Arxiv:1709.01219V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exodata: a Python Package to Handle Large Exoplanet Catalogue Data

ExoData: A Python package to handle large exoplanet catalogue data Ryan Varley Department of Physics & Astronomy, University College London 132 Hampstead Road, London, NW1 2PS, United Kingdom [email protected] Abstract Exoplanet science often involves using the system parameters of real exoplanets for tasks such as simulations, fitting routines, and target selection for proposals. Several exoplanet catalogues are already well established but often lack a version history and code friendly interfaces. Software that bridges the barrier between the catalogues and code enables users to improve the specific repeatability of results by facilitating the retrieval of exact system parameters used in an arti- cles results along with unifying the equations and software used. As exoplanet science moves towards large data, gone are the days where researchers can recall the current population from memory. An interface able to query the population now becomes invaluable for target selection and population analysis. ExoData is a Python interface and exploratory analysis tool for the Open Exoplanet Cata- logue. It allows the loading of exoplanet systems into Python as objects (Planet, Star, Binary etc) from which common orbital and system equations can be calculated and measured parame- ters retrieved. This allows researchers to use tested code of the common equations they require (with units) and provides a large science input catalogue of planets for easy plotting and use in research. Advanced querying of targets are possible using the database and Python programming language. ExoData is also able to parse spectral types and fill in missing parameters according to programmable specifications and equations. Examples of use cases are integration of equations into data reduction pipelines, selecting planets for observing proposals and as an input catalogue to large scale simulation and analysis of planets. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

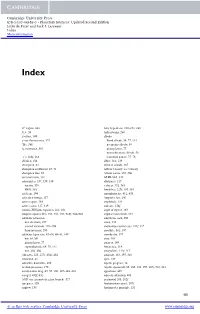

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09161-0 - Planetary Sciences: Updated Second Edition Imke de Pater and Jack J. Lissauer Index More information Index D region, 263 Airy hypothesis, 252–253, 280 I/F,59 Aitken basin, 266 β-effect, 109 albedo γ -ray fluorescence, 571 Bond albedo, 58, 77, 144 3He, 386 geometric albedo, 59 ν6 resonance, 581 giant planets, 77 monochromatic albedo, 58 ’a’a, 168f, 168 terrestrial panets, 77–78 ablation, 184 albite, 162, 239 absorption, 67 Aleutan islands, 167 absorption coefficient, 67, 71 Alfven´ velocity; see velocity absorption line, 85 Alfven´ waves, 291, 306 accretion zone, 534 ALH84001, 342 achondrites, 337, 339, 358 allotropes, 217 eucrite, 339 α decay, 352, 365 HED, 358 Amalthea, 227f, 455, 484 acid rain, 194 amorphous ice, 412, 438 activation energy, 127 Ampere’s law, 290 active region, 283 amphibole, 154 active sector, 317, 319 andesite, 156f Adams–Williams equation, 261, 281 angle of repose, 163 adaptive optics (AO), 104, 194, 494, 568f, 568–569 angular momentum, 521 adiabatic invariants anhydrous rock, 550 first invariant, 297 anion, 153 second invariant, 297–298 anomalous cosmic rays, 311f, 312 third invariant, 298 anorthite, 162, 197 adiabatic lapse rate, 63–64, 80–81, 149 anorthosite, 197 dry, 64, 80 ansa, 459 giant planets, 77 antapex, 189 superadiabatic, 64, 70, 111 Antarctica, 214 wet, 101–102 anticyclone, 111f, 112 Adrastea, 225, 227f, 454f, 484 antipode, 183, 197, 316 advection, 61 apex, 189 advective derivative, 108 Apollo program, 16 aeolian processes, 173 Apollo spacecraft, 95, 185, 196–197, 267f, 316, 341 aerodynamic drag, 49, 55, 102, 347–348, 416 apparition, 407 aerogel, 432f, 432 aqueous alteration, 401 AGB star (asymptotic giant branch), 527 arachnoid, 201, 202f agregates, 528 Archimedean spiral, 287f airglow, 135 Archimedes principle, 251 625 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09161-0 - Planetary Sciences: Updated Second Edition Imke de Pater and Jack J. -

Les Exoplanètes

LESLES EXOPLANEXOPLANÈÈTESTES Introduction Les différentes méthodes de détection Le télescope spatial Kepler Résultats et typologie GAP 47 • Olivier Sabbagh • Avril 2016 Les exoplanètes I Introduction Une exoplanète, ou planète extrasolaire, est une planète située en dehors du système solaire, c’est à dire une planète qui est en orbite autour d’une étoile autre que notre Soleil. L'existence de planètes situées en dehors du Système solaire est évoquée dès le XVIe siècle par Giordano Bruno. Ce moine novateur et provocateur du XVI° siècle a eu des intuitions foudroyantes qu’il assénait avec force et conviction, en opposition farouche contre le dogme du géocentrisme qui prévalait depuis Aristote et Ptolémée. Son entêtement lui vaudra le bûcher pour hérésie en 1600. Voir le paragraphe qui lui est consacré dans notre document « une histoire de l’astronomie ». Dès 1584 (Le Banquet des cendres), Bruno adhère, contre la cosmologie d'Aristote, à la cosmologie de Copernic (1543), à l'héliocentrisme : double mouvement des planètes sur elles-mêmes et autour du Soleil, au centre. Mais Bruno va plus loin : il veut renoncer à l'idée de centre : « Il n'y a aucun astre au milieu de l'univers, parce que celui-ci s'étend également dans toutes ses directions ». Chaque étoile est un soleil semblable au nôtre, et autour de chacune d'elles tournent d'autres planètes, invisibles à nos yeux, mais qui existent. « Il est donc d'innombrables soleils et un nombre infini de terres tournant autour de ces soleils, à l'instar des sept « terres » [la Terre, la Lune, les cinq planètes alors connues : Mercure, Vénus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturne] que nous voyons tourner autour du Soleil qui nous est proche ». -

![[Final] Origin of Oceans and Waterworlds](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2625/final-origin-of-oceans-and-waterworlds-1152625.webp)

[Final] Origin of Oceans and Waterworlds

Origin of oceans and waterworlds Boris Pestoni, Vytenis Šumskas University of Zürich AST 202 The Universe: Contents, Origin, Evolution and Future March 22, 2016 S Contents S Origin of water on Earth S How did the oceans form? S States of matter of water S Is water a peculiarity of the Earth? S Extreme worlds: ice planets and ocean planets Water on Earth S ~71% of the Earth’s surface is covered with water. Water on Earth S Only 0,02% - 0,06% of our planet’s total mass is water. S Nonetheless, Earth is called “The blue planet”. Oceans on Earth S The age of Earth’s oceans is estimated to be nearly the same as the age of Earth: 4 - 4,4 billion years. Oceans on Earth S The planet cooled. S It became covered in gas. Oceans on Earth S The longest rain in the history of Earth. S Eventually water gathered in the deepest parts of surface. Other sources of water S ≥50% of Earth’s water came from outer space. Water in asteroids S How do we even know it? States of matter of water Water in the universe Until now we have found water in the following objects / regions: Out of Proto_ Rings the planetary disk Asteroid Comets of Mars Moon Earth Milky of the Milky belt Saturn Way Way Water of ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ crystallization Water ice ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Liquid water ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Steam ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Supercritical ✓ water Overview of the Solar System Imbalance of water on planets S The reason that there is clearly more liquid water on the Earth than on the other rocky planets of the Solar System is, until now, not completely understood. -

Discoveries by Astronomer Thomas Scott Zolotor

Discoveries by Astronomer Thomas Scott Zolotor July 30, 2013 at 12:38pm https://www.facebook.com/notes/tom-freethesouls-zolotor/discoveries-by-astronomer-thomas-scott-z olotor/10151738488524144 THOMAS ZOLOTOR IS A FINANCIAL POLICE® DEPUTY AGENT HE ALSO A SEA CAPTAIN AND ORDINATED MINISTER AS WELL AS AN ASTRONOMER. HE SOMETIMES GOES BY CAPTAIN FREE THE SOULS. Astronomer, Thomas Scott Zolotor, is helping to map and study parts of Mars, Mercury, Vesta and the Moon. Thomas is also studying how galaxies form and has classified and discovered never before seen galaxies. He is searching for gravitational waves around pulsars, and has produced a better understanding of how the Milky Way formed. Thomas is seeking to better define dark matter as well as how the universe formed after the big bang. In his studies, Thomas searches for planets around other star systems. In 1991, Thomas found an asteroid. He has discovered several asteroids and stellar clusters to date.Captain Thomas Zolotor took part in the Andromeda Project which produce the largest catalog of star clusters known in any spiral galaxy. He was one of the very first to find undiscovered stellar clusters in this program. He found a stellar cluster that looks like the letter"N" and another that looks like the number 2. He has discovered many more stellar clusters in the galaxy Andromeda. He has published numerous theories about the universe that are supported by recent research. 1. Captain Zolotor discovered never before seen galaxies. 2. Captain Zolotor discovered never before seen stellar clusters and was involved in helping to make the largest ever catalog of stellar clusters. -

Part 1: the 1.7 and 3.9 Earth Radii Rule

Hi this is Steve Nerlich from Cheap Astronomy www.cheapastro.com and this is What are exoplanets made of? Part 1: The 1.7 and 3.9 earth Radii rule. As of August 2016, the current count of confirmed exoplanets is up around 3,400 in 2,617 systems – with 590 of those systems confirmed to be multiplanet systems. And the latest thinking is that if you want to understand what exoplanets are made of you need to appreciate the physical limits of planet-hood, which are defined by the boundaries of 1.7 and 3.9 Earth radii . Consider that the make-up of an exoplanet is largely determined by the elemental make up of its protoplanetary disk. While most material in the Universe is hydrogen and helium – these are both tenuous gases. In order to generate enough gravity to hang on to them, you need a lot of mass to start with. So, if you’re Earth, or anything up to 1.7 times the radius of Earth – you’ve got no hope of hanging onto more than a few traces of elemental hydrogen and helium. Indeed, any exoplanet that’s less than 1.7 Earth radii has to be primarily composed of non-volatiles – that is, things that don’t evaporate or blow away easily – to have any chance of gravitationally holding together. A non-volatile exoplanet might be made of rock – which for our Solar System is a primarily silicon/oxygen based mineral matrix, but as we’ll hear, small sub-1.7 Earth radii exoplanets could be made of a whole range of other non-volatile materials. -

Jeu Complet Recto

$* ) & !'! # 6 0 < ! 7* )) 4 4 $* & " * : * @ 1 * * 0* 4 ? * ) ) : 7 6 ! ! * 6! * ! *" ( 7 * ! # ! 0A * ) 8 0 ! $ ! ( ) ! & 8 B/CCD;EF/ GDC/<F6H;/C # & # ) 6 ID;5D;7 ! /*I * ; 8 4<J9 ' * '! ! ' +,-."/ + # , * $ ! ! * * ! " ! " #!$!% & '#!$!%! 7** ! # $ ! - % ! * ' !'.; ) &&$ ' ' 4 ! 5 & ' ' :)) * ( '' * 7 < #% ' ' * #) * + = ,- ) . 0 ! 4 < / ) ) $ * 8 3> $ 0* 01##'2 '- 0. 3'2 0 ) 1 )' -$ . % '45' -! . '5' -! '2 ' 0 . ) * ! !" '2)' 0 0 6 * $ * ! * 7 $ '45' * 0 )) * ! / * '5' ! ? ! * ! 1 ! / 0 * ! 0 8 * ) ! )) * #!% ! 9 * 6 * )) 1 ! ! # ) / * ) 0 * ! ) @ 0 9 ! 0 0 ! " )* 6 -

De Natura Rerum: Exoplanets and Exoearths Pierre Léna Que L’Homme Contemple La Nature Dans Sa Haute Et Pleine Majesté… Que La Terre Lui Paraisse Comme Un Point

De Natura Rerum: Exoplanets and ExoEarths Pierre Léna Que l’homme contemple la nature dans sa haute et pleine majesté… que la Terre lui paraisse comme un point. Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) Pensées Introduction At the 2004 Plenary Session of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences on Paths of Discovery, I presented a paper with the title The case of exoplanets [Léna 2005]. It was then close to the 10th anniversary of the discovery of the first exoplanet in 1995. There is no point in repeating here this paper. But in the last decade, the discoveries on this subject have been so considerable that, the 20th anniversary coming, it is worth addressing the topic again. During the first decade 1995-2004, only 133 exoplanets had been discovered by an indirect method, and the first direct image of an exoplanet was not even confirmed. Today in our Galaxy containing the Earth, statistics begin to indicate that on average every star has a planet, which means over 100 billions of exoplanets for this galaxy alone, of which nearly 2000 are now identified and more or less characterized. How does the subject of exoplanets relate with the Evolving concepts of nature, the title of this Plenary Session? In the 2005 paper, I recalled the long history of a quest which began metaphysically with Democritus, was disputed theologically during the Middle Age, provided phantasies to poets and writers, until it emerged as a scientific problem, to be addressed with the investigative methods of astronomy during the 19th century. Along this path, Giordano Bruno, who expressed ideas close to Lucretius’s ones, was condemned to the fire for multiple reasons, including this one. -

Zone Eight-Earth-Mass Planet K2-18 B

LETTERS https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-019-0878-9 Water vapour in the atmosphere of the habitable- zone eight-Earth-mass planet K2-18 b Angelos Tsiaras *, Ingo P. Waldmann *, Giovanna Tinetti , Jonathan Tennyson and Sergey N. Yurchenko In the past decade, observations from space and the ground planet within the star’s habitable zone (~0.12–0.25 au) (ref. 20), with have found water to be the most abundant molecular species, effective temperature between 200 K and 320 K, depending on the after hydrogen, in the atmospheres of hot, gaseous extrasolar albedo and the emissivity of its surface and/or its atmosphere. This planets1–5. Being the main molecular carrier of oxygen, water crude estimate accounts for neither possible tidal energy sources21 is a tracer of the origin and the evolution mechanisms of plan- nor atmospheric heat redistribution11,13, which might be relevant for ets. For temperate, terrestrial planets, the presence of water this planet. Measurements of the mass and the radius of K2-18 b 22 is of great importance as an indicator of habitable conditions. (planetary mass Mp = 7.96 ± 1.91 Earth masses (M⊕) (ref. ), plan- 19 Being small and relatively cold, these planets and their atmo- etary radius Rp = 2.279 ± 0.0026 R⊕ (ref. )) yield a bulk density of spheres are the most challenging to observe, and therefore no 3.3 ± 1.2 g cm−1 (ref. 22), suggesting either a silicate planet with an 6 atmospheric spectral signatures have so far been detected . extended atmosphere or an interior composition with a water (H2O) Super-Earths—planets lighter than ten Earth masses—around mass fraction lower than 50% (refs. -

→ Space for Europe European Space Agency

number 150 | May 2012 bulletin → space for europe European Space Agency The European Space Agency was formed out of, and took over the rights and The ESA headquarters are in Paris. obligations of, the two earlier European space organisations – the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO) and the European Launcher Development The major establishments of ESA are: Organisation (ELDO). The Member States are Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the ESTEC, Noordwijk, Netherlands. Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Canada is a Cooperating State. ESOC, Darmstadt, Germany. In the words of its Convention: the purpose of the Agency shall be to provide for ESRIN, Frascati, Italy. and to promote, for exclusively peaceful purposes, cooperation among European States in space research and technology and their space applications, with a view ESAC, Madrid, Spain. to their being used for scientific purposes and for operational space applications systems: Chairman of the Council: D. Williams → by elaborating and implementing a long-term European space policy, by Director General: J.-J. Dordain recommending space objectives to the Member States, and by concerting the policies of the Member States with respect to other national and international organisations and institutions; → by elaborating and implementing activities and programmes in the space field; → by coordinating the European space programme and national programmes, and by integrating the latter progressively and as completely as possible into the European space programme, in particular as regards the development of applications satellites; → by elaborating and implementing the industrial policy appropriate to its programme and by recommending a coherent industrial policy to the Member States. -

Brave New Worlds?

PUBLISHED: 4 APRIL 2017 | VOLUME: 1 | ARTICLE NUMBER: 0113 editorial Brave new worlds? Twenty-five years ago, the detection of the first extrasolar planets opened up an area of research that has fascinated both researchers and the general public alike. Are we alone in the Universe? This oft-posed a brown dwarf? And would 51 Pegasi b be TRAPPIST-1b Pb = 1.51 d question is a loaded one. Given the billions able to sustain an atmosphere? In order to 1.00 of stars in our own Galaxy, surely life study exoplanet atmospheres, radial velocity TRAPPIST-1c P = 2.42 d must exist somewhere beyond our planet. measurements are not enough. The planet c And what exactly do we mean by life? For has to transit across its star. TRAPPIST-1d Pd = 4.05 d Earth-based lifeforms that we know, liquid The first such transiting exoplanet was 0.98 water and sufficient gravity to hold onto an observed in 1999. A slight dip in the light TRAPPIST-1e Pe = 6.10 d atmosphere are required, at the very least. curve was measured as part of the star was TRAPPIST-1f Pf = 9.20 d These conditions define the ideal distance eclipsed. From the change in the measured 0.96 Relative brightness Relative (the ‘Goldilocks’ zone of habitability) starlight, we get the mass ratio between TRAPPIST-1g Pg = 12.35 d between a planet and its star as well as a the planet and the star. Molecules in a TRAPPIST-1h Ph = 14−25 d minimum planetary mass. On the occasion of transiting planet’s atmosphere absorb the 0.94 the twenty-fifth anniversary of the discovery light emitted by the star behind it, so we of the first extrasolar planets, we look back can glean information on the composition –0.04 –0.02 0.00 0.02 0.04 and ahead. -

Annual Report 2011

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ON THE COVER: HEADQUARTERS LOCATION: FY2011 Ace summit operations team Kamuela, Hawai’i, USA Number of Full Time members, from left: Arnold Employees: 115 Matsuda, John Baldwin and MANAGEMENT: Mike Dahler, focus their California Association for Number of Observing attention to removing a Research in Astronomy Astronomers FY2011: 464 single segment from the PARTNER INSTITUTIONS: Number of Keck Science Keck Telescope primary California Institute of Investigations: 400 mirror in the first major step Technology (CIT/Caltech), in the segment recoating Number of Refereed Articles process. University of California (UC), FY2011: 278 National Aeronautics and Fiscal Year begins October 1 BELOW: Space Administration (NASA) The newly commissioned Federal Identification Keck I Laser penetrates the OBSERVATORY DIRECTOR: Number: 95-3972799 night sky from the majestic Taft E. Armandroff landscape of Mauna Kea. DEPUTY DIRECTOR: The laser is part of Keck’s Hilton A. Lewis world leading adaptive optics systems, a technology used to remove the effects of turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere and provides unprecedented image clarity of cosmic targets near and distant. VISION A world in which all humankind is inspired and united by the pursuit of knowledge of the infinite CONTENTS variety and richness of the Universe. Director’s Report . 3 Cosmic Visionaries . 6 Science Highlights . 8 MISSION Finances . 16 To advance the frontiers of astronomy and share Philanthropic Support . .18 our discoveries, inspiring the imagination of all. Reflections . .20 Education & Outreach . .22 Observatory Groundbreaking: 1985 Honors & Recognition . .26 First light Keck I telescope: 1992 Science Bibliography . 28 First light Keck II telescope: 1996 DIRECTOR’s REPORT Taft E.