Circulating Species of Leishmania at Microclimate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Liste Des Participants Avec Choix Au Mouvement Regulier Pour Mutation Du Personnel Paramedical Annee 2017

LA LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS AVEC CHOIX AU MOUVEMENT REGULIER POUR MUTATION DU PERSONNEL PARAMEDICAL ANNEE 2017 DATE DATE Poste Actuel Choix NOMBRE SCORE SITUATION PROFESSION DATE DE D'AFFECTATION D'AFFECTATION ORDRE DE N Groupe PPR NOM PRENOM SEXE D'ENFANT N Z C national FAMILIALE CONJOINT RECRUTEMENT AU POSTE DANS LA CHOIX DELEGATION FORMATION SANITATIRE DELEGATION FORMATION SANITATIRE S ACTUEL PROVINCE D'ORIGINE D'ORIGINE D'ACCUEIL D'ORIGINE 1 INFIRMIER POLYVALENT 262446 KMICH TALEB 201,1666667 M M 0 Autre 02/01/1984 02/01/1984 02/01/1984 33,8333333 5 3 1 BOULEMANE DR Tirnest BOULEMANE CSU Outat El Haj 2 INFIRMIER POLYVALENT 179704 DAHA OMAR 192,5 M M 6 Autre 01/07/1981 27/06/1987 01/07/1981 36,3333333 4 3 1 TIZNIT DR Lkraima TIZNIT CSCA Sahel 3 INFIRMIER POLYVALENT 867778 BERNICHA FOUZIA 157,6666667 F M 3 Autre 01/07/1982 01/07/1982 01/07/1982 35,3333333 1 2 1 EL JADIDA CSCA Ouled Frej EL JADIDA CSU Al Matar CRSR Centre De Reference de la Sante 4 INFIRMIER POLYVALENT 854836 EL RHAYOUR FATIMA 142,5 F M 5 Autre 01/07/1981 23/10/1992 02/10/1992 25,0833333 3 3 1 MOULAY YACOUB DR Ain Bouali MOULAY YACOUB Reproductive 5 INFIRMIER POLYVALENT 854836 EL RHAYOUR FATIMA 142,5 F M 5 Autre 01/07/1981 23/10/1992 02/10/1992 25,0833333 3 3 2 MOULAY YACOUB DR Ain Bouali MOULAY YACOUB CSCA S. Ahmed Bernoussi 6 INFIRMIER POLYVALENT 262313 DWASSY LHASSAN 136,3333333 M M 2 Autre 02/01/1984 13/10/2015 02/01/1984 33,8333333 4 2 1 TAROUDANT CSC Ait Oussaih TAROUDANT CSU Talmaklate 7 INFIRMIER POLYVALENT 262313 DWASSY LHASSAN 136,3333333 M M 2 Autre 02/01/1984 -

Floristic Analysis of Marmoucha's Plant Diversity (Middle Atlas, Morocco)

LAZAROA 34: 117-140. 2013 doi: 10.5209/rev_LAZA.2013.v34.n1.40753 ISSN: 0210-9778 Floristic analysis of Marmoucha’s plant diversity (Middle Atlas, Morocco) Fatima Nassif & Abbès Tanji (*) Abstract: Nassif, F. & Tanji, A. Floristic analysis of Marmoucha’s plant diversity (Middle Atlas, Morocco). Lazaroa 34: 117-140 (2013). As part of an ethnobotanical exploration among the Berbers of Marmoucha in the Middle Atlas in Morocco, a floristic analysis was conducted to inventory the existing plants and assess the extent of plant diversity in this area. Located in the eastern part of the Middle Atlas, the Marmoucha is characterized by the presence of various ecosystems ranging from oak and juniper forests to high altitude steppes typical from cold areas with thorny plants. The fieldwork was conducted over five years (2008-2012) using surveys and informal techniques. The results show that the number of species recorded in Marmoucha is 508 distributed over 83 families and 325 genera, representing 13%, 54% and 33% of species, families and genera at the national level, respectively. With 92 species, the Asteraceae is the richest family, representing 18% of the total reported followed by Poaceae and the Fabaceae . From a comparative perspective, the ranking of the eight richer families of the local flora in relation to their position in the national flora reveals a significant match between the positions at local and national levels with slight ranking differences except in the case of Rosaceae. In the study area, the number of endemics is significant. It amounts to 43 species and subspecies belonging to 14 families with the Asteraceae counting 10 endemics. -

Cadastre Des Autorisations TPV Page 1 De

Cadastre des autorisations TPV N° N° DATE DE ORIGINE BENEFICIAIRE AUTORISATIO CATEGORIE SERIE ITINERAIRE POINT DEPART POINT DESTINATION DOSSIER SEANCE CT D'AGREMENT N Casablanca - Beni Mellal et retour par Ben Ahmed - Kouribga - Oued Les Héritiers de feu FATHI Mohamed et FATHI Casablanca Beni Mellal 1 V 161 27/04/2006 Transaction 2 A Zem - Boujad Kasbah Tadla Rabia Boujad Casablanca Lundi : Boujaad - Casablanca 1- Oujda - Ahfir - Berkane - Saf Saf - Mellilia Mellilia 2- Oujda - Les Mines de Sidi Sidi Boubker 13 V Les Héritiers de feu MOUMEN Hadj Hmida 902 18/09/2003 Succession 2 A Oujda Boubker Saidia 3- Oujda La plage de Saidia Nador 4- Oujda - Nador 19 V MM. EL IDRISSI Omar et Driss 868 06/07/2005 Transaction 2 et 3 B Casablanca - Souks Casablanca 23 V M. EL HADAD Brahim Ben Mohamed 517 03/07/1974 Succession 2 et 3 A Safi - Souks Safi Mme. Khaddouj Bent Salah 2/24, SALEK Mina 26 V 8/24, et SALEK Jamal Eddine 2/24, EL 55 08/06/1983 Transaction 2 A Casablanca - Settat Casablanca Settat MOUTTAKI Bouchaib et Mustapha 12/24 29 V MM. Les Héritiers de feu EL KAICH Abdelkrim 173 16/02/1988 Succession 3 A Casablanca - Souks Casablanca Fès - Meknès Meknès - Mernissa Meknès - Ghafsai Aouicha Bent Mohamed - LAMBRABET née Fès 30 V 219 27/07/1995 Attribution 2 A Meknès - Sefrou Meknès LABBACI Fatiha et LABBACI Yamina Meknès Meknès - Taza Meknès - Tétouan Meknès - Oujda 31 V M. EL HILALI Abdelahak Ben Mohamed 136 19/09/1972 Attribution A Casablanca - Souks Casablanca 31 V M. -

Direction Regionale Du Centre Nord

ROYAUME DU MAROC Office National de l’Électricité et de l’Eau Potable Branche Eau DIRECTION REGIONALE DU CENTRE NORD ________________________________ Projet de renforcement de la production et d’amélioration de la performance technique et commerciale de l’eau potable (PRPTC) Composante : Programme d’amélioration des performances techniques des centres de la Direction Régionale du Centre Nord PLAN D’ACQUISITION DES TERRAINS ET D’INDEMNISATION DES PERSONNES AFFECTEES PAR LE PROJET (PATI-PAP) FINANCEMENT BAD 15 Août 2021 RESUME EXECUTIF DU PATI-PAP 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. CONTEXTE ET JUSTIFICATION DU PROJET 1.2. OBJECTIFS DU PATI-PAP 1.3. METHODOLOGIE D’ELABORATION DU PATI-PAP 2. DESCRIPTION DU PROJET ET DE LA ZONE CONCERNEE 2.1. Description du projet 2.2. Consistance du projet 2.2.1 Consistance des lots 2.2.2. Besoins en foncier 2.3. Présentation de la zone du projet 2.3.1 Présentation géographique 2.3.2. POPULATION ET DEMOGRAPHIE 2.3.3 Urbanisation 2.3.4 Armature urbaine 2.3.5. INFRASTRUCTURES DE BASE 2.3.6. SECTEURS PRODUCTIFS 2.3.7 CAPITAL IMMATERIEL 3. IMPACTS POTENTIELS DU PROJET 3.1. Impacts potentiels positifs 3.2. Impacts potentiels négatifs 3.3. Impacts cumulatifs et résiduels 4. RESPONSABLITES ORGANISATIONNELLES 4.1. Cadre organisationnel nationale 4.2. Responsabilités de la mise en œuvre du présent PATI-PAP 5. PARTICIPATION ET CONSULTATIONS PUBLIQUES 5.1. Participation communautaire/Consultations publiques déjà réalisées 5.2. Consultation des PAPs 5.3. Enquêtes administratives 6. INTEGRATION DES COMMUNAUTES D’ACCUEIL 7. ETUDES SOCIO –ECONOMIQUES : Recensement des personnes affectées par le projet 7.1. -

Leishmaniasis in Northern Morocco: Predominance of Leishmania Infantum Compared to Leishmania Tropica

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2019, Article ID 5327287, 14 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5327287 Research Article Leishmaniasis in Northern Morocco: Predominance of Leishmania infantum Compared to Leishmania tropica Maryam Hakkour ,1,2,3 Mohamed Mahmoud El Alem ,1,2 Asmae Hmamouch,2,4 Abdelkebir Rhalem,3 Bouchra Delouane,2 Khalid Habbari,5 Hajiba Fellah ,1,2 Abderrahim Sadak ,1 and Faiza Sebti 2 1 Laboratory of Zoology and General Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Rabat, Morocco 2National Reference Laboratory of Leishmaniasis, National Institute of Hygiene, Rabat, Morocco 3Agronomy and Veterinary Institute Hassan II, Rabat, Morocco 4Laboratory of Microbial Biotechnology, Sciences and Techniques Faculty, Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, Morocco 5Faculty of Sciences and Technics, University Sultan Moulay Slimane, Beni Mellal, Morocco Correspondence should be addressed to Maryam Hakkour; [email protected] Received 24 April 2019; Revised 17 June 2019; Accepted 1 July 2019; Published 8 August 2019 Academic Editor: Elena Pariani Copyright © 2019 Maryam Hakkour et al. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In Morocco, Leishmania infantum species is the main causative agents of visceral leishmaniasis (VL). However, cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) due to L. infantum has been reported sporadically. Moreover, the recent geographical expansion of L. infantum in the Mediterranean subregion leads us to suggest whether the nonsporadic cases of CL due to this species are present. In this context, this review is written to establish a retrospective study of cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis in northern Morocco between 1997 and 2018 and also to conduct a molecular study to identify the circulating species responsible for the recent cases of leishmaniases in this region. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR13248 Implementation Status & Results Morocco MA-Regional Potable Water Supply Systems Project (P100397) Operation Name: MA-Regional Potable Water Supply Systems Project Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 6 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 01-Jan-2014 (P100397) Public Disclosure Authorized Country: Morocco Approval FY: 2010 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 15-Jun-2010 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2015 Planned Mid Term Review Date 14-Apr-2014 Last Archived ISR Date 20-Jun-2013 Effectiveness Date 15-Feb-2011 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2015 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The project development objective (PDO) is to increase access to potable water supply for selected communities in the project provinces of Nador, Driouch, Safi, Youssoufia, Sidi Bennour, and Errachidia. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Public Disclosure Authorized Yes No Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Component 1. Water production, conveyance and rural water supply in the Nador, Driouch, Safi, 165.40 Youssoufia, Sidi Bennour and Errachid ia provinces Sub-Component 1.a, for water production, conveyance and rural water supply in the Nador and 59.80 Driouch provinces Sub-component 1.b, for water production, conveyance and RWS in the Safi, Youssoufia and Sidi 83.40 Bennour provinces Sub-component 1.c, for rehabilitation and expansion of water production and conveyance capacity for 22.20 water supply in the Errachidia p rovince Public Disclosure Authorized Component 2. -

Etat Global PRDTS CONSEIL REGIONAL 2016

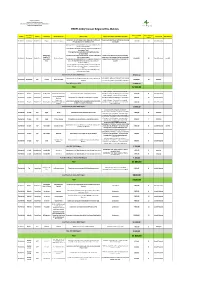

Région Fès-Meknès Direction Générale des Services Division d'Equipement Rural ETAT D'AVANCEMENT DES PROJETS PRDTS/CONSEIL REGIONAL FES-MEKNES/2016 ETAT GLOBAL Contribution Crédits Taux Préfécture / Crédits Commune Intitulé du projet secteur maitre d'ouvrage de la Région engagés Statut avancement avancement Observations Province émis (en KDH) (Kdh) (kDH) physique (en %) Fritissa, Tissaf Ermila, El Orjane, Ouled Ali versement effectué:12\05\2017 Boulemane Youssef,Missour, Mise à niveau de classes scolaires EDUCATION AREF 10 600,00 10 600,00 10 600,00 Achevé 100% Travaux achevés Outat El Haj, Enjil,Sidi Boutayeb, El Mers et Ait Baza DRETL/FES- versement effectué:30\12\2017 Boulemane Enjil Réhabilitation de la RR 503(PK 125 au PK 147) ROUTES/PISTES 21 600,00 21 600,00 21 600,00 Achevé 100% MEKNES Travaux achevés Aménagement de la RP 7039 reliant la RR 402 et DRETL/FES- ElHajeb ait bourzouine ROUTES/PISTES 2 000,00 la RP 7070 sur une longueur de 3 Km MEKNES Aménagement de la RP 7007 reliant la RR701 et DRETL/FES- ElHajeb jahjouh le centre de Jahjouh sur une longueur de 11,5 ROUTES/PISTES 4 000,00 6 200,00 4 648,36 Achevé 100% Travaux achevé MEKNES Km Construction de la RP 7057 reliant la ville d'El DRETL/FES- ElHajeb Iqaddar ROUTES/PISTES 1 800,00 Hajeb et la RR 712 sur une longueur de 4,5 Km MEKNES Travaux d'aménagement de la piste DayetSder reliant la RP 716 et douar Ait LahcenOumoussa, Conseil/Région travaux receptionés en date du ElHajeb Bitit ROUTES/PISTES 714,892 588,66 Achevé 100% DayetSder, Maamel Doum, et Ecole DayetSder Fès Meknès -

Pauvrete, Developpement Humain

ROYAUME DU MAROC HAUT COMMISSARIAT AU PLAN PAUVRETE, DEVELOPPEMENT HUMAIN ET DEVELOPPEMENT SOCIAL AU MAROC Données cartographiques et statistiques Septembre 2004 Remerciements La présente cartographie de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social est le résultat d’un travail d’équipe. Elle a été élaborée par un groupe de spécialistes du Haut Commissariat au Plan (Observatoire des conditions de vie de la population), formé de Mme Ikira D . (Statisticienne) et MM. Douidich M. (Statisticien-économiste), Ezzrari J. (Economiste), Nekrache H. (Statisticien- démographe) et Soudi K. (Statisticien-démographe). Qu’ils en soient vivement remerciés. Mes remerciements vont aussi à MM. Benkasmi M. et Teto A. d’avoir participé aux travaux préparatoires de cette étude, et à Mr Peter Lanjouw, fondateur de la cartographie de la pauvreté, d’avoir été en contact permanent avec l’ensemble de ces spécialistes. SOMMAIRE Ahmed LAHLIMI ALAMI Haut Commissaire au Plan 2 SOMMAIRE Page Partie I : PRESENTATION GENERALE I. Approche de la pauvreté, de la vulnérabilité et de l’inégalité 1.1. Concepts et mesures 1.2. Indicateurs de la pauvreté et de la vulnérabilité au Maroc II. Objectifs et consistance des indices communaux de développement humain et de développement social 2.1. Objectifs 2.2. Consistance et mesure de l’indice communal de développement humain 2.3. Consistance et mesure de l’indice communal de développement social III. Cartographie de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social IV. Niveaux et évolution de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social 4.1. Niveaux et évolution de la pauvreté 4.2. -

Assessing Vegetation Structural Changes in Oasis Agro-Ecosystems Using Sentinel-2 Image Time Series: Case Study for Drâa-Tafilalet Region Morocco

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-4/W12, 2019 5th International Conference on Geoinformation Science – GeoAdvances 2018, 10–11 October 2018, Casablanca, Morocco ASSESSING VEGETATION STRUCTURAL CHANGES IN OASIS AGRO-ECOSYSTEMS USING SENTINEL-2 IMAGE TIME SERIES: CASE STUDY FOR DRÂA-TAFILALET REGION MOROCCO L. Eddahby1*, M.A. Popov2, S.A. Stankevich2, A.A. Kozlova2, M.O. Svideniuk2, D. Mezzane3, I. Lukyanchuk4, A. Larabi1 and H. Ibouh5 1Laboratory LIMEN “Water Resources & Information Technology”, Mohammadia School of Engineers, BO 765 Agdal, Rabat, Morocco (*DEVS/DSP in the ANDZOA, Rabat, Morocco) [email protected]; 2Scientific Centre for Aerospace Research of the Earth, Kiev, Ukraine - [email protected]; 3LMCN, Faculty of Sciences and Techniques, Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakesh, Morocco; 4 LPMC, Picardie Jules Verne University, Amiens, France ; 5 LGSE, Faculty of Sciences and Techniques,Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakesh, Morocco - [email protected] Commission VI, WG VI/4 KEY WORDS: LAI,Oasis, Vegetation Structure, Time Series Analysis, Change Detection, Remote Sensing, Sentinel-2, Tafilalet, Morocco ABSTRACT: Nowadays, Moroccan oasis agro-ecosystems are under intense effect of natural and anthropogenic factors. Therefore, this essay proposes to use Leaf Area Index (LAI) to assess the consequences of the oases long-term biodegradation. The index was used as a widely-applied parameter of vegetation structure and an important indicator of plant growth and health. Therefore, a new optical multispectral Sentinel-2 data were used to build a long term LAI time series for the area of the Erfoud and Rissani oases, Errachidia province in Drâa-Tafilalet region in Morocco. -

PRDTS 2020/ Conseil Régional Fès-Meknès

Région Fès-Meknès Direction Générale des Services Direction d'Aménagement du Territoire et d'Equipement Division d'Equipement Rural PRDTS 2020/ Conseil Régional Fès-Meknès Préfecture/ Montant Global Durée du projet Région Secteur Communes Douars Desservis Intitulé Projet Nature Intervention (Consistance physique) M.O/M.O.D Observations Province kdh en mois Construction et renforcement de la route reliant la RN4 et la Travaux de construction et renforcement du corps Fès Meknès Boulemane Route/Piste Guigou Differents Douars 7 000,00 10 Conseil Régional RP 7235 via Douar Imi Ouallal sur 7 km de chaussée Amenagement et construction des pistes aux communes de la province de Boulemane: *Aménagement de la piste Timrast et Lbiyout Ouled Sidi Zian à la commune Tissaf *Amenagement de la piste Ziryoulat Oulad Boukays à la commune Tissaf Tissaf,guigou, *Construction de la piste reliant Laauine, Ait Besri et la RR7235 Travaux de construction du corps de chaussée, Serghina, El à la commune Guigou construction des ouvrages d'art et de traversées Fès Meknès Boulemane Route/Piste Plusieurs Douars 31 000,00 18 Conseil Régional voir NB Mers, Skoura *Construction de la piste reliant Ait Ali, Taghazout à travers Ait busées, travaux de protection et revetement y Mdaz Charo, Ait Abdlah et Ait Hsaine Ouhado aux communes bicouche Serghina et ElMars *Construction des pistes Tadout-Anakouine, Tadout-Chelal; Tadout-Ain Lkbir, Tikhzanine-Amalo à la commune Skoura Mdaz *Construction de la piste reliant Taghazout Sidi Mhyou à la commune Skoura Mdaz Total Routes et -

Morocco and United States Combined Government Procurement Annexes

Draft Subject to Legal Review for Accuracy, Clarity, and Consistency March 31, 2004 MOROCCO AND UNITED STATES COMBINED GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ANNEXES ANNEX 9-A-1 CENTRAL LEVEL GOVERNMENT ENTITIES This Chapter applies to procurement by the Central Level Government Entities listed in this Annex where the value of procurement is estimated, in accordance with Article 1:4 - Valuation, to equal or exceed the following relevant threshold. Unless otherwise specified within this Annex, all agencies subordinate to those listed are covered by this Chapter. Thresholds: (To be adjusted according to the formula in Annex 9-E) For procurement of goods and services: $175,000 [Dirham SDR conversion] For procurement of construction services: $ 6,725,000 [Dirham SDR conversion] Schedule of Morocco 1. PRIME MINISTER (1) 2. NATIONAL DEFENSE ADMINISTRATION (2) 3. GENERAL SECRETARIAT OF THE GOVERNMENT 4. MINISTRY OF JUSTICE 5. MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND COOPERATION 6. MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR (3) 7. MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATION 8. MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION, EXECUTIVE TRAINING AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH 9. MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION AND YOUTH 10. MINISTRYOF HEALTH 11. MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PRIVATIZATION 12. MINISTRY OF TOURISM 13. MINISTRY OF MARITIME FISHERIES 14. MINISTRY OF INFRASTRUCTURE AND TRANSPORTATION 15. MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (4) 16. MINISTRY OF SPORT 17. MINISTRY REPORTING TO THE PRIME MINISTER AND CHARGED WITH ECONOMIC AND GENERAL AFFAIRS AND WITH RAISING THE STATUS 1 Draft Subject to Legal Review for Accuracy, Clarity, and Consistency March 31, 2004 OF THE ECONOMY 18. MINISTRY OF HANDICRAFTS AND SOCIAL ECONOMY 19. MINISTRY OF ENERGY AND MINING (5) 20. -

280-JMES-4281-Amakrane.Pdf

Journal(of(Materials(and(( J. Mater. Environ. Sci., 2018, Volume 9, Issue 9, Page 2549-2557 Environmental(Sciences( ISSN(:(2028;2508( CODEN(:(JMESCN( http://www.jmaterenvironsci.com ! Copyright(©(2018,((((((((((((((((((((((((((((( University(of(Mohammed(Premier(((((( (Oujda(Morocco( Mineralogical and physicochemical characterization of the Jbel Rhassoul clay deposit (Moulouya Plain, Morocco) J. Amakrane1,2*, K. El Hammouti1, A. Azdimousa1, M. El Halim2,3, M. El Ouahabi2, B. Lamouri4, N. Fagel2 1Laboratoire des géosciences appliquées (LGA), Département de Géologie, Faculté des Sciences, Université Mohammed Premier, BP 717 Oujda, Morocco 2UR Argile, Géochimie et Environnement sédimentaires (AGEs), Département de Géologie, Quartier Agora, Bâtiment B18, Allée du six Août, 14, Sart-Tilman, Université de Liège, B-4000, Belgium 3Laboratoire de Géosciences et Environnement (LGSE), Département de Géologie, Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université Cadi Ayyad, BP 549 Marrakech, Morocco 4Laboratoire Géodynamique et Ressources Naturelles(LGRN), Département de Géologie, Faculté des Sciences de la Terre, Université Badji Mokhtar-Annaba, Algeria. Received 26 Jan 2018, Abstract Revised 08 Jun 2018, This study aims at the mineralogical and physicochemical characterization of clays of Accepted 10 Jun 2018 the Missour region (Boulemane Province, Morocco). For this, three samples were collected in the Ghassoul deposit. The analyses were carried by X-ray diffraction Keywords (XRD), X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). The thermal analysis from 500 to1100°C was also performed on studied samples, and the !!Clay, fired samples were characterized by XRD and SEM. The XRD results revealed that raw !!Ghassoul, Ghassoul clay consists mainly of Mg-rich trioctahedral smectite, stevensite-type clay, !!Characterization, which represents from 89% to 95% of the clay fraction, with a small amount of illite !!Stevensite, and kaolinite.