Sangh-Ghshi Dialects of (Zaar) Sayawa Communities Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE 1.0 PERSONAL DATA 1.1 Name: MUSA Nengak 1.2 Date of birth: 2nd February, 1983 1.3 Nationality: Nigerian 1.4 State of origin: Plateau 1.5 Local Government Area: Pankshin 1.6 Sex: Male 1.7 Marital Status: Married 1.8 Number Children: one(1) 1.9 Email: [email protected], [email protected] 1.10 Mobile phone number: +2348062646593, 07058749625 1.11 Permanent Home Address : Tudunwada –Yelwa, Sabongida Road, Shendam Local Government Area, Plateau State 1.12Contact Address : Behind new garage, Makurdi road, Lafia, Nasarawa State 2.0 Educational Institutions Attended With Graduation Dates 2015 - 2017 University of Ibadan, Oyo State 2008 – 2012 Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria 2008 Bolade Grammar School, Oshodi, Lagos 2007- 2008 Ali Tatari Ali Polytechnic Bauchi, School of General Studies 2005 Wet-Land Comprehensive College, Obadore, Lagoa 2005 Nigerian Air Force Officers Women Association (NAFOWA) ICT Centre 1992 - 1998 Faya Community Primary School 3.0 Education/ qualifications with specialization 2017 Masters in Petroleum Geology and Sedimentology 2012 Bachelor of Science degree in Geology (Second Class Lower) 2008 West Africa Senior School Certificate (WAEC) 2007 Interim Joint Matriculation Board (IJMB) certificate 2005 West Africa Senior School Certificate (WAEC) 2005 Diploma in computer studies 1998 First leaving School Certificate 4.0 Membership Of Scholarly Organization or Professional Body: Nigerian Mining and Geosciences Society ( NMGS) 5.0 Certifications: 2013 – 2014 Nigerian Youth Service Corp, Adamawa -

Inequality and Development in Nigeria Inequality and Development in Nigeria

INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA Edited by Henry Bienen and V. P. Diejomaoh HOLMES & MEIER PUBLISHERS, INC' NEWv YORK 0 LONDON First published in the United States of America 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. 30 Irving Place New York, N.Y. 10003 Great Britain: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Ltd. 131 Trafalgar Road Greenwich, London SE 10 9TX Copyright 0 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. ALL RIGIITS RESERVIED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria. Selections. Inequality and development in Nigeria. "'Chapters... selected from The Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria."-Pref. Includes index. I. Income distribution-Nigeria-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Nigeria- Economic conditions- Addresses. essays, lectures. 3. Nigeria-Social conditions- Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Bienen. Henry. II. Die jomaoh. Victor P., 1940- III. Title. IV. Series. HC1055.Z91516 1981 339.2'09669 81-4145 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA ISBN 0-8419-0710-2 AACR2 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents Page Preface vii I. Introduction 2. Development in Nigeria: An Overview 17 Douglas Riummer 3. The Structure of Income Inequality in Nigeria: A Macro Analysis 77 V. P. Diejomaoli and E. C. Anusion wu 4. The Politics of Income Distribution: Institutions, Class, and Ethnicity 115 Henri' Bienen 5. Spatial Aspects of Urbanization and Effects on the Distribution of Income in Nigeria 161 Bola A veni 6. Aspects of Income Distribution in the Nigerian Urban Sector 193 Olufemi Fajana 7. Income Distribution in the Rural Sector 237 0. 0. Ladipo and A. -

Legislative Control of the Executive in Nigeria Under the Second Republic

04, 03 01 AWO 593~ By AWOTOKUN, ADEKUNLE MESHACK B.A. (HONS) (ABU) M.Sc. (!BADAN) Thesis submitted to the Department of Public Administration Faculty of Administration in Partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of --~~·---------.---·-.......... , Progrnmme c:~ Petites Subventions ARRIVEE - · Enregistré sous lo no l ~ 1 ()ate :. Il fi&~t. JWi~ DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PUBLIC ADMIJISTRATION) Obafemi Awolowo University, CE\/ 1993 1le-Ife, Nigeria. 2 3 r • CODESRIA-LIBRARY 1991. CERTIFICATION 1 hereby certify that this thesis was prepared by AWOTOKUN, ADEKUNLE MESHACK under my supervision. __ _I }J /J1,, --- Date CODESRIA-LIBRARY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A work such as this could not have been completed without the support of numerous individuals and institutions. 1 therefore wish to place on record my indebtedness to them. First, 1 owe Professer Ladipo Adamolekun a debt of gratitude, as the persan who encouraged me to work on Legislative contrai of the Executive. He agreed to supervise the preparation of the thesis and he did until he retired from the University. Professor Adamolekun's wealth of academic experience ·has no doubt sharpened my outlciok and served as a source of inspiration to me. 1 am also very grateful to Professor Dele Olowu (the Acting Head of Department) under whose intellectual guidance I developed part of the proposai which culminated ·in the final production qf .this work. My pupilage under him i though short was memorable and inspiring. He has also gone through the entire draft and his comments and criticisms, no doubt have improved the quality of the thesis. Perhaps more than anyone else, the Almighty God has used my indefatigable superviser Dr. -

A Critical Analysis of Transition to Civil Rule in Nigeria & Ghana 1960 - 2000

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF TRANSITION TO CIVIL RULE IN NIGERIA & GHANA 1960 - 2000 BY ESEW NTIM GYAKARI DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA DECEMBER, 2001 A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF TRANSITION TO CIVIL RULE IN NIGERIA & GHANA 1960 - 2000 BY ESEW NTIM GYAKARI (PH.D/FASS/06107/1993-94) BEING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PH.D) IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE, FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA. DECEMBER, 2001. DEDICATION TO ETERNAL GLORY OF GOD DECLARATION I, ESEW, NTIM GYAKARI WITH REG No PH .D/FASS/06107/93-94 DO HEREBY DECLARE THAT THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN PREPARED BY ME AND IT IS THE PRODUCT OF MY RESEARCH WORK. IT HAS NOT BEEN ACCEPTED IN ANY PREVIOUS APPLICATION FOR A DEGREE. ALL QUOTATIONS ARE INDICATED BY QUOTATION MARKS OR BY INDENTATION AND ACKNOWLEDGED BY MEANS OF REFERENCES. CERTIFICATION This dissertation entitled A Critical Analysis Of Transition To Civil Rule In Nigeria And Ghana 1960 - 2000' meets the regulation governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) Political Science of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Any serious intellectual activity such as this could hardly materialize without reference to works by numerous authors. They are duly acknowledged with gratitude in the bibliography. My heartfelt gratitude goes to my Supervisors, Dr Andrew Iwini Ohwona (Chairman) and Dr Ejembi A Unobe. -

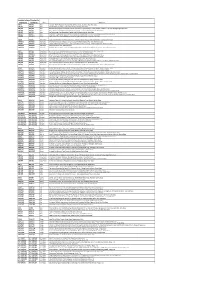

To See the Range of Serial Numbers and Centres

Candidate Serial Number Ran StartSerial EndSerial State CBTCentre ABI/1 ABI/143 Abia Freedom World Academy Int'L 12 Okpu-Umobo Street, Osisioma, Aba, Abia State. ABI/144 ABI/291 Abia Amable Nigeria Limited, 7, Old Timber Road, Umuahia, Abia State ABI/292 ABI/445 Abia National Comprehensive Secondary School, Umuokea, 1 Oji Avenue,Off 3 Glass Industry Rd Near 7-Up Plant, Obingwa Lga, Abia State ABI/446 ABI/582 Abia Mater Misericordiae Human Empowerment Computer School, 4B Obohia Rd,Aba Abia State ABI/583 ABI/730 Abia Xyz Technology, New Secretatiat, Beside Ucda Building,Umuahia, Abia State ABI/731 ABI/887 Abia Surftech Telecommunications Cbt Centre, Inside Aba North Magistrate Court, Ikot Ekpene Road, Aba, Abia State ABI/888 ABI/1045 Abia Jamb State Office, Near Ubakala Junction,Ph/Enugu Express Way,Umuahia, Abia State ADA/1 ADA/81 Adamawa Capital Government Day Secondary School, Galadima Aminu Way, Jimeta -Yola North L.G.A, Adamawa State ADA/162 ADA/252 Adamawa American University Of Nigeria, Ict Centre, 226, Modibbo Adama Way, Yola, Adamawa State ADA/82 ADA/161 Adamawa Lamido Zubairu Education Center, Opp. Center For Distance Learning, Yola Town Bye Pass, Adamawa State ADA/253 ADA/353 Adamawa Jamb State Office Yola, Adamwa State ADA/354 ADA/480 Adamawa Modibbo Adama University Of Technology, (Mautech) Cbt Hall, Along Mubi Road, Girei Lga, Yola, Adamawa State AKI/1 AKI/164 Akwa-Ibom Gestric Infortech And Management Institute (Ctr 1), No 74 Oron Road, Uyo Akwa Ibom State AKI/165 AKI/277 Akwa-Ibom Knowledge Partners Ltd, No 30, Udosen Uko Street Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKI/890 AKI/1044 Akwa-Ibom Gestric Infortech And Management Institute (Ctr 2) , No 74 Oron Road, Uyo Akwa Ibom State, AKI/637 AKI/758 Akwa-Ibom Jamb State Office, Atiku-Abubakar Road Uyo, Near State Secretariat, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

2017 Amd Stat by Inst Gender

JOINT ADMISSIONS AND MATRICULATION BOARD 2017 ADMISSION STATISTICS BY INTITUTION AND GENDER (AGE 35 & ABOVE) S/NO INSTITUTION F M TOTAL 1 A.D. RUFAI COLLEGE OF LEGAL AND ISLAMIC STUDIES ( AFF TO BAYERO UNI) KANO STATE 0 4 4 2 ABIA STATE POLYTECHNIC, ABA, ABIA STATE 0 1 1 3 ABIA STATE UNIVERSITY, UTURU, ABIA STATE 17 43 60 4 ABUBAKAR TAFAWA BALEWA UNIVERSITY, BAUCHI, BAUCHI STATE 4 11 15 5 ABUBAKAR TATARI ALI POLYTECHNIC, BAUCHI, BAUCHI STATE 2 1 3 6 ACHIEVERS UNIVERSITY OWO, ONDO STATE 2 1 3 7 ADAMAWA STATE UNIVERSITY, MUBI, ADAMAWA STATE 3 14 17 8 ADEKUNLE AJASIN UNIVERSITY, AKUNGBA-AKOKO, ONDO STATE 2 6 8 9 ADELEKE UNIVERSITY, EDE, OSUN STATE 1 1 2 10 ADENIRAN OGUNSANYA COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, IJANIKIN, LAGOS STATE 2 0 2 11 ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ONDO STATE. (AFFL TO OAU, ILE-IFE) 4 2 6 12 ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ONDO, ONDO STATE 0 2 2 13 AFRICAN THINKERS COMMUNITY OF INQUIRY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ENUGU STATE 1 0 1 14 AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY TEACHING HOSPITAL, ZARIA, KADUNA STATE 0 1 1 15 AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, KADUNA STATE 3 50 53 16 AJAYI CROWTHER UNIVERSITY, OYO, OYO STATE 0 3 3 17 AKANU IBIAM FEDERAL POLYTECHNIC, UNWANA, AFIKPO, EBONYI STATE 2 3 5 18 AKWA IBOM STATE UNIVERSITY, IKOT-AKPADEN, AKWA IBOM STATE 3 16 19 19 AKWA-IBOM STATE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, AFAHA-NSIT, AKWA IBOM STATE 6 2 8 20 AKWA-IBOM STATE POLYTECHNIC, IKOT-OSURUA, AKWA IBOM STATE 3 9 12 21 AL- HIKMAH UNIVERSITY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE 0 4 4 22 ALEX EKWUEME FEDERAL UNIVERSITY, NDUFU-ALIKE, EBONYI STATE 0 2 2 23 AL-QALAM UNIVERSITY, KATSINA, KATSINA -

Download Article

The 3rd UPI International Conference on Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Mapping Out a Strategy for Synergizing Science and Technology Institutions and Industries in Research and Skill Development in Nigeria Shehu Abdullahi Ma’aji Department of Industrial and Technology Education, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Niger State, NIGERIA [email protected] Abstract - The significance of partnership between training well as industries. Their educational systems produce large institutions of higher institutions of learning and productive sector number of scientists and technologists who find profitable (industries) is to enable Nigeria use Research and Development employment. Wealth and job creation depend on the related Science, Technology and Innovation as the fundamental application of new technology and a well trained and ingredients to enhance its competitiveness and advance itself into adaptive citizenry to keep established industries the grouping of industrialized countries by the year 2020. Thereby, promoting Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), training and competitive, as well as the development and growth of retraining, citizens will be empowered to be productive, to think, to knowledge-based industries [1] [2] be creative, to innovate and to generate wealth for Nigeria’s The African Development Bank stressed that high development. The study was a survey research in which data was collected through a 50 items questionnaire on a population of 300 economic growth rates have been achieved in countries such respondents purposively sampled from six (6) geo-political zones as Singapore, Brazil, Finland and Korea, because they have of Nigeria (18 Higher Institutions of Learning and 18 Industries). invested heavily in Research and Development (R&D) Data collected from the research questions were analysed using related to STI [3]. -

Curriculum Vitae 2019

CURRICULUM VITAE A. BIO DATA SURNAME : SABO OTHER NAMES : HASHIM BELLO DATE OF BIRTH : 3rd NOVEMBER, 1972 PLACE OF BIRTH : YALWANDASS MARITAL STATUS : MARRIED LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA : DASS STATE OF BAUCHI : BAUCHI NATIONALITY : NIGERIAN PERMANENT ADDRESS : KUYAMBANA HOUSE, YALWA VILLAGE AREA, P.O. BOX 111, DASS, BAUCHI STATE, NIGERIA. CONTACT ADDRESS : SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT, ABUBAKAR TATARI ALI POLYTECHNIC, P.M.B. 0094, BAUCHI, BAUCHI STATE. E-Mail ADDRESS : [email protected] , [email protected] MOBILE PHONE : 08058616702, 08089692957, 08180001669, & 08032926715 PLACE OF WORK : SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES, ABUBAKAR TATARI ALI POLYTECHNIC, P.M.B. 0094, BAUCHI, BAUCHI STATE. POST : PRINCIPAL LECTURER B. INSTITUTION ATTENDED WITH DATES a) Yalwa Primary School Dass, Bauchi State …….………………………………1979-1985 b) Comprehensive Day Secondary School, Azare, Bauchi State…………………..1985-1987 c) Government Science Secondary School Dass, Bauchi State……………………1987-1989 d) Government Secondary School, Bununu, Bauchi State………………………...1989-1991 e) Abubakar Tatari Ali Polytechnic, Bauchi, Bauchi State………………………..1991-1992 f) Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State…………….………………….1993-1997 g) National Teachers’ Institute, Kaduna…………………….……………………..2005-2006 h) National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos….……………………….………..2007-2010 i) Bakht al-Ruda University, Ed-Dueim, White Nile State, Republic of Sudan…..2014-2017 Page 1 of 8 CERTIFICATES OBTAINED WITH DATES 1. First School Leaving Certificate…….……………...……………………………...….1985 2. West African Examinations Council/Senior School Certificate.……………………...1991 3. Interim Joint Matriculation Board Examination Statement of Result……...…………1992 4. Bachelor of Science in Business Administration……………………...…………...….1998 5. Postgraduate Diploma in Education…………………………………………………...2006 6. Masters in Business Administration (Human Resources Management)………………2010 7. PhD in Business Administration……………………………………………...……….2017 C. PROFESSIONAL TRAINING AND WORKSHOP ATTENDED WITH DATES i. -

S/N Institution Name Female

JOINT ADMISSIONS AND MATRICULATION BOARD 2015 ADMISSION STATISTICS BY INSTITUTION AND GENDER (CANDIDATES BELOW 16) S/N INSTITUTION NAME FEMALE MALE TOTAL 1 Abdul-Gusau Polytechnic Talata-Mafara 1 2 3 2 Abia State College Of Education (Technical) 2 0 2 3 Abia State College Of Health Sciences And Management Technology Aba 8 6 14 4 Abia State Polytechnic Aba 14 14 28 5 Abia State University Uturu. 255 109 364 6 Abraham Adesanya Polytechnic Ijebu-Igbo Ogun State 14 4 18 7 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Bauchi 33 56 89 8 Abubakar Tatari Ali Polytechnic Bauchi 5 8 13 9 Achievers University Owo 38 10 48 10 Adamawa State Poly Yola 7 5 12 11 Adamawa State University Mubi 18 14 32 12 Adekunle Ajasin University Akungba-Akoko 181 105 286 13 Adeleke University Ede Osun State 58 56 114 14 Adeniran Ogunsanya College Of Education Otto/Ijanikin 45 17 62 15 Adeniran Ogunsanya College Of Education Otto/Ijanikin Lagos (Affliated To Ekit 22 11 33 16 Adeyemi College Of Education (Affliated To Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife 41 27 68 17 Adeyemi College Of Education Ondo 138 58 196 18 Afe Babalola University Ado-Ekiti 327 231 558 19 Afrihub Ict Institute Abuja 1 1 2 20 Ahmadu Bello University Zaria 275 194 469 21 Air Force Institute Of Technology Nigerian Air Force Kaduna 0 4 4 22 Ajayi Crowther University Oyo 83 56 139 23 Akanu Ibiam Federal Polytechnic Unwana Afikpo 8 8 16 24 Akperan Orshi College Of Agriculture Yandev 3 8 11 25 Akwa Ibom State University Ikot-Akpaden 75 57 132 26 Akwa-Ibom State College Of Education Afaha-Nsit 38 9 47 27 Akwa-Ibom State Polytechnic Ikot-Osurua 4 12 16 28 Al- Hikmah University Ilorin 49 20 69 29 Al-Qalam University Katsina 10 5 15 30 Alvan Ikoku College Of Educ. -

Election and Voting Pattern in Nigeria: a Study of 2015 Governorship Election in Bauchi State

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 6 Issue 11||November. 2017 || PP.52-59 Election And Voting Pattern in Nigeria: A study of 2015 governorship Election in Bauchi State Adamu Suleiman Yakubu, Abubakar Muhammad Ali School of Information and office Management Technology Abubakar Tatari Ali polytechnic, Bauchi-Nigeria. NO.16B, Badawa Layout, Nasarawa Kano-Nigeria. Corresponding Author: Adamu Suleiman Yakubu ABSTRACT: This paper examined the election and voting pattern in Nigeria with particular reference to 2015 Governorship election in Bauchi state. This study adopted quantitative means of data collection. Two research question were raised and answered in the study. The findings of theresearch empirically proved that voting pattern in Bauchi state is more greatly influenced by ethnic and kinship affiliation than party, issues and ideology. On the basis of findings of this study, it is recommended that, there is urgent need for public enlightenment by appropriate authorities on the dangers of voting based ethnic consideration. Voting a candidates is supposed be based on credibility and competence of contestant not ethnicity, religion and other parochial sentiments. KEYWORDS: Election, Voting Pattern, Nigeria, Bauchi state. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 02-11-2017 Date of acceptance: 14-11-2017 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION In life today, many things comes with a pattern. In fashion designing, designers follow a pattern, also shapes in mathematics comes with a pattern, same way with many other variables in life's endeavours. Also in voting, there is a clearly and a visible pattern that electorates follow knowingly or unknowingly in determining who to vote for and who not to vote for. -

ICAN Accredited Tertiary Institutions

THE INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF NIGERIA ICAN ACCREDITATED TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS UPDATED ON JUNE 14, 2021. Note: Students who graduated after the sessions covered in the accreditation from the Institutions highlighted in ‘RED’ will no longer enjoy exemption benefits until the accreditation is revalidated UNIVERSITIES New due Year of first Sessions covered session for re- S/N Name of Institution accreditation in accreditation Remark accreditation 1 Abia State University, Uturu 1987 2015/2016 To 2018/2019 2019/2020 2 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi State 2009 2012/2013 To 2015/2016 2016/2017 3 Achievers University , Owo, Ondo State 2010 2015/2016 To 2018/2019 2019/2020 4 Adamawa State University, Mubi Adamawa State 2008 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 5 Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State 2007 2014/2015 To 2017/2018 2018/2019 6 Adeleke University, Ede, Osun State 2017 2018/2019 To 2021/2022 2022/2023 7 Afe Babalola University ,Ado- Ekiti 2013 2016/2017 To 2019/2020 2020/2021 8 Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State 1974 2018/2019 To 2021/2022 2022/2023 9 Ajayi Crowther University,Oyo State 2009 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 10 AL-Hikman University , Ilorin, Kwara State 2009 2012/2013 To 2015/2016 Under MCATI 2016/2017 11 Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State 1994 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 12 American University Of Nigeria, Yola Adamawa State 2008 2014/2015 To 2017/2018 2018/2019 13 Babcock University, Ilishan, Ogun State 2003 2009/2010 T0 2012/2013 Under MCATI 14 Bayero University, -

(Etf) Year 2008 Reconciled Projects

EDUCATION TRUST FUND (ETF) YEAR 2008 RECONCILED PROJECTS IN EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS NATIONWIDE ETF 2008 Reconciled Projects (North-Central Zone) EDUCATION TRUST FUND YEAR 2008 RECONCILED PROJECTS AS AT 2/27/2013 11:30 North-Central Zone APPROVAL IN- NOT YET S/N STATE INSTITUTION ALLOCATION RECONCILED PROJECTS PROJECT No APPROVED COST LIMIT REMARKS PRINCIPLE DATE RECONCILED University of Jos (i) Construction of Lecture Halls and Offices for Faculty Of On-going 1 PLATEAU 119,000,000.00 Medical Science Block A at Juth Perm. Site Laminga; UNIV/JOS/ETF/07-08/01 42,666,656.39 (ii) Construcgtion of Multipurpose Laboratory for Faculty of 2007/2008 Merged Medical Science Block B at Juth Permanent Site; UNIV/JOS/ETF/07-08/02 16,780,339.52 (iii) Construction of Faculty of Environmental Science Block 48; UNIV/JOS/ETF/07-08/03 30,224,426.42 (iv) Furnishing of Classroom and Offices for Block A; UNIV/JOS/ETF/07-08/04 8,700,000.00 (v) Furnishing of Multipurpose Laboratory for Block B; UNIV/JOS/ETF/07-08/05 4,173,960.00 (vi) Procurement of One 30-Seater Coaster Bus; UNIV/JOS/ETF/07-08/06 9,550,000.00 (vii) Consultancy 6,781,309.81 (viii) Contingencies 123,307.86 119,000,000.00 Library Intervention 10,000,000.00 Academic Staff Dev. & Training Training of the following Candidates in various 50,000,000.00 disciplines (i) Barry Katu MA at Braford UK 5,110,980 On-going (ii) Ehalaiye O.O. Ph. D Victoria University of Wellington, New 8,720,500 Zealand (iii) Goselle O.