Crystals in the Public Domain David Fagundes [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advertising and Public Relations Law

Advertising and Public Relations Law Addressing a critical need, Advertising and Public Relations Law explores the issues and ideas that affect the regulation of advertising and public relations speech. Coverage includes the categorization of different kinds of speech afforded varying levels of First Amendment protection; court-created tests for laws and reg- ulations of speech; and non-content-based restrictions on speech and expression. Features of this edition include: • A discussion in each chapter of new-media implications • Extended excerpts from major court decisions • Appendices providing — a chart of the judicial system — a summary of the judicial process — an overview of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms — the professional codes for media industry and business associations, including the American Association of Advertising Agencies, the Public Relations Society of America and the Society of Professional Journalists • Online resources for instructors. The volume is developed for upper-level undergraduate and graduate students in media, advertising and public relations law or regulation courses. It also serves as an essential reference for advertising and public relations practitioners. Roy L. Moore is professor of journalism and dean of the College of Mass Communication at Middle Tennessee State University. He holds a Ph.D. in mass communication from the University of Wisconsin and a juris doctorate from the Georgia State University College of Law. Carmen Maye is a South Carolina-based lawyer and an instructor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of South Carolina, where she teaches courses in media law and advertising. Her undergraduate degree is from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

9781317587255.Pdf

Global Metal Music and Culture This book defines the key ideas, scholarly debates, and research activities that have contributed to the formation of the international and interdisciplinary field of Metal Studies. Drawing on insights from a wide range of disciplines including popular music, cultural studies, sociology, anthropology, philos- ophy, and ethics, this volume offers new and innovative research on metal musicology, global/local scenes studies, fandom, gender and metal identity, metal media, and commerce. Offering a wide-ranging focus on bands, scenes, periods, and sounds, contributors explore topics such as the riff-based song writing of classic heavy metal bands and their modern equivalents, and the musical-aesthetics of Grindcore, Doom and Drone metal, Death metal, and Progressive metal. They interrogate production technologies, sound engi- neering, album artwork and band promotion, logos and merchandising, t-shirt and jewelry design, and the social class and cultural identities of the fan communities that define the global metal music economy and subcul- tural scene. The volume explores how the new academic discipline of metal studies was formed, while also looking forward to the future of metal music and its relationship to metal scholarship and fandom. With an international range of contributors, this volume will appeal to scholars of popular music, cultural studies, social psychology and sociology, as well as those interested in metal communities around the world. Andy R. Brown is Senior Lecturer in Media Communications at Bath Spa University, UK. Karl Spracklen is Professor of Leisure Studies at Leeds Metropolitan Uni- versity, UK. Keith Kahn-Harris is honorary research fellow and associate lecturer at Birkbeck College, UK. -

Suzy & Los Quat T

Fecha Salida: 27 de Septiembre de 2011 Singles Recomendados: 7. I.O.U. (I Owe Yo u ) 6. In My Dreams Again 1. Freak Out 5. Kick Ass SUZY & LOS QUAT T R O HANK Lista de canciones: Wow, esto sí que es tomar algo negativo y convertirlo en positivo. 1. Freak Out 2. Don’t Wanna Talk About It En marzo de 2009, Suzy & Los Quattro perdieron a su gran amigo y road- ie HANK. Este hecho les catapultó en un episodio que han capturado 3. Move On como si se tratara de una película en audio. Dudo en utilizar el término 4. The Quiet Man "ópera rock" ya que este disco incluye grandes dosis de "roll". 5. Kick Ass 6. In My Dreams Again Además, aparte de tener que enfrentarse a la muerte de un amigo excep- 7. I.O.U. (I Owe Yo u ) cional, el proceso de aceptación tuvo múltiples subidas y bajadas. Todas 8. Love Never Dies ellas están documentadas aquí, tomando forma tras algo así como una 9. You Angel Yo u colisión entre lo más florido del punk de la costa este y el glorioso pop 10. Still Mad About Yo u californiano. 11. The Goodbye Song Hoy en día se vierten ríos de tinta sobre lo maravillosas que son ciertas bandas y artistas. La mayor parte es palabrería, pero tienen que vender- Puntos de interés: los de alguna forma. Yo levanto mi mano - estoy quizás algo sesgado pero - Producido por Robbie Rist (The Rubinoos, uno ha de intentar ser objetivo. Hay momentos en los que, para manten- Steve Barton, The Mockers) y grabado en los er algún tipo de credibilidad, tal sesgo debe ser mantenido a distancia ya estudios Musiclan (Figuere s ) que lo contrario perjudicaría tanto a la banda sobre la que se escribe como al individuo que testifica sobre ellos. -

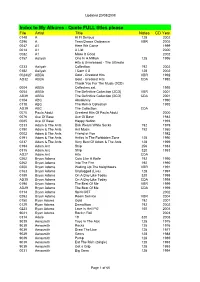

Album Backup List

Updated 20/08/2008 Index to My Albums - Quote FULL titles please File Artist Title Notes CD Year 0148 A Hi Fi Serious 128 2002 0296 A Teen Dance Ordinance VBR 2005 0047 A1 Here We Come 1999 0014 A1 A List 2000 0082 A1 Make It Good 2002 0157 Aaliyah One In A Million 128 1996 Hits & Unreleased - The Ultimate 0233 Aaliyah Collection 192 2002 0182 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 128 2002 0024/27 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits VBR 1992 AD32 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits CDA 1992 Thank You For The Music (3CD) 0004 ABBA Collectors set 1995 0054 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) VBR 2001 AB39 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) CDA 2001 0104 ABC Absolutely 1990 0118 ABC The Remix Collection 1993 AD39 ABC The Collection CDA 0070 Paula Abdul Greatest Hits Of Paula Abdul 2000 0076 Ace Of Base Ace Of Base 1983 0085 Ace Of Base Happy Nation 1993 0233 Adam & The Ants Dirk Wears White Socks 192 1979 0150 Adam & The Ants Ant Music 192 1980 0002 Adam & The Ants Friend or Foe 1982 0191 Adam & The Ants Antics In The Forbidden Zone 128 1990 0237 Adam & The Ants Very Best Of Adam & The Ants 128 1999 0194 Adam Ant Strip 256 1983 0315 Adam Ant Strip 320 1983 AD27 Adam Ant Hits CDA 0262 Bryan Adams Cuts Like A Knife 192 1990 0262 Bryan Adams Into The Fire 192 1990 0200 Bryan Adams Waking Up The Neighbours VBR 1991 0163 Bryan Adams Unplugged (Live) 128 1997 0189 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today 320 1998 AD30 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today CDA 1998 0198 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me VBR 1999 AD29 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me CDA 1999 0114 Bryan Adams Spirit OST 2002 0293 Bryan Adams -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) This is Pop…XTC (3/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Airport…Motors (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) Roxanne…The Police (2/79) Lucky Number (slavic dance version)…Lene Lovich (3/79) Good Times Roll…The Cars (3/79) Dance -

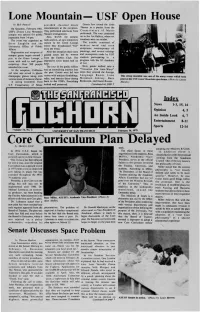

Core Curriculum Plan Delayed

Lone Mountain— USF Open House by Rob Patacsil provided classical music Guests first toured the Little Theater as a pianist from the On Saturday, February 10th, entertainment at the reception. Conservatory of Music USFs 23-acre Lone Mountain They performed selections from performed. The tour continued campus was opened for public Mozart arrangements. on to the Art Gallery, where art inspection from 3-6 pm. Also, KUSF, the campus creations were on exhibit. The event was organized by radio station, set up a temporary Steve Laughlin and the station in the Green Lounge The exhibit consisted of University Office of Public where they broadcasted "live" modern metal and neon Affairs. from the event. sculptures, contemporary oil Registration and reception of After the reception there were paintings, and several etchings campus guests began around 3 guided tours led by women and monoprints made by USF p.m. in the Green Lounge, a from the Embers Club. The students participating in a room with wall to wall green impressive tours lasted half an program with the SF Academy carpeting. Over 500 people hour. of Art. attended the event. The tour of the gothic edifice Next, guests walked into a At the reception, California was an astonishing journey into "Victorian Era time-Warp" red wine was served in plastic the past. Guests were led into when they entered the Foreign champagne glasses along with rooms with antique furnishings, Language Room. Lone This string ensemble was one of the many events which took various kinds of domestic cheese. relics, and interior decor dating Mountain Library, Rare place at the USF-Lone Mountain open house. -

Lot 1 12 X ROLLING STONES VINYL LP RECORDS. All Presented Here in VG++/Ex Conditions with Titles As Follows: - Still Life X 2 - Some Girls - the Best Of

Cottees Auctions - Rock & Pop Memorabilia in conjunction with Modern Interiors & Collectables. - Starts 09 Nov 2019 Lot 1 12 x ROLLING STONES VINYL LP RECORDS. All presented here in VG++/Ex conditions with titles as follows: - Still Life x 2 - Some Girls - The Best Of... - Tattoo You - Under Cover - It's Only Rock 'n' Roll - Love You Live - Steel Wheels - Black & Blue - Emotional Rescue plus a zipped copy of Sticky Fingers. All albums released on the Rolling Stones Label. Estimate: 80 - 100 Fees: 21.60% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 25.2% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 2 PINK FLOYD ALBUMS X 8. Super quality set of records here from The Floyd kicking of with 'Wish You Were Here' on a blue colour pressed German Harvest 1C 064 96 918 - 'Meddle' on Harvest SHVL 795 - 'Animals' on SHVL 815 - 'A Nice Pair' on SHDW 403 - 'A Saucerful Of Secrets' on Fame FA 3163 - 'Relics' on MFP 50397 - 'The Wall' (With Booklet) on SHDW 911. The last album is a copy of 'Wish You Were Here' on SHVLP 814 complete with it's black plastic outer sleeve still intact. All records are in VG++/Ex condition. Estimate: 80 - 120 Fees: 21.60% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 25.2% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 3 ROLLING STONES SELECTION OF 8 VINYL LP RECORDS. This set consists of originals and reissues. The following 3 albums are reissues starting with a Holland press of Beggars Banquet on Decca 6835113 - Out Of Our Heads on Decca SKL 4733 & Rolling Stones No. -

WEA, Warner Music, 1982–1992

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS WEA RECORDS / WARNER MUSIC 1982 to 1992 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER JULY 2020 WEA / WARNER, 1982–1992 WARNER BROS. 45’S 7-29998 ONE HELLO / THAT’S HOW HEARTACHES ARE MADE RANDY CRAWFORD 7.82 7-29996 HOW CAN YOU LOVE ME / STILL NOT SATISFIED AMBROSIA 5.82 7-29987 LOOK WHO’S LONELY NOW RANDY CRAWFORD 9.82 7-29986 DANCING IN THE STREET / THE FULL BUG VAN HALEN 8.82 7-29974 SOMEWAY SOMEDAY / YOU’RE MY FAVOURITE WASTE OF TIME MARSHALL CRENSHAW 7.82 7-29966 HOLD ME / EYES OF THE WORLD FLEETWOOD MAC 6.82 7-29955 HE’S SO DULL / MAKE-UP VANITY 6 8.82 7-29941 JAGGED EDGE / STILL IN LOVE ALESSI 8.82 7-29933 I KEEP FORGETTIN’ / LOSIN’ END MICHAEL MCDONALD 8.82 7-29931 PEEK A BOO! / FIND OUT DEVO 11.82 7-29920 HUNGER PAINS / MORE HOPELESS KNOWLEDGE EYE TO EYE 11.82 7-29918 GYPSY / COOL WATER FLEETWOOD MAC 7.82 7-29908 NASTY GIRL / DRIVE ME WILD VANITY 6 11.82 0-29906 PEEK A BOO! (2 VERSIONS) / FIND OUT 12” DEVO 11.82 7-29900 I.G.Y. / WALK BETWEEN RAINDROPS DONALD FAGAN 11.82 7-29896 1999 / HOW COME U DON’T CALL ME ANYMORE PRINCE 11.82 7-29894 THERE SHE GOES AGAIN / THE USUAL THING MARSHALL CRENSHAW 11.82 7-29893 YOUR PRECIOUS LOVE / MONMOUTH COLLEGE FIGHT SONG RANDY CRAWFORD / AL JARREAU 11.82 7-29874 GUESS I’LL ALWAYS LOVE YOU / ROCK MY PLIMSOUL ROD STEWART 11.82 7-29873 WHY’D I HIRE A WINO TO DECORATE OUR HOME / HEARTBREAK AVENUE SUSAN PETERS 1.83 7-29864 WAKE UP MY LOVE / GREECE (INSTRUMENTAL) DARK HORSE GEORGE HARRISON 11.82 0-29858 NASTY GIRL / HE’S SO DULL / DRIVE ME WILD 12” VANITY 6 1982 7-29848 LOVE IN STORE / CAN’T -

What Happened to the Female Stars of Britpop?

Home News Sport Weather Shop Earth Travel Search Music Menu My Music What happened to the female stars of Britpop? By Fraser McAlpine Monday 13th November 2017 The indie bands that came to dominate Britpop emerged from a healthy alternative culture that was politically involved, progressive in outlook and inclusive of female input, from the alien techno of Björk to the literate blues of PJ Harvey. So it's a shame that now, 25 years after the formation of Elastica, that moment in popular culture is so often reduced to a boorish bunfight between blokes from the north (Oasis) and blokes from the south (Blur), or a testosterone-driven clash of classes. It was all of those things and several more complicated stories too, and nowhere near as male-dominated as it appears in the retelling. Here are seven bands whose contribution should not be overlooked. 1. Elastica [LISTEN] Justine Frischmann: Why I dropped music for art Elastica formed in mid-1992, when Justine Frischmann and Justin Welch decided they needed a group to reflect the interests of people like them. They made one album of sharp post-punk with lyrics confidently tackling erectile disfunction, scenesters and making out in cars, and it sold faster than any debut album since Definitely Maybe (a record it held for over 10 years). There followed a messy period, with band members leaving and arriving and a scrappy second album The Menace in 2000, after which the band split up. Guitarist Donna Matthews continues to make music under her own name, and works as a Christian missionary to the homeless. -

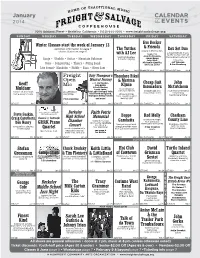

January CALENDAR of EVENTS

January CALENDAR 2014 of EVENTS 2020 Addison Street • Berkeley, California • (510) 644-2020 • www.freightandsalvage.org SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Eve Decker Winter Classes start the week of January 13 workshop information on page 7 & Friends The Tuttles acoustic dharma folk Box Set Duo classes & jams on page 8 substantial folk music with AJ Lee featuring by the co-founders of blazing bluegrass Jennifer Berezan, the popular roots band & soulful singing James Baraz, Banjo • ‘Ukulele • Guitar • Mountain Dulcimer Julie Wolf, featuring Michaelle Goerlitz, Jeff Pehrson Voice • Songwriting • Theory • String Band and Lisa Zeiler & Jim Brunberg Live Sound• Mandolin • Fiddle • Bass • Blues Jam $21 adv/$23 door Jan 2 $19 adv/$21 door Jan 3 $25 adv/$27 door Jan 4 Freight Suzy Thompson’s Theodore Bikel Open Musical Journey & Merima with Jim Kweskin, Cheap Suit John Geoff Mic Kate Brislin Kljuco & Jody Stecher, Serenaders McCutcheon Laurie Lewis, in conversation Muldaur vintage jazz and multi-instrumentalist master of American an adventure Evie Ladin & Allegra Yellin, with Sam Norich Blue Flame Stringband, inexpensive attire reinventing home-grown music every time songs & stories traditional artistry Thompson String Ticklers from Jewish music’s 7:30 showtime and more! leading light $25/$27 Jan 5 $5/$7 Jan 7 $21/$23 Jan 8 $34/$37 Jan 9 $26.50/$28.50 Jan 10 $28.50/$30.50 Jan 11 San francisco Chamber orchestra presents Berkeley Faith Petric Steve Seskin, High School Memorial Beppe Red Molly Chatham Craig Carothers, Classical -

New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 083, No 75, 12/17/1979." 83, 75 (1979)

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1979 The aiD ly Lobo 1971 - 1980 12-17-1979 New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 083, No 75, 12/ 17/1979 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1979 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 083, No 75, 12/17/1979." 83, 75 (1979). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1979/148 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1971 - 1980 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1979 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ·5-Q~ ~ Cc?JLs 3 7~~~ 7 '89 Urt~GW . .Oz.c. 17J r ct•'····a.1 ____ cop·3 New Mexico Monday, Qec$mber 17, 1979 The problems.in UN.M athletics The UNM men's basketball athletic dep!lrtment officials and basketball Coach Norm Ellen· program 'has been under in· s~rved federal search warrants on berger !ind Goldstein, in which vestigation since Sept. 25, when assist!lnt coach Manny Gold· Goldstein relates to Ellenberger Players' eligibility, the NCAA filed 57 allegations of stein. The l?Bl was after evidence the methods he used to change rules violations against the that players' transcripts bad t;he transcript. Lobos, and in th!:l last two been doctored so that the athletes The current status of the men's months controversy surrounding would be eligible to compete at basketball team is that assistant the team has intensified. -

A. Programs May Get

IS Kihn under . gay the naked eye dana have page 3 h' the e the lgter Father en to new t and Sonvs. fetus other han a. page 6 Registration IS, SO and said. bility priority tops ed by le out S artan Dail ringe senate debate by Lori Eickmann University since 1934 mIth, Serving San Jose State The Academic Senate debated at its first meeting pa rt- Monday on whether handicapped students, varsity rk at athletes, first semester Equal Opportunity Program photo by Mtke year The setting sun provides background for the St Joseph Church on South Mark 31 Street Gallegos students and student registration workers should receive priority Computer Assisted Registration i CAR )yees Debate failed to resolve questions over which student ins is groups should receive priority CAR registration, or whether any group should receive priority in both CAR Ming and walk-through registration. in to The recommendation was referred back to com- more mittee. Programs may get cut An amendment passed in May 1973, granted priority em," in walk-through registration to handicapped students, by Morgan Hampton Hobert W. Burns gave school deans a March 30 target date recognized professional and career programs and !nt of varsity athletes during the semester when their sports School deans can no longer delay the difficult job of to have program reviews in SJSU President Gail programs for the preparation of graduate study leading to de is were in season, new lower-division EOP students and determining which academic programs will get the axe. Fullerton's office. advanced degrees. student registration workers.