Patterns of Disparity: Small Business Lending in Illinois

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Porton Target

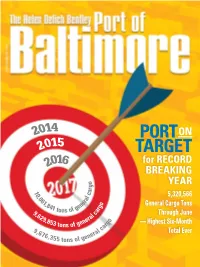

2014 PORT ON 2015 TARGET 2016 for RECORD BREAKING o YEAR g r 1 a 0 c 5,320,566 ,0 l 61 ra , e o General Cargo Tons 84 n g 1 t f ge r 9 ons o a Through June ,6 l c 29 ra ,85 ne o — Highest Six-Month 3 tons of ge rg ca 9,6 al Total Ever 76 ner ,355 tons of ge Celebrating 100 Years! Our Foundation’s Legacy is Always With Us: Uncommon Dedication and Integrity John S. Connor 1890-1940 Husband, Father, Friend, Merchant Founder, 1917: John S. Connor, Inc Frank Burkhardt BalTerm employee for 11 years One of our most important assets. Cleanliness, and the employees who keep it but its that kind of attention to detail that puts that way. Partner with the company BalTerm in a class by itself. Our that’s cleaning up when it comes warehouse floors are as polished to forest products warehousing, as our reputation. And if our floors stevedoring and cargo handling. BALTIMORE FOREST PRODUCTS TERMINALSget this much attention, imagine Of course, some might consider us the attention we give to everything a bit obsessive about keeping our else. At BalTerm, our assets are warehouses and equipment clean, your assets�. BALTIMORE FOREST PRODUCTS TERMINALS www.BalTerm.com South Locust Point Marine Terminal 2001 East McComas St. Baltimore, MD 21230 410.752.9981 BALTIMORE FOREST PRODUCTS TERMINALS ™ MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION’S MARYLAND PORT ADMINISTRATION World Trade Center Baltimore, 401 E. Pratt St. Baltimore, MD 21202 | Toll Free 1-800-638-7519 GOVERNOR LIEUTENANT Larry Hogan GOVERNOR Executive Director General Manager of Intermodal / Boyd Rutherford James J. -

About Xavier Xavier Athletic Communications Big East

VOLLEYBALL | 2014 SUPPLEMENTAL GUIDE ABOUT XAVIER VOLLEYBALL INFORMATION School ................................................. Xavier University 2013 Overall Record ............................................. 21-11 City/Zip ........................................ Cincinnati, OH 45207 2013 Conference Record ............ 12-4 (T-2nd BIG EAST) Founded ..................................................................1831 2013 BIG EAST Tournament Finish ................ 0-1/(T-3rd) Enrollment .............................................................6,650 2013 Postseason .......................................................N/A Nickname .................................................... Musketeers Home Record .......................................................... 10-3 Colors ...................................Navy Blue, Gray and White Road Record ............................................................. 8-5 Facility (Capacity; Yr. Built) Cintas Center (10,250; 2000) Neutral ...................................................................... 3-3 Conference ..................................................... BIG EAST Longest 2013 Winning Streak ...................................... 4 President......................................Michael J. Graham, S.J. Players Returning/Lost .............................................9/4 Athletic Director ................................ Greg Christopher Starters Returning/Lost ............................... 4+Libero/2 Athletic Website ............................www.GOXAVIER.com -

Emerging Trends in Real Estate® 2019

RYAN DRAVITZ RYAN Emerging Trends in Real Estate® United States and Canada 2019 2019_EmergTrends US_C1_4.indd 1 9/7/18 2:57 PM Emerging Trends in Real Estate® 2019 A publication from: 2019_EmergTrends US_C1_4.indd 2 9/7/18 2:57 PM Emerging Trends in Real Estate® 2019 Contents 1 Notice to Readers 54 Chapter 4 Property Type Outlook 55 Industrial 3 Chapter 1 New Era Demands New Thinking 59 Single- and Multifamily Overview 4 Intensifying Transformation 59 Apartments 6 Easing into the Future 64 Single-Family Homes 8 18-Hour Cities 3.0: Suburbs and Stability 67 Office 9 Amenities Gone Wild 71 Hotels 10 Pivoting toward a New Horizon 73 Retail 11 Get Smart: PI + AI 13 The Myth of “Free Delivery” 76 Chapter 5 Emerging Trends in Canadian 15 Retail Transforming to a New Equilibrium Real Estate 16 Unlock Capacity 76 Industry Trends 18 We’re All in This Together 82 Property Type Outlook 20 Expected Best Bets for 2019 87 Markets to Watch in 2019 20 Issues to Watch in 2019 91 Expected Best Bets for 2019 23 Chapter 2 Capital Markets 93 Interviewees 24 The Debt Sector 30 The Equity Sector 35 Summary 36 Chapter 3 Markets to Watch 36 2019 Market Rankings 38 South: Central West 39 South: Atlantic 40 South: Florida 41 South: Central East 42 Northeast: Mid-Atlantic 43 Northeast: New England 44 West: Mountain Region 45 West: Pacific 46 Midwest: East 47 Midwest: West Emerging Trends in Real Estate® 2019 i Editorial Leadership Team Emerging Trends Chairs PwC Advisers and Contributing Researchers Mitchell M. -

KLOECKNER METALS BRANCH ADDRESSES with Region, WC

Color Legend on Last Page KLOECKNER METALS BRANCH ADDRESSES Red Print signifies most recent with Region, WC, Environmental, Safety, and Fleet Contacts Regiona EVP. Reg. Branch Mgr. Branch President, Regional Reg. Ops. Manager Code Branch and Region Manager Gen./Assit. Manager Operations Manager Safety Environmental Regional Safety Mgr. Workers Comp Fleet Address Phone Notes AFI Nashville, TN Bob DeMarco, EVP Mark Zumbrun John Paulk Bryan Black Bryan Black Patrick Lydon (Thomas) Dorothy Gesick-Cheeney Shane (Alan) Watson 570 Metroplex Drive 615-834-8700 American Fabricators (Located In DFW) Director of Fabrication Assistant Operations tlydon@... (awatson@...) Nashville, TN 37211 East Region Bob Driscoll Manager Regional Manager (located AFI) ALP Alpharetta, GA Bob DeMarco, EVP-East Bill West Bill West Bill West Patrick Lydon (Thomas) Bill West Billy Tuggle 1950 McFarland/400 Blvd. 770-752-8100 East Region (loccated in DFW) tlydon@... Alpharetta, GA 30004 800-827-8335 Scott Tabler Regional Manager (located in ALP) APP Alpharetta, GA Bob DeMarco,EVP Sean Heenan Ann Leonard Ann Leonard Ron Walker Cindy Piper Josh Norris 2005 Grassland Parkway 770-751-1172 (Atlanta Plate) General Manager Alpharetta, GA 30004 800-433-581 East Region AMA Amarillo, TX Jason Albro EVP Isaac Matt Chattin Adam Robbins Adam Robbins Adam Robbins Steven McOmber Stephanie Spillers Adam Robbins 5425 North Whitaker Road 806-383-7141 West Region Moss Reg. Mgr. General Manager Amarillo, TX 79108 800-725-5253 APA Apache Junction John Paschal, President, Paul Zisimopoulos Paul Zisimopoulos Paul Zisimopoulos Paul Zisimopoulos Steven McOmber Tammee Ritter Tammee Ritter 2465 W. Houston Ave. 800-644-1933 Temtco - West Region Temtco Regional Operations Apache Junction, AZ 85120 480-288-2222 (located in LMS) Kevin Manager Welch Reg. -

Regional Land Use Leadership Institute

2012-2013 Directory Regional Land Use Leadership Institute Elizabeth Askew Senior Development Manager Mission First HDC 1330 New Hampshire Ave NW Suite 116 Washington, DC 20036 202-223-3405 (o) 202-223-9750 (f) [email protected] Elizabeth Askew works as Senior Development Manager for Mission First Housing Development Corporation, a nonprofit affordable housing developer based in the District of Columbia. Elizabeth holds a Bachelor’s degree in Environmental Policy from Duke University, and dual Masters’ degrees in Public Affairs and Urban and Regional Planning from the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton University. Prior to joining Mission First, Elizabeth worked in the environmental remediation field, aiding in the redevelopment of brownfield properties in the Chicago area. Elizabeth has also worked with the New Jersey Office of Management and Budget and the Oregon Department of Transportation, specializing in policy and performance analysis. She resides in the District of Columbia. Anthony Balestrieri President Balestrieri Real Estate Group 440 L Street NW Washington, DC 20001 202-236-5008 (o) [email protected] Mr. Balestrieri formed Balestrieri Associates in 2010 to invest, develop and advise on office, retail and residential properties in the Washington DC region. Previously he was a Director of Acquisitions & Development for Tishman Speyer in its Washington DC office. He was responsible for the identification of investment opportunities, valuation of income-producing and land development opportunities, financial and physical due diligence, and executing debt and sales transactions for commercial, residential and mixed use properties in the Washington DC market. Prior to joining Tishman Speyer, he worked for Akridge, a local Washington DC development firm sourcing and executing commercial real estate transactions. -

Prologis Profiles

PROLOGIS CORPORATE PROFILE I Fourth Quarter 2018 Prologis Profiles Prologis Headquarters, San Francisco, California The leading owner, operator and developer of logistics real estate, focused on GLOBAL AT A GLANCE (as of 12/31/2018) global and regional markets across the Americas, Europe and Asia. The company serves customers and investors as part of the global supply chain. Operates as a $87 B $51 B publicly traded real estate investment trust (REIT). in total assets under in Strategic Capital management assets Global Platform Active in 19 countries on four continents. 3,690 high-quality facilities in strategic locations serving global trade and regional distribution. The company specializes in 768 MSF 5,424 ACRES infill markets and develops logistics real estate typically near key seaports, airports (71 MSQM) (2,195 HECTARES) and major highway interchanges. owned, managed of land in key locations or under tied to regional distribution development and global trade Operations and Development 1,617 real estate professionals with extensive local market knowledge and development expertise to meet complex logistics and distribution requirements. 3,690 5,100 Customers include third-party logistics providers, transportation companies, retailers industrial properties customers across and manufacturers. across the Americas, a diverse range Europe and Asia of industries Strategic Capital Focused exclusively on high-quality global and regional logistics markets. Manages ~1,617 PLD approximately $59 billion in combined assets in 8 diverse funds and ventures colleagues serving NYSE publicly covering a broad risk/return spectrum. Co-investments typically range from 15 to customers and traded stock investors 55.0% percent. Corporate Responsibility Company approach encompasses environmental stewardship, social responsibility S&P 500 Global 100 member “Most Sustainable and ethics & governance. -

The Political Geography of Ohio, Michigan, and Missouri: Battlegrounds in the Heartland Ruy Teixeira and William Frey

The Political Geography of Ohio, Michigan, and Missouri: Battlegrounds in the Heartland Ruy Teixeira and William Frey This is the third in a series of reports on the demographic and political dynamics under way in key “battleground” states, deemed to be crucial in deciding the 2008 election. As part of the Metropolitan Policy Program’s Blueprint for American Prosperity, this series will provide an electoral component to the initiative’s analysis of and prescriptions for bolstering the health and vitality of America’s metropolitan areas, the engines of the U.S. economy. This report focuses on three major battleground states in the Midwest—Ohio, Michigan, and Missouri—and finds that: A. Ohio, Michigan and Missouri all feature eligible voter C. In Michigan, these trends will likely determine populations dominated by white working class voters. whether the fast-growing and populous Detroit sub- However, this profile is changing, albeit more slowly than urbs continue shifting toward the Democrats, a devel- in faster-growing states like Colorado or Arizona, as the opment which would tip the Detroit metro (44 percent white working class declines and white college graduates of the statewide vote) even farther in the direction of and minorities, especially Hispanics, increase. The largest the Democrats. The trends will also have a big impact on effects are in these states’ major metropolitan areas— whether the GOP can continue their hold on the conser- Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati in Ohio: Detroit in vative and growing Southwest region of the state that Michigan; and St. Louis and Kansas City in Missouri— includes the Grand Rapids metro. -

2012 WFTDA East Region Playoffs Hospitality Guide

WFTDA 2012 East Region Playoffs Hospitality Guide September 28-30, Burlington VT Champlain Valley Exposition Hosted by Green Mountain Derby Dames with Montreal Roller Derby Champlain Valley Exposition Where we skate105 Pearl St, PO Box 209, Essex Junction, VT 05453 cvexpo.com The Champlain Valley Exposition is the largest multi-purpose special events complex in Northern New England. With nearly 34,000 sq. ft. of clear-span, air conditioned exhibit space, significant available parking, and banquet capabilities, it is the perfect venue for major events requiring professional set-up and manage- ment. How to get there It is not feasible to walk from the host hotel to the venue. Consider reserving a rental car and parking in one of 5,000 attended parking spaces. Shuttles may be offered for the weekend, but specifics are un- known at this time. Should a shuttle bus be secured, we do not want not oversell passes and have people standing and waiting for buses to arrive. Therefore, we would likely limit the number of passes sold in order to provide prompt service. Check the tournament website and Facebook event page for announcements or consider renting a car. Security There will be hired security personnel and volunteer security staff from the Green Mountain Derby Dames and Montreal Roller Derby to attend to crowd control and general security matters. Nonetheless, you are advised not to leave valuables unattended as neither WFTDA, Green Mountain Derby Dames and Montreal Roller Derby nor the Champlain Valley Exposition can be responsible for loss, damage or theft of your belongings. Any property you bring to the event is at your own risk. -

Rochester; It's Got

$4.00 • so you're making your move to Rochester ... Have you seen Sibley's? Make us one of your first contacts and see all the ways we can make your life here more fun . Sibley's Is the largest department store between N.Y. C. and Cleveland, a division of Associated Dry Goods along with many other fine stores you may already know: We'll help you plan that new home. Our Interior Design Studio will help you add to what you have or start out brand new. And it doesn't cost a penny extra to get their advice . Sibley's Downtown Sibley's has It all . .. a wealth of merchandise! Fashions for the family, home furnishings, a Budget Store, a Gourmet Grocery and Bakery, a travel bureau, banking facilities , a photo studio, beauty salon, and a host of other services. Shop at home? Of course. We'll send our consultants to help you choose draperies, carpeting and slipcovers; show samples, measure floors and windows; give estimates. Just give us a call: 423-2969. Paying Is easy at Sibley's. You can open a regular 30-day charge account. Or, if you have a major credit card, you can open an instant mini-charge on the spot. If you'd like a little more time, we'll tailor a payment plan to your needs with a Convenient Budget Account. Sibley's Is nearby, no matter where in the Rochester area you live . Besides our big Downtown store, we have suburban stores at Greece Towne Mall , Irondequoit Plaza, Eastway Plaza, Newark Plaza, Eastview Mall and Southtown Plaza. -

Health of Massachusetts

Health of Massachusetts Deval L. Patrick Governor Commonwealth of Massachusetts Timothy P. Murray Lt. Governor Commonwealth of Massachusetts JudyAnn Bigby, MD Secretary Executive Office of Health and Human Services John Auerbach Commissioner Massachusetts Department of Public Health Health of Massachusetts April 2010 Photos in this report are used under a licensing agreement. All other material contained in this report is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without special permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated. Suggested Citation Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Health of Massachusetts. Boston, MA; April 2010. Online To view this report in its entirety or to download specific sections ofHealth of Massachusetts, visit our website at: www.mass.gov/dph/healthofmassachusetts Massachusetts Department of Public Health 250 Washington Street Boston, MA 02108 617.624.6000 www.mass.gov/dph Commonwealth of Massachusetts Deval L. Patrick Governor Commonwealth of Massachusetts Timothy P. Murray Lt. Governor Executive Office of Health and Human Services JudyAnn Bigby, MD Secretary Massachusetts Department of Public Health John Auerbach, MBA Commissioner Table of Contents Preface 6 Homes Special Projects in Hospital Care Emergency Medical Care Policy Perspective: Paula Griswold About Us 12 Chapter 5: Natality and Early Childhood 74 Chapter 1: Demographics and Socio-Economics 16 Births Teen Births Preterm and Low Birthweight Births Population Gender Marital Status Age Race and Multiple Births and -

Hines RFQ Response

Response to VILLAGE OF PORT CHESTER Request for Qualifications Downtown Master Developer September 12, 2017 Table of Contents Page No. 1. Cover Letter 3 2. Information about the Project Team 5 3. Statement of Vision & Approach 8 4. Qualifications & Personnel 10 5. Description of Experience 37 a.Mixed -use, mixed income development 38 b. Public financing and private-public partnerships 47 c. Transit oriented development/new urbanism 48 d. Experience with form-based codes 49 e. Specialized skills 50 6. Experience Working with Spanish-Speaking Communities 55 7. References 57 8. New York Metropolitan Area Presence 59 2 Cover Letter Section 1 September 12, 2017 Eric Zamft, AICP, Director of Planning & Economic Development Janusz Richards, Village Clerk Village of Port Chester 222 Grace Church Street Port Chester, NY 10573 Dear Mr. Zamft and Mr. Richards, Hines Interest Limited Partnership (“Hines”) is pleased to present this Statement of Qualifications in support of our bid to be selected as the Master Developer for Downtown Port Chester, New York. This comprehensive and large-scale project presents substantial opportunities for long-term value generation and neighborhood revitalization and we look forward to potentially working alongside the Port Chester community. Hines has extensive experience in multifaceted and variegated development assignments like this. We are a leading global real estate development, investment and management firm equipped with six decades of global experience working with the public and private sectors through each stage of the planning, design and development process. We believe we are the right firm for this relationship with Port Chester for the following reasons: Hines has a proven track record as a leader in the real estate development industry. -

2014 NCCAA Baseball Mid-East Region Championship-Final.Indd

Mid-East Region BASEBALL CHAMPIONSHIP May 6-9, 2014 Lee University -- Olympic Field cleveland, tennessee Hiwassee College Tigers Johnson University Royals ROSTER... ROSTER... NO. NAME CL. POS. B/T HT. WT. HOMETOWN NO. NAME CL. POS. B/T HT. WT. HOMETOWN 1 Caleb LaJuett Fr. OF/P --- --- --- --- 1 David Mabe --- --- --- --- --- Heiskell, Tennessee 2 Caleb Holt Fr. P --- --- --- --- 3 Brian Cates --- --- --- --- --- Rockford, Tennessee 4 Garrison Sisson Jr. INF --- --- --- --- 4 Sean Finneran --- --- --- --- --- Zebulon, North Carolina Josh Cassidy --- 5 Sr. INF --- --- --- 5 Gavin Gill --- --- --- --- --- Maryville, Tennessee 6 Matt Taylor So. INF/P --- --- --- --- 7 Ian Wymer --- --- --- --- --- Papilon, Nebraska 7 Cody Armstrong Jr. OF/P --- --- --- --- HEAD COACH HEAD COACH 9 Ty Myers --- --- --- --- --- Knoxville, Tennessee 8 Nikk Craig Jr. INF --- --- --- --- HANE ARDNER EN AIR Brad Bales Corryton, Tennessee 9 Mark Christy Fr. OF --- --- --- --- S G B F 11 --- --- --- --- --- 10 Josh Miller So. C --- --- --- --- 12 Garrett Crawford --- --- --- --- --- Levels, West Virginia 11 Ta-Li Martin Jr. OF/1B --- --- --- --- HIWASSEE COLLEGE: JOHNSON UNIVERSITY: 14 Rob Harlamert --- --- --- --- --- Lexington, Kentucky 12 Tyler Butler Fr. P --- --- --- --- Location: ......... Madisonville, Tenn. Location: ..............Knoxville, Tenn. 15 Adrian Thompson --- --- --- --- --- Knoxville, Tennessee 16 Dalton Harrelson So. OF --- --- --- --- Founded: .............................1849 Founded: .............................1893 16 Nate Howard --- ---