Remembering Robert K. Merton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Social Theory

CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL THEORY General Editor: ANTHONY GIDDENS This series aims to create a forum for debate between different theoretical and philosophical traditions in the social sciences. As well as covering broad schools of thought, the series will also concentrate upon the work of particular thinkers whose ideas have had a major impact on social science (these books appear under the sub-series title of 'Theoretical Traditions in the Social Sciences'). The series is not limited to abstract theoretical discussion - it will also include more substantive works on contemporary capitalism, the state, politics and other subject areas. Published titles Tony Bilton, Kevin Bonnett, Philip Jones, Ken Sheard, Michelle Stanworth and Andrew Webster, Introductory Sociology Simon Clarke, Marx, Marginalism and Modern Sociology Emile Durkheim, The Division of Labour in Society (trans. W. D. Halls) Emile Durkheim, The Rules of Sociological Method (ed. Steven Lukes, trans. W. D. Halls) Boris Frankel, Beyond the State? Anthony Giddens, A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism Anthony Giddens, Central Problems in Social Theory Anthony Giddens, Profiles and Critiques in Social Theory Anthony Giddens and David Held (eds), Classes, Power and Conflict: Classical and Contemporary Debates Geoffrey Ingham, Capitalism Divided? Terry Johnson, Christopher Dandeker and Clive Ashworth, The Structure of Social Theory Douglas Kellner, Herbert Marcuse and the Crisis of Marxism Jorge Larrain, Marxism and Ideology Ali Rattansi, Marx and the Division of Labour Gerry -

Comparing Capitalisms Through the Lens of Classical Sociological Theory1

Comparing Capitalisms through the Lens of Classical Sociological Theory1 Gregory Jackson 1 Introduction The ‘classical tradition’ in sociology, stemming from Marx, Durkheim, and We- ber, continues to inspire sociological approaches to the economy (Beckert 2002; Swedberg 2000). Despite its foundational infl uence, the distinctively sociologi- cal contribution of this ‘classical’ tradition has been somewhat overshadowed by the widespread diffusion of economic theory, such as transaction costs or agency theory, and newer sociological approaches, such as network analysis or ‘new institutionalism’ in organizational analysis, in the process of forging inter- disciplinary approaches to the economy. In honor of the sixtieth birthday of Wolfgang Streeck, this essay looks at his contribution to economic sociology and its relationship to classical sociological theory. Wolfgang Streeck has retained and developed a distinctly sociological approach to the study of the economy that draws important inspiration from the classics. His closeness to the classic sociological tradition is perhaps unsur- prising given his early journey as a student in the 1970s from the ‘critical theory’ found in Frankfurt to the then often more ‘middle range’ concerns of sociology pursued at Columbia University by infl uential fi gures such as Robert Merton, Peter Blau, and Amitai Etzioni. Wolfgang Streeck was excited by the empiri- cal richness of early American sociology, as is evident in his subsequent edited volume Elementare Soziologie (1976). Alongside Durkheim, Weber, and Friedrich Engels, the book translated writings of postwar American sociologists such as Peter Blau, Alvin Gouldner, Howard Becker, and William Whyte. However, the focus was not on positivist empirical sociology, but on the way these sociologists utilized fundamental theoretical concepts, such as confl ict, exchange, or status, to inform their detailed empirical or even ethnographic fi eldwork. -

The Revival of Economic Sociology

Chapter 1 The Revival of Economic Sociology MAURO F. G UILLEN´ , RANDALL COLLINS, PAULA ENGLAND, AND MARSHALL MEYER conomic sociology is staging a comeback after decades of rela- tive obscurity. Many of the issues explored by scholars today E mirror the original concerns of the discipline: sociology emerged in the first place as a science geared toward providing an institutionally informed and culturally rich understanding of eco- nomic life. Confronted with the profound social transformations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the founders of so- ciological thought—Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, Georg Simmel—explored the relationship between the economy and the larger society (Swedberg and Granovetter 1992). They examined the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services through the lenses of domination and power, solidarity and inequal- ity, structure and agency, and ideology and culture. The classics thus planted the seeds for the systematic study of social classes, gender, race, complex organizations, work and occupations, economic devel- opment, and culture as part of a unified sociological approach to eco- nomic life. Subsequent theoretical developments led scholars away from this originally unified approach. In the 1930s, Talcott Parsons rein- terpreted the classical heritage of economic sociology, clearly distin- guishing between economics (focused on the means of economic ac- tion, or what he called “the adaptive subsystem”) and sociology (focused on the value orientations underpinning economic action). Thus, sociologists were theoretically discouraged from participating 1 2 The New Economic Sociology in the economics-sociology dialogue—an exchange that, in any case, was not sought by economists. It was only when Parsons’s theory was challenged by the reality of the contentious 1960s (specifically, its emphasis on value consensus and system equilibration; see Granovet- ter 1990, and Zelizer, ch. -

Entretien Helga Nowotny: an Itinerary Between Sociology of Knowledge and Public Debate

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/82552 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-06 and may be subject to change. Natures Sciences Sociétés 17,57-64 (2009) Disponible en ligne sur : © NSS Dialogues, EDP Sciences 2009 www.nss-journal.org N a tu re s DOI: 10.1051/nss/2009010 Sciences Sociétés Entretien Helga Nowotny: an itinerary between sociology of knowledge and public debate Interview by Pieter Leroy Helga Nowotny1, Pieter Leroy2 1 Professor emeritus Social Studies of Science, ETH, Zurich; Vice-President of the European Research Council 2 Professor of Political Sciences of the Environment, Nijmegen University, 6500 HK Nijmegen, The Netherlands Helga Nowotny, professor emeritus nowadays, is a grand lady in the field that was originally labelled sociology of knowledge, and gradually became better known as STS: science and technology studies. As is clear from "Short biography" (Box 1) and "Research and publications" (Box 3), Helga Nowotny's œuvre is impressive and addresses a variety of issues. The interview deliberately focuses on themes that are close to the NSS agenda: knowledge production, the field of STS and the governance of research, starting, self-evidently, with a retrospect on Helga Nowotny's earlier work. Pieter Leroy (NSS): How was it that you got a doctor P.L.: Was there a particular professor at Columbia who ate in law from Vienna University (1959) and then w ent got your attention? to the USA, more precisely to Columbia University, to get Helga Nowotny: The day after I had decided that I a PhD (1969)? wanted to obtain a PhD in sociology at Columbia, I went Helga Nowotny: Following my doctorate in law to see Paul F. -

The Ambivalence of Social Change. Triumph Or Trauma

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sztompka, Piotr Working Paper The ambivalence of social change: Triumph or trauma? WZB Discussion Paper, No. P 00-001 Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Sztompka, Piotr (2000) : The ambivalence of social change: Triumph or trauma?, WZB Discussion Paper, No. P 00-001, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/50259 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu P 00 - 001 The Ambivalence of Social Change Triumph or Trauma? Piotr Sztompka Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung gGmbH (WZB) Reichpietschufer 50, D-10785 Berlin Dr. Piotr Sztompka is a professor of sociology at the Jagiellonian University at Krakow (Poland), where he is heading the Chair of Theoretical Sociology, as well as the Center for Analysis of Social Change "Europe '89". -

Thomas Theorem and the Matthew Hfed?

The Thomas Theorem and The Matthew Hfed? ROBERT K MERI'ON, Cohmbiu University and Russell Sage Foundation Eponymy in science is the practice of affixing the names of scientists to what they have discovered or are believed to have discovered,’ as with Boyle’s Law, Halley’s comet, Fourier’s transform, Planck’s constant, the Rorschach test, the Gini coefficient, and the Thomas theorem This article can be read from various sociological perspectives? Most specifical- ly, it records an epistolary episode in the sociointellectual history of what has ’ The definition of epw includes the cautionary phrase,“or are belkvedto have discovered,” in order to take due note of “Stigkr’s Law of Eponymy” which in its strongest and “simplest form is this: ‘No scientific discovery is named after its original discovereV (Stigler 1980). Stigler’s study of what is generally known as “the normal distribution” or “the Gaussian distribution” as a case in point of his ixonicaBy self-exemplifyingeponymous law is based in part on its eponymous appearance in 80 textbooks of statistics, from 1816 to 1976. 2 As will become evident, this discursive composite of archival dccuments, biography of a sociological idea, and analysis of social mechanisms involved in the diffusion of that idea departs from the tidy format that has come to be p&bed for the scientific paper. This is by design and with the indulgent consent of the editor of SocialForces. But then, that only speaks for a continuing largeness of spirit of its editorial policy which, back in 1934, allowed the ironic phrase “enlightened Boojum of Positivism” (with its allusion to Lewis Carroll’s immortal The Hunting of the &ark) to appear in my very fist article, published in this journal better than 60 Y- ago. -

Social Theory's Essential Texts

Conference Information Features • Znaniecki Conference in Poland • The Essential Readings in Theory • Miniconference in San Francisco • Where Can a Student Find Theory? THE ASA July 1998 THEORY SECTION NEWSLETTER Perspectives VOLUME 20, NUMBER 3 From the Chair’s Desk Section Officers How Do We Create Theory? CHAIR By Guillermina Jasso Guillermina Jasso s the spring semester draws to a close, and new scholarly energies are every- where visible, I want to briefly take stock of sociological theory and the CHAIR-ELECT Theory Section. It has been a splendid privilege to watch the selflessness Janet Saltzman Chafetz A and devotion with which section members nurture the growth of sociological theory and its chief institutional steward, the Theory Section. I called on many of you to PAST CHAIR help with section matters, and you kindly took on extra burdens, many of them Donald Levine thankless except, sub specie aeternitatis, insofar as they play a part in advancing socio- logical theory. The Theory Prize Committee, the Shils-Coleman Prize Committee, SECRETARY-TREASURER the Nominations Committee, and the Membership Committee have been active; the Peter Kivisto newsletter editor has kept us informed; the session organizers have assembled an impressive array of speakers and topics. And thus, we can look forward to our COUNCIL meeting in August as a time for intellectual consolidation and intellectual progress. Keith Doubt Gary Alan Fine The section program for the August meetings includes one regular open session, one Stephen Kalberg roundtables session, and the three-session miniconference, entitled “The Methods Michele Lamont of Theoretical Sociology.” Because the papers from the miniconference are likely to Emanuel Schegloff become the heart of a book, I will be especially on the lookout for discussion at the miniconference sessions that could form the basis for additional papers or discus- Steven Seidman sion in the volume. -

Helga Nowotny: an Itinerary Between Sociology of Knowledge and Public Debate

Natures Sciences Sociétés 17, 57-64 (2009) Disponible en ligne sur : © NSS Dialogues, EDP Sciences 2009 www.nss-journal.org N a t u r e s DOI: 10.1051/nss/2009010 Sciences Sociétés Entretien Helga Nowotny: an itinerary between sociology of knowledge and public debate Interview by Pieter Leroy Helga Nowotny1, Pieter Leroy2 1 Professor emeritus Social Studies of Science, ETH, Zurich; Vice-President of the European Research Council 2 Professor of Political Sciences of the Environment, Nijmegen University, 6500 HK Nijmegen, The Netherlands Helga Nowotny, professor emeritus nowadays, is a grand lady in the field that was originally labelled sociology of knowledge, and gradually became better known as STS: science and technology studies. As is clear from “Short biography” (Box 1) and “Research and publications” (Box 3), Helga Nowotny’s œuvre is impressive and addresses a variety of issues. The interview deliberately focuses on themes that are close to the NSS agenda: knowledge production, the field of STS and the governance of research, starting, self-evidently, with a retrospect on Helga Nowotny’s earlier work. Pieter Leroy (NSS): How was it that you got a doctor- P.L.: Was there a particular professor at Columbia who ate in law from Vienna University (1959) and then went got your attention? to the USA, more precisely to Columbia University, to get Helga Nowotny: The day after I had decided that I a PhD (1969)? wanted to obtain a PhD in sociology at Columbia, I went Helga Nowotny: Following my doctorate in law to see Paul F. Lazarsfeld, an Austrian emigrant scientist I worked at the University of Vienna as an assistant who had left Vienna before Hitler took over. -

Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 12-2008 Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Jefferson Pooley Muhlenberg College Elihu Katz University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pooley, J., & Katz, E. (2008). Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research. Journal of Communication, 58 (4), 767-786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00413.x This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/269 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Abstract Communication research seems to be flourishing, as vidente in the number of universities offering degrees in communication, number of students enrolled, number of journals, and so on. The field is interdisciplinary and embraces various combinations of former schools of journalism, schools of speech (Midwest for ‘‘rhetoric’’), and programs in sociology and political science. The field is linked to law, to schools of business and health, to cinema studies, and, increasingly, to humanistically oriented programs of so-called cultural studies. All this, in spite of having been prematurely pronounced dead, or bankrupt, by some of its founders. Sociologists once occupied a prominent place in the study of communication— both in pioneering departments of sociology and as founding members of the interdisciplinary teams that constituted departments and schools of communication. In the intervening years, we daresay that media research has attracted rather little attention in mainstream sociology and, as for departments of communication, a generation of scholars brought up on interdisciplinarity has lost touch with the disciplines from which their teachers were recruited. -

Lipset 2020 Program FINAL V4.Indd

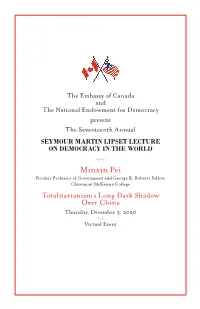

The Embassy of Canada and The National Endowment for Democracy present The Seventeenth Annual SEYMOUR MARTIN LIPSET LECTURE ON DEMOCRACY IN THE WORLD Minxin Pei Pritzker Professor of Government and George R. Roberts Fellow, Claremont McKenna College Totalitarianism’s Long Dark Shadow Over China Thursday, December 3, 2020 Virtual Event Minxin Pei Pritzker Professor of Government and George R. Roberts Fellow, Claremont McKenna College Dr. Minxin Pei is the Tom and Mar- Trapped Transition: The Limits of Develop- got Pritzker ’72 Professor of Gov- mental Autocracy (Harvard University ernment and George R. Roberts Fel- Press, 2006), and China’s Crony Capi- low at Claremont McKenna College. talism: The Dynamics of Regime Decay (Har- He is also a non-resident senior fel- vard University Press, 2016). His low of the German Marshall Fund of research has been published in For- the United States. He serves on the eign Policy, Foreign Affairs, The National In- editorial board of the Journal of Democ- terest, Modern China, China Quarterly, Jour- racy and as editor-in-chief of the Chi- nal of Democracy, and in numerous na Leadership Monitor. Prior to joining edited volumes. Claremont McKenna in 2009, Dr. Dr. Pei’s op-eds have appeared Pei was a senior associate and the di- in the Financial Times, New York Times, rector of the China Program at the Washington Post, Newsweek International, Carnegie Endowment for Interna- and other major newspapers. Dr. tional Peace. Pei received his Ph.D. in political A renowned scholar of democra- science from Harvard University. tization in developing countries, He is a recipient of numerous pres- economic reform and governance tigious fellowships, including the in China, and U.S.-China rela- National Fellowship at the Hoover tions, he is the author of From Reform Institution at Stanford University, to Revolution: The Demise of Communism in the McNamara Fellowship at the China and the Soviet Union (Harvard World Bank, and the Olin Faculty University Press, 1994), China’s Fellowship of the Olin Foundation. -

PART I the Columbia School 10 Peter Simonson the Columbia and Gabriel School Weimann

Critical Research at Columbia 9 PART I The Columbia School 10 Peter Simonson The Columbia and Gabriel School Weimann Introduction That canonic texts refuse to stand still applies, a fortiori, to the classics of the Columbia “school.” The pioneering work of Paul Lazarsfeld and associates in the 1940s and 1950s gave communications research its very name and yet, at the same time, evoked devastating criticism. The Chi- cago school decried Columbia’s psychologistic and positivistic bias and denounced its pronouncement of “limited effects”; the Frankfurt school refused to accept that audience likes and dislikes had any bearing on understanding the culture industry; and British cultural studies threw darts at the idea of defining media functions by asking audiences how they “use” them. Todd Gitlin went so far as to accuse Lazarsfeld’s “domin- ant paradigm” of willfully understating the persuasive powers of the media, thereby relieving their owners and managers of the guilt they ought to feel. It is true that the Columbia school – not satisfied to infer effects from content – developed methodologies for studying audience attitudes and behavior; it is true that sample surveys were preferred to ethnographic study or other forms of qualitative analysis; it is true that many studies were commercially sponsored, even if their products were academic; and it is true that media campaigns, like it or not, have only limited effects on the opinions, attitudes, and actions of the mass audience. But it is also true that, in the meantime, some of Columbia’s harshest critics have themselves turned (perhaps too much so) to “reception” studies – that is to say, toward Columbia-like observations of the relative autonomy of audience decodings. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar).