PDF (Mobile-Friendly)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAKING CODE ZERO Part 2

October 2018 Issue 23 PLUS MAKING CODE ZERO part 2 Includes material PLAY BLACKPOOL not in the video Report from the show! event... CONTENTS 32. RECREATED SPECTRUM Is it any good? 24. MIND YOUR LANGUAGE 18. Play Blackpool 2018 Micro-Prolog. The recent retro event. FEATURES GAME REVIEWS 4 News from 1987 DNA Warrior 6 Find out what was happening back in 1987. Bobby Carrot 7 14 Making Code Zero Devils of the Deep 8 Full development diary part 2. Spawn of Evil 9 18 Play Blackpool Report from the recent show. Hibernated 1 10 24 Mind Your Language Time Scanner 12 More programming languages. Maziacs 20 32 Recreated ZX Spectrum Bluetooth keyboard tested. Gift of the Gods 22 36 Grumpy Ogre Ah Diddums 30 Retro adventuring. Snake Escape 31 38 My Life In Adventures A personal story. Bionic Ninja 32 42 16/48 Magazine And more... Series looking at this tape based mag. And more…. Page 2 www.thespectrumshow.co.uk EDITORIAL Welcome to issue 23 and thank you for taking the time to download and read it. Those following my exploits with blown up Spectrums will be pleased to I’ll publish the ones I can, and provide hear they are now back with me answers where fit. Let’s try to get thanks to the great service from Mu- enough just for one issue at least, that tant Caterpillar Games. (see P29) means about five. There is your chal- Those who saw the review of the TZX All machines are now back in their lenge. Duino in episode 76, and my subse- cases and working fine ready for some quent tweet will know I found that this The old school magazines had many filming for the next few episodes. -

The Adventurers Club Ltd. 64C Menelik Road, London NW2 3RH

The Adventurers Club Ltd. 64c Menelik Road, london NW2 3RH. Telephone: 01-794 1261 MEMBER'S DOSSIERS Nos 33 & 34 - SUMMER 1988 ******************************************* REVIEWS: LEGEND OF THE SWORD MINDFIGHTER RETURN TO DOOM CORRUPT I ON VIRUS THE BERMUDA PROJECT KARYSSIA FEDERATION APACHE GOLD RONNIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD CRYSTAL OF CARUS S.T.I. NOVA ARTICLES BY: RICHARD BARTLE TONY BRIDGE KEITH CAMPBELL HUGH WALKER ------LATEST ----NEWS --ON ---THE ADVENTURING SCENE BASIC ADVENTURING DISCOUNTED SOFTWARE -----------AND MUCH MORE!II BelD-Llaa Details •••e ...........*. EDITORIAL **.*.***. Members have access to our extensive databank of blnts an4 solutions for most of the popular adventure games. Be1p can be obtained as Dear Fellow Adventurer, follows: Welcome to MDs Nos 33-34! • By Mail. Please enclose a Btamped Addressed Bnvelope. Give us the title and What a summer! As explained in our "Summer 1988 - Newsflash", the version of the g&llle(s), and detail the queryUes) wbich you have. We publication of this Dossier was delayed because of two postal strikes shall usually reply to you on the day of receipt of your letter. (one local unofficial and one national official) which affected our Overseas Members using the Mail Belp-Line should enclose an I.R.C. for receiving articles and reviews which were scheduled for publication in a speedy reply, otherwise the answers to their queries will be sent this issue. True, we could have filled the Dossier with 8 additional together with their next Member's Dossier. pages of reviews of old adventures of no interest to anyone but, rightly or wrongly, we thought that maintaining our high standards • By 'lelephone: was more important than publishing just for the sake of doing so. -

(100% Working) Notes

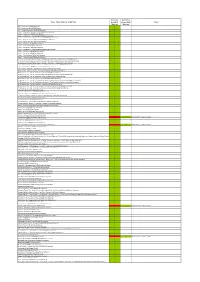

FF v0.9.24a Fixed Weak Name - TOSEC Collection of 803 Titles Beta (97% Sectors (100% Notes Working) Working) 007 - Licence to Kill (1989)(Domark) Y 007 - Live and Let Die (1988)(Domark) Y 007 - The Spy Who Loved Me (1990)(Domark) Y 2 por 1 - Arkanoid II - Revenge of Doh (1989)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - Chase H.Q. (1989)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - Cybernoid II - The Revenge (1988)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - Mask III - Venom Strikes Back (1989)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - Mickey Mouse (1988)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - North Star (1989)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - Platoon (1989)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - Renegade (1988)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - Renegade II - Target Renegade (1988)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - Techno-Cop (1988)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - The Deep (1989)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - The Muncher (1989)(Erbe Software) Y 2 por 1 - Thunder Blade (1988)(Erbe Software) Y 20 Game Pack - NED + Missile Defence + Billy Bong + Seiddab Attack + Star Warrior (19xx)(Comet) Y 20 Game Pack - Pi-R-Squared + Pyramania + Strontiumdog + Meteor Storm + Overlords (19xx)(Comet) Y 20 Game Pack - Showjumping + Xeno + Snooker + Nifty Lifty + Tutenkahmun (19xx)(Comet) Y 20 Game Pack - SOS + Mushroom Mania + 3D Knot + Project Future + 1994 (19xx)(Comet) Y 4 Soccer Simulators (1989)(Codemasters Gold)(2 Side Version) Y 4 Top Games - Catch 23 + Nemesis the Warlock (1987)(Martech Games) Y 4 Top Games - Pulsator + Slaine - The Celtic Barbarian (1987)(Martech Games) Y 40 Principales, Los - Vol. -

Home Computing Weekly Magazine Issue

WIN Computers or 200 prizes of Somes Outback a new ayers? game from Paramount ;; games playing machine* This is the so must be won conclusion in a report b people about their km Software of, and altitude* to. computers. reviews for: It predicts thai an oil Spectrum, BBC Dragon, SordMS and Texas Ttic studj was drawn u| Market, ng Direction, conjunction with Gall . Graham Tillotson. managing ' director of Market' ' Direction, said: "We ! found lime and imu- .n],nn Black box hits pirates Three fun li forthespect. t PLUS: .alt piracy. 1 Microdcal, the Cornwall-based programs to type PWaTEHDVEWW" inforthe Commodore 6d, Oric and Dragon Symes said the bos.. COM unmarked chip-, rlnjiit AND Ihc Dragon's jowick po dc encrypted the game. U.S. Scene, your letters, software charts for six computers... days on it anil then told •Forger it.'" Mr Symes said Nan h era Software Consultants hid been working on the key I August and the design cost into five figures. Microdcfll's games us cost about 18, but [iuuard will be priced ar £9.95. 1 then, said Mr Symes, Microdcal was losing money compared wilh ils other products. He said: '"The industry » die wiihoui something like th Only the other day we had Continued on page 6 April 17-Aprll 23, 19B4 MO. 58 REGULARS Type in our Easier Special for (he BBC micro and fun. II s Classified ads start on . SOFTWARE REVIEWS PROGRAMS HOME COMPUTING (effects for your own WKRT ir memory in this wrtl game? bHlflTB EOTSI HOME COMPUTING WEEKLY 11 CAN YOU HANDLE THE ULTIMATE? FEATURE PACKED. -

Level9-Catalog3

Level 9 Adventures Ingrid's Back! Gnome Ranger Knight Ore Jewels of l)arkness Scapeghost Lancelot Time&Magik Silicon Dreams cassette/disc. £19.95 £19.95 £ 19.9 5 £ 14.95 £19.95 £19.95 £19.95 £19.95 d Amiga £ 14.95 £14.95 £14.95 £9.95 £14.95 £ 14.95 £ 14.95 c Amstrad CPC £19.95 £ 19 .9 5 £19.95 £ 14.95 £19.95 d CPC/PCW/+3 £ 14.95 £ 14 .95 £14.9 5 £9.95 £14.95 d Apple II £ 14.95 £ 14 .9 5 £14.95 £ 9 .95 £ 14.95 £ 14.95 £14.95 c Atari XL/XE £ 14.95 £ 14.95 £14.9 5 £ 9 .95 £ 14.95 £ 14.95 £14.95 d Atari XL/XE £ 19.95 £ 19.95 £19.9 5 £ 14.95 £ 19.95 £19.95 £ 19 .9 5 £19.95 d Atari ST £ 14.95 £ 14 .95 £ 14 .9 5 £ 9 .95 £ 14.95 £ 14.9 5 d BBC 48K+/Mstr £ 14.95 £14.95 £ 14.95 £9.95 £14.95 £14.95 c Commodore 64 £ 14.9 5 £ 14 .95 £ 14.95 £ 9.95 £14.95 £ 14.95 d Commodore 64 £ 19.95 £ 19.95 £ 19.95 £ 14.95 £19.95 d IBM/Arnst PC £19.95 £19.95 £14.95 £19.95 £19.95 d Macintosh £14.95 £14.95 £9.95 £14.95 £14.95 c MSX £ 14.95 £14.95 £14.95 £9.95 £14.95 c Spectrum Underlined prices mean games with pictures: Scapeghost, Ingrid's Back!, Lancelot hand-drawn; Knight Ore, Gnome Ranger, Time and Magik digitised; others cartoon-style. -

The Adventurers Club Ltd. 64C Menelik Road, London NW2 3RH

The Adventurers Club Ltd. 64c Menelik Road, London NW2 3RH. Telephone: 01-794 1261 MEMBER'S DOSSIERS Nos 35 & 36 - NOVEMBER 1988/DECEMBER 1988 *********************************************************** REVIEWS: INGRID'S BACK! SHADOWGATE SCOTT ADAM'S SCOOPS THE INHERITANCE POLICE QUEST BARD' S TALE II CLOUD 99 BUGSY HAUNTED HOUSE THE ALIEN FROM OUTER SPACE DR JEKYLL AND MR HYDE ARTICLES BY: RICHARD BARTLE TONY BRIDGE KEITH CAMPBELL MIKE GERRARD HUGH WALKER LATEST NEWS ON THE ADVENTURING SCENE BASIC ADVENTURING DISCOUNTED SOFTWARE AND MUCH MORE!!! 12 Help-Line Details #3 ***************** EDITORIAL ********* Members have access to our extensive databank of hints and solutions Dear Fellow Adventurer, for most of the popular adventure games. Help can be obtained as follows: Welcome to MDs Nos 35-36, our Christmas issue! * By Mail: We have been very active during the past few weeks, and the most Please enclose a Stamped Addressed Envelope. Give us the title and important item of news this month is the announcement of the version of the game(s), and detail the query(ies) which you have. We "Golden Chalice Awards Presentation Ceremony". Please refer to the shall usually reply to you on the day of receipt of your letter. enclosed leaflet for full details about this important occasion, and Overseas Members using the Mail Help-Line should enclose an I.R.C. for do make sure you that you pencil 25.02.89 in your diary! a speedy reply, otherwise the answers to their queries will be sent Owing to popular demand, we have now produced specially-designed together with their next Member's Dossier. -

Nintendo Famicom Indiana Jones

RG16 Cover UK.qxd:RG16 Cover UK.qxd 20/9/06 13:06 Page 1 retro gamer COMMODORE • SEGA • NINTENDO • ATARI • SINCLAIR • ARCADE * VOLUME TWO ISSUE FOUR Nintendo Famicom Is this the best console of all time? Indiana Jones Opening the gaming ark Rare’s GoldenEye 007 heaven on the N64 Pong Wars A brief history of videogames Retro Gamer 16 £5.99 UK $14.95 AUS V2 $27.70 NZ 04 Untitled-1 1 1/9/06 12:55:47 RG16 Intro/Contents.qxd:RG16 Intro/Contents.qxd 20/9/06 14:27 Page 3 <EDITORIAL> Editor = Martyn Carroll ([email protected]) Deputy Editor = Aaron Birch ([email protected]) Art Editor = Craig Chubb Sub Editors = Rachel White + James Clark Contributors = Alicia Ashby + Simon Brew Richard Burton + Jonti Davies Ashley Day + Paul Drury Frank Gasking + Geson Hatchett Craig Lewis + Robert Mellor Per Arne Sandvik + Spanner Spencer John Szczepaniak+Chris Wild <PUBLISHING & ADVERTISING> Operations Manager = Glen Urquhart Group Sales Manager = Linda Henry Advertising Sales = Danny Bowler Accounts Manager = Karen Battrick repare for invasion, should be commended leading up to the event. CGE 2005 Circulation Manager = as retro fans, (knighted?) for his efforts in is on course to surpass last year’s Steve Hobbs helloexhibitors and getting the show on the road. successful debut in every way, Marketing Manager = Iain "Chopper" Anderson celebrities descend The failure of Game Zone Live and it’s hoped that one day the Editorial Director = P on London for the goes to show that even a large show will be as big as its US Wayne Williams second Classic Gaming Expo. -

Interplay of Thematic and Ludological Elements in Western-Themed Games

This is an electronic reprint of the original article. This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail. Junnila, Miikka; Reunanen, Markku; Heikkinen, Tero The Interplay of Thematic and Ludological Elements in Western-Themed Games Published in: Kinephanos Published: 29/05/2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published under the following license: CC BY-NC-ND Please cite the original version: Junnila, M., Reunanen, M., & Heikkinen, T. (2019). The Interplay of Thematic and Ludological Elements in Western-Themed Games. Kinephanos, (special issue May 2019), 40-73. https://www.kinephanos.ca/2019/the- interplay-of-thematic-and-ludological-elements-in-western-themed-games/ This material is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, and duplication or sale of all or part of any of the repository collections is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for your research use or educational purposes in electronic or print form. You must obtain permission for any other use. Electronic or print copies may not be offered, whether for sale or otherwise to anyone who is not an authorised user. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Special Issue The Rise(s) and Fall(s) of Video Game Genres May 2019 40-73 The Interplay of Thematic and Ludological Elements in Western-Themed Games Miikka Junnila, Markku Reunanen & Tero Heikkinen Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture, University of Turku, University of the Arts Helsinki Abstract: The Wild West has been productized and remediated a number of times over the last hundred of years – and even earlier than that. -

S Q X W W X А V А

RETRO7 Cover UK 09/08/2004 12:20 PM Page 1 ❙❋❙P✄❍❇N❋❙ ❉PNNP❊P❙❋•❚❋❍❇•❖❏❖❋❖❊P•❇❇❙❏•❚❏❖❉M❇❏❙•❇❉P❙❖•& NP❙❋ * ❏❚❚❋✄❚❋❋❖ * ❙❋❙P✄❍❇N❋❙ £5.99 UK • $13.95 Aus $27.70 NZ ISSUE SEVEN I❋✄❇❇❙❏✄❚✄G❇N❏M ◗P❋❙✄❏IP✄I❋✄◗❙❏❉❋? ❉M❇❚❚❏❉✄❍❇N❏❖❍✄❋◗P✄L I❋✄❚IP✄& ❏❚✄❚❇❙✎✄N❇I❋✄❚N❏I ❉P❏❖✏P◗✄❉P❖❋❙❚❏P❖❚ I❏❉I✄IPN❋✄❋❙❚❏P❖✄❇❚✄❈❋❚? ◗M❚✄MP❇❊❚✄NP❙❋✢ I❋✄M❋❋M✄ ❚P❙✄❉P❖❏❖❋❊✎✄ L❋❏I✄❉❇N◗❈❋MM9✎ ❚✄❊❋❚❋❙✄❏❚M❇❖❊✄❊❏❚❉❚ >SYNTAX ERROR! >MISSING COVERDISC? <CONSULT NEWSAGENT> & ❇❙❉❇❊❋✄I❖✄◗❊❇❋ 007 Untitled-1 1 1/9/06 12:55:47 RETRO7 Intro/Hello 11/08/2004 9:36 PM Page 3 hello <EDITORIAL> >10 PRINT "hello" Editor = >20 GOTO 10 Martyn Carroll >RUN ([email protected]) Staff Writer = Shaun Bebbington ([email protected]) Art Editor = Mat Mabe Additonal Design = Roy Birch + Da Beast + Craig Chubb Sub Editors = Rachel White + Katie Hallam Contributors = Richard Burton + David Crookes Jason Darby + Richard Davey Paul Drury + Ant Cooke Andrew Fisher + Richard Hewison Alan Martin + Robert Mellor Craig Vaughan + Iain "Plonker" Warde <PUBLISHING & ADVERTISING> Operations Manager = Debbie Whitham Group Sales & Marketing Manager = Tony Allen hello Advertising Sales = Linda Henry elcome to another horseshit”, there must be a others that we are keeping up Accounts Manager = installment in the Retro thousand Retro Gamer readers our sleeves for now. We’ve also Karen Battrick WGamer saga. I’d like to who disagree. Outnumbered and managed to secure some quality Circulation Manager = Steve Hobbs start by saying a big hello to all outgunned, my friend. coverdisc content, so there’s Marketing Manager = of those who attended the Classic Anyway, back to the show. -

The Inform Designer's Manual

Cited Works of Interactive Fiction The following bibliography includes only those works cited in the text of this book: it makes no claim to completeness or even balance. An index entry is followed by designer's name, publisher or organisation (if any) and date of first substantial version. The following denote formats: ZM for Z-Machine, L9 for Level 9's A-code, AGT for the Adventure Game Toolkit run-time, TADS for TADS run-time and SA for Scott Adams's format. Games in each of these formats can be played on most modern computers. Scott Adams, ``Quill''-written and Cambridge University games can all be mechanically translated to Inform and then recompiled as ZM. The symbol marks that the game can be downloaded from ftp.gmd.de, though for early games} sometimes only in source code format. Sa1 and Sa2 indicate that a playable demonstration can be found on Infocom's first or second sampler game, each of which is . Most Infocom games are widely available in remarkably inexpensive packages} marketed by Activision. The `Zork' trilogy has often been freely downloadable from Activision web sites to promote the ``Infocom'' brand, as has `Zork: The Undiscovered Underground'. `Abenteuer', 264. German translation of `Advent' by Toni Arnold (1998). ZM } `Acheton', 3, 113 ex8, 348, 353, 399. David Seal, Jonathan Thackray with Jonathan Partington, Cambridge University and later Acornsoft, Topologika (1978--9). `Advent', 2, 47, 48, 62, 75, 86, 95, 99, 102, 105, 113 ex8, 114, 121, 124, 126, 142, 146, 147, 151, 159, 159, 179, 220, 221, 243, 264, 312 ex125, 344, 370, 377, 385, 386, 390, 393, 394, 396, 398, 403, 404, 509 an125. -

Commodore Amiga

Commodore Amiga Last Updated on September 27, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 007: Licence to Kill Domark 3D World Soccer Simulmondo 3D World Tennis Simulmondo 4-Get-It TTR Development 4D Sports Boxing Mindscape 4D Sports Driving Mindscape Accordion UnSane Creations Action Cat 1001 Software Action Fighter Firebird Action Sixteen Digital Integration Adrenalynn Exponentia ADS: Advanced Destroyer Simulator Futura - U.S. Gold Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Eye of the Beholder SSI Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Eye of the Beholder II - The Legend of Darkmoon SSI Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Heroes of the Lance SSI Advantage Tennis Infogrames Adventure Construction Set Electronic Arts Adventures in Math Free Spirit Adventures of Maddog Williams in The Dungeons of Duridian, The Game Crafters Adventures of Robin Hood, The Millennium After the War Dinamic Airborne Ranger MicroProse Alien Breed II: The Horror Continues Team 17 Alien Breed: Special Edition 92 Team 17 Alien Breed: Tower Assault Team 17 Alien Legion Gainstar Software Alien Syndrome ACE All Dogs Go to Heaven Merit All New World of Lemmings Psygnosis Alpha Waves Infogrames Altered Beast Activision Altered Destiny Accolade Amberstar Thalion Amegas Pandora American Tag-Team Wrestling Zeppelin Platinum Amiga Karate Eidersoft Amy's Fun-2-3 Adventure Devasoft Anarchy Psyclapse Ancient Games Energize Another World Delphine - U.S. Gold Antago Art of Dreams Antheads: It Came from the Desert II Cinemaware Apache Team 17 Apidya Play Byte Apocalypse Virgin Apprentice Rainbow Arts Aquatic Games, The: Starring James Pond and the Aquabats Millennium Arabian Nights Krisalis Arachnophobia Disney - Titus Arazok's Tomb Aegis Arcade Fruit Machine Zeppelin Platinum Arcade Pool Team 17 Archer MacLean's Pool Virgin Archipelagos Logotron This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Al-Strad Blizzard Pass the Castle Castle Blackstar Castle Eerie

ADVENTURE PROBE INDEX HINTS AND TIPS VOL ISSUE VOL [ISSUE VOL [ISSUE vOL ISSUE VOL ISSUE Adventureland Vol 2 7 Adventure Quest Vol + 8 Vol 1 t@ Aftershock Vol + 7 Vol 1 10 Al-Strad Vol 1 2 American Suds 3 Vol 2 7 Apache Gold Vol 2 5 Vol 2 7 Bal lyhoo Vol 1 16 Vol 2 12 Bards Tale | Vol 2 11 Bards Tale 1! Val 2 12 Beyond Zork Vol 2 12 Bermuda Project Vol 2 12 The Big Sleeze Vol 1 15 Vol 1 16 Blizzard Pass Vol 2 7 Vol 2 8 Vol 2 10 Boggilt Vol + 5 Vol 1 6 Vol t 8 Book of the Dead Vol 2 1 Vol 2 2 Vol 2 5 Bored of the Rings Vol 1 1 Vol 1 2 Vol 1 3 Vol 1} 6 Borrowed Time Vol t+ 8 Vol 2 7 Brawn Free Vol 1 2 Breakers Vol 2 7 Buckeroo Banzai Vol t 17 Bugsey Ptl Vol + 9 Bulbo/Lizard King Vol 1 17 Bureaucracy Vol 2 12 The Castle Vol 1 19 Castle Blackstar Vol 1 8 Vol 1 11 Castle Eerie Vol 1 18 The Challenge Vol 1 19 Chaos Factor Vol 1 4 Circus Vol 1 3 Vol 2 6 Colossal Cave Volt 1+ 3 Colour of Magic Vol 1 8 Vol { 10 Corruption Vol 2 12 Cracks of Fire Vol 2 2 Crown of Ramhotep Vol 2 5 Crystal Cavern Vol 2 7 Crystal of Chantie Vol 2 6 Cuddles Vol 2 2 Curses/Crawley Manor Vol 1 10 Curse of Shaleth Vol 1 18 Davy Jones Locker Vol 2 9 Dark Crystal Vol 2 2 Desperado Vel 1 8 Desert Island Vol 2 11 Devil's island Vol 2 11 Diamond Trail Vol 1+ 3 Domes of Sha , Vol 2 12 Dodgy Geezers Vol 1 12 Dragonscrypt Vol 2 5 Dragonworid Vol t+ 3 Dungeon Adventure Vol 1 9 Dusk over Elfinton Vol 2 11 Earthshock Vol 1 16 El Dorado Vol! 1 16 Emerald isle Vol 1 {i Vol ft 2 Vol t 8 Empire of Karn Vol 1 3 Enchanted Cottage Vol 2 10 Enchanter Vol § 12 Vol ¢ 13 Vol { 14 Vol 2 7: Vol 2 12 Enthar 7 Vol t+ 6 the Vol Vol Vol 2 © Erik Viking ee Escape from Tramm Vol 1 Q Eureka Vol Vo! Vel + 7 Vol om Excalibur Vol oe Vo! Fahrenheit 451 Vol 1 6 Fausts Folly Vol 1 9 Feasibility Exper.