The Main Features and the Key Challenges of the Education System in Taiwan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Impact of English Language Policy in Taiwan

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 5-2-2021 Evolution and Impact of English Language Policy in Taiwan Kaitlin Ashleigh Rigby University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons Recommended Citation Rigby, Kaitlin Ashleigh, "Evolution and Impact of English Language Policy in Taiwan" (2021). Honors Theses. 1732. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1732 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVOLUTION AND IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE POLICY IN TAIWAN By Kaitlin Ashleigh Rigby A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford, MS May 2021 Approved By ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Cheng-Fu Chen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Zhini Zeng ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Joshua Howard i © 2021 Kaitlin Ashleigh Rigby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT This thesis takes a look at how English language policy (ELP) in Taiwan has changed over time and how it has affected the education system. This thesis also investigates the different attitudes directed toward ELP, some areas of concern, and problems that have occurred as a result of Taiwan’s approach toward ELP. Understanding why Taiwan supports the English language as much as it does while also considering its approach to implementing policy will provide insight on how Taiwan believes that the ELP is a necessary part of globalization. -

Brief Introduction to Technology Education in Taiwan

Preface Technology Education at both elementary and secondary schools levels has become an important means to develop citizens' technological literacy for all worldwide. In Taiwan, Living Technology is also necessary to be energetically offered at both elementary and secondary school levels in order to improve technological literacy of the public. This brief introduction is to present the national status of technological literacy education at both elementary and secondary school levels, and provides examples of schools, written by school teachers, in the hope that domestic and international people will gain a better understanding of the ideal and reality of this field. We would like to acknowledge the support of funds for facilitating academic performances from the National Taiwan Normal University. Also, thanks to hardworking authors and editors. All of them are essential to the publication of this brief introduction. Lung-Sheng Steven Lee (Professor & Dean) July 2004 1 The National Status The Overview of Technology Education in Taiwan The Technology Education in Kindergartens, Elementary Schools, and Junior High Schools Technology Education at the Senior High School Level Technology Teacher Education Professional Associations and Events of Technology Education Examples of Schools The Affiliated Kindergarten of National Taiwan Normal University Taipei Municipal Jianan Elementary School Taichung Municipal Li Ming Elementary School Taipei Municipal Renai Junior High School Taipei Municipal Jinhua Junior High School The Affiliated Senior -

What Can We Learn from Taiwanese Teachers About Teaching Controversial Public Issues

Journal of International Social Studies, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2016, 37-52. What Can We Learn from Taiwanese Teachers about Teaching Controversial Public Issues Yu-Han Hung ([email protected]) Michigan State University, Curriculum and Instruction, Teacher Education (CITE) __________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: This study explores how history teachers in Taiwan make curricular decisions while engaging controversial public issues. The main political controversies discussed in Taiwanese society center on the relationship between Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China. This study documents how four social studies teachers formulate their curricular decisions through the intersecting lenses of professional knowledge and personal beliefs. Findings illuminate the role of personal experience and belief in teacher’s curricular-instructional gate keeping in socially divisive contexts. In sum, this study helps us understand the relationship between a teacher’s own imaginative worldview, sense of personal and professional identity and their classroom teaching practices. Key words: history curriculum, teacher knowledge, curricular-instructional gatekeeper, controversial public issues, Taiwan and the PRC __________________________________________________________________________________ As someone who has grown up, been educated, and taught high school social studies in Taiwan, I have known the controversy that envelopes that island my whole life. Now, teaching and doing research in the United States, my view is different. I have noticed that people outside of Taiwan tend to have a limited understanding of Taiwan’s relationship with the the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In contrast, for my family, friends and colleagues still living in Taiwan, the relationship with the People’s Republic of China is not only a major political issue, but a daily reality that affects almost every major aspect of their life. -

Achievements of MCU Representative Sport Teams at 2016-17 University Championship Competitions

Achievements of MCU Representative Sport Teams at 2016-17 University Championship Competitions Serial Participant Name of Competition Date & Venue Place No. s 2016-17 Taiwan University December 7-10, 2016 First Place in 2 1 Petanque Championship TianMu Petanque Field Mixed Teams 2016-17 Taiwan University December 7-10, 2016 First Place in 3 2 Petanque Championship TianMu Petanque Field Women’s Triples 2016-17 Taiwan University December 7-10, 2016 First Place in 2 3 Petanque Championship TianMu Petanque Field Women’s Doubles 2016-17 Taiwan University December 7-10, 2016 First Place in 2 4 Petanque Championship TianMu Petanque Field Women’s Doubles 2016-17 Taiwan University December 7-10, 2016 First Place in 1 5 Petanque Championship TianMu Petanque Field Women’s Triples 2017 Taiwan University First Place in Women’s Team 4 May 7-10, 2017 6 Sports Festival- Fencing Epee National Taiwan University Championship 2017 Taiwan University First Place in Women’s 1 May 7-10, 2017 7 Sports Festival- Fencing Individual Epee National Taiwan University Championship 2017 Taiwan University May 6-10, 2017 First Place in Women’s 1 8 Sports Festival- Woodball National Taipei University of Nursing Individual Stroke Championship and Health Sciences 2017 Taiwan University May 6-10, 2017 First Place in Women’s 1 9 Sports Festival- Woodball National Taipei University of Nursing Individual Fairway Championship and Health Sciences 2016 National Chung-Cheng First Place in University 16 Cup University and Oct. 15-26, 2016 Women’s A Level 2 10 Secondary School Miaoli County Stadium Basketball Championship “Cheer for Summer First Place in Dancing 9 Dec. -

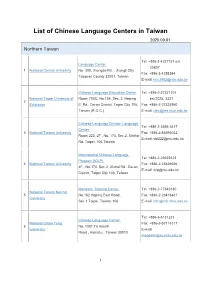

List of Chinese Language Centers in Taiwan 2020.09.01

List of Chinese Language Centers in Taiwan 2020.09.01 Northern Taiwan Tel: +886-3-4227151 ext. Language Center 33807 1 National Central University No. 300, Jhongda Rd. , Jhongli City , Fax: +886-3-4255384 Taoyuan County 32001, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] Chinese Language Education Center Tel: +886-2-27321104 National Taipei University of Room 700C, No.134, Sec. 2, Heping ext.2025, 3331 2 Education E. Rd., Da-an District, Taipei City 106, Fax: +886-2-27325950 Taiwan (R.O.C.) E-mail: [email protected] Chinese Language Division Language Tel: +886-2-3366-3417 Center 3 National Taiwan University Fax: +886-2-83695042 Room 222, 2F , No. 170, Sec.2, XinHai E-mail: [email protected] Rd, Taipei, 106,Taiwan International Chinese Language Tel: +886-2-23639123 Program (ICLP) 4 National Taiwan University Fax: +886-2-23626926 4F., No.170, Sec.2, Xinhai Rd., Da-an E-mail: [email protected] District, Taipei City 106, Taiwan Mandarin Training Center Tel: +886-2-77345130 National Taiwan Normal 5 No.162 Hoping East Road , Fax: +886-2-23418431 University Sec.1 Taipei, Taiwan 106 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +886-3-5131231 Chinese Language Center National Chiao Tung Fax: +886-3-57114317 6 No. 1001 Ta Hsueh University E-mail: Road , Hsinchu , Taiwan 30010 [email protected] 1 Chinese Language Center Tel: +886-2-2938-7141/7142 No.64, Sec. 2, Zhinan Rd., Wenshan Fax: +886-2-2939-6353 7 National Chengchi University District E-mail: Taipei City 11605, Taiwan (R.O.C.) [email protected] Tel: +886-2-2700-5858 Mandarin Learning Center ext.8131~8136 8 Chinese Culture University 4F , No.231, Sec.2, Chien-Kuo S. -

Study in Taiwan - 7% Rich and Colorful Culture - 15% in Taiwan, Ancient Chinese Culture Is Uniquely Interwoven No.7 in the Fabric of Modern Society

Le ar ni ng pl us a d v e n t u r e Study in Foundation for International Cooperation in Higher Education of Taiwan (FICHET) Address: Room 202, No.5, Lane 199, Kinghua Street, Taipei City, Taiwan 10650, R.O.C. Taiwan Website: www.fichet.org.tw Tel: +886-2-23222280 Fax: +886-2-23222528 Ministry of Education, R.O.C. Address: No.5, ZhongShan South Road, Taipei, Taiwan 10051, R.O.C. Website: www.edu.tw www.studyintaiwan.org S t u d y n i T a i w a n FICHET: Your all – inclusive information source for studying in Taiwan FICHET (The Foundation for International Cooperation in Higher Education of Taiwan) is a Non-Profit Organization founded in 2005. It currently has 114 member universities. Tel: +886-2-23222280 Fax: +886-2-23222528 E-mail: [email protected] www.fichet.org.tw 加工:封面全面上霧P 局部上亮光 Why Taiwan? International Students’ Perspectives / Reasons Why Taiwan?1 Why Taiwan? Taiwan has an outstanding higher education system that provides opportunities for international students to study a wide variety of subjects, ranging from Chinese language and history to tropical agriculture and forestry, genetic engineering, business, semi-conductors and more. Chinese culture holds education and scholarship in high regard, and nowhere is this truer than in Taiwan. In Taiwan you will experience a vibrant, modern society rooted in one of world’s most venerable cultures, and populated by some of the most friendly and hospitable people on the planet. A great education can lead to a great future. What are you waiting for? Come to Taiwan and fulfill your dreams. -

A Reflective Self-Inquiry Into My Teaching Practices with Non-English-Major Technological University Students

Canadian Journal of Action Research Volume 14, Issue 3, 2013, pages 59-71 A REFLECTIVE SELF-INQUIRY INTO MY TEACHING PRACTICES WITH NON-ENGLISH-MAJOR TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY STUDENTS Chiu-Kuei Chang Chien, WuFeng University, Taiwan Kuo-Jen Yu, Nanhua University, Taiwan Lung-Chi Lin, Kao Yuan University, Taiwan ABSTRACT Action research allows teachers to evaluate and gain insight into their own practices in their teaching contexts through reflection, and inquire into ways to improve their practices and student learning outcomes. This study is a reflective self-inquiry in which the research team engages in a deliberate and retrospective analysis of the principal investigator’s teaching practices. The purpose is to identify possible factors that cause the low performance of non- major “English as a Foreign Language” students in her university English classes and propose alternative instructional practices and evaluative measures to manage their learning problems. INTRODUCTION Action research allows teachers to gain insight into their own practices in their teaching contexts through reflection and evaluation, and to inquire into methods that can help improve student practices and learning outcomes. It comprises a broad spectrum of approaches to action, change, and inquiries. One form of action research is self-reflective inquiry by which practitioners seek to solve problems, improve practices, and enhance their understanding of their own contexts (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988; Nunan, 1992). Inquiry is intrinsically a behavior or course of finding -

Taiwan Language-In-Education Policy: Social, Cultural, and Practical Implications

Arizona Working Papers in SLA & Teaching, 20, 76- 95 (2013) TAIWAN LANGUAGE-IN-EDUCATION POLICY: SOCIAL, CULTURAL, AND PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS Elizabeth Hubbs University of Arizona In recent years, Taiwan language-in-education policy has greatly transformed and become the subject of much research (Oladejo, 2006; Sandel, 2003; Tsao, 1999). Previously, monolingual policies under Japan and the Kuomintang1 demonstrated that language was a symbolic tool to build nationalism and create social hegemony (Bourdieu, 1991). After these policies faded out in the early 1990s, Taiwan began to incorporate multilingual education, promoting internationalization through English as a foreign language and Taiwanisation through the introduction of local and indigenous languages in schools (Beaser, 2006; Sandel, 2003). The paper examines the launching of these two movements in education by discussing their development through history, current policy implementation, and the linguistic orientations of the surrounding communities. Rather than draw conclusions, the study ends by asking how indigenous scholarship and knowledge can be further integrated and validated in Taiwan’s education system, and how critical perspectives can be used to understand language policy and indigenous education in an increasingly globalized world. INTRODUCTION The field of language planning and policy (LPP) in Taiwan has received significant attention over the past twenty-five years (Sandel, 2003). During this time frame, Taiwan has shifted from a country that promoted a monolingual national language policy, to one that seeks to develop societal multilingualism and internationalization. This shift has sparked an increasing interest for researchers to document and characterize the changes, development, and implementation of current LPP in Taiwan (Sandel, 2003; Wu, 2011). -

The Intention of General Education in Taiwan's Universities

Journal of Education and Learning; Vol. 7, No. 2; 2018 ISSN 1927-5250 E-ISSN 1927-5269 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Intention of General Education in Taiwan’s Universities: To Cultivate the Holistic Person Yi-Huang Shih1, Jen-Pin Hsu2 & Yan-Hong Ye3 1 Department of Early Child Educare, Ching Kuo Institute of Management and Health, Keelung, Taiwan 2 Jian-De Junior High School, Keelung, Taiwan 3 Teacher Education Center, Ming Chuan University, Taipei, Taiwan Correspondence: Yi-Huang Shih, Department of Early Child Educare, Ching Kuo Institute of Management and Health, Keelung, Taiwan. Tel: 886-2-2437-2093. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 10, 2017 Accepted: January 8, 2018 Online Published: February 11, 2018 doi:10.5539/jel.v7n2p287 URL: http://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v7n2p287 Abstract The cultivation of the holistic person has always been a topic of concern for general education in Taiwan’s universities. Hopefully students can attain a more perfect human nature. So the question is how to practice general education to cultivate the holistic person. This is the focus of this article. After reading and analyzing related studies, the strategies for cultivating the holistic person we identified are as follows: (1) concern about students’ knowledge integration and moral manifestation, (2) cultivation of students’ human nature, (3) concern with students’ life experiences, and (4) general education is as important as professional education. Hopefully the discussion in this article will provide some ideas to help Taiwan's current general education practices, and allow us to realize the ideal of general education, i.e., the cultivation of the holistic person. -

Taiwan's Language Curriculum and Policy: a Rhetorical Analysis of the DPP's Claims-Making

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2009 Taiwan's language curriculum and policy: A rhetorical analysis of the DPP's claims-making Yi-Hsuan Lee University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2009 Yi-Hsuan Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Language and Literacy Education Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Yi-Hsuan, "Taiwan's language curriculum and policy: A rhetorical analysis of the DPP's claims- making" (2009). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 670. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/670 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAIWAN'S LANGUAGE CURRICULUM AND POLICY: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE DPP'S CLAIMS-MAKING A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Approved: Dr. Robert Boody, Committee Chair Dr. John Fritch, Committee Member Dr. Kent Sandstrom, Committee Member Dr. Kimberly Knesting, Committee Member Dr. Sarina Chen, Committee Member Yi-Hsuan Lee University of Northern Iowa December 2009 UMI Number: 3392894 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Language Planning and Policy in Taiwan: Past, Present, and Future

Working Papers in Educational Linguistics (WPEL) Volume 24 Number 2 Special Issue on Language Policy Article 5 and Planning Fall 2009 Language Planning and Policy in Taiwan: Past, Present, and Future Ming-Hsuan Wu University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/wpel Part of the Education Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Wu, M. (2009). Language Planning and Policy in Taiwan: Past, Present, and Future. 24 (2), Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/wpel/vol24/iss2/5 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/wpel/vol24/iss2/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Language Planning and Policy in Taiwan: Past, Present, and Future This article is available in Working Papers in Educational Linguistics (WPEL): https://repository.upenn.edu/wpel/ vol24/iss2/5 Language Planning and Policy in Taiwan: Past, Present, and Future Ming-Hsuan Wu University of Pennsylvania This paper takes a language ecology perspective (Haugen, 1972; Hornberger, 2003) and uses Cooper’s language planning framework for status planning, ac- quisition planning and corpus planning (1989) to provide an overview analysis of language policy and planning (LPP) in Taiwan since the 17th century. The paper investigates how languages have interacted with one another and with their socio- cultural and political contexts, and how different policies at different times have altered the local language ecology. Three emerging factors that are changing the local ecology are further identified. As the first step to successful LPP is a detailed understanding of the local language ecology (Kaplan & Baldauf, 2008), it is hoped that the analysis presented here will provide insights for future LPP in Taiwan. -

A Study on the Development of Advanced Faculty in Leisure and Sport for Higher Education Between 2006 and 2011

A Study on the Development of Advanced Faculty in Leisure and Sport for Higher Education between 2006 and 2011 Cheng-Lung Wu, Department of Marine Sports and Recreation, National Penghu University of Science and Technology, Taiwan Yung-Chuan Tsai, Department of Recreation Sports & Health Promotion, Meiho University, Taiwan Yong Tang, Corresponding Author, Department of Aquatic Sport and Recreation, Taipei College of Maritime Technology, Taiwan ABSTRACT This study employed latent growth curve modeling to verify the growth on the number of full-time faculty in the department relevant to leisure and sports in higher educational institutions in Taiwan. The scope of this study covers the departments relevant to leisure and sport. The number of the full-time faculty in the department relevant to leisure and sport was treated as observed variable for the analysis of its growth. The results found that a goodness fit between the number of students recruited in the latent growth curve model and observed data and that the growth of the number of the faculty in the department relevant to leisure and sport was significantly different along with time and the increase of the number of classes in the department relevant to the leisure and sport. And, the number of the faculty in the department relevant to leisure and sport in between 2006 and 2011 was significantly impacted by the higher educational systems, traditional or vocational universities, both of the number in the beginning point and growth rate were significantly different. It revealed that the factor of traditional and vocational educational system did influence the number of full-time faculty.