Haematopus Ostralegus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 1 General Introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds

CHAPTER 1 General introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds, sometimes referred to as waders, are birds that rely on coastal beaches, shorelines, estuaries and mudflats, or inland lakes, lagoons and the like for part of, and in some cases all of, their daily and annual requirements, i.e. food and shelter, breeding habitat. They are of the suborder Charadrii and include the curlews, snipe, plovers, sandpipers, stilts, oystercatchers and a number of other species, making up a diverse group of birds. Within Australia, shorebirds account for 10% of all bird species (Lane 1987) and in New South Wales (NSW), this figure increases marginally to 11% (Smith 1991). Of these shorebirds, 45% rely exclusively on coastal habitat (Smith 1991). The majority, however, are either migratory or vagrant species, leaving only five resident species that will permanently inhabit coastal shorelines/beaches within Australia. Australian resident shorebirds include the Beach Stone-curlew (Esacus neglectus), Hooded Plover (Charadrius rubricollis), Red- capped Plover (Charadrius ruficapillus), Australian Pied Oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris) and Sooty Oystercatcher (Haematopus fuliginosus) (Smith 1991, Priest et al. 2002). These species are generally classified as ‘beach-nesting’, nesting on sandy ocean beaches, sand spits and sand islands within estuaries. However, the Sooty Oystercatcher is an island-nesting species, using rocky shores of near- and offshore islands rather than sandy beaches. The plovers may also nest by inland salt lakes. Shorebirds around the globe have become increasingly threatened with the pressure of predation, competition, human encroachment and disturbance and global warming. Populations of birds breeding in coastal areas which also support a burgeoning human population are under the highest threat. -

Scottish Birds 22: 9-19

Scottish Birds THE JOURNAL OF THE SOC Vol 22 No 1 June 2001 Roof and ground nesting Eurasian Oystercatchers in Aberdeen The contrasting status of Ring Ouzels in 2 areas of upper Deeside The distribution of Crested Tits in Scotland during the 1990s Western Capercaillie captures in snares Amendments to the Scottish List Scottish List: species and subspecies Breeding biology of Ring Ouzels in Glen Esk Scottish Birds The Journal of the Scottish Ornithologists' Club Editor: Dr S da Prato Assisted by: Dr I Bainbridge, Professor D Jenkins, Dr M Marquiss, Dr J B Nelson, and R Swann Business Editor: The Secretary sac, 21 Regent Terrace Edinburgh EH7 5BT (tel 0131-5566042, fax 0131 5589947, email [email protected]). Scottish Birds, the official journal of the Scottish Ornithologists' Club, publishes original material relating to ornithology in Scotland. Papers and notes should be sent to The Editor, Scottish Birds, 21 Regent Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 SBT. Two issues of Scottish Birds are published each year, in June and in December. Scottish Birds is issued free to members of the Scottish Ornithologists' Club, who also receive the quarterly newsletter Scottish Bird News, the annual Scottish Bird Report and the annual Raplor round up. These are available to Institutions at a subscription rate (1997) of £36. The Scottish Ornithologists' Club was formed in 1936 to encourage all aspects of ornithology in Scotland. It has local branches which meet in Aberdeen, Ayr, the Borders, Dumfries, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Inverness, New Galloway, Orkney, St Andrews, Stirling, Stranraer and Thurso, each with its own programme of field meetings and winter lectures. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

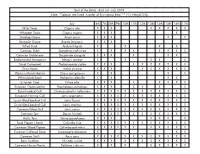

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Download Okhotsk Checklist (105 KB)

Okhotsk Checklist Okhotsk Chapter of the Wild Bird Society of Japan Home Events News Checklist Bird Guide Birding Spots Surveys References Links About Us Contact Us -- Checklist of Birds in the Okhotsk Region Exactly 354 species of wild birds have been positively recorded thus far (as of 2 April 2013) in the Okhotsk (Sub-prefectural) region of Hokkaido. This compares with 633 species (excluding 43 introduced species) for all of Japan (Ornithological Society of Japan, 2012). It is a surprisingly large number in a region that has relatively few birdwatchers. The Okhotsk region is a wonderful field blessed with a great diversity of habitats. The checklist below contains all 354 of these species, plus 4 introduced species. If you happen to be in this region and spot any birds that are not in this list, please by all means report it to us! (via the Contact Us page). One point to note in this list, however, is that while we generally have one name in Japanese for our birds, in English there is often more than one name. There is also occasionally some disagreement in the references concerning scientific names. (Avibase is a good online source to check for updates to names in current use.) For now, we have included most of the recent names that we have come across for the benefit of our readers around the world. We will continue to edit this list over time based on new information as we receive it. To download a PDF version of the checklist page, click here → Download Okhotsk Checklist (105 KB). -

The Factors Affecting Productivity and Parental

THE FACTORS AFFECTING PRODUCTIVITY AND PARENTAL BEHAVIOR OF AMERICAN OYSTERCATCHERS IN TEXAS by Amanda N. Anderson, B.S. THESIS Presented to the faculty of The University of Houston-Clear Lake in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTERS OF SCIENCE THE UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON CLEAR LAKE December, 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to give thanks and love to my parents, Lisa and Eddie for their ongoing support. You have been my rock in all circumstances and helped me persevere through life’s obstacles. I would not be the independent, hard-working, or accomplished woman I am today without you two. I want to recognize my brother, grandparents, and extended family. I have always cherished our time together during my visits back home. Thanks to my significant other, Sean Stewart for helping me get through these last few months. To my advisor, George Guillen, thank you for your guidance, support, and the opportunity to work on an amazing project. My intention for completing a research thesis was to intimately study waterbirds, and you helped me do so. I would also like to thank Jenny Oakley for providing logistical support. To my mentor and sidekick, Susan Heath, I am immensely grateful for your support, advice, and patience over the last two years. You taught me so much and helped me along the path to my avian career. I admire your passion for birds and hope I’m as bad ass as you are when I’m fifty something! I would like to thank Felipe Chavez for his ornithological expertise and always helping when called upon. -

Habitat Selection and Breeding Ecology of the Endangered Chatham Island Oystercatcher (Haematopus Chathamensis)

Habitat selection and breeding ecology of the endangered Chatham Island oystercatcher (Haematopus chathamensis) DOC RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT SERIES 206 Frances A. Schmechel and Adrian M. Paterson Published by Department of Conservation PO Box 10–420 Wellington, New Zealand DOC Research & Development Series is a published record of scientific research carried out, or advice given, by Department of Conservation staff or external contractors funded by DOC. It comprises reports and short communications that are peer-reviewed. Individual contributions to the series are first released on the departmental website in pdf form. Hardcopy is printed, bound, and distributed at regular intervals. Titles are also listed in our catalogue on the website, refer http://www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science and research. © Copyright May 2005, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1176–8886 ISBN 0–478–22683–7 This report was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing Section; editing by Helen O’Leary and layout by Lynette Clelland. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. CONTENTS Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 2. Breeding biology 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Location 8 2.3 Methods 8 2.4 Results 9 2.4.1 Clutches 9 2.4.2 Laying, incubation, and replacement intervals 10 2.4.3 Hatching, fledging, and dispersal 10 2.4.4 Success rates and causes of loss 10 2.4.5 Breeding effort and timing of the breeding season 13 2.4.6 Over-winter survival of first-year birds 13 2.5 Discussion 14 2.5.1 Laying, incubation and hatching 14 2.5.2 Re-nesting 14 2.5.3 Chick rearing, fledging, and dispersal of fledglings 14 2.5.4 Breeding success 15 2.5.5 Causes and timing of nest and chick loss 15 2.5.6 Breeding effort 16 2.5.7 Seasons and limiting factors 16 2.6 Summary 16 3. -

Site Fidelity in Oystercatchers: an Ecological Trap?

Site fidelity in Oystercatchers: An ecological trap? Jeroen Onrust Bachelor Thesis Animal Ecology Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Theunis Piersma Second reader: Prof. Dr. Joost M. Tinbergen July 2010 Table of Contents ABSTRACT 2 INTRODUCTION 3 ECOLOGICAL TRAPS 3 SITE FIDELITY 4 WHY SITE FIDELITY ? 4 BEING FAITHFUL TO YOUR MATE 5 THE DEDICATED OYSTERCATCHER 7 THE OYSTERCATCHER SOCIETY 7 ACQUIRING A TERRITORY 8 THE SPECIALIST 11 HABITAT CHANGE 12 CAUSES OF POPULATION DECLINE 12 HABITAT LOSS 14 CLIMATE CHANGE 14 DISCUSSION 16 IMPRISONED ON THE SALT MARSH 16 LOOKING TO THE FUTURE 18 REFERENCES 19 SUMMARY 22 1 Abstract The population of Oystercatchers ( Heamatopus ostralegus ) in the Netherlands declined dramatically during the last two decades as a result of deteriorating food conditions in the Dutch Wadden Sea. Oystercatchers are highly territorial and show strong site fidelity which is the tendency to return to a previously occupied location. Site fidelity may be favoured because long-term familiarity with a territory and its surroundings should lead to increased individual survival and higher fitness. To acquire a territory an Oystercatchers have to build up local dominance which forces a bird to stay at one place for many years. Consequently, this site fidelity works as an ecological trap. An ecological trap occurs when a bird chooses to stay in low quality habitat although high quality territories are available. Oystercatchers decide to stay because leaving would be detrimental as they have to build up local dominance all over again. Only if food conditions and thus habitat quality will improve, the Oystercatcher population can be saved from further decline. -

Shellfish Stocks and Fisheries

Shellfish Stocks and Fisheries Review 2014 An assessment of selected stocks The Marine Institute and Bord Iascaigh Mhara Acknowledgement: Data presented in this report originates from a variety of sources including voluntary submission of information by fishermen, through core funded projects from the Marine Institute, and through Irelands National Programme 2010-2014 which is part funded under the EU Data Collection Regulation (EC No 1543/2000) Photographs on cover by E. Fahy (Brown Crab), I. Lawlor (Surf Clam), P. Newland (Razor Clam), Man vyi (Cockles) (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cogues.jpg), S. Clarke (Native Oyster), S. Garvie (Eurasian Oystercatcher) (https://www.flickr.com/photos/rainbirder/6832039951/in/photolist- bpHZsg-f3VhdF-bz8Lsm-cDDV27-pHaHg4-oi5AtK-nUmUDa-Fpgib-FphCk-bBPYpJ-CEeJt-f49baE- CEf3p-CEguU-CEeqJ-6E74u5-7AxAxg-eW3tbb-cVh8MS-ehViZE-to9iX-7DEpMx-bkSbK9-bkSbP9- dLXA9F-oinoQp-4yQqEb-f5Ry4E-qH63C-6gpkhs-f5ByTN-cBpXVb-6gk8JV-7U7quf-6pmXnc-qH62G- cBpXZ7-odcYFr-odua5e-q3Y2XT-dT1hW5-dWqGg7-dWk4r4-dWqFg9-dWqFhG-dWk3ke-dWqFrq- dWqFud-nW1J7k-odubfv) (this image was slightly cropped to fit on cover) © Marine Institute and Bord Iascaigh Mhara 2014. Disclaimer: Although every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the material contained in this publication, complete accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Neither the Marine Institute, BIM nor the author accepts any responsibility whatsoever for loss or damage occasioned, or claimed to have been occasioned, in part or in full as a consequence of any person acting or refraining from acting, as a result of a matter contained in this publication. All or part of this publication may be reproduced without further permission, provided the source is acknowledged. -

Signals from the Wadden Sea: Population Declines Dominate Among Waterbirds Depending on Intertidal Mudflats

Ocean & Coastal Management 68 (2012) 79e88 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Ocean & Coastal Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ocecoaman Signals from the Wadden sea: Population declines dominate among waterbirds depending on intertidal mudflats Marc van Roomen a,*, Karsten Laursen b, Chris van Turnhout a, Erik van Winden a, Jan Blew c, Kai Eskildsen d, Klaus Günther e, Bernd Hälterlein d, Romke Kleefstra a, Petra Potel f, Stefan Schrader g, Gerold Luerssen h, Bruno J. Ens a a SOVON Dutch Centre For Field Ornithology, P.O. Box 6521, 6503 GA Nijmegen, The Netherlands b Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Grenaavej 12, DK-8410 Roende, Denmark c BioConsult SH, Brinckmannstr. 31, 25813 Husum, Germany d Nationalparkverwaltung Schleswig-Holsteinisches Wattenmeer, Schlossgarten 1, D-25832 Tönning, Germany e Schutzstation Wattenmeer, Nationalpark-Haus, Hafenstrasse 3, D-25813 Husum, Germany f Nationalparkverwaltung Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer, Virchowstrasse 1, D-26382 Wilhelmshaven, Germany g Landesbetrieb für Küstenschutz, Nationalpark und Meeresschutz Schleswig-Holstein, Herzog-Adolf Strasse 1, D-25813 Husum, Germany h Common Wadden Sea Secretariat, Virchowstrasse 1, D-26382 Wilhemshaven, Germany article info abstract Article history: The Wadden Sea, shared by Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands, is one of the world’s largest Available online 12 April 2012 intertidal wetlands. Waterbirds are an important element of the Wadden Sea ecosystem. By their migratory behaviour they connect the Wadden Sea with other sites, ranging from the arctic to the western seaboards of Europe and Africa, forming the East-Atlantic Flyway. The Joint Monitoring of Migratory Birds (JMMB) project of the Trilateral Monitoring and Assessment Program (TMAP) follows the changes in population size within the Wadden Sea. -

Pied Oystercatcher Haematopus Longirostris Review of Current Information in NSW May 2008

NSW SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Pied Oystercatcher Haematopus longirostris Review of Current Information in NSW May 2008 Current status: The Pied Oystercatcher Haematopus longirostris is currently listed as Rare in South Australia under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 (NPW Act), but is not listed under Commonwealth legislation. The NSW Scientific Committee recently determined that the Pied Oystercatcher meets criteria for listing as Endangered in NSW under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (TSC Act), based on information contained in this report and other information available for the species. Species description: The Pied Oystercatcher is a medium-sized (45 cm), sturdy, strikingly black and white shorebird with a long orange-red bill, red eyes and stout red-pink legs. It has distinctive loud, piping calls. A similar species, the Sooty Oystercatcher Haematopus fuliginosus, has the same red bill, eyes and legs but is wholly black. Taxonomy: Haematopus longirostris Vieillot 1817, is monotypic (i.e. no subspecies) and an Australasian endemic species in a cosmopolitan genus. Distribution and number of populations: In NSW the Pied Oystercatcher occupies beaches and inlets along the entire coast, the northern and southern populations having possible interchange with the Queensland and Victorian populations, respectively. It occurs and breeds around the Australian and Tasmanian coastlines, but has declined throughout much of its range and is of conservation concern in south-eastern Australia because it is vulnerable to habitat destruction -

Hybridisation by South Island Pied Oystercatcher (Haematopus Finschi) and Variable Oystercatcher (H

27 Notornis, 2010, Vol. 57: 27-32 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. Hybridisation by South Island pied oystercatcher (Haematopus finschi) and variable oystercatcher (H. unicolor) in Canterbury TONY CROCKER* 79 Landing Drive, Pyes Pa, Tauranga 3112, New Zealand SHEILA PETCH 90a Balrudry Street, Christchurch 8042, New Zealand PAUL SAGAR National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 8602, Christchurch 8011, New Zealand Abstract We document hybridisation between South I pied oystercatcher (Haematopus finschi) and variable oystercatcher (H. unicolor) in Canterbury from 1989 to 2005. From 2 observations of hybridisation between South I pied oystercatcher x variable oystercatcher when first discovered, the hybrid swarm has increased to around 17 pairs, including South I pied oystercatcher pairs, variable oystercatcher pairs, hybrid pairs, and mixed pairs. We present data on the birds and their offspring and speculate on possible causes and implications of hybridisation for conservation of the taxa. Crocker, T.; Petch, S.; Sagar, P. 2010. Hybridisation by South Island pied oystercatcher (Haematopus finschi) and variable oystercatcher (H. unicolor) in Canterbury. Notornis 57(1): 27-32. Keywords South Island pied oystercatcher; Haematopus finschi; variable oystercatcher; Haematopus unicolor; hybridisation; conservation management INTRODUCTION species. Hybridisation between these 2 species South I pied oystercatchers (Haematopus finschi) of oystercatchers has not been documented in (hereafter SIPO) and variable oystercatchers (H. detail previously. Here, we outline the discovery unicolor) (hereafter VOC) are taxa of uncertain and monitoring of an initial 2 hybridising pairs of affinities endemic to New Zealand’s main islands SIPO/VOC, leading to the establishment of a small (Banks & Paterson 2007).