The Thought of Liu Shaoqi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

April 28, 1969 Mao Zedong's Speech At

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified April 28, 1969 Mao Zedong’s Speech at the First Plenary Session of the CCP’s Ninth Central Committee Citation: “Mao Zedong’s Speech at the First Plenary Session of the CCP’s Ninth Central Committee,” April 28, 1969, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong wengao, vol. 13, pp. 35-41. Translated for CWIHP by Chen Jian. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/117145 Summary: Mao speaks about the importance of a united socialist China, remaining strong amongst international powers. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation What I am going to say is what I have said before, which you all know, and I am not going to say anything new. Simply I am going to talk about unity. The purpose of unity is to pursue even greater victory. Now the Soviet revisionists attack us. Some broadcast reports by Tass, the materials prepared by Wang Ming,[i] and the lengthy essay in Kommunist all attack us, claiming that our Party is no longer one of the proletariat and calling it a “petit-bourgeois party.” They claim that what we are doing is the imposition of a monolithic order and that we have returned to the old years of the base areas. What they mean is that we have retrogressed. What is a monolithic order? According to them, it is a military-bureaucratic system. Using a Japanese term, this is a “system.” In the words used by the Soviets, this is called “military-bureaucratic dictatorship.” They look at our list of names, and find many military men, and they call it “military.”[ii] As for “bureaucratic,” probably they mean a batch of “bureaucrats,” including myself, [Zhou] Enlai, Kang Sheng, and Chen Boda.[iii] All in all, those of you who do not belong to the military belong to this “bureaucratic” system. -

September 04, 1954 Chinese Foreign Ministry Intelligence Department Report on the Asian-African Conference

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September 04, 1954 Chinese Foreign Ministry Intelligence Department Report on the Asian-African Conference Citation: “Chinese Foreign Ministry Intelligence Department Report on the Asian-African Conference,” September 04, 1954, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, PRC FMA 207-00085-19, 150-153. Obtained by Amitav Acharya and translated by Yang Shanhou. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112440 Summary: The Chinese Foreign Ministry reported Indonesia’s intention to hold the Asian-African Conference, its attitude towards the Asian-African Conference, and the possible development of the Conference. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Secret Compiled by the Intelligence Department of the Foreign Ministry (1) At the end of 1953 when Ceylon proposed to convene the Asian Prime Ministers’ Conference in Colombo, Indonesia expressed its hope of expanding the scope of the conference, including African countries. In January this year, the Indonesian Prime Minister Ali accepted the invitation to participate in the Colombo Five States’ Conference while stating that the Asian-African Conference should be listed in the agenda. (Note: During the period of the Korean War, the Asian Arab Group in the UN was rather active, which probably inspired Indonesia to put forward this proposal.) The Indonesian Foreign Minister Soenarjo believed that the Colombo Conference was the springboard to the Asian-African Conference. Ali proposed to convene the Asian-African Conference at the first day meeting of the Colombo Conference (April 28), but he didn’t get definite support or a resolution from the conference. -

January 14, 1950 Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified January 14, 1950 Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu Citation: “Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu,” January 14, 1950, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian yanjiushi, ed., Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong wengao (Mao Zedong’s Manuscripts since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China), vol. 1 (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 1987), 237; translation from Shuguang Zhang and Jian Chen, eds.,Chinese Communist Foreign Policy and the Cold War in Asia: New Documentary Evidence, 1944-1950 (Chicago: Imprint Publications, 1996), 137. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112672 Summary: Mao Zedong gives instructions to Hu Qiaomu on how to write about recent developments within the Japanese Communist Party. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document [...] Comrade [Hu] Qiaomu: I shall leave for Leningrad today at 9:00 p.m. and will not be back for three days. I have not yet received the draft of the Renmin ribao ["People's Daily"] editorial and the resolution of the Japanese Communist Party's Politburo. If you prefer to let me read them, I will not be able to give you my response until the 17th. You may prefer to publish the editorial after Comrade [Liu] Shaoqi has read them. Out party should express its opinion by supporting the Cominform bulletin's criticism of Nosaka and addressing our disappointment over the Japanese Communist Party Politburo's failure to accept the criticism. It is hoped that the Japanese Communist Party will take appropriate steps to correct Nosaka's mistakes. -

CONTEMPORARY CHINA: a BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R Margins 0.9") by Lynn White

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R margins 0.9") by Lynn White This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of the seminars WWS 576a/Pol. 536 on "Chinese Development" and Pol. 535 on "Chinese Politics," as well as the undergraduate lecture course, Pol. 362; --to provide graduate students with a list that can help their study for comprehensive exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not too much should be made of this, because some such books may be too old for students' purposes or the subjects may not be central to present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan. Students with specific research topics should definitely meet Laird Klingler, who is WWS Librarian and the world's most constructive wizard. This list cannot cover articles, but computer databases can. Rosemary Little and Mary George at Firestone are also enormously helpful. Especially for materials in Chinese, so is Martin Heijdra in Gest Library (Palmer Hall; enter up the staircase near the "hyphen" with Jones Hall). Other local resources are at institutes run by Chen Yizi and Liu Binyan (for current numbers, ask at EAS, 8-4276). Professional bibliographers are the most neglected major academic resource at Princeton. -

Oppression, Dialogue, Body and Emotion – Reading a Many-Splendoured Thing

Linköping university - Department of Culture and Society (IKOS) Master´s Thesis, 30 Credits – MA in Ethnic and Migration Studies (EMS) ISRN: LiU-IKOS/EMS-A--21/02--SE Oppression, Dialogue, Body and Emotion – Reading A Many-Splendoured Thing Yulin Jin Supervisor: Stefan Jonsson Table of Contents 1.Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 1.1 Background……………………………………………………………………………………1 1.2 Research significance and research questions…………………………………………………4 1.3 Literature review………………………………………………………………………………4 1.3.1 Western research on Han Suyin’s life and works and A Many-Splendoured Thing……….5 1.3.2 Domestic research on Han Suyin’s life and works……………………………………….5 1.3.3 Domestic research on A Many-Splendoured Thing……………………………………………7 1.4 Research methods…………………………………………………………………………….9 1.5 Theoretical framework……………………………………………………………………….10 1.5.1 Identity process theory…………………………………………………….……………10 1.5.2 Intersectional theory and multilayered theory …………………………….……………10 1.5.3 Hybridity and the third space theory…………………………………………………….11 1.5.4 Polyphony theory………………………………………………………………………..11 1.5.5 Femininity and admittance………………………………………………………………12 1.5.6 Spatial theories…………………………………………………………………………..13 1.5.7 Body phenomenology……………………………………………………………………14 1.5.8 Hierarchy of needs……………………………………………………………………….15 2. Racial Angle……………………………………………………………………..16 2.1 Economic and emotional oppression…………………………………………………………16 2.2 Eurasian voices and native Chinese consciousnesses……………….………………………20 2.3 Personal solution……………………………………………………….……………………23 2.4 Cultural -

New China and Its Qiaowu: the Political Economy of Overseas Chinese Policy in the People’S Republic of China, 1949–1959

1 The London School of Economics and Political Science New China and its Qiaowu: The Political Economy of Overseas Chinese policy in the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1959 Jin Li Lim A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2016. 2 Declaration: I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98,700 words. 3 Abstract: This thesis examines qiaowu [Overseas Chinese affairs] policies during the PRC’s first decade, and it argues that the CCP-controlled party-state’s approach to the governance of the huaqiao [Overseas Chinese] and their affairs was fundamentally a political economy. This was at base, a function of perceived huaqiao economic utility, especially for what their remittances offered to China’s foreign reserves, and hence the party-state’s qiaowu approach was a political practice to secure that economic utility. -

China's Dual Circulation Economy

THE SHRINKING MARGINS FOR DEBATE OCTOBER 2020 Introduction François Godement This issue of China Trends started with a question. What policy issues are still debated in today’s PRC media? Our able editor looked into diff erent directions for critical voices, and as a result, the issue covers three diff erent topics. The “dual circulation economy” leads to an important but abstruse discussion on the balance between China’s outward-oriented economy and its domestic, more indigenous components and policies. Innovation, today’s buzzword in China, generates many discussions around the obstacles to reaching the country’s ambitious goals in terms of technological breakthroughs and industrial and scientifi c applications. But the third theme is political, and about the life of the Communist Party: two-faced individuals or factions. Perhaps very tellingly, it contains a massive warning against doubting or privately minimizing the offi cial dogma and norms of behavior: “two-faced individuals” now have to face the rise of campaigns, slogans and direct accusations that target them as such. In itself, the rise of this broad type of accusation demonstrates the limits and the dangers of any debate that can be interpreted as a questioning of the Party line, of the Centre, and of its core – China’s paramount leader (领袖) Xi Jinping. The balance matters: between surviving policy debates on economic governance issues and what is becoming an all-out attack that targets hidden Western political dissent, doubts or non-compliance beyond any explicit form of debate. Both the pre-1949 CCP and Maoist China had so-called “line debates” which science has seen this often turned into “line struggles (路线斗争)”: the offi cial history of the mostly as a “fragmented pre-1966 CCP, no longer reprinted, listed nine such events. -

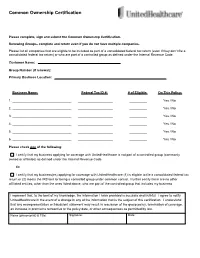

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11