATION: Statues of Votive Figures, from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar) CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Ancient Sumerian DATE: c. 2700 B.C.E. MEDIUM: gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://smarthistory.kha nacademy.org/the- standard-of-ur.html TITLE or DESIGNATION: Standard of Ur from the Royal Tombs at Ur CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Ancient Sumerian DATE: c. 2600-2400 B.C.E. MEDIUM: wood inlaid with shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone IMAGES OF POWER: ANCIENT NEAR EAST: SELECTED TEXT (Sumerian Art and Architecture) SUMERIAN ZIGGURATS Online Links: Ziggurat - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Architecture of Mesopotamia - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sumer - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Uruk - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Ziggurat of Ur - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Ziggurat of Ur – Smarthistory Sumerian Art - Smarthistory Iraq- The Cradle of Civilization - Michael Wood on YouTube ART of the ANCIENT NEAR EAST Online Links: Architecture of Mesopotamia - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sumer - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Standard of Ur - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia sumerianshakespeare.com The Standard of Ur - Smarthistory (video) Mesopotamia – YouTube Standard of Ur - Iraq's Archeological Past - Penn Museum Mesopotamian Masterpieces - Smithsonian Magazine White Temple and Ziggurat at Uruk, c. -

Download The

FROM ACCOUNTING TO WRITING The world’s first writing – cuneiform – (fig. 1) traces its beginnings back to an ancient system of accounting. This method of accounting used small geometrically shaped clay tokens to keep track of goods such as livestock and grain produced in the early farming communities of the ancient Near East. Writing, however, did not spring full blown from clay tokens. Surprisingly, it took the Mesopotamian belief in an afterlife to transform a dry and dusty accounting system into what we recognize as writing. Fig. 1. Clay tablet written in the cuneiform Script. Courtesy Denise Schmandt-Besserat. The Mesopotamians believed that to secure eternal life their names had to be kept alive by being spoken after their death. To insure the eternal vitality of their names and their ghosts, the Mesopotamians repurposed the old accounting symbols into phonetic signs “spelling” out a person’s name. Individuals’ names were inscribed on funerary offerings and served, in effect, as perpetual utterances of a name. Over time, the phonetic name inscriptions evolved into phonetic sentences appealing to the gods for eternal life. These impassioned supplications were the final stage of transition from the clay tokens of old into the first writing. BEFORE WRITING: ACCOUNTING WITH TOKENS – CA. 7500-3350 BC Early farmers of the Near East invented a system of small tokens to count and account for the goods they produced. (fig. 2) The token shapes represented various kinds of merchandise prevalent in the farming economy of the time. For example, a cone stood for a small measure of barley, a sphere for a larger measure of barley and a disc for sheep. -

Mesopotamia: the World's Earliest Civilization

Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2011 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition Kathleen Kuiper: Manager, Arts and Culture Rosen Educational Services Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor Nelson Sá: Art Director Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager Matthew Cauli: Designer, Cover Design Introduction by Dan Faust Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mesopotamia : the world's earliest civilization / edited by Kathleen Kuiper.—1st ed. p. cm.—(The Britannica guide to ancient civilizations) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61530-208- 6 (eBook) 1. Iraq—Civilization—To 634. I. Kuiper, Kathleen. DS71.M55 2010 935—dc22 2009053644 On the cover: The reconstructed Ishtar Gate, an enormous burnt-brick entryway located over the main thoroughfare in the ancient city of Babylon. Ishtar is the goddess of war and sexual love in the Sumerian tradition. Nico Tondini/Robert Harding World Imagery/ Getty Images Pp. -

The Babylonian World �

THE BABYLONIAN WORLD ᇹᇺᇹ As the layers of the foundations of modern science and mathematics and the builders of a towering, monumental urban city, the Babylonians were by far the most insistent people of the ancient world in addressing an audience beyond their time. This lavishly illustrated volume reflects the modernity of this advanced and prescient civilization with thirty-eight brand new essays from leading international scholars who view this world power of the Ancient Near East with a fresh and contemporary lens. Drawing from the growing database of cuneiform tablets, epigraphic research, and the most recent archaeological advances in the field, Gwendolyn Leick’s collection serves as the definitive reference resource as well as an introductory text for university students. By bringing into focus areas of concern typical for our own time – such as ecology, urbanism, power relations, plurality and complexity – this essential volume offers a variety of perspectives on certain key topics to reflect the current academic approaches and focus. These shifting viewpoints and diverse angles onto the ‘Babylonian World’ result in a truly kaleidoscopic view which reveals patterns and bright fragments of this ‘lost world’ in unexpected ways. From discussions of agriculture and rural life to the astonishing walled city of Babylon with its massive ramparts and towering ziggurats, from Babylonian fashion and material culture to its spiritual world, indivisible from that of the everyday, The Babylonian World is a sweeping and ambitious survey for students and specialists of this great civilization. Gwendolyn Leick is presently senior lecturer at Chelsea College of Art and Design. A specialist in the Ancient Near East, she has published extensively on the topic, including The Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Architecture and Who’s Who in the Ancient Near East. -

Great Khorasan Road) During the Third Millennium BC and the ”Dark Stone” Artefacts H.-P

The Grand’Route of Khorasan (Great Khorasan Road) during the third millennium BC and the ”dark stone” artefacts H.-P. Francfort To cite this version: H.-P. Francfort. The Grand’Route of Khorasan (Great Khorasan Road) during the third millennium BC and the ”dark stone” artefacts. Jan-Waalke Meyer; Emmanuelle Vila; Marjan Mashkour; Michèle Casanova; Régis Vallet. The Iranian Plateau during the Bronze Age. Development of urbanisation, production and trade, 1, MOM Editions, pp.247-266, 2019, Archéologies, 978-2-35668-063-1. halshs- 03059953 HAL Id: halshs-03059953 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03059953 Submitted on 14 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ARCHÉOLOGIE(S) // 1 ARCH. 1 THE IRANIAN PLATEAU DURING THE BRONZE AGE DEVELOPMENT OF URBANISATION, PRODUCTION AND TRADE edited by Jan-Waalke Meyer, Emmanuelle Vila, Marjan Mashkour, Michèle Casanova and Régis Vallet THE IRANIAN PLATEAU DURING THE BRONZE AGE. DEVELOPMENT OF URBANISATION, PRODUCTION AND TRADE AND PRODUCTION URBANISATION, OF DEVELOPMENT AGE. BRONZE THE IRANIAN DURING THE PLATEAU THE IRANIAN PLATEAU DURING THE BRONZE AGE. DEVELOPMENT OF URBANISATION, PRODUCTION AND TRADE ARCH. ARCHÉOLOGIE(S) // 1 The book compiles a portion of the contributions presenteD During the symposium “Urbanisation, commerce, subsistence and 1 production during the third millennium BC on the Iranian Plateau”, which took place at the Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée in Lyon, the 29-30 of April, 2014. -

Volume 44 (1940) Index

AMERICANJOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY MO ojVI MEN ( RVM TA PRIO RV ?INCo~b THE JOURNAL OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICALINSTITUTE OF AMERICA PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY THE INSTITUTE VOLUME XLIV 1940 Printed by The Rumford Press, Concord, N. H. EDITORIAL BOARD MARY HAMILTON SWINDLER, Bryn Mawr College, Editor-in-Chief STEPHEN B. LUCE, Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Mass., Editor, News and Discussions EDITH HALL DOHAN, University Museum, Philadelphia, Editor, Book Reviews ADVISORY BOARD OF ASSOCIATE EDITORS GEORGE A. BARTON, University of Pennsylvania (Oriental) CARL W. BLEGEN, University of Cincinnati (Aegean) LACEY D. CASKEY, Boston Museum of Fine Arts (GreekArchaeology: Vase Painting) GEORGE H. CHASE, Harvard University (American School at Athens) WILLIAM B. DINSMOOR, Columbia University (GreekArchaeology: Architecture) GEORGE W. ELDERKIN, Princeton University (Editor, 1924-1931) HETTY GOLDMAN, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N. J. (New Excavationsand Discoveries) BENJAMIN D. MERITT, Institute for Advanced Study (Epigraphy) CHARLES RUFUS MOREY, Princeton University (Mediaeval) EDWARD T. NEWELL, Numismatic Society, New York (Numismatics) GISELA M. A. RICHTER, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (GreekArchaeology: Sculpture) DAVID M. ROBINSON, Johns Hopkins University (Bibliography, General) MICHAEL I. ROSTOVTZEFF, Yale University (Roman) ALFRED TOZZER, Harvard University (American Archaeology) CAROLINE RANSOM WILLIAMS, Toledo, Ohio (Egyptian Archaeology) HONORARY EDITORS WILLIAM B. DINSMOOR, Columbia University (President of the Institute) LOUIS E. LORD, Oberlin College (Chairman of the Managing Committeeof the School at Athens) MILLAR BURROWS, Yale University (President of the American Schools of Oriental Research) ARCHAEOLOGICALNEWS AND DISCUSSIONS ADVISORY BOARD Egypt - Dows DUNHAM, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Orient. Western Asia-WILLIAM F. ALBRIGHT, Johns Hopkins University Far East --BENJAMIN ROWLAND,Fogg Museum of Art, Harvard University Greece.