Pirates Punks & Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finnland Hamburg · 14.10.2009

aktuell OFFIZIELLES PROGRAMM DES DEUTSCHEN FUSSBALL-BUNDES · 6/2009 · SCHUTZGEBÜHR 1,– ¤ WM-Qualifikationsspiel Deutschland – Finnland Hamburg · 14.10.2009 Mit Super-Gewinnspiel und Riesen-Poster! www.dfb.de · www.fussball.de 200 Hektar Anbaufläche Jahre Erfahrung Dr. Georg Stettner 20 Qualitätsprüfer 1 Blick fürs Detail Unser Anspruch ist es nur die beste Braugerste zu verarbeiten. Daher verwenden wir nur ausgewählte Gerstensorten. Diese Sorgfalt für unser Gerstenmalz schmecken Sie mit jedem Schluck. Alles für diesen Moment: Liebe Zuschauer, unsere Nationalmannschaft hat sich in Moskau wieder ein- mal von ihrer besten Seite gezeigt und die Lobeshymnen auf ihre starke Leistung, die überall zu lesen und zu hören sind, sind vollauf berechtigt. Bereits kurz nach dem Spiel beim gemeinsamen Essen im Hotel habe ich mich bei ihr und den Trainern für einen unvergesslichen Fußball-Abend bedankt. Unser Team hat sich bei dem Sieg gegen Russland so präsentiert, wie sich das Millionen Fans wünschen. Die DFB-Auswahl hat gleichzeitig eindrucksvoll bewiesen, dass sie das Flaggschiff des deutschen Fußballs ist. Damit hat sie sich vor der letzten, heute auf dem Terminplan stehenden WM-Qualifikations-Begegnung mit Finnland direkt für das Stelldichein der 32 weltbesten National mann - schaften im kommenden Sommer in Südafrika qualifiziert. Zum 15. Mal in Folge seit 1954 ist damit unser Team bei der WM-Endrunde dabei. Natürlich erfüllt uns das alle mit Stolz, zumal die DFB-Auswahl zum wiederholten Mal in Moskau bewiesen hat, dass in wichtigen Duellen einfach Verlass auf sie ist, sie sich im entscheidenden Moment nicht nur kämpferisch, sondern genauso spielerisch immer steigern kann und zu Recht in der FIFA-Weltrangliste zu den Topteams gehört. -

05-08-12Hessenloewe.Pdf

Oddset Oberliga Hessen KSV Hessen Kassel Ausgabe 01 | August 2005 www.ksv-hessen.de HESSEN LÖWE DAS KASSELER FUSSBALLMAGAZIN Matthias Hamann Oddset Oberliga Hessen Es ist nicht wichtig, wer als Erster Im August kommen die Aufsteiger. losläuft, sondern wer als Erster ankommt. Wetten. Fiebern. Gewinnen. Hessenlöwe Anpfi ff Willkommen INHALT AUGUST GewinneGewinne Endlich wieder Fußball im Neues 04 Kasseler Auestadion. Impressum 04 Wechselbörse 07 Foto: T. Siebrecht T. Foto: Die diesjährige Sommerpause Lübeck)verstärkt. Fehlt nur imim Anflug!Anflug! hat uns viele Fußball beschert. noch ein Stürmer werden viele Confederation Cup, Europa- sagen. Richtig, wir haben und meisterschaft der Damen und, werden weiter unsere Fühler Jetzt mit ODDSET in der Bundesliga abstauben. und, und. Doch trotzdem, dass nach einer echten Verstärkung es viel Fußball zu sehen gab, im Angriff ausstrecken. Bis zum freue ich mich endlich wieder Ende des Monats ist das Trans- Interview mit die Löwen hautnah und live ferfenster noch geöffnet und Matthias Hamann 08 im Auestadion zu erleben. Ich seit dieser Spielzeit bietet sich begrüße Sie recht herzlich zu erstmals für Amateurvereine Premium-Partner den Heimspielen in der Saison die Möglichkeit einen Spieler ei- des KSV 11 2005/2006 beim KSV Hessen ner Lizenzmannschaft auszulei- Kassel. hen. Eins ist aber sicher, wir werden nur dann einen weiteren Stür- TSG Wattenbach 13 mer verpfl ichten wenn a.) es sich um eine echte Verstärkung und In der sogenannten „Sommer- nicht um eine Ergänzung handelt und b.) der fi nanzielle Rahmen FC Bayern Alzenau 15 pause” ist rund um den Club nicht gesprengt wird! Drücken wir uns gemeinsam die Daumen! einiges passiert. -

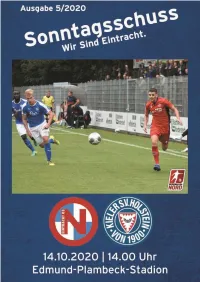

Heimspiel Gegen Holstein Kiel (U23)

Liebe Fußball-Fans, nach dem nicht optimalen Saisonstart mit zwei Niederlagen in Flensburg sowie zuhause gegen Drochtersen/Assel hat unsere Mannschaft die richtige Antwort gegeben und zwei wichtige Siege eingefahren, die unterschiedlicher nicht sein konnten. Bei Aufsteiger 1.FC Phönix Lübeck gab es einen deutlichen und souveränen 3:0- Auswärtserfolg, bei dem sich unser Torhüter Lars Huxsohl unter anderem durch einen gehaltenen Foulelfmeter auszeichnen konnte. Vier Tage später war die U21 des Hamburger SV zu Gast im Edmund-Plambeck-Stadion. Früh im Spiel verloren wir Innenverteidiger Fabian Grau nach einer Kollision mit dem Torpfosten durch eine schwere Hüftprellung, zudem ging der HSV im ersten Durchgang zwei Mal in Führung. Mit einer sehr einsatzfreudigen Leistung und viel Willen konnte man das Spiel in der zweiten Hälfte noch drehen. Nach einem Platzverweis gegen Youngster Batuhan Evren mussten wir die letzten Minuten in Unterzahl spielen, was unserer Mannschaft – angetrieben von den Zuschauern, die jeden Ballgewinn lautstark bejubelten – bestens gelang. Heute ist die U23 von Holstein Kiel zu Gast in Norderstedt, die sich zu einem großen Teil aus Spielern des eigenen Nachwuchsleitungszentrums zusammen setzt. Mit Stürmer Laurynas Kulikas und unserem ehemaligen Jugendspieler Eric Gueye haben die Jungstörche zwei Spieler im Kader, die unsere Anlage bestens kennen. Das Team von Neu-Trainer Sebastian Gunkel musste nach einem Auftaktsieg zuletzt drei Niederlagen in Folge einstecken und steht im Tabellenkeller. Doch bei der zweifellos großen Qualität im Kader ist es nur eine Frage der Zeit, bis sich die jungen Kieler Neuzugängen an die Regionalliga gewöhnt haben und sich die Erfolge einstellen. Bei uns herrscht nach wie vor Personalmangel. -

Turnierheft Kurt-Hornung-Hallenmasters 2020

Kurt-Hornung-Masters 2020 Grusswort des Jugendleiters Sehr geehrte Besucher der sechsten Auflage des Kurt-Hornung-Hallenmasters. Dieses im Jahre 2014 ins Leben gerufene Hallenfußballturnier für U14-Mannschaen geht auf die Iniave von Sporreund Dominik Hildebrand zurück, der beim FV Malsch seine ersten Schrie im Fußballsport als Spieler und junger Trainer wagte und über die Staon Kuppenheim schließlich beim Offenburger FV landete, wo er milerweile als Kooperaonstrainer zum SC Freiburg ganz dicht am großen Fußball ist. Namensgeber des Turniers ist Kurt Hornung, der Großvater von Dominik Hildebrand. Kurt Hornung hat sich in seiner langjährigen sportlichen und ehrenamtlichen Tägkeit im FV Malsch viele Verdienste erworben. Er war ein Mensch mit klarem Charakter, der zuhören konnte – ein Mann, dem man vertrauen konnte. Er ging humorvoll durchs Leben und hae dabei immer einen klaren Blick auf das Erreichbare im Leben und auf das Erreichbare für seinen FV Malsch. Für seinen großen Einsatz für das Malscher Vereinsleben wurde Kurt Hornung vielfach ausgezeichnet, so zum Beispiel vom Badischen Sportbund und vom Land Baden-Würemberg. Der FV Malsch kann sich glücklich schätzen, dass er lange Jahre am Einsatz seines Ehrenmitglieds Kurt Hornung wachsen konnte. Aber auch, dass er über sein direktes Wirken hinaus durch dieses Turnier wachsen und profitieren kann. Die Jugendabteilung nimmt die Aufgaben, die mit diesem Erinnerungsturnier verbunden sind, mit Freude aber auch mit großer Dankbarkeit gegenüber den vielen Helfern und Gönnern an, ohne die eine solche Aufgabe nicht zu bewältigen ist. Kurt-Hornung-Masters 2020 Neben Dominik Hildebrand und den vielen Ehrenamtlichen aus dem Verein sind dies insbesondere die zahlreichen Eltern unserer Nachwuchsfußballer aber nicht zuletzt auch die zahlreichen Unterstützer, allen voran unser Turniersponsor Heinz von Heyden Massivhäuser. -

Fussball Magazin Für Den Nachwuchs

FUSSBALL MAGAZIN FÜR DEN NACHWUCHS CD MIT EXKLUSIVEN cSONGS! SAISON 2007/08 | 2,30 EURO [SCHUTZGEBÜHR] EDITORIAL 2 3 Vor einem knappen Jahr erschien die erste Ausgabe der zu betreiben. Dass der Autor der Titelgeschichte bei seinen Recherchen mit dem Verdacht „Young Rebels“. Geschichten über den Nachwuchsbereich der Industriespionage konfrontiert wurde, offenbart den vermeintlichen Stellenwert, den des F C St. Pauli – ein zum damaligen Zeitpunkt chronisch so mancher Verein inzwischen seiner Nachwuchsarbeit beimisst. liquiditätsgefährdeter Regionalligist, der trotz der dringend angepeilten Rückkehr in den Profifußball seine Zurück im Profifußball ist die Konkurrenz jedenfalls größer geworden! Können zwei Vereine Nachwuchsarbeit nicht endgültig aufgegeben hatte. Was in ein und derselben Stadt nebeneinander existieren oder in puncto Nachwuchsarbeit vor wenigen Monaten manchem noch als Luxus erschienen sogar voneinander profitieren? Ein Vergleich mit dem anderen großen sein mag, ist spätestens durch den Wiederaufstieg in die Hamburger Club zeigt Wege und Grenzen. Kann die Ausbildung jugendlicher Talente für einen Verein mehr 2. Bundesliga zu einem Bestandteil der Lizenz- Auflagen bedeuten als ein PR-wirksames Lippenbekenntnis? Oder ist sie in Wahrheit gar die Basis geworden. für nachhaltigen sportlichen und wirtschaftlichen Erfolg? Fast schon eine philosophische Frage. Letztlich muss der F C St. Pauli seinen eigenen Weg gehen. Inwieweit die Weichen Im deutschen Profifußball gelten für alle die selben hierfür gestellt sind, wollen wir in diesem Magazin untersuchen. Rahmenbedingungen. Und dennoch verfolgen die Vereine ganz unterschiedliche Ansätze, wenn es darum geht, Die Redaktion Nachwuchsarbeit als Unterbau für den professionellen Erfolg www.hochbahn.de Teamgeist auf ganzer Linie. Der FC St. Pauli und die HOCHBAHN: zwei Teams mit Tradition, die seit fast 100 Jahren motiviert und engagiert in Hamburg spielen. -

Offenburger FV Samstag 09

Herzlich Willkommen im Erletal-Stadion Willkommen im Erletal-StadionVerbandsliga Saison 2017/2018 SV Endingen – Offenburger FV Samstag 09. Dezember – 14.30 Uhr Sehr verehrte Fußballfreunde im Namen des gesamten SV Endingen dürfen wir Sie zum heutigen Heimspiel am 19. Spieltag gegen den Offenburger FV im Endinger „Erletal-Stadion“ begrüßen. Ein ganz besonderer Gruß geht natürlich an unseren heutigen Gast aus Offenburg, mit ihrem Trainer Kai Eble und Co-Trainer Frank Armburster sowie den gesamten Betreuerstab und alle mitgereisten Fans der Ortenau. Recht herzliche Grüße auch an das Schiedsrichtergespann vom Bezirk Bodensee. Das heutige Spiel steht unter der Leitung von Referee Dario Litterst. Seine beiden Assistenten an der Linie sind Maximilian Würzer und Johannes Mock. Sie alle heißen wir hier recht herzlich willkommen und wünschen allen Zuschauern ein faires und spannendes Verbandsliga-Spiel zwischen unserem Gast dem Offenburger FV (5. Platz) und unserem SV Endingen (8. Platz). Die Winterpause im Erle steht kurz bevor und wir möchten Ihnen und Ihren Familien im Namen des gesamten SV Endingen eine schöne Adventszeit und frohes Weihnachtsfest wünschen. Wir bedanken uns zudem bei allen Trainern, Spielern, Helfern für die Stunden im Erle für den SVE. Halloween Party 31.10.2017 war wieder ein voller Erfolg Wir danken allen Helfern für die Unterstützung ohne die die Umsetzung eines solchen Events nicht möglich gewesen wäre. Bubble Soccer Turnier 05.01.2018 Zum Abschluss unseres diesjährigen Hallenturniers veranstalten wir zum ersten Mal ein Bubble Soccer Turnier für Vereine, www.svendingen.deBetriebe und Freizeitmannschaften. Mehr Infos unter www.svendingen.de Anmeldungen an [email protected] www.svendingen.de www.svendingen.de Der Trainer hat das Wort Willkommen im Erletal-Stadion Spiel. -

No Football for Fascists

No Football for Fascists: How FC St. Pauli gathered a worldwide left-wing fanbase Name: Paul Bakkum Student number: 11877472 Thesis supervisor: dr. M. J. Föllmer University of Amsterdam, 01-07-2020 Contents; Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Preface ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 The Context of the St. Pauli district and FC St. Pauli ................................................................ 9 Harsh living conditions and political unrest in St. Pauli ........................................................ 9 A short history of FC St. Pauli ............................................................................................. 12 A Supporters Revolution .......................................................................................................... 15 The Early ‘80s ...................................................................................................................... 15 A growing movement ........................................................................................................... 21 An organised movement ....................................................................................................... 23 The introduction -

Sieben Begegnungen Nur Mittelmaß Und Musste Zunächst Mit 6:8

29 sieben Begegnungen nur Mittelmaß und Das abschließende Auswärtsspiel beim VfR musste zunächst mit 6:8-Punkten um einen Heilbronn ging jedoch mit 0:3 verloren. Mit gesicherten Mittelplatz kämpfen. Es war der Erreichung des sechsten Tabellenplatzes unbegreiflich, dass mit diesen profilierten in der Oberliga Baden-Württemberg hatte sich Spielern keine durchschlagende Truppe auf der Offenburger FV aber wieder gut die Beine gestellt werden konnte. Und schon geschlagen. läuteten die Alarmglocken! Zu dieser Quasi als Jubiläumsgeschenk im 75. Enttäuschung kam die Tatsache, dass die Bestehungsjahr errang der OFV seine dritte Neuzugänge Dobiasch, Fesel und Traut nicht Südbadischer Pokalmeisterschaft. Nach einschlugen und die Leistungen der Siegen über SV Weil (4:2 n.V.), FV Mannschaft immer schlechter wurden. Schutterwald (4:1), SV Bühlertal (4:2), FC 08 Am 06. März 1981 beschloss der Vorstand, Villingen (2:1), Sportfreunde DJK Freiburg Trainer Becker wegen Vertragsbruch zu (1:0) war das Finale erreicht. Das Endspiel beurlauben. Dem Verein war zu Ohren fand am 27. Mai 1982 in Reute gegen den gekommen, dass Becker für eine Verbandsligisten SV Kirchzarten statt. Der Spielervermittlung zum OFV angeblich Geld 3:1-Sieg war eine Art Entschädigung für kassiert hatte. Seine Stelle nahm der Trainer manche unglücklichen Begegnungen in der der II. Mannschaft Paul Leinz ein. Mit 17:7 Punkterunde. Und vor allem: der OFV kann Punkten in Folge schaffte Interimstrainer doch ein Entscheidungsspiel oder Finale Leinz mit dem vor der Runde als Top-Favorit gewinnen! gehandelte OFV am Saisonschluss noch den sechsten Tabellenplatz. Das Südbadische Pokalfinalspiel gegen den FC Rastatt 04 ging im Juni 1981 in Achern leider mit 0:3 verloren. -

The Law on All‑Seated Stadiums in England and Wales and the Case for Change

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-space: Manchester Metropolitan University's Research Repository Rigg, David (2018)Time to take a stand? The law on all-seated stadiums in England and Wales and the case for change. The International Sports Law Journal, 18 (3-4). pp. 210-218. ISSN 1567-7559 Downloaded from: http://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/621742/ Version: Published Version Publisher: Springer DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40318-018-0136-9 Usage rights: Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Time to take a stand? The law on all-seated stadiums in England and Wales and the case for change David Rigg The International Sports Law Journal ISSN 1567-7559 Int Sports Law J DOI 10.1007/s40318-018-0136-9 1 23 Your article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution license which allows users to read, copy, distribute and make derivative works, as long as the author of the original work is cited. You may self- archive this article on your own website, an institutional repository or funder’s repository and make it publicly available immediately. 1 23 The International Sports Law Journal https://doi.org/10.1007/s40318-018-0136-9 ARTICLE Time to take a stand? The law on all‑seated stadiums in England and Wales and the case for change David Rigg1 © The Author(s) 2018 Abstract In June 2018, the UK Government announced a review of the ban on standing at football matches in the Premier League and Championship. -

Is There a Neeskens-Effect?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Leininger, Wolfgang; Ockenfels, Axel Working Paper The penalty-duel and institutional design: is there a Neeskens-effect? CESifo Working Paper, No. 2187 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Leininger, Wolfgang; Ockenfels, Axel (2008) : The penalty-duel and institutional design: is there a Neeskens-effect?, CESifo Working Paper, No. 2187, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/26232 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu THE PENALTY-DUEL AND INSTITUTIONAL DESIGN: IS THERE A NEESKENS-EFFECT? WOLFGANG LEININGER AXEL OCKENFELS CESIFO WORKING PAPER NO. -

Erhebung Und Konzeptualisierung Der Kernkompetenzen Von

! Erhebung und Konzeptualisierung der Kernkompetenzen von erfolgreichen Fussballtrainern - Eine Untersuchung anhand der deutschen Bundesliga und der Schweizer Super League D I S S E R T A T I O N der Universität St. Gallen, Hochschule für Wirtschafts-, Rechts- und Sozialwissenschaften, Internationale Beziehungen und Informatik (HSG), zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Wirtschaftswissenschaften vorgelegt von Christian Lang von Weiningen (Zürich) Genehmigt auf Antrag der Herren Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Jenewein und Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Torsten Tomczak Dissertation Nr. 5057 Difo-Druck GmbH, Untersiemau 2021 ! ""! Die Universität St.Gallen, Hochschule für Wirtschafts-, Rechts- und Sozialwissenschaf- ten, Internationale Beziehungen und Informatik (HSG), gestattet hiermit die Drucklegung der vorliegenden Dissertation, ohne damit zu den darin ausgesprochenen Anschauun- gen Stellung zu nehmen. St. Gallen, 23. Oktober 2020 Der Rektor: Prof. Dr. Bernhard Ehrenzeller ! """! !"#$%"&'#&( ! Das Verfassen der vorliegenden Doktorarbeit verlangte ein hohes Mass an Durchhalte- vermögen und Selbstdisziplin. Rückblickend empfinde ich, dass die illustrative Kurve im nachfolgenden Flow-Modell1 – einem der favorisierten Konzepte meines geschätzten Doktorvaters – meine Stimmungslage und Entwicklung als Doktorand gut zu beschreiben vermag. Insbesondere eignet sich dieses Modell, da Kompetenzen in Verbindung mit den Anforderungen das Kernthema der nachfolgenden Dissertation bilden. ! !!!!!!!! ! ! Ich hatte das Glück, während meiner Promotion den sogenannten ‚Flow‘-Zustand -

Oberliga Baden-Württemberg - Regionalliga Südwest

Oberliga Baden-Württemberg - Regionalliga Südwest Mi, 24.05.17 SV Röchl. Völklingen : FSV 08 Bissingen 1:0 19.00 Uhr Sa, 27.05.17 FSV 08 Bissingen : SG Rotweiß Frankfurt 4:0 14.00 Uhr Mi, 31.05.17 SG Rotweiß Frankfurt : SV Röchl. Völklingen 1:1 19.00 Uhr Mit dem SC Freiburg 2 als Meister der Oberliga-Baden-Württemberg und des TSV Schott Mainz als Meister der Oberliga Rheinland-Pfalz/Saar sowie dem Zweitplatzierten der Hessenliga Eintracht Stadtallendorf (der Meister SG Hessen Dreieich hat auf den Aufstieg verzichtet) stehen bereits drei Aufsteiger in die Regionalliga Südwest fest. Die drei Vize-Meister SG Rot-Weiß Frankfurt (Hessenliga), SV Röchl. Völklingen (Oberliga Rheinland-Pfalz/Saar) und FSV 08 Bissingen (Oberliga-Baden- Württemberg) spielen in einer „3er-Runde“ im Modus „Jeder gegen Jeden“ den vierten Aufsteiger in die Regionalliga Südwest aus. Verbandsliga - Oberliga Baden-Württemberg Der Meister steigt direkt in die Amateuroberliga auf und der Vize-Meister bestreitet Aufstiegsspiele mit den Vize-Meistern von Südbaden und Württemberg um einen weiteren Aufsteiger. Zunächst spielen die beiden badischen Rangzweiten gegeneinander und der Sieger trifft dann auf den wfv- Vertreter. Vize Südbaden: Vize Baden: Mi, 31.05.17 : 4:0 Freiburger FC FV Fortuna Heddesheim Vize Baden: Vize Südbaden: Sa, 03.06.17 : 2:2 FV Fortuna Heddesheim Freiburger FC Vize Württemberg: Sieger Südbaden/Baden: Sa, 10.06.17 : 2:3 TSG Backnang Freiburger FC Sieger Südbaden/Baden: Vize Württemberg: So, 18.06.17 : Freiburger FC TSG Backnang Absteigen müssen von der Oberliga Baden-Württemberg in die Verbandsligen FSV Hollenbach (wfv), Offenburger FV (SBFV) und die SpVgg Neckarelz.