Environmental Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Many Online Quizzes at URL Below

BreakingNewsEnglish - Many online quizzes at URL below Onion emergency in True / False a) Onions are a staple in Bangladeshi cuisine. T Bangladesh / F 21st November, 2019 b) The article said Bangladesh is importing onions from Iran. T / F Onions are very c) The price of onions has increased nearly ten- important in fold in Bangladesh. T / F Bangladeshi cuisine. The vegetable is a d) The opposition party in Bangladesh has asked staple in the people to protest. T / F country's cooking. e) Bangladesh's Prime Minister is still cooking her However, many meals using onions. T / F people are finding it difficult to buy f) Some onions are on sale in markets in Dhaka onions. There is a for double the usual price. T / F shortage of them, g) A Dhaka resident said she hadn't bought which means prices onions in over two weeks. T / F have rocketed. Many Bangladeshis simply cannot afford to buy onions. Bangladesh traditionally h) Street-food sellers still have enough onions to imports onions from its neighbour India. Recent make their snacks. T / F heavy monsoon rains in India damaged a lot of India's onion harvest. This has made India ban exports to Bangladesh. The price of one kilogram of Synonym Match onions in Bangladeshi markets has risen from US36 (The words in bold are from the news article.) cents to around $3.25. This is nearly a ten-fold 1. cuisine a. scarcity increase. Bangladesh's opposition party has called for nationwide protests over the record prices. 2. shortage b. nibbles The onion crisis is so serious that even the Prime 3. -

TASTE of SOUTH EAST ASIA by Chef Devagi Sanmugam

TASTE OF SOUTH EAST ASIA by Chef Devagi Sanmugam COURSE CONTENT WORKSHOP 1 – CHINESE CUISINE (19th September 2013) Introduction to Chinese cuisine eating habits and food culture Ingredients commonly used in Chinese cooking Art of using wok and cooking with a wok Featured Recipes Spring Rolls Salt Baked Chicken Sweet and Sour Prawns with Pineapple Stir Fried Mixed Vegetables Steamed Fish Hakka Noodles WORKSHOP 2 – THAI AND VIETNAMESE CUISINE (20th September 2013) Introduction to Thai and Vietnamese cuisine eating habits and food culture Ingredients commonly used in Thai and Vietnamese cooking Making of curry pastes and dips Featured Recipes Vietnamese Beef Noodles Green curry chicken Caramelized Poached Fish Mango Salad Pineapple Rice WORKSHOP 3 – INDIAN AND SRI LANKAN CUISINE (21st September 2013) Introduction to Indian cuisine eating habits and food culture Ingredients commonly used in Indian cooking Art of using and blending spices, medicinal values and storage Featured Recipes Cauliflower Pakoras Peshawari Pilau Tandoori Chicken Prawns Jalfrezi Mixed Fruits Raita WORKSHOP 4 – JAPANESE, KOREAN AND FILIPINO CUISINE (22nd September) Brief introduction to Japanese, Korean and Filipino cuisine eating habits and food culture Ingredients commonly used in above cooking Featured Recipes Chicken Yakitori Bulgogi Chicken Adobo in coconut milk Teriyaki Salmon Korean Ginseng Soup WORKSHOP 5 – MALAYSIAN, INDONESIAN AND BALINESE (23rd September) Introduction to Malaysian, Indonesian and Balinese cuisine eating habits and food culture Ingredients commonly used in above cooking Herbs and spices used in above cuisine Featured Recipes Sate Lembu Nasi Kunyit Lamb Rendang Sambal Udang Eurasian Cabbage Roll WORKSHOP 6 – STREET FOODS OF ASIA (24th September 2013) Introduction to Streets foods of Asia eating habits and food culture Ingredients commonly used and eating habits Featured Recipes Chicken Rice (Singapore) Potato Bonda (India) Garlic Chicken Wings (Thailand) Roti John (Malaysia) Fresh Spring Rolls (Vietnam) . -

Forthcoming in Environmental Values. ©2020 the White Horse Press

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 The ABCs of relational values: environmental values that include aspects of both intrinsic and instrumental valuing Deplazes-Zemp, Anna ; Chapman, Mollie Abstract: In this paper we suggest an interpretation of the concept of ‘relational value’ that could be useful in both environmental ethics and empirical analyses. We argue that relational valuing includes aspects of intrinsic and instrumental valuing. If relational values are attributed, objects are appreciated because the relationship with them contributes to the human flourishing component of well-being (instrumental aspect). At the same time, attributing relational value involves genuine esteem for the valued item (intrinsic aspect). We also introduce the notions of mediating and indirect relational environmental values, attributed in relationships involving people as well as environmental objects. We close by proposing how our analysis can be used in empirical research. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3197/096327120x15973379803726 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-191717 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Deplazes-Zemp, Anna; Chapman, Mollie (2020). The ABCs of relational values: environmental values that include aspects of both intrinsic and instrumental valuing. Environmental Values:Epub ahead of print. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3197/096327120x15973379803726 Forthcoming in Environmental Values. ©2020 The White Horse Press www.whpress.co.uk THE A, B, C’S OF RELATIONAL VALUES: ENVIRONMENTAL VALUES THAT INCLUDE ASPECTS OF BOTH INTRINSIC AND INSTRUMENTAL VALUING Anna Deplazes-Zemp1*, Mollie Chapman2 1 Ethics Research Institute (ERI), University of Zurich, Zollikerstrasse 117, CH-8008 Zurich, Switzerland 2 Department of Geography, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstr. -

Vientiane FOOD GUIDE

ASIA FOODD GUIDE:: LAO PPDRD Vientiane THE LOCALS MUST KNOW LAO PDR | 1 INTRODUCTION Welcome to Asia! We are as passionate about food as we are with the law. And no one knows local food better than those who walk the ground. In our Rajah & Tann Asia Food Guide series, our lawyers are delighted to share with you their favourite dishes in the heart of the cities where we operate and give you a taste of the delightful food the region has to offer. We bring you to savour the most authentic Asian food including under- the-radar eateries that only locals will frequent. This is our home ground, our advantage. LAO PDR | 3 Lao PDR 1. SAI AUA Laotian cuisine is extremely “This Lao pork flavourful and is influenced by sausage is a delicious geographical proximity and combination of pork, chilli, lemongrass, kaffir history. Laos offers more than leaves and shallots 3,000 traditional rice varieties – prepared with a blend of spices and local herbs." for example, sticky rice is a staple food in lowland Laos. In Laos, it is also common to find the local food flavoured with galangal, lemongrass LEE Hock Chye Managing Partner and Lao fish sauce. Rajah & Tann (Laos) 2. KOI PA KERG A pleasing feature found in Laotian Try it at: “This Mekong fish is cooked and cuisine is the fresh raw vegetables Khua Mae Ban mixed with spice, chillies, onions, and herbs often served on the side Hom 4, Ban Phonsawang, and local Lao herbs. The unique Vientiane recipe is perfected at Soukvimarn with other dishes. -

Environmental Studies and Utilitarian Ethics

Environmental Studies and Utilitarian Ethics Brian G. Wolff University of Minnesota Conservation Biology Program,100 Ecology Building 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 55108 Email: [email protected] Abstract: Environmental ethicists have focused much attention on the limits of utilitarianism and have generally defined “environmental ethics” in a manner that treats utilitarian environmental ethics as an oxymoron. This is unfortunate because utilitarian ethics can support strong environmental policies, and environmental ethicists have not yet produced a contemporary environmental ethic with such broad appeal. I believe educators should define environmental ethics more broadly and teach utilitarian ethics in a non-pejorative fashion so that graduates of environmental studies and policy programs understand the merits of utilitarian arguments and can comfortably participate in the policymaking arena, where utilitarian ethics continue to play a dominant role. Keywords: Environmental Education, Environmental Studies, Environmental Ethics, Utilitarianism, Utilitarian Ethics Introduction an antipathy for utilitarian ethics. To prepare graduates of environmental science courses for The current generation of college students is participation in the policy process, it is important that expected to witness a dramatic decline in environmental biologists teach the strengths, as well biodiversity, the continued depletion of marine as the weaknesses, of utilitarian ethics in a non- fisheries, water shortages, extensive eutrophication of pejorative fashion, and the limitations, as well as the freshwater and marine ecosystems, a dramatic decline strengths, of competing theories. in tropical forest cover, and significant climatic It must be appreciated that the training given warming (Jenkins 2003, Pauly et al. 2002, Jackson et most biologists seldom includes rigorous courses in al. -

Talking Taste

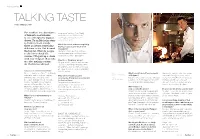

EAT TOGETHER TAlking TAste WRITEr : KIMBERLEY LOVATO For ‘foodies’, the abundance cheese and a whisky. Chef Freddy of fantastic restaurants Vandecasserie of La Villa Lorraine is one of Belgium’s biggest was the greatest influence in my draws. From Michelin stars professional career. to hidden snack stands, What’s the most embarrassing thing there is always something that has happened to you in your delicious to try. But beyond restaurant? the border, what do people Having a Flemish guest speak to me, really know about the and only nodding and smiling because cuisine ? We pull up a chair I had no idea what he was saying with four Belgian chefs who What does ‘Chambar’ mean ? are also making a name My grandmother came up with the name for themselves abroad. - an old French phrase meaning ‘when the teacher leaves the room, all the kids go crazy!’ In French it is spelt chambard NICOLAS SCHUERMANS - the ‘d’ is silent. Nicolas Schuermans, ‘Nico’ to his friends Left : What is your fondest food memory than waffles and chocolate! For example, Nicolas Scheurmans and family, studied at the prestigious What advice would you give of Belgium ? I have rabbit or pigeon on my winter CREPAC School of Culinary Arts to someone dining at your restaurant R i g h t : My dad’s whole braised squab with baby menu, something Americans rarely eat. Bart M. Vandaele in Belgium and apprenticed at La Villa for the first time ? potatoes. The best squabs always came Shrimp croquettes are a favourite. Lorraine (two Michelin stars), before Be open-minded and without from my granddad’s pigeon house. -

Trauma, Gender, and Traditional Performance In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Art of Resistance: Trauma, Gender, and Traditional Performance in Acehnese Communities, 1976-2011 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Women’s Studies by Kimberly Svea Clair 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Art of Resistance: Trauma, Gender, and Traditional Performance in Acehnese Communities, 1976-2011 by Kimberly Svea Clair Doctor of Philosophy in Women’s Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Susan McClary, Chair After nearly thirty years of separatist conflict, Aceh, Indonesia was hit by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, a disaster that killed 230,000 and left 500,000 people homeless. Though numerous analyses have focused upon the immediate economic and political impact of the conflict and the tsunami upon Acehnese society, few studies have investigated the continuation of traumatic experience into the “aftermath” of these events and the efforts that Acehnese communities have made towards trauma recovery. My dissertation examines the significance of Acehnese performance traditions—including dance, music, and theater practices—for Acehnese trauma survivors. Focusing on the conflict, the tsunami, political and religious oppression, discrimination, and hardships experienced within the diaspora, my dissertation explores the ii benefits and limitations of Acehnese performance as a tool for resisting both large-scale and less visible forms of trauma. Humanitarian workers and local artists who used Acehnese performance to facilitate trauma recovery following the conflict and the tsunami in Aceh found that the traditional arts offered individuals a safe space in which to openly discuss their grievances, to strengthen feelings of cultural belonging, and to build solidarity with community members. -

Burmese Cusine: on the Road to Flavor

Culinary Historians of Washington, D.C. September 2014 Volume XIX, Number 1 Save these 2014-15 CHoW Meeting Dates: Burmese Cusine: On the Road to Flavor September 14 Speaker: John Tinpe October 12 Sunday, September 14 November 9 2:30 to 4:30 p.m. December 14 Bethesda-Chevy Chase Services Center, January 11, 2015 4805 Edgemoor Lane, Bethesda, MD 20814 February 8, 2015 NOTE: This is the March 8, 2015 here’s nothing like last CHoW Line until it. A true cross- September. April 12, 2015 May 3, 2015 Troads cuisine, the food of Burma (Myan- Have a nice summer! John Tinpe is the longtime owner mar), though influenced of Burma Restaurant in China- by the culinary flavors of Renew Your town. His maternal ancestors China, India, Laos, and Membership in belonged to the Yang Dynasty, Thailand, is unique. including one whose title was lord Burmese cuisine is CHoW NOW prince in Kokang province. His most famous for its un- for 2014-15! father was a top diplomat, serving usual fermented green as deputy permanent represen- tea leaf salad (lahpet), The membership year tative to the United Nations. A rice vermicelli and fish runs from September 1 graduate of Bucknell University, soup (mohinga, the “na- to August 31. Annual John has been a resident of Wash- tional dish”); fritters, dues are $25 for ington since 1991. For leisure he curries, noodles, vege- individuals, households, enjoys Dragon Boat racing. He tables, and meat dishes; also worked at the John F. Ken- and semolina, sago, and coconut milk sweets. The or organizations. -

PLACES to EAT SEPTEMBER 10, 2019 BREAKFAST H Staff Favorites LUNCH/DINNER (Cont’D)

NORTH COAST COLLEE CREER EPO PLACES TO EAT SEPTEMBER 10, 2019 BREAKFAST H Staff Favorites LUNCH/DINNER (Cont’d) $$$ Los Bagels — 403 2nd St., Eureka or 1061 I St., Arcata $$$ Rita’s Mexican Grill — 855 8th St, Arcata/427 W Harris St, Eka H Multicultural Mexican-Jewish bakery. Organic bagels, all the toppings and coffee. H Harris location is close to the Expo and the Arcata location is just off the Plaza. $$$ Big Blue Café — 846 G St., Arcata $$$ Wildflower Café & Bakery —1604 G St, Arcata H Best huevos rancheros & homemade apple juice. H Vegetarian eatery featuring locally sourced ingredients. $$$ Renatas Creperia — 1030 G St., Arcata $$$ Ramones Bakery & Café — 2297 Harrison Ave., Eureka H Artsy eatery featuring sweet & savory crepes, salads, espresso & mimosas. H Local café and artisan bakery serving breakfast, lunch and dinner. Outdoor patio. $$$ Café Nooner — 2910 E St., Eureka & 409 Opera Alley, Eureka $$$ The Lighthouse Grill — 355 Main St, Trinidad H As seen on Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives. Serves breakfast, lunch and dinner. H Everything fresh & homemade. Try the mashed potatoes and brisket in a savory waffle cone! $$$ The Greene Lily — 307 2nd St, Eureka $$$ Arcata Pizza Deli (APD) — 1057 H St., Arcata H Classic comfort food and award winner of best mimosa 2018. H Large portions of pizza, hamburgers, hot sandwiches, fries, and salads. $$$ T’s North Café — 860 10th St., Arcata $$$ Humboldt Soup Company — 1019 Myrtle Avenue, Eureka H Breakfast and lunch, many GF options. Best eggs benedict and mimosa menu! H Mix-n-match soups, sandwiches and salads. Dine-in, take-out or drive-thru. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Richard Dawkins

RICHARD DAWKINS HOW A SCIENTIST CHANGED THE WAY WE THINK Reflections by scientists, writers, and philosophers Edited by ALAN GRAFEN AND MARK RIDLEY 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Oxford University Press 2006 with the exception of To Rise Above © Marek Kohn 2006 and Every Indication of Inadvertent Solicitude © Philip Pullman 2006 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should -

Bangladeshi Cuisine Is Rich and Varied with the Use of Many Spices

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions following it (1-3). Bangladeshi cuisine is rich and varied with the use of many spices. We have delicious and appetizing food, snacks, and sweets. Boiled rice is our staple food. It is served with a variety of vegetables, curry, lentil soups, fish and meat. Fish is the main source of protein. Fishes are now cultivated in ponds. Also we have fresh-water fishes in the lakes and rivers. More than 40 types of fishes are common, Some of them are carp, rui, katla, magur (catfish), chingri (prawn or shrimp), Shutki or dried fishes are popular. Hilsha is very popular among the people of Bangladesh. Panta hilsha is a traditional platter of Panta bhat. It is steamed rice soaked in water and served with fried hilsha slice, often together with dried fish, pickles, lentil soup, green chilies and onion. It is a popular dish on the Pohela Boishakh. The people of Bangladesh are very fond of sweets. Almost all Bangladeshi women prepare some traditional sweets. ‘Pitha’ a type of sweets made from rice, flour, sugar syrup, molasses and sometimes milk, is a traditional food loved by the entire population. During winter Pitha Utsab, meaning pitha festival is organized by different groups of people, Sweets are distributed among close relatives when there is good news like births, weddings, promotions etc. Sweets of Bangladesh are mostly milk based. The common ones are roshgulla, sandesh, rasamalai, gulap jamun, kaljamun and chom-chom. There are hundreds of different varieties of sweet preparations. Sweets are therefore an important part of the day-to-day life of Bangladeshi people.