White Mountain Silverling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Common Native Plants the Diversity of Acadia National Park Is Refl Ected in Its Plant Life; More Than 1,100 Plant Species Are Found Here

National Park Service Acadia U.S. Department of the Interior Acadia National Park Checklist of Common Native Plants The diversity of Acadia National Park is refl ected in its plant life; more than 1,100 plant species are found here. This checklist groups the park’s most common plants into the communities where they are typically found. The plant’s growth form is indicated by “t” for trees and “s” for shrubs. To identify unfamiliar plants, consult a fi eld guide or visit the Wild Gardens of Acadia at Sieur de Monts Spring, where more than 400 plants are labeled and displayed in their habitats. All plants within Acadia National Park are protected. Please help protect the park’s fragile beauty by leaving plants in the condition that you fi nd them. Deciduous Woods ash, white t Fraxinus americana maple, mountain t Acer spicatum aspen, big-toothed t Populus grandidentata maple, red t Acer rubrum aspen, trembling t Populus tremuloides maple, striped t Acer pensylvanicum aster, large-leaved Aster macrophyllus maple, sugar t Acer saccharum beech, American t Fagus grandifolia mayfl ower, Canada Maianthemum canadense birch, paper t Betula papyrifera oak, red t Quercus rubra birch, yellow t Betula alleghaniesis pine, white t Pinus strobus blueberry, low sweet s Vaccinium angustifolium pyrola, round-leaved Pyrola americana bunchberry Cornus canadensis sarsaparilla, wild Aralia nudicaulis bush-honeysuckle s Diervilla lonicera saxifrage, early Saxifraga virginiensis cherry, pin t Prunus pensylvanica shadbush or serviceberry s,t Amelanchier spp. cherry, choke t Prunus virginiana Solomon’s seal, false Maianthemum racemosum elder, red-berried or s Sambucus racemosa ssp. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Dry River Wilderness

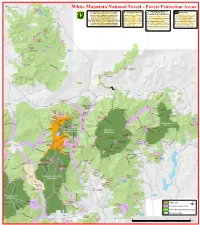

«¬110 SOUTH White Mountain National Forest - Forest Protection Areas POND !5 !B Forest Protection Areas (FPAs) are geographic South !9 Designated Sites !9 The Alpine Zone Wilderness Pond areas where certain activities are restricted to A Rarity in the Northeast Rocky prevent overuse or damage to National Forest Designated sites are campsites or Wilderness Areas are primitive areas Pond resources. Restrictions may include limits on picnic areas within a Forest The alpine zone is a high elevation area in with few signs or other developments. !B camping, use of wood or charcoal fires and Protection area where otherwise which trees are naturally absent or stunted Trails may be rough and difficult to maximum group size. FPAs surround certain features prohibited activities (camping at less that eight feet tall. About 8 square follow. Camping and fires are gererally miles of this habitat exists in the prohibited within 200 feet of any trail W (trails, ponds, parking areas, etc) with either a 200-foot and/or fires) may occur. These e s or ¼ mile buffer. They are marked with signs sites are identified by an official Northeast with most of it over 4000 feet unless at a designated site. No more t M as you enter and exit so keep your eyes peeled. sign, symbol or map. in elevation. Camping is prohibited in the than ten people may occupy a single i la TYPE Name GRID n alpine zone unless there is two or more campsite or hike in the same party. Campgrounds Basin H5 feet of snow. Fires are prohibited at all Big Rock E7 !B Blackberry Crossing G8 ROGERS times. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

Recovery Plan for Liatris Helleri Heller’S Blazing Star

Recovery Plan for Liatris helleri Heller’s Blazing Star U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia RECOVERY PLAN for Liatris helleri (Heller’s Blazing Star) Original Approved: May 1, 1989 Original Prepared by: Nora Murdock and Robert D. Sutter FIRST REVISION Prepared by Nora Murdock Asheville Field Office U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Asheville, North Carolina for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Approved: Regional Director, U S Fish’and Wildlife Service Date:______ Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover andlor protect listed species. Plans published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) are sometimes prepared with the assistance ofrecovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and other affected and interested parties. Plans are reviewed by the public and submitted to additional peer review before they are adopted by the Service. Objectives of the plan will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not obligate other parties to undertake specific tasks and may not represent the views or the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in developing the plan, other than the Service. Recovery plans represent the official position ofthe Service only after they have been signed by the Director or Regional Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. By approving this recovery plan, the Regional Director certifies that the data used in its development represent the best scientific and commercial information available at the time it was written. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012 Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012 Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM LIST OF THE RARE PLANTS OF NORTH CAROLINA 2012 Edition Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist and John Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org Table of Contents LIST FORMAT ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 NORTH CAROLINA RARE PLANT LIST ......................................................................................................................... 10 NORTH CAROLINA PLANT WATCH LIST ..................................................................................................................... 71 Watch Category -

Maine's Endangered and Threatened Plants

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Maine Collection 1990 Maine's Endangered and Threatened Plants Maine State Planning Office Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Forest Biology Commons, Forest Management Commons, Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons, Plant Biology Commons, and the Weed Science Commons Recommended Citation Maine State Planning Office, "Maine's Endangered and Threatened Plants" (1990). Maine Collection. 49. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Collection by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BACKGROUND and PURPOSE In an effort to encourage the protection of native Maine plants that are naturally reduced or low in number, the State Planning Office has compiled a list of endangered and threatened plants. Of Maine's approximately 1500 native vascular plant species, 155, or about 10%, are included on the Official List of Maine's Plants that are Endangered or Threatened. Of the species on the list, three are also listed at the federal level. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. has des·ignated the Furbish's Lousewort (Pedicularis furbishiae) and Small Whorled Pogonia (lsotria medeoloides) as Endangered species and the Prairie White-fringed Orchid (Platanthera leucophaea) as Threatened. Listing rare plants of a particular state or region is a process rather than an isolated and finite event. -

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region for Toll-Free Reservations 1-888-237-8642 Vol

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region For Toll-Free reservaTions 1-888-237-8642 Vol. 19 No. 1 GPS: 893 White Mountain Hwy, Tamworth, NH 03886 PO Box 484, Chocorua, NH 03817 email: [email protected] Tel. 1-888-BEST NHCampground (1-888-237-8642) or 603-323-8536 www.ChocoruaCamping.com www.WhiteMountainsLodging.com We Trust That You’ll Our Awesome Park! Escape the noisy rush of the city. Pack up and leave home on a get-away adventure! Come join the vacation tradition of our spacious, forested Chocorua Camping Village KOA! Miles of nature trails, a lake-size pond and river to explore by kayak. We offer activities all week with Theme Weekends to keep the kids and family entertained. Come by tent, pop-up, RV, or glamp-it-up in new Tipis, off-the-grid cabins or enjoy easing into full-amenity lodges. #BringTheDog #Adulting Young Couples... RVers Rave about their Families who Camp Together - Experience at CCV Stay Together, even when apart ...often attest to the rustic, lakeside cabins of You have undoubtedly worked long and hard to earn Why is it that both parents and children look forward Wabanaki Lodge as being the Sangri-La of the White ownership of the RV you now enjoy. We at Chocorua with such excitement and enthusiasm to their frequent Mountains where they can enjoy a simple cabin along Camping Village-KOA appreciate and respect that fact; weekends and camping vacations at Chocorua Camping the shore of Moores Pond, nestled in the privacy of a we would love to reward your achievement with the Village—KOA? woodland pine grove. -

An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa

Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS Volume 98 Number Article 4 1991 An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa Dean M. Roosa Department of Natural Resources Lawrence J. Eilers University of Northern Iowa Scott Zager University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright © Copyright 1991 by the Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias Part of the Anthropology Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Roosa, Dean M.; Eilers, Lawrence J.; and Zager, Scott (1991) "An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa," Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS, 98(1), 14-30. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias/vol98/iss1/4 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jour. Iowa Acad. Sci. 98(1): 14-30, 1991 An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa DEAN M. ROOSA 1, LAWRENCE J. EILERS2 and SCOTI ZAGER2 1Department of Natural Resources, Wallace State Office Building, Des Moines, Iowa 50319 2Department of Biology, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, Iowa 50604 The known vascular plant flora of Guthrie County, Iowa, based on field, herbarium, and literature studies, consists of748 taxa (species, varieties, and hybrids), 135 of which are naturalized. -

Plant Rank List.Xlsx

FAMILY SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME S RANK Aceraceae Acer ginnala Amur Maple SNA Aceraceae Acer negundo Manitoba Maple S5 Aceraceae Acer negundo var. interius Manitoba Maple S5 Aceraceae Acer negundo var. negundo Manitoba Maple SU Aceraceae Acer negundo var. violaceum Manitoba Maple SU Aceraceae Acer pensylvanicum Striped Maple SNA Aceraceae Acer rubrum Red Maple SNA Aceraceae Acer spicatum Mountain Maple S5 Acoraceae Acorus americanus Sweet Flag S5 Acoraceae Acorus calamus Sweet‐flag SNA Adoxaceae Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel S1 Alismataceae Alisma gramineum Narrow‐leaved Water‐plantain S1 Alismataceae Alisma subcordatum Common Water‐plantain SNA Alismataceae Alisma triviale Common Water‐plantain S5 Alismataceae Sagittaria cuneata Arum‐leaved Arrowhead S5 Alismataceae Sagittaria latifolia Broad‐leaved Arrowhead S4S5 Alismataceae Sagittaria rigida Sessile‐fruited Arrowhead S2 Amaranthaceae Amaranthus albus Tumble Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus blitoides Prostrate Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus hybridus Smooth Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus retroflexus Redroot Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus spinosus Thorny Amaranth SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus tuberculatus Rough‐fruited water‐hemp SU Anacardiaceae Rhus glabra Smooth Sumac S4 Anacardiaceae Toxicodendron rydbergii Poison‐ivy S5 Apiaceae Aegopodium podagraria Goutweed SNA Apiaceae Anethum graveolens Dill SNA Apiaceae Carum carvi Caraway SNA Apiaceae Cicuta bulbifera Bulb‐bearing Water‐hemlock S5 Apiaceae Cicuta maculata Water‐hemlock S5 Apiaceae Cicuta virosa Mackenzie's -

Evolution of the White Mountain Magnia Series

EVOLUTION OF THE WHITE MOUNTAIN MAGNIA SERIES RaNoor.pn W. CnapuaN, Vassar College CnenrBs R. wrr";;: , Cambri.d,ge,Mass. PART I. DATA Pnosr.BM In recent years, a number of intensive field and laboratory studies of the rocks of the White Mountain district in New Hamp- shire have been carried out. One result of these investigations is to show that there exists in this area a group of rocks with marked alkaline affinities (3)* to which the name White Mountain magma serieshas been applied (5, p.56). The various rock types of this group form a definite series,and wherever found in the area they possessthe same relative ages.Such a sequenceis of greatestim- portance to petrology and necessitatesan explanation. Accord- ingly, the writers have undertaken a study of this problem, the results of which are presented in this paper. ft is not pretended that this work is complete or that the problem has been entirely solved. Certain definite conclusions have been reached, however, and it is hoped that these may lead to a more complete under- standing of the evolution of the White Mountain magma series. The writers are especiallyindebted to ProfessorMarland Billings of Harvard University for his valuable assistancein preparing this paper. Several of the major ideas presentedhere were first sug- gested by Professor Billings, and these have led to a clearer under- standing of many of the intricate problems encountered in the course of the work. The writers also wish to thank ProfessorEsper S. Larsen, Jr., and ProfessorR. A. Daly for their many helpful suggestionsand criticisms.