Allenatori Educatori Di Persone ENG.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholic Times

The TIMES CatholicThe Diocese of Columbus’ Information Source April 25, 2021 • FOURTH SUNDAY OF EASTER • Volume 70:15 Inside this issue Missionary discipleship: Marc Hawk of RevLocal in Granville takes a missionary discipleship approach as a Catholic businessman and entrepreneur, making service to clients, others and family the primary focus in all of his endeavors, Page 3 Autism Awareness: April is Autism Awareness Month and Catholic parents discuss raising children who are on the spectrum, their experiences in the Church and how diocesan parishes have worked with them, Page 8 School retreats: Bishop Watterson students Victoria Alves (left) and Gina Grden participate in an activity during a retreat, which are being held this year at diocesan high schools despite challenges presented by the pandemic, Page 10 OUR LADY OF PEACE CHURCH, SCHOOL STILL GOING STRONG AFTER 75 YEARS Pages 12-13 Catholic Times 2 April 25, 2021 Local news and events Columbus Catholic Renewal to sponsor praise meeting The Columbus Catholic Renewal ther Toner at patricktoner00@gmail. Father Smith to speak at retreat football, boys and girls lacrosse, boys organization will sponsor a citywide com or 473 S. Roys Ave., Columbus Father Stephen Smith, parochi- soccer, girls soccer, track and girls praise and adoration meeting from 10 OH 43204. al vicar at Powell St. Joan of Arc volleyball. Go to bishopwatterson. a.m. to noon Saturday, April 24 at Co- Church, will lead a men’s retreat at com/athletics/eagle-summer-sports- lumbus Our Lady of the Miraculous Josephinum 4-Miler to resume the Maria Stein Spiritual Center in camps for dates, registration and other Medal Church, 5225 Refugee Road. -

VOLUNTEER TRAINING of TRAINER's MANUAL (Tots)

5th - 16th February, Guwahati & Shillong VOLUNTEER TRAINING OF TRAINER’S MANUAL (ToTs) 1 2 Contents VOLUNTEER TRAINING OF TRAINER’S MANUAL (ToTs) 1 GUWAHATI & SHILLONG 1 VOLUNTEER FUNCTIONAL AREA 2 5TH TO 16TH OF FEBURARY , 2016 2 1. SOUTH ASIAN GAMES 5 History 5 Culture Value 5 Peace, Perseverance & Progress 5 Member Countries 5 Bi annual event 5 2. NORTH EAST INDIA 6 Culture & Tradition of north India 6 Legacy 7 Organising Committee 12th South Asian Games 2106 3. VISION AND MISSION 8 Vision 8 Mission 8 4. EVENTS AND VENUES 8 Guwahati 8 Shillong 9 Functional Areas 9 5. VOLUNTEERS 17 Concept of volunteering 17 Benefits of becoming a volunteer 17 The volunteer Honour code 18 DO’S 18 DONT’S 19 6. ACCREDITATION 19 What is accreditation? 19 People requiring accreditation 19 3 Importance of accreditation 19 The accreditation card 20 Venues and zones 20 Access Privileges 20 Non Transferability of the accreditation card 20 7. WORKFORCE POLICIES 20 Appropriate Roles for Volunteers and its Policy : 20 1.Volunteers being absent from work : 20 2.Entry & Check in Policy for Volunteers: 20 3.Exit Checkout Policy for Volunteers: 21 4.Sub specific policies 21 8. DISCIPLINE OF VOLUNTEERS 21 Volunteer Grievance Redressal 22 9. BEHAVIOUR OF VOLUNTEERS 22 Respect for Others 22 Ensure a Positive Experience 23 Act professionally and take responsibility for actions 23 10. LEADERSHIP 23 Roles of Volunteers 23 A volunteer leader is a volunteer who: 23 Orienting and Training Volunteers 23 11. ENERGY ENTHUSIASM 24 12. PROBLEM SOLVING 24 OVERCOMING OBSTACLES 24 13. COMMUNICATION 25 Listening 25 Listen Actively 25 SPEAKING 25 14. -

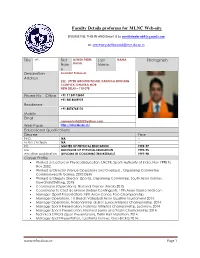

View Profile

Faculty Details proforma for MLNC Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] cc: [email protected] Title MR. First ASHISH PREM Last NAMA Photograph Nam SINGH Name e Designation Assistant Professor Address 222- UPPER GROUND FLOOR, KAKROLA HOUSING COMPLEX, DWARKA MOR NEW DELHI – 110 078 Phone No Office +91 11 24112604 +91 9818049974 Residence +91 8076768110 Mobile Email [email protected] Web-Page http://mlncdu.ac.in/ Educational Qualifications Degree Year Ph.D. NA -- M.Phil. / M.Tech. NA -- PG MASTER OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION 1995-97 UG BACHELOR OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION 1992-95 Any other qualification DIPLOMA IN COACHING [BASKETBALL] 1997-98 Career Profile Worked as Lecture in Physical Education, LNCPE, Sports Authority of India, Nov 1998 to Nov 2002. Worked as Director (Venue Operations and Overlays) , Organising Committee Commonwealth Games, 2010 Delhi Worked as Deputy Director (Sports), Organising Committee, South Asian Games, Guwahati/Shillong, 2015. Coordinator (Operations), National Games, Kerala 2015. Coordinator to Chef de Mission (Indian Contingent), 17th Asian Games Incheon. Manager (Sport Presentation) 15th Asian Canoe Polo Championship. Manager Operations, 1st Beach Volleyball Asian Qualifier tournament 2014. Manager Operations, National Inter-district Junior Athletics Championship, 2014. Manager Sports Presentation, National Athletics Championship, Lucknow, 2014. Manager Sports Presentation, National Junior and Youth Championship 2014. Technical Official (Sport Presentation), Delhi Half Marathon, 2014. Manager Sport Presentation, Lusofonia Games, Goa (India) 2014. www.mlncdu.ac.in Page 1 Administrative Assignments THE INTERNATIONAL SESSION FOR EDUCATORS AND OFFICIALS OF HIGHER INSTITUTES OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION, International Olympic Academy, Athens (GREECE) June 2011. Sports Administration of the Olympic Solidarity, Sports Administration Programme2004. -

To the Members of the John Paul II Foundation: the Formation of the Young Is an Investment for the Future

N. 161021a Friday 21.10.2016 To the members of the John Paul II Foundation: the formation of the young is an investment for the future This morning in the Consistory Hall Pope Francis received the members of the St. John Paul II Foundation, whose president is Cardinal Stanislaw Rylko, and which celebrates its 35th anniversary this year. The Foundation supports initiatives of an educational, cultural, religious and charitable character, inspired by St. John Paul II, whose liturgical memory is celebrated tomorrow, and is active in various countries especially in Eastern Europe, where it has enabled many students to complete their studies. The celebration of the anniversary allows the Foundation to evaluate the work that has been carried out so far, and at the same time to look to the future with new aims and objectives. The Pope therefore encouraged its members to continue their efforts in the promotion and support of younger generations, so that they may face life’s challenges, always inspired by an evangelical sensibility and the spirit of faith. “The formation of the young is an investment for the future: may the young never be robbed of their hope for a better tomorrow!”. “The Jubilee Year that is coming to an end encourages us to reflect and meditate on the greatness of God’s mercy in a time in which humanity, due to advances in various fields of technology and science, tends to consider itself to be self-sufficient, as if it were emancipated from any higher authority, believing that everything depends on itself alone. As Christians, however, we are aware that everything is a gift from God and that the true wealth is not money, which on the contrary can enslave, but rather God’s love, which sets us free”. -

Goa University Glimpses of the 22Nd Annual Convocation 24-11-2009

XXVTH ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 asaicT ioo%-io%o GOA UNIVERSITY GLIMPSES OF THE 22ND ANNUAL CONVOCATION 24-11-2009 Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon ble President of India, arrives at Hon'ble President of India, with Dr. S. S. Sidhu, Governor of Goa the Convocation venue. & Chancellor, Goa University, Shri D. V. Kamat, Chief Minister of Goa, and members of the Executive Council of Goa University. Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon'ble President of India, A section of the audience. addresses the Convocation. GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 XXV ANNUAL REPORT June 2009- May 2010 GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 206 GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 GOA UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR H. E. Dr. S. S. Sidhu VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. Dileep N. Deobagkar REGISTRAR Dr. M. M. Sangodkar GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 CONTENTS Pg, No. Pg. No. PREFACE 4 PART 3; ACHIEVEMENTS OF UNIVERSITY FACULTY INTRODUCTION 5 A: Seminars Organised 58 PART 1: UNIVERSITY AUTHORITIES AND BODIES B: Papers Presented 61 1.1 Members of Executive Council 6 C; ' Research Publications 72 D: Articles in Books 78 1.2 Members of University Court 6 E: Book Reviews 80 1.3 Members of Academic Council 8 F: Books/Monographs Published 80 1.4 Members of Planning Board 9 G. Sponsored Consultancy 81 1.5 Members of Finance Committee 9 Ph.D. Awardees 82 1.6 Deans of Faculties 10 List of the Rankers (PG) 84 1.7 Officers of the University 10 PART 4: GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 1.8 Other Bodies/Associations and their 11 Composition General Information 85 Computerisation of University Functions 85 Part 2: UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS/ Conduct of Examinations 85 CENTRES / PROGRAMMES Library 85 2.1 Faculty of Languages & Literature 13 Sports 87 2.2 Faculty of Social Sciences 24 Directorate of Students’ Welfare & 88 2.3 Faculty of Natural Sciences 31 Cultural Affairs 2.4 Faculty of Life Sciences & Environment 39 U.G.C. -

JULY 2019 ISSN 2094-6570 Vol

Inside DOST launches ‘nuLab” to discover future scientist, innovators ......................................... p3 Chris Tiu named as DOST ambassador .......... p4 InFocus ............................................................ p4 12 years of bringing S&T good news JULY 2019 ISSN 2094-6570 Vol. 12 No. 6 DOST-supported projects Technological innovations help achieve make physical therapy UN dev’t goals, science chief says easier in PH Text and photo by Marshall Louie M. Asis, DOST-STII By Angelica Marie Paz, DOST-STII n the Philippines, there are only 33,000 licensed physical therapists out of almost I105 million population. To address this shortage, experts from the De La Salle University Institute of Biomedical Engineering and Health Technologies (DLSU- IBEHT) developed two technologies that can assist physical therapists in doing rehabilitation treatments. These are the Agapay Project, catered to the upper extremities, and the Tayô Project for the lower extremities. The two projects are supported by the Department of Science and Technology- Philippine Council for Health Research and Development. Agapay Project Agapay is an artificial intelligence-assisted In a live interview with host Tony Velasquez (right) of ANC’s “Future Perfect”, DOST Secretary therapy innovation that aids the upper limbs Fortunato T. de la Peña (left) highlights the important role of the country’s technological innovations in (shoulder, elbow, wrist) of patients so they can achieving the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. regain their motor control. The SEMG or surface electromyography enables it to detect muscle contraction. he Philippine government marked the food security, energy, and environment; aging It is designed as a wearable robot that acts achievements of Filipino scientists society, health, and medical care; S&T human as an external skeleton that can assist the motor Tand science experts as the country resource development; equity and growth in movements of the patients. -

St. Bartholomew the Apostle Catholic Church

St. Bartholomew the Apostle Catholic Church 5356 Eleventh Street, Katy, TX 77493 281-391-4758 www.st-bart.org October 25, 2020 • 25 de Octubre del 2020 Welcome! ¡Bienvenidos! Father Father Father Deacon Deacon Deacon Deacon Christopher Plant Ricardo Arriola Santy Kurian William Wagner Fred Dinges Rolando Garcia Gordon Robertson Pൺඌඍඈඋ Pൺඋඈർඁංൺඅ Pൺඋඈർඁංൺඅ Pൺඌඍඈඋൺඅ Dංඋൾർඍඈඋ ඈൿ Dංඋൾർඍඈඋ ඈൿ Vංർൺඋ Vංർൺඋ Aඌඌංඌඍൺඇඍ Lංඍඎඋඒ Hංඌඉൺඇංർ Mංඇංඌඍඋංൾඌ Bൾ Fൺංඍඁൿඎඅ! Bൾ Hඈඅඒ! Bൾ ൺ Dංඌർංඉඅൾ ඈൿ Cඁඋංඌඍ! CONNECT WITH US MASS TIMES (All Public) RECEPTION HOURS Daily Masses / Misas Diarias A receptionist is available to take your Facebook: (all live-streamed) calls to the parish office on SaintBartholomewKaty or Monday - Friday FrPlant Monday - Friday Lunes a Viernes 9:00 AM to 3:00 PM. YouTube: 8:30 am English Limited deliveries, drop-offs, and Mass Saint Bartholomew or Tuesday & Thursday intentions may be accepted during this Conversing Clergy Martes y Jueves time. Email is the best way to reach the office staff. Visit the website for more Flocknote: 7:00 pm Español Saturday / Sábado information and updates. Stbartholomewkaty.flocknote.com 8:30 am First Saturday only, English [email protected] Sign up for Flocknote today and Weekend Masses receive weekly e-mails with updates Una recepcionista está disponible para on the sacraments, CCE and other (see website for streaming schedule) recibir sus llamadas a la oficina de la parish information. Saturday / Sábado parroquia 5:00 pm English Registrese hoy para Flocknotes y Lunes - Viernes 7:00 pm Español 9:00 AM a 3:00 PM. -

Not Just Games, There's Business Too

GOA Not just Games, there's business too Alexandre Moniz Barbosa, TNN Dec 16, 2013, 03.59AM IST PANAJI: January 2014 promises to be an interesting month for Goa, especially where its Portuguese ties are concerned. Just days before the Lusofonia Games begin, Goa is set to host a business conference that will bring together business leaders from the Lusophone (Portuguese-speaking) countries. A two-day international congress titled 'India and the Lusophone Market' is scheduled to take place on January 14 and 15, 2014, that will give Indian corporates the opportunity to interact with industry leaders from Lusophone countries. "The world being a global village and there being over 250 million Portuguese speakers in the world, the congress aims at being a common platform of the Portuguese speaking countries of the world. India, because of Goa's ties with the Portuguese world, can take advantage of this," says Lusophone Society of Goa (LSG) president Aurobindo Xavier. Organized by LSG in collaboration with Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), Institute of Asian Studies (IdEA ) and Friendship Association Portugal-India (AAPI), the conference will focus on India and the markets of the Portuguese-speaking countries of Angola, Brazil, Cape Verde, East Timor, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Portugal, Sao Tome and Principe, and the Chinese special administrative region (SAR) of Macau. Xavier adds that the conference will give established and budding entrepreneurs from Portuguese-speaking countries and from India a platform where they can meet and discuss to "learn about the possibilities of exchange of goods and services". As Portugal had a major presence in Africa, Xavier says that it is in this continent that India can expand its business ties by looking at the Lusophone market. -

The Lusophone Potential of Strategic Cooperation Between Portugal and India

The Lusophone Potential of Strategic Cooperation between Portugal and India Constantino Xavier PhD candidate, South Asian Studies, The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Washington D.C. Non-resident researcher at the Portuguese Institute of International Relations, Lisbon. Abstract Resumo Despite their starkly different profiles and global trajec- O Potencial da Lusofonia na Cooperação Estraté- tories, Portugal and India can develop a strong partner- gica entre Portugal e a Índia ship by focusing on cooperation in the Portuguese- speaking countries, where Lisbon continues to enjoy Para além de significativas diferenças em termos disproportionally high influence and where India seeks do seu peso e perfil internacional, Portugal e a to pursue its new external interests. This paper reviews Índia partilham um interesse conjunto pelo poten- the development and convergence in bilateral relations, cial dos países lusófonos, onde Lisboa continua a explores India’s rising interest and engagement with the gozar de uma influência preponderante e Nova lusosphere, and forwards specific recommendations for Deli procura expandir os seus novos interesses geo- Lisbon and New Delhi to tap into the political, economic, económicos. Este artigo analisa o desenvolvimento strategic and cultural potential of cooperation in the das relações bilaterais luso-indianas e argumenta Portuguese-speaking world. que as políticas externas de ambos os países con- vergem agora nas regiões de expressão e influência portuguesa. Para explorar o potencial deste cruza- mento de interesses, são apresentadas várias reco- mendações e iniciativas concretas nas áreas do diá- logo político, económico, estratégico e cultural. 2016 N.º 142 87 Nação e Defesa pp. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Burnout Set to Thrill at BIC Friday Night

SPORTS Thursday, September 10, 2015 29 RAWALPINDIMuhammad Azam/DTNN EXPRESS Manama ricket fans are eagerly waiting to welcome former Pakistani cricketer ShoaibC Akhtar, nicknamed ‘Rawalpindi Express’, to Busaiteen ground on Friday. He will be the chief guest for the final This Month match of cricket tournament organised by Bahrain Cricket League (BCL) in concert Sep 18 with Coca Cola Bottling Company. The Diplomat Radisson match is scheduled to begin at 3pm. Speaking to DT News, Head of Chancery Blu Hotel Pakistan Embassy Muhammad Ahad Manama said the Embassy would welcome Shoaib Akhtar on his maiden visit to the Kingdom. General Secretary Bahrain Cricket League (BCL) Mujtaba Nazir said it was for the first time in the cricketing history of Bahrain that such an event of this magnitude is going to happen. He also said they were trying to bring more cricket stars from different countries to Bahrain. Commenting on BCL’s efforts to develop cricket in Bahrain, he remarked: “If Oman can qualify for T20 World Cup IN 2016, why not Bahrain?” Liverpool FC legend The winners in the BCL tournament Robbie Fowler final will be awarded BD1,000 prize, while the runners-up will receive BD500. More events will be held throughout the cricket season in Bahrain till April Man Utd FC veteran 2016. More details available at: www. Lee Sharpe BAHRAIN spritecricketstars.com. Burnout set to thrill at BIC friday night DT News Network offers a unique kind of thrill from 4pm onwards at car parks per person. There will also be a Manama including the sight of rapidly one and two. -

Dear Aspirant with Regard

DEAR ASPIRANT HERE WE ARE PRESENTING YOU A GENRAL AWERNESS MEGA CAPSULE FOR IBPS PO, SBI ASSOT PO , IBPS ASST AND OTHER FORTHCOMING EXAMS WE HAVE UNDERTAKEN ALL THE POSSIBLE CARE TO MAKE IT ERROR FREE SPECIAL THANKS TO THOSE WHO HAS PUT THEIR TIME TO MAKE THIS HAPPEN A IN ON LIMITED RESOURCE 1. NILOFAR 2. SWETA KHARE 3. ANKITA 4. PALLAVI BONIA 5. AMAR DAS 6. SARATH ANNAMETI 7. MAYANK BANSAL WITH REGARD PANKAJ KUMAR ( Glory At Anycost ) WE WISH YOU A BEST OF LUCK CONTENTS 1 CURRENT RATES 1 2 IMPORTANT DAYS 3 CUPS & TROPHIES 4 4 LIST OF WORLD COUNTRIES & THEIR CAPITAL 5 5 IMPORTANT CURRENCIES 9 6 ABBREVIATIONS IN NEWS 7 LISTS OF NEW UNION COUNCIL OF MINISTERS & PORTFOLIOS 13 8 NEW APPOINTMENTS 13 9 BANK PUNCHLINES 15 10 IMPORTANT POINTS OF UNION BUDGET 2012-14 16 11 BANKING TERMS 19 12 AWARDS 35 13 IMPORTANT BANKING ABBREVIATIONS 42 14 IMPORTANT BANKING TERMINOLOGY 50 15 HIGHLIGHTS OF UNION BUDGET 2014 55 16 FDI LLIMITS 56 17 INDIAS GDP FORCASTS 57 18 INDIAN RANKING IN DIFFERENT INDEXS 57 19 ABOUT : NABARD 58 20 IMPORTANT COMMITTEES IN NEWS 58 21 OSCAR AWARD 2014 59 22 STATES, CAPITAL, GOVERNERS & CHIEF MINISTERS 62 23 IMPORTANT COMMITTEES IN NEWS 62 23 LIST OF IMPORTANT ORGANIZATIONS INDIA & THERE HEAD 65 24 LIST OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AND HEADS 66 25 FACTS ABOUT CENSUS 2011 66 26 DEFENCE & TECHNOLOGY 67 27 BOOKS & AUTHOURS 69 28 LEADER”S VISITED INIDIA 70 29 OBITUARY 71 30 ORGANISATION AND THERE HEADQUARTERS 72 31 REVOLUTIONS IN AGRICULTURE IN INDIA 72 32 IMPORTANT DAMS IN INDIA 73 33 CLASSICAL DANCES IN INDIA 73 34 NUCLEAR POWER