II Diplomacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem Newsletter

NEWSLETTER The Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem June 2009 Pentecost Celebration Brings More than 800 Anglicans to Jerusalem An overflowing crowd of more than 800 parishioners from across Israel and Palestine filled the Cathedral of St. George the Martyr in Jerusalem to celebrate the Pentecost with a joyous birthday service led by Bishop Suheil Dawani. “We give thanks to God the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who was gathered us here this morning as one family from across the Diocese for the birthday of the one Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church,” said the Bishop in his sermon. “We are witnesses to our Lord’s death and His resurrection here in Jerusalem, the City of Peace, the City of the Resurrection and of a new covenant.” Children and adults, men, women, couples, grandparents, uncles and aunts, nieces and nephews, friends and colleagues, left their communities very early Sunday morning and rode tour buses to Jerusalem for the 10:30 a.m. joint Arabic and English Eucharist. The congregation packed the Cathedral’s nave into the north and south transepts, the three chapels, the Baptistery, and the Cathedral choir to welcome the coming of the Holy Spirit with hymn and prayers. “No longer are we strangers,” noted Bishop Suheil in his sermon. “No longer do we feel left out of our homes, our church, or our society. We belong to a re-born community that welcomes the stranger and the homeless, heals the sick, gives strength to the weak, upholds the oppressed, comforts the brokenhearted and gives witness to the love of God in the example of Jesus Christ.” The Bishop spoke of the many diocesan institutions that follow Christ’s example by providing compassion, healing and teaching for those in need. -

In the Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem 22 February 2017 Re

In the Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem 22nd February 2017 Re-dedication of St Saviour’s, Acre (Akko), Northern Israel. The Diocese of Jerusalem this week celebrates God’s goodness and marvels at the work of the Holy Spirit. For, on 21st February 2017 the Anglican Archbishop in Jerusalem, the Most Reverend Suheil Dawani, re-dedicated St Saviour’s Church in Acre. He did so in the presence of c.700 people, including the Greek Patriarch, His Beatitude Theophilos III; the Bishop of the Maronite Church in the Holy Land, the Right Reverend Musa Haj; the Imam of Al-Jazzar Mosque, Samir Asie; and representatives from the Muslim, Jewish and Christian communities, as well as individuals who had longed for the re-opening and reviving of this church since the majority of its congregation concerned about their security situation left Acre in 1948. Acre is an extraordinary corner of the Holy Land, with one of the best natural harbours in the region. Acre has been a prominent city since it was mentioned in the tribute list of Pharaoh Thutmose III in 16th century BCE. And before its capture by the crusaders in 1104, it had been held by the Egyptians, the Phoenicians, Persians, the Greeks and the Ummayads. St Paul visited it (cf. Acts 21.7), referring to it as Ptolemais and within 150 years it had a bishop. Acre became the port where pilgrims disembarked. The Crusaders built a complex fort with tunnels, churches and hospitals. It was captured by the Muslim commander Saladin and re-taken by Richard-the-Lion-Heart, before being re-captured by the Mamelukes, the Ottomans, the Egyptians, the Turks, and the British. -

August Newsletter 2012.Pdf

NEWSLETTER The Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem August 2012 Peace to you in the name of the Lord Greetings from Bishop Suheil Dawani Dear Friends, August has been a busy month throughout the Diocese. Summer Camps have been held in Nazareth and Jordan with over 400 youth attending. We have also received visitors from around the world in Jerusalem, and also from Germany and England in Jordan. For the 5th consecutive year we shared the ‘breaking of the fast’, Iftar, with our Muslim brothers at St. George’s Guest House. I also traveled to Jordan to attend their fast breaking meal of Ramadan, held by the king of Jordan, His Majesty King Abdullah Eben Al Hussien. We celebrated a number of confirmations throughout the Diocese. This is always a special time, when we gather to embrace our children into the faith of Christ through the laying on of hands. It is a time when we all remember that through the Holy Spirit, in the name of Jesus Christ, we find our strength, our comforter, and our peace. As always I ask that you please continue to pray for the Diocese of Jerusalem and its work. We are making great strides in pastoral care and development and we continue to strengthen our fellowship with local churches and partners from all around the world. I pray that as you head into the full activity of Autumn, that the Holy Spirit be with you, guide you and grant you the peace that is beyond understanding. Salaam, + Suheil Dawani Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem www.j-diocese.org [email protected] Editor: The Rt Revd Bishop Suheil S.Dawani Page 1 The Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem Newsletter Summer Camps in Nazareth and Jordan Children and youth from Primary, Elementary, and Secondary grades gathered from throughout Israel and Palestine at St. -

Southwell Leaves News and Information from Southwell Minster

Southwell Leaves News and Information from Southwell Minster April /May 2020 £2.50 www.southwellminster.org Follow us on twitter @SouthwMinster 1 Southwell Leaves April-May 2020 Contents… House Groups House Groups 2 Welcome 3 ith the beginning of Bible Verses for Reflection 3 W Lent the 2019/2020 From the Dean 4 Minster House Group series From Canon Precentor/ Pause for Thought 5 came to an end. As previously some seventy people had The Man from Galilee 6/7 gathered in groups of between Leaves of Southwell Dementi, Mental ten and five, fortnightly between September and the beginning of Advent, and Health & Learning Disabilities Outreach again a few times between Christmas and Shrove Tuesday. In response to requests for bible study the suggested theme was material from the Bible Project 7 Society’s Word lyfe stream. This focuses on three areas – being immersed in Meet Jonny Allsopp 8 the word of God, sharing faith and getting to know Jesus better. Over five Southwell Music Festival Launch 8 sessions the material suggested how scripture might offer ways of being immersed in the Christian message, of reflecting upon Jesus as saviour, of On the Road to Emmaus 9 sensing the transforming power of the Holy Spirit, of feeling how Christ’s Holocaust Memorial Day Event 10 followers are called to live distinctly different lives and how we might explore ways in which a post-Christian world might engage with the great story of National Holocaust Centre & Museum 11 Christ. New Bishop of Sherwood appointed 11 Son of Man / Some GreenTips 12 The material is quite structured and groups had differing experiences of it, but as ever the House Groups supported fellowship and learning together. -

Israel-PALESTINE FOOTSTEPS in PEACE

A Program of pilgrimage and discovery Israel-PALESTINE FOOTSTEPS IN PEACE THURSDAY, OCTOBER 20 to WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 2022 13 nights / 14 days 36 meals _____________________________ Facilitators: Dean Dr. Christopher Pappas, Vancouver BC Canon Dr. Richard LeSueur, Canmore AB Itinerary Summary : Jerusalem 4 nights Dan Hotel, Jerusalem Galilee 4 nights Kibbutz En Gev, Sea of Galilee Dead Sea 1 night David Dead Sea Resort & Spa Jerusalem 4 nights Ambassador Boutique Hotel Jerusalem (near the Old City) __________________________ Accommodation: Contact Phone Numbers Jerusalem March 10-14 Dan Hotel, Jerusalem 2Amr Ibn Al A’as Street 6 Phone: +972 2-627-7232 Sea of Galilee March 14-18 Kibbutz En Gev Phone: +972-4-665-9800 Dead Sea March 18-19 David Dead Sea Resort & Spa Ein Bokek, +972 8-659-1234 Jerusalem, March 19-23 Ambassador Boutique Hotel 5 Ali Iben Abu Taleb, Jerusalem +972 2-632-5000 Land Agency CTM Tours, Jerusalem, Israel Meals indicated B – breakfast / L – lunch / D – dinner Modest Dress (M) Men : long pants or zip-ons to cover legs Women : knees, shoulders & elbows covered 2 Thursday, October 20 Day 1 Arrival at Ben Gurion Dan Hotel D Arrival at Ben Gurion International Airport. One is transferred to Jerusalem, about an hours’ drive, for a restful first night. Check into Dan Hotel 5:30pm Group reception and welcome 6:30pm Dinner Friday, October 21 Day 2 Introducing Jerusalem & Bethlehem Dan Hotel BLD The day begins with an orientation briefing. We then travel around the walls of the Old City onto the Mount of Olives to overlook the city. -

Sabeel Wave of Prayer

abeel Wave of Prayer July 2nd, 2020 S This prayer ministry enables local and international friends of Sabeel to pray over regional concerns on a weekly basis. Sent to Sabeel’s network of supporters, the prayer is used in services around the world and during Sabeel’s Thursday Communion service; as each community in its respective time zone lifts these concerns in prayer at noon every Thursday, this “wave of prayer” washes over the world. In Week 37 of the Kumi Now Initiative anyone who had registered for an online gathering was treated to a special evening celebrating Palestinian music and poetry. Next Tuesday, the 7th of July there will be an online session addressing Morally Responsible Investing with Sabeel-Kairos UK, at 6pm, Palestine Time, (for details see: http:/www.kuminow. com/online) • Dear Lord, we thank you for the rich heritage of Palestinian music, poetry, and painting. We thank you for the artists who keep their inheritance alive by using their gifts to reach out to their people at a time of suffering. Lord, in your mercy... Hear our prayer. There has been a spike of Covid19 infections across Palestine, including outbreaks in Nablus and Hebron. 195 new infections were recorded on Sunday, 28th June and this resurgence in cases has necessitated lockdowns throughout the West Bank, including a 2-day lockdown of Bethlehem, the banning of all weddings, and the closure of churches and mosques across the West Bank. • Lord, we ask that wisdom would be granted to all those with responsibility to try to contain these new outbreaks of the coronavirus in the occupied Palestinian Territories. -

COMMON GROUND the Magazine of the Council of Christians and Jews / Spring 2020

COMMON GROUND The magazine of The Council of Christians and Jews / Spring 2020 Raise up, Remember, Repair Dialogue in a new decade Tony Kushner and Carolyn Amy-Jill Levine on the Paula Fredriksen on Sanzenbacher on ccj Jewishness of Jesus the Apostle Paul pioneer James Parkes The Council of Christians and Jews Patron Her Majesty the Queen Presidents The Archbishop of Canterbury The Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster The Archbishop of Thyateira and Great Britain The Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland The Moderator of the Free Churches The Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth The Senior Rabbi of Masorti Judaism The Senior Rabbi to Reform Judaism The Senior Rabbi & Chief Executive of Liberal Judaism The Spiritual Head, Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ Congregation Vice Presidents Lord Carey of Clifton The Revd Dr David Coffey Mrs Elizabeth Corob Mr Henry Grunwald OBE QC The Rt Revd Lord Harries of Pentregarth The Rt Revd Dr Christopher Herbert Mr Clive Marks OBE FCA Mr R Stephen Rubin OBE Rt Hon Sir Timothy Sainsbury The Revd Malcolm Weisman OBE Trustees Chair: The Rt Revd Dr Michael Ipgrave OBE Vice Chairs: Lord Farmer, Mr Maurice Ostro OBE, KFO Hon. Treasurers: Mr Andrew Mainz FCA, Mr Duncan Irvine Hon. Secretaries: The Revd Patrick Moriarty, Rabbi David Mason Lord Howard of Lympne, Mr Zaki Cooper, Mr Michael Hockney MBE, Mr Vivian Wineman, Mr James Leek, Sr Teresa Brittain, Lord Shinkwin, Mr Tom Daniel Director Elizabeth Harris-Sawczenko Lisa Lillibridge is American and lives in Deputy Director the northeastern state The Revd Dr Nathan Eddy of Vermont. -

Jordan a Modern Kingdom in the Ancient Biblical Heartland CONTENTS

2/2021 Jordan A modern kingdom in the ancient biblical heartland CONTENTS JORDAN 2 Our little mustard seed has blossomed! Contemplation 4 The royal house guards the harmony The situation of Christians in Jordan 6 Christian tradition, a unique flair Despite their diff erences, the people in Al Fuheis practise good coexistence 8 Initiators of interfaith dialogue Why the Royal Family sees itself committed to religious tolerance 10 Building bridges between cultures Active for almost 60 years: the German-Jordanian Society 12 The chance to tread exceptional paths Refl ection on the pandemic and educational policy in Jordan 14 A minority of a minority The situation of Evangelical Christians in Jordan 17 Contact with parents has become closer How the TSS stays on course during the pandemic NEWS FROM THE SCHNELLER WORK 19 Group shaves off their hair Alumni reminisce 20 Every child is important How the Schneller school supports children during the pandemic 22 Four partners for one school JLSS, EVS, EMS and the Beirut Church sign new agreement 24 Don‘t be misled by small numbers EMS Near East Liaison Desk moderates international partner consultation of the NEST 26 Time for verbal disarmament An obituary and a review 28 Letters to the editors 31 Jean Etre obituary Cover photo: Two boys at the Theodor Schneller School in Amman (EMS/Gräbe) Back cover: Caravan in Wadi Rum (Nabiel Khubeis) EDITORIAL Dear Reader, It is one hundred years since the state that is now the Hashe- mite Kingdom of Jordan was founded. It could have remained a footnote in history as it was only a temporary attempt by the British mandatory power to forge a balance between various diff erent interests and promises in the Middle East on a parcel of land that was inhospitable and poor in raw materials – but it was never designed to be permanent. -

Bethlehem Prayer Service

“For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord.” —Luke 2:11 Bethlehem Prayer Service Simulcast from Washington National Cathedral in washington, dc • 10:00 am & The Evangelical Lutheran Christmas Church in bethlehem, palestine • 5:00 pm December 19, 2015 Bethlehem Prayer Service simulcast from washington, dc & bethlehem, palestine december 19, 2015 N organ voluntary Gigue – Go, tell it on the mountain A.D. Miller (b. 1972) Partita – In dulci jubilo James Vivian (b. 1974) choral prelude Choirs of St. Alban’s Church and St. John’s, Norwood • Washington, DC Nativity Carol John Rutter (b. 1945) Sir Christèmas William Mathias (1934-1992) O nata lux Morten Lauridsen (b. 1943) prelude hymn Christmas Church Lutheran Band/Brass for Peace • Bethlehem Man ya tura welcome The Reverend Dr. Mitri Raheb, Senior Pastor The Evangelical Lutheran Christmas Church • Bethlehem opening hymn Sung by all, standing • Christmas Church O come, all ye faithful 2 opening greeting and acclamation The Right Reverend Mariann Edgar Budde, Bishop of Washington • Washington, DC Bp Mariann By the tender mercy of our God, the dawn from on high will break upon us to give light to those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death, People To guide our feet into the way of peace. Bp Mariann Beloved, in this Holy Season we gather in Bethlehem and in Washington to celebrate the great gift with which God blesses all Creation in the birth of Jesus Christ our Lord. Let us hear and receive the Good News of Christ, and offer to God our thanksgiving in joyful songs of praise. -

November 2014 Newsletter

November 2014 Newsletter The Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem Peace to you in the Name of the Lord Greetings from Archbishop Suheil Dawani Dear Friends, As we move into the hope-filled season of Advent, we have many reasons to celebrate. Our annual Majma (Synod) meeting in Amman affirmed the new direction of the Diocese as we seek to bolster our parishes and institutions and, in turn, improve our services to the wider community. During my visit to Beirut and official visits to the West Bank municipalities of Hebron and Nablus, I was reminded of the great potential of the people of this land, as well as the critical need for our Diocese to continue to support individuals, families and communities in living out this God given potential. In Jerusalem, the Heads of Churches and interfaith community banded together to call for an end to the recent cycle of violence, confident that religion need not be divisive, but rather a force for good, especially when it promotes peace, justice and reconciliation. In spite of all the challenges in this region, with the grace of God and the support of our friends, we are able to hold firm and, through our parishes, and institutions of healthcare and learning, make a positive contribution throughout the Middle East. I pray that this Christmas season, as you celebrate the coming of the Prince of Peace, your lives will be blessed with love, peace and joy! Salaam, Peace Archbishop Suheil Dawani Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem www.j-diocese.org [email protected] Editor: The Most Rev’d Archbishop Suheil S. -

Israel at 65 – Between Domestic Change and Regional Instability KAS & AJC Seminar in Israel on the German-US-Israeli-Relationship

Israel at 65 – Between Domestic Change and Regional Instability KAS & AJC Seminar in Israel on the German-US-Israeli-Relationship 13.-19. Juli 2013 Hintergrund Die Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) und das American Jewish Committee (AJC) verbindet eine vertrauensvolle Zusammenarbeit, die seit mehr als 30 Jahren besteht. Kernelement dieser Kooperation ist das deutsch-amerikanische Austauschprogramm, das beide Partner gemeinsam verantworten. Einmal im Jahr organisiert die KAS ein Besucherprogramm für AJC-Mitglieder aus den USA in Deutschland. Das Programm verfolgt das Ziel, den amerikanischen Teilnehmern einen Eindruck davon zu vermitteln, wie die Bundesrepublik mit ihrer historischen Verantwortung für den Holocaust umgeht und sich um Aufarbeitung, Erinnerung und Prävention bemüht. Zugleich werden den Teilnehmern Kenntnisse über die politischen und gesellschaftlichen Entwicklungen der jüngsten Zeit in Deutschland und Europa vermittelt und Möglichkeiten zum Dialog mit deutschen Gesprächspartnern über Fragen des deutsch-jüdischen Verhältnisses gegeben. Das Austauschprogramm bietet darüber hinaus den amerikanischen Gästen die Gelegenheit, einen Einblick in das Leben und den Alltag der jüdischen Gemeinde in Deutschland zu erhalten. Umgekehrt reist ebenfalls jährlich eine Gruppe deutscher Nachwuchskräfte in die USA, um dort die Bedeutung sowie die Arbeits- und Funktionsweise des AJC kennenzulernen. Den Teilnehmern bietet sich darüber hinaus die Gelegenheit, ein Verständnis für die aktuellen politischen Entwicklungen in den USA zu entwickeln, das dortige jüdische politische und gesellschaftliche Leben kennenzulernen und sich mit der Geschichte des Holocaust aus einem jüdisch-amerikanischen Blickwinkel auseinanderzusetzen. Beide Programme dienen im Wesentlichen der Festigung des deutsch/jüdisch- amerikanischen Verhältnisses und genießen in der Arbeit der KAS und des AJC eine hohe Priorität. Vor diesem Hintergrund fand vom 13.-19. -

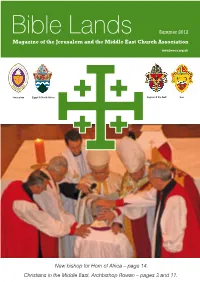

Christians in the Middle East, Archbishop Rowan – Pages 3 and 11

Bible Lands Summer 2012 Magazine of the Jerusalem and the Middle East Church Association www.jmeca.org.uk & TH M E M LE ID SA DL RU E E EA J S N T I D H I C O R C E U S H E C O L F A J P E O R C U S S I A P L E E M E H T Jerusalem Egypt & North Africa Cyprus & the Gulf Iran New bishop for Horn of Africa – page 14. Christians in the Middle East, Archbishop Rowan – pages 3 and 11. THE JERUSALEM AND Bible Lands Editor Letters, articles, comments are welcomed by the Editor: THE MIDDLE EAST CHURCH Canon Timothy Biles, 36 Hound Street, ASSOCIATION Sherborne DT9 3AA Tel: 01935 816247 Email: [email protected] (JMECA) The next issue will be published in November for Winter 2012/13. Founded in 1887 Views expressed in this magazine are not necessarily ‘To encourage support in prayer, money and those of the Association; therefore only signed articles personal service for the religious and other will be published. charitable work of the Episcopal church in JMECA Website www.jmeca.org.uk Jerusalem and the Middle East’. The site has information for each of the four Dioceses Reg. Charity no. 248799 with links to the websites of each one and regular www.jmeca.org.uk updates of Middle East news. Patron THE CENTRAL SYNOD OF THE PROVINCE The Most Reverend and Right Honourable The Archbishop of Canterbury President The Most Revd Dr Mouneer Anis Chairman Secretary Mr.