Bishop Stephen Tempier and Thomas Aquinas : a Separate Process Against Aquinas?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tables of Contemporary Chronology, from the Creation to A. D. 1825

: TABLES OP CONTEMPORARY CHUONOLOGY. FROM THE CREATION, TO A. D. 1825. \> IN SEVEN PARTS. "Remember the days of old—consider the years of many generations." 3lorttatttt PUBLISHED BY SHIRLEY & HYDE. 1629. : : DISTRICT OF MAItfE, TO WIT DISTRICT CLERKS OFFICE. BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the first day of June, A. D. 1829, and in the fifty-third year of the Independence of the United States of America, Messrs. Shiraey tt Hyde, of said District, have deposited in this office, the title of a book, the right whereof they claim as proprietors, in the words following, to wit Tables of Contemporary Chronology, from the Creation, to A.D. 1825. In seven parts. "Remember the days of old—consider the years of many generations." In conformity to the act of the Congress of the United States, entitled " An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned ;" and also to an act, entitled "An Act supplementary to an act, entitled An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned ; and for extending the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints." J. MUSSEV, Clerk of the District of Maine. A true copy as of record, Attest. J MUSSEY. Clerk D. C. of Maine — TO THE PUBLIC. The compiler of these Tables has long considered a work of this sort a desideratum. -

The Thirteenth Century

1 SHORT HISTORY OF THE ORDER OF THE SERVANTS OF MARY V. Benassi - O. J. Diaz - F. M. Faustini Chapter I THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY From the origins of the Order (ca. 1233) to its approval (1304) The approval of the Order. In the year 1233... Florence in the first half of the thirteenth century. The beginnings at Cafaggio and the retreat to Monte Senario. From Monte Senario into the world. The generalate of St. Philip Benizi. Servite life in the Florentine priory of St. Mary of Cafaggio in the years 1286 to 1289. The approval of the Order On 11 February 1304, the Dominican Pope Benedict XI, then in the first year of his pontificate, sent a bull, beginning with the words Dum levamus, from his palace of the Lateran in Rome to the prior general and all priors and friars of the Order of the Servants of Saint Mary. With this, he gave approval to the Rule and Constitutions they professed, and thus to the Order of the Servants of Saint Mary which had originated in Florence some seventy years previously. For the Servants of Saint Mary a long period of waiting had come to an end, and a new era of development began for the young religious institute which had come to take its place among the existing religious orders. The bull, or pontifical letter, of Pope Benedict XI does not say anything about the origins of the Order; it merely recognizes that Servites follow the Rule of St. Augustine and legislation common to other orders embracing the same Rule. -

Index Nominum

Index Nominum Abualcasim, 50 Alfred of Sareshal, 319n Achillini, Alessandro, 179, 294–95 Algazali, 52n Adalbertus Ranconis de Ericinio, Ali, Ismail, 8n, 132 205n Alkindi, 304 Adam, 313 Allan, Mowbray, 276n Adam of Papenhoven, 222n Alne, Robert, 208n Adamson, Melitta Weiss, 136n Alonso, Manual, 46 Adenulf of Anagni, 301, 384 Alphonse of Poitiers, 193, 234 Adrian IV, pope, 108 Alverny, Marie-Thérèse d’, 35, 46, Afonso I Henriques, king of Portu- 50, 53n, 93, 147, 177, 264n, 303, gal, 35 308n Aimery, archdeacon of Tripoli, Alvicinus de Cremona, 368 105–6 Amadaeus VIII, duke of Savoy, Alberic of Trois Fontaines, 100–101 231 Albert de Robertis, bishop of Ambrose, 289 Tripoli, 106 Anastasius IV, pope, 108 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Anti- Anatoli, Jacob, 113 och, 73, 77n, 86–87, 105–6, 122, Andreas the Jew, 116 140 Andrew of Cornwall, 201n Albert of Schmidmüln, 215n, 269 Andrew of Sens, 199, 200–202 Albertus Magnus, 1, 174, 185, 191, Antonius de Colell, 268 194, 212n, 227, 229, 231, 245–48, Antweiler, Wolfgang, 70n, 74n, 77n, 250–51, 271, 284, 298, 303, 310, 105n, 106 315–16, 332 Aquinas, Thomas, 114, 256, 258, Albohali, 46, 53, 56 280n, 298, 315, 317 Albrecht I, duke of Austria, 254–55 Aratus, 41 Albumasar, 36, 45, 50, 55, 59, Aristippus, Henry, 91, 329 304 Arnald of Villanova, 1, 156, 229, 235, Alcabitius, 51, 56 267 Alderotti, Taddeo, 186 Arnaud of Verdale, 211n, 268 Alexander III, pope, 65, 150 Ashraf, al-, 139n Alexander IV, pope, 82 Augustine (of Hippo), 331 Alexander of Aphrodisias, 311, Augustine of Trent, 231 336–37 Aulus Gellius, -

Beyond the Letter of His Master's Thought : CNR Mccoy on Medieval

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Érudit Article "Beyond the Letter of His Master’s Thought : C.N.R. McCoy on Medieval Political Theory" William P.Haggerty Laval théologique et philosophique, vol. 64, n° 2, 2008, p. 467-483. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/019510ar DOI: 10.7202/019510ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 10 février 2017 10:01 Laval théologique et philosophique, 64, 2 (juin 2008) : 467-483 BEYOND THE LETTER OF HIS MASTER’S THOUGHT : C.N.R. MCCOY ON MEDIEVAL POLITICAL THEORY William P. Haggerty Department of Philosophy Gannon University, Erie, Pennsylvania RÉSUMÉ : Publié en 1962, le livre de Charles N.R. McCoy, intitulé The Structure of Political Thought, demeure un travail important, encore qu’oublié, sur l’histoire de la philosophie poli- tique. Bien que l’ouvrage ait reçu de bonnes appréciations, il n’existe pas encore d’examen critique de son traitement de la théorie politique médiévale. -

Justifying Religious Freedom: the Western Tradition

Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition E. Gregory Wallace* Table of Contents I. THESIS: REDISCOVERING THE RELIGIOUS JUSTIFICATIONS FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM.......................................................... 488 II. THE ORIGINS OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN EARLY CHRISTIAN THOUGHT ................................................................................... 495 A. Early Christian Views on Religious Toleration and Freedom.............................................................................. 495 1. Early Christian Teaching on Church and State............. 496 2. Persecution in the Early Roman Empire....................... 499 3. Tertullian’s Call for Religious Freedom ....................... 502 B. Christianity and Religious Freedom in the Constantinian Empire ................................................................................ 504 C. The Rise of Intolerance in Christendom ............................. 510 1. The Beginnings of Christian Intolerance ...................... 510 2. The Causes of Christian Intolerance ............................. 512 D. Opposition to State Persecution in Early Christendom...... 516 E. Augustine’s Theory of Persecution..................................... 518 F. Church-State Boundaries in Early Christendom................ 526 G. Emerging Principles of Religious Freedom........................ 528 III. THE PRESERVATION OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN MEDIEVAL AND REFORMATION EUROPE...................................................... 530 A. Persecution and Opposition in the Medieval -

Light in the Dark Places: Or, Memorial of Christian Life in the Middle Ages

Light in the Dark Places: or, Memorial of Christian Life in the Middle Ages. Author(s): Neander, Augustus (1789-1850) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Augustus Neander began his religious studies in speculative theory, but his changing interests led him to the study of church history. In his book, Light in the Dark Places, Neander©s talent as a writer and a historian is tremendously evident; collected within this volume is an abundance of re- markable information about church history. Neander shares information about the lives of Christian individuals and com- munities during times of darkness and of triumph. Neander also reveals unknown facts about early missionaries and martyrs of the church. This historical analysis will provide today©s Christians with insight into the church©s elaborate past, so that they may learn from previous mistakes and embrace habits of righteousness. Emmalon Davis CCEL Staff Writer i Contents Title Page 1 Prefatory Material 2 Preface to the American Edition. 2 Preface. 3 Contents. 4 Part I. Operations of Christianity During and After the Confusion Produced by the 6 Irruption of the Barbarians. Introduction 7 The North African Church Under the Vandals. 8 Everinus in Germany. 19 Labours of Pious Men in France. 26 Germanus of Auxerre (Antistodorum). 27 Lupus of Troyes. 29 Cæsarius of Arles. 30 Epiphanius of Pavia. 49 Eligius, Bishop of Noyon. 50 The Abbots Euroul and Loumon. 58 Gregory the Great, Bishop of Rome. 59 Christianity in Poverty and Lowliness, and on the Sick Bed. 72 Part II. Memoirs from the History of Missions in the Middle Ages. -

Belief in History Innovative Approaches to European and American Religion

Belief in History Innovative Approaches to European and American Religion Editor Thomas Kselman UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME PRESS NOTRE DAME LONDON Co1 Copyright © 1991 by University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 Ackn< All Rights Reserved Contr Manufactured in the United States of America Introc 1. Fai JoJ 2. Bo Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hi; 3. Alt Belief in history : innovative approaches to European and American religion I editor, Thomas Kselman. Th p. em. 4. "H Includes bibliographical references. anc ISBN 0-268-00687-3 1. Europe-Religion. 2. United States-Religion. I. 19: Kselman, Thomas A. (Thomas Albert), 1948- BL689.B45 1991 90-70862 270-dc20 CIP 5. Th Pat 6. Th of Sta 7. Un JoA 8. Hi~ Arr Bodily Miracles in the High Middle Ages 69 many modern historians) have reduced the history of the body to the history of sexuality or misogyny and have taken the opportunity to gig gle pruriently or gasp with horror at the unenlightened centuries be 2 fore the modern ones. 7 Although clearly identified with the new topic, this essay is none Bodily Miracles and the Resurrection theless intended to argue that there is a different vantage point and a of the Body in the High Middle Ages very different kind of material available for writing the history of the body. Medieval stories and sermons did articulate misogyny, to be sure;8 doctors, lawyers, and theologians did discuss the use and abuse of sex. 9 Caroline Walker Bynum But for every reference in medieval treatises to the immorality of con traception or to the inappropriateness of certain sexual positions or to the female body as temptation, there are dozens of discussions both of body (especially female body) as manifestation of the divine or demonic "The body" has been a popular topic recently for historians of and of technical questions generated by the doctrine of the body's resur Western European culture, especially for what we might call the Berkeley rection. -

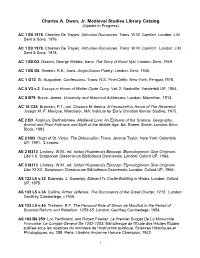

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

Medieval Discussions of Property

Imprint Academic Ltd. MEDIEVAL DISCUSSIONS OF PROPERTY: "RATIO" AND "DOMINIUM" ACCORDING TO JOHN OF PARIS AND MARSILIUS OF PADUA Author(s): Janet Coleman Source: History of Political Thought, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Summer 1983), pp. 209-228 Published by: Imprint Academic Ltd. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26212443 Accessed: 23-11-2018 18:56 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Imprint Academic Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History of Political Thought This content downloaded from 128.59.242.126 on Fri, 23 Nov 2018 18:56:30 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms MEDIEVAL DISCUSSIONS OF PROPERTY: RATIO AND DOMINIUM ACCORDING TO JOHN OF PARIS AND MARSILIUS OF PADUA Janet Coleman It is well known that John of Paris was a major publicist who, at the turn of the fourteenth century, offered his contribution to the debate over the boun daries of sovereignty. This was a debate that had taken a particularly vicious and explosive turn in the polemic between Philip the Fair and Boniface VIII. John of Paris's De Potestate Regia et Papali is taken to be a via media in the then current argument over sacerdotal and royal power, a debate that had in one way or another been a continuous part of the political scenario through out the middle ages. -

29, 2015 Holy Week & Easter Schedule 2015

Interfaith Airport Chapels of Chicago Chicago Midway and O’Hare International Airports P.O. Box 66353 ●Chicago, Illinois 60666-0353 ●(773) 686-AMEN (2636) ●www.airportchapels.org Week of March 29, 2015 HOLY WEEK & EASTER SCHEDULE 2015 WELCOME TO THE INTERFAITH AIRPORT CHAPELS OF CHICAGO! Saturday, March 28—Palm Sunday Vigil The O’Hare Airport Chapel and Midway Airport Protestant Worship Chapel are each a peaceful oasis in a busy venue. A 10:00 a.m., 12:00 & 1:30 p.m. place to bow your head in prayer while lifting up Catholic Masses your heart and spirit! Prayer books and rugs, rosa- 4:00 & 6:00 p.m. — ORD ries, and worship materials are available, as are 4:00 p.m. — MDW chaplains for spiritual counsel. You are welcome to ❧ attend Mass or Worship services and to come to the Sunday, March 29 – PALM SUNDAY chapels (open 24/7) to pray or meditate. Catholic Masses May God bless your travels. 6:30, 9:00, 11:00 a.m. & 1:00 p.m. — ORD — Fr. Michael Zaniolo, Administrator 9:00 & 11:00 a.m. — MDW Protestant Worship HAPEL IRTHDAYS NNIVERSARIES C B & A 10:00 a.m. & 12:00 p.m. — ORD 10:00 a.m., 12:00 & 1:30 p.m. — MDW ✈ Birthday blessings & best wishes go out to Mrs. Lynn Busiedlik ❧ today, March 29 and to Ms. Marie Higgins April 3. WEEKDAYS OF HOLY WEEK Monday, March 30 at 11:30 a.m. - ORD & MDW - Catholic Mass INTERFAITH CALENDAR & EVENTS Tuesday, March 31 at 11:30 a.m. -

Download Download

Prophetic Parables and Philosophic Falsehoods Samuel Scolnicov In memoriam The writings of Arisotle’s teacher Plato are in parables and hard to understand. One can dispense with them, for the writings of Arisotle suffice and we need not occupy [our attention] with writings of earlier [philosophers]. * So writes Maimonides to Ibn Tibbon, the translator of the Guide o f the Per plexed into Hebrew. Aristotle’s works, he says, are ‘the roots and foundations of all work on the sciences’ and all that preceded him were (as indeed Aristotle himself saw them) conducive to him and superseded by him. Indeed, Plato was read — even when directly and not mediated by commentaries and epitomes — through Aristotle. Alfarabi, conspicuously, writes his Agreement of Plato and Aristotle. But even those who recognized the difference between them still un derstood Plato in essential respects as an Aristotelian. This is nowhere as evident — and as distorting — as in the Aristotelization of Plato’s epistemology. But more on this presently. On the other hand, it is commonplace that Platonic political philosophy, with its clear normative orientation, was much more congenial to religious thought than Aristotle’s rather more descriptive and analytical approach. The prophet, Moses or Muhammad,2 is he who establishes the political order divinely sanc tioned and henceforth entrusted to the religious establishment. And so it is that here, by contrast, Aristotle is unwittingly assimilated to Plato, to the extent that Averroes in his Commentary on the Republic can confidently present Plato’s political philosophy as doing duty for Aristotle’s, which he did not know first hand.3 In Christianity, this Platonization of political thought is made more difficult by Jesus’ dissociation of religion from political power: ‘Render unto Caesar the Letter of Maimonides to Samuel Ibn Tibbon.