Lost in Transition: from Post-Network to Post-Television1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Press Release

Elisabeth Moss as Peggy Olson Outstanding Lead Actor In A Drama Series Nashville • ABC • ABC Studios Connie Britton as Rayna James Breaking Bad • AMC • Sony Pictures Television Scandal • ABC • ABC Studios Bryan Cranston as Walter White Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope Downton Abbey • PBS • A Carnival / Masterpiece Co-Production Hugh Bonneville as Robert, Earl of Grantham Outstanding Lead Actor In A Homeland • Showtime • Showtime Presents, Miniseries Or A Movie Teakwood Lane Productions, Cherry Pie Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Keshet, Fox 21 Weintraub Productions in association with Damian Lewis as Nicholas Brody HBO Films House Of Cards • Netflix • Michael Douglas as Liberace Donen/Fincher/Roth and Trigger Street Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Inc. in association with Media Weintraub Productions in association with Rights Capital for Netflix HBO Films Kevin Spacey as Francis Underwood Matt Damon as Scott Thorson Mad Men • AMC • Lionsgate Television The Girl • HBO • Warner Bros. Jon Hamm as Don Draper Entertainment, GmbH/Moonlighting and BBC in association with HBO Films and Wall to The Newsroom • HBO • HBO Entertainment Wall Media Jeff Daniels as Will McAvoy Toby Jones as Alfred Hitchcock Parade's End • HBO • A Mammoth Screen Production, Trademark Films, BBC Outstanding Lead Actress In A Worldwide and Lookout Point in association Drama Series with HBO Miniseries and the BBC Benedict Cumberbatch as Christopher Tietjens Bates Motel • A&E • Universal Television, Carlton Cuse Productions and Kerry Ehrin -

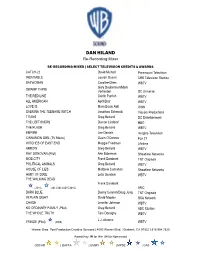

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS CATCH-22 David Michod Paramount Television INSATIABLE Lauren Gussis CBS Television Studios BATWOMAN Caroline Dries WBTV Gary Dauberman/Mark SWAMP THING Verheiden DC Universe THE RED LINE Cairlin Parrish WBTV ALL AMERICAN April Blair WBTV LOVE IS Mara Brock Akil OWN SABRINA THE TEENAGE WITCH Jonathan Schmock Viacom Productions TITANS Greg Berlanti DC Entertainment THE LEFTOVERS Damon Lindelof HBO THE FLASH Greg Berlanti WBTV EMPIRE Lee Daniels Imagine Television CINNAMON GIRL (TV Movie) Gavin O'Connor Fox 21 WITCHES OF EAST END Maggie Friedman Lifetime ARROW Greg Berlanti WBTV RAY DONOVAN (Pilot) Ann Biderman Showtime Networks MOB CITY Frank Darabont TNT Originals POLITICAL ANIMALS Greg Berlanti WBTV HOUSE OF LIES Matthew Carnahan Showtime Networks HART OF DIXIE Leila Gerstein WBTV THE WALKING DEAD Frank Darabont (2010) (2012/2014/2015/2016) AMC DARK BLUE Danny Cannon/Doug Jung TNT Originals IN PLAIN SIGHT David Maples USA Network CHASE Jennifer Johnson WBTV NO ORDINARY FAMILY (Pilot) Greg Berlanti ABC Studios THE WHOLE TRUTH Tom Donaghy WBTV J.J. Abrams FRINGE (Pilot) (2009) WBTV Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.7825 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS LIMELIGHT (Pilot) David Semel, WBTV HUMAN TARGET Jonathan E. Steinberg WBTV EASTWICK Maggie Friedman WBTV V (Pilot) Kenneth Johnson WBTV TERMINATOR: THE SARAH CONNER Josh Friedman CHRONICLES WBTV CAPTAIN -

SAG/AFTRA FILM (Partial List) Scare Package Supporting/ “Officer Ragen” Paper Street Pictures/ Aaron B. Koontz Dir. Human Pl

SAG/AFTRA FILM (Partial List) Scare Package Supporting/ “Officer Ragen” Paper Street Pictures/ Aaron B. Koontz Dir. Human Play Lead/ “James” Paper Street Pictures/ Mathieu Ricordi Dir. Little Woods Supporting/ "Man" Buffalo Picture House/ Nia DaCosta Dir. Elephone Man Lead/ "Bobby" Global Films/ Magarditch Halvadjian Dir. The Cable Men Starring/ "Barney" McShane Films/ Robin Conly Dir. Bitch (Short) Supporting/ "Will" Edgen Films/ Robin Conly Dir. Small Packages (Short) Starring/ "Porter" Grade A Films/ Anthony Faust Dir. An American In Texas Lead/ "Earl Doonan" Film Exchange/ Anthony Pedone Dir. Overcast (Short) Lead/ "Paulie" Atomic Productions/ Ben Adams Dir. Bomb City Supporting/ "Officer Chuck" 3rd Identity Films/ Jamie Brooks Dir. As Far As The Eye Can See Supporting/ "Bob Tanner" AFATECS LLC/ David Franklin Dir. Entity Starring/ "Eugene" Screengage LLC/ Michael Yurinko Dir. Human Play Lead/ "James" Paper Street Pictures/ Mathieu Ricordi Dir. Hard Reset 3-D Lead/ "Det. Wright" Buk Films/ Deepak Chetty Dir. The Doo Dah Man Supporting/ "Frank" Flatiron Pictures/ Claude Green Dir. Adventures of Pepper and Paula Lead/ "Ricky" The Nations/ Kevin & Robin Nations Dir. Sin City 2 Supporting/ "Tourist" Troublemaker/ Robert Rodriguez Dir. TELEVISION The Pact (Mini Series) Lead/ ”Drummer” Katara Studios/ Michael Phillips EP. Three Knee Deep (Mini Series) Lead/ "Jack" Luna/Luca Bercovichi Dir. The Leftovers Recurring/ "Sam" HBO/ Damon Lindelof EP. Queen of the South Co-Star/ "Donald Henry" USA/ Matthew Penn EP. From Dusk Til Dawn Co-Star/ "Chester" El Rey/ Eduardo Sanchez Dir. In An Instant Starring/ "Pete Soulis" ABC/ Todd Cobery Dir. American Crime Co-Star/ "Patrol Officer" ABC/ John Ridley Dir. -

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Henley's the Wake of Jamie Foster and the Miss Firecracker Contest

‘SNOW BRIDE’ CAST BIOS PATRICIA RICHARDSON (Maggie Tannenhill) – Patricia Richardson is best known for her portrayal of Jill Taylor on the long running series “Home Improvement” in which she co-starred with Tim Allen. For her work on the series, she received four Emmy® nominations and two Golden Globe® nominations as Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series. While performing in “Home Improvement,” she also co-hosted the Emmy® Awards with Ellen DeGeneres. In 2009, the cast members of “Home Improvement” received a Fan Favorite Award from the TV Land Awards. She has also received a Vision Award and a Women In Film Award in Texas and commendations from the Prism Awards for her work in the show. For two years, she had a recurring role in “The West Wing” as Sheila Brooks, Sen. Arnold Vinick’s (Alan Alda) chief of staff. She was nominated for an Independent Spirit Award for her role in “Ulee’s Gold,” opposite Peter Fonda and directed by Victor Nunez. Previously, Richardson garnered rave reviews for her portrayal of Marilyn Monroe’s mother in the CBS miniseries “Blonde.” She played twins in “Viva Las Nowhere,” co-starring Danny Stern and James Caan, which was released on video under the title “Dead Simple” and won a Seattle Film Festival Award. She received more great reviews for her role in Lifetime’s “Sophie & the Moonhanger,” co-starring Lynn Whitfield and Jason Bernard and “Undue Influence,” with Brian Dennehy. Other films include “Lost Angels,” “In Country” and “Beautiful Wave.” She was brought out to Los Angeles from New York after several years of doing theater, first by Norman Lear and then Alan Burns, to do three different series prior to “Home Improvement” - “Double Trouble” for Lear and then “Eisenhower and Lutz” and “FM” for Burns. -

Coldplay? 2016 CILL Season Begins 2016 Primary Election Results: So Goes City Island

Periodicals Paid at Bronx, N.Y. USPS 114-590 Volume 45 Number 4 May 2016 One Dollar Coldplay? 2016 CILL Season Begins By VIRGINIA DANNEGGER and KAREN NANI ria Piri, concession stand managers Jim and singlehandedly did the job of several and Sue Goonan, and equipment manager people. Even though his boys aged out of Lou Lomanaco. Several of these board the league, John still dedicates his time to members have served multiple terms on the help.” He presented John with a framed board. CILL jersey and a plaque in appreciation Mr. Esposito gave special thanks to for his support of the league and the City Photos by RICK DeWITT the outgoing president, John Tomsen, Island community. It was a chilly start to the 2016 Little League season on April 9, but the baseball tradi- who threw out the first pitch. “John has “As many of you know, volunteering tion dating back to 1900 is alive and warm on City Island. There are major, minor and time is a family commitment. Whether it t-ball teams competing once again this season. The ceremonial first pitch was thrown been president of the CILL since 2009 by outgoing president John Tomsen, who was also awarded a framed jersey by the Continued on page 19 new league president, Dom Esposito (right, top photo). New York State Assemblyman Michael Benedetto joined Catherine Ambrosini, Mr. Esposito and Mr. Tomsen (second photo, l. to r.) for the season opener. The American Legion color guard bearers led the teams in the “Star Spangled Banner.” As the weather warms up, head down to Ambro- 2016 Primary Election Results: sini Field next to P.S. -

LOST "Raised by Another" (YELLOW) 9/23/04

LOST “Raised by Another” CAST LIST BOONE................................Ian Somerhalder CHARLIE..............................Dominic Monaghan CLAIRE...............................Emilie de Ravin HURLEY...............................Jorge Garcia JACK.................................Matthew Fox JIN..................................Daniel Dae Kim KATE.................................Evangeline Lilly LOCKE................................Terry O’Quinn MICHAEL..............................Harold Perrineau SAWYER...............................Josh Holloway SAYID................................Naveen Andrews SHANNON..............................Maggie Grace SUN..................................Yunjin Kim WALT.................................Malcolm David Kelley THOMAS............................... RACHEL............................... MALKIN............................... ETHAN................................ SLAVITT.............................. ARLENE............................... SCOTT................................ * STEVE................................ * www.pressexecute.com LOST "Raised by Another" (YELLOW) 9/23/04 LOST “Raised by Another” SET LIST INTERIORS THE VALLEY - Late Afternoon/Sunset CLAIRE’S CUBBY - Night/Dusk/Day ENTRANCE * ROCK WALL - Dusk/Night/Day * INFIRMARY CAVE - Morning JACK’S CAVE - Night * LOFT - Day - FLASHBACK MALKIN’S HOUSE - Day - FLASHBACK BEDROOM - Night - FLASHBACK LAW OFFICES CONFERENCE ROOM - Day - FLASHBACK EXTERIORS JUNGLE - Night/Day ELSEWHERE - Day CLEARING - Day BEACH - Day OPEN JUNGLE - Morning * SAWYER’S -

„When Am I?“ – Zeitlichkeit in Der US-Serie LOST, Teil 2

GABRIELE SCHABACHER „When Am I?“ – Zeitlichkeit in der US-Serie LOST, Teil 2 Previously on … An der US-Serie LOST lässt sich eine systematische Nutzung der temporalen Di- mension beobachten: Auf den Ebenen von Erzählzeit und erzählter Zeit – das konnte der erste Teil dieses Beitrags zeigen – ist der Einsatz von story arcs überspan- nenden Flashbacks bzw. Flashforwards sowie eine handlungsseitig ausgeführte Thematisierung und Problematisierung von Zeitreisen und Teleportation für das Seriennarrativ zentral. Schon diese zeitlichen Relationen ermöglichen der Narra- tion entscheidende Inversionen und paradoxe Konstruktionen, die für die Serie LOST charakteristisch geworden sind. 1. Die dritte Zeit Eine dritte Dimension der Narration, um die es dem zweiten Teil dieses Beitrags geht, lässt sich nun keiner der beiden bisher thematisierten Gruppen eindeutig zuordnen, weder also der Erzählzeit und damit den stilistischen Mitteln im engeren Sinne, noch der erzählten Zeit, d. h. der inhaltlichen Ebene der Geschichte. Es handelt sich vielmehr um eine Gruppe von Phänomen, die sich durch eine spezifi - sche Übergängigkeit zwischen diesen beiden Kategorien auszeichnen. Daher wird im Folgenden auf die in der Serie geäußerten Vorahnungen, Time Loops, Bewusst- seinsreisen und Zeitsprünge einzugehen sein, um die Hybridisierung von Stilistik und Inhaltsmomenten der Narration zu verdeutlichen. Das Vorhandensein solcher hybrider Elemente ist es, das eine mögliche Erklärung für die besondere Faszinati- on an LOST und eine spezifi sch temporal motivierte Komplexität -

Yul Kwon, from Bullying Target to Reality TV Star by NPR Staff from Npr.Org 2012

Name: Class: Yul Kwon, From Bullying Target to Reality TV Star By NPR Staff From Npr.Org 2012 Yul Kwon’s early life was mired with a host of challenges. Born to South Korean immigrants in New York, Kwon never had a positive role model from his community. In 2006, he decided to join the cast of Survivor and make a name for himself in popular culture. As you read, take notes on how Yul Kwon overcame his personal demons to become a role model for other Asian Americans. [1] Yul Kwon first earned his game-changer status when the Yale University-trained lawyer put his career on hold to compete on the CBS show Survivor in 2006. He became the first Asian- American to win that show's $1 million prize. That led to work as a special correspondent for CNN, a lecturer at the FBI Academy, and deputy chief of the Federal Communication Commission's Consumer and Governmental Affairs Bureau. Kwon currently hosts the news program LinkAsia on LinkTV, and recently finished hosting PBS' America Revealed, a mini documentary series "Yul J. Kwon" is licensed under CC BY 2.0. about agriculture, transportation, energy and manufacturing. Being A Target Of Bullying Kwon's early life involved a host of challenges. He was born in 1975 in New York to South Korean immigrants. He tells Tell Me More host Michel Martin he had a severe lisp as a kid, so many people assumed he was a foreigner who could not speak English properly. Kwon says he grew increasingly quiet to avoid being teased or beaten up.