Freyermuth Ku 0099D 16682

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRIVATE AFFAIR, INC. Russo Predicts the -Break in Image That Will Succeed with a Mass American Audience Will Probably Come Through a Film Like Cabaret Frontrunner

RUSSO~------ History of a Nameless Minority in Film."' continued from page 1 Even under that cover the program drew never explained." the ire of the state governor and blasts from European films were not made under the Manchester Union Leader. these restrictions, however, and audiences "That got me started. Obviously began to accept such movies as Victim, something had to be done. My aim was to Taste of Honey and The L-Shaped Room, point out to people-especially gay people Can I Have Two Men Kissing? Russo says. When Otto Preminger decided -:-how social stereotypes have been created MATLOVICH ----- never shown, it will be worth it. Ten years to do Advise and Consent the Code finally by the media. The Hollywood images of gay from now people are going to see it and say, continued from page 1 gave way before the pressure of a powerful people were a first link to our own sexuality 'Is that all there was to it?"' the audience was given an insider's view in The presentation of the film relies heavily to NBC fears about presenting a positive on the hearing which ehded in Matlovich's image of gays to a national audience. dismissal from the service. Airmen testify "The film has been in the closet. When repeatedly that Matlovich was an outstan NBC is ready to come out of the closet, ding soldier and instructor and that his then the rest of America will have a better openly gay life-style would not affect their understanding of gays," Paul Leaf, direc ability to continue to work successfully with tor and producer of the .show, told the au him. -

Merchant, Jimmy Merchant, Jimmy

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 4-7-2006 Merchant, Jimmy Merchant, Jimmy. Interview: Bronx African American History Project Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Merchant, Jimmy. 7 April 2006. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewee: Jimmy Merchant Interviewers: Alessandro Buffa, Loreta Dosorna, Dr. Brian Purnell, and Dr. Mark Naison Date: April 7, 2006 Transcriber: Samantha Alfrey Mark Naison (MN): This is the 154th interview of the Bronx African American History Project. We are here at Fordham University on April 7, 2006 with Jimmy Merchant, an original and founding member of Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, who has also had a career as an artist. And with us today, doing the interviews, are Alessandro Buffa, Lorreta Dosorna, Brian Purnell, and Mark Naison. Jimmy, can you tell us a little about your family and where they came from originally? Jimmy Merchant (JM): My mom basically came from Philadelphia. My dad – his family is from the Bahamas. He – my dad – was shifted over to the south as a youngster. His mother was from the Bahamas and she moved into the South – South Carolina, something like that – and he grew up there. -

It Is Christmas Eve at a Waffle House Just Off Interstate 24 in Murfreesboro, TN, Just 20 Miles Outside of Nashville

A SCATTERED, SMOTHERED & COVERED CHRISTMAS A Waffle House Christmas Musical written by Kaine Riggan (It is Christmas Eve at a Waffle House just off Interstate 24 in Murfreesboro, TN, just 20 miles outside of Nashville. As the lights come up, wee see one gentleman sitting in a booth drinking coffee and having a bowl of chili. A quirky little waitress names Rita enters, obviously in a good mood. She is somewhere between plain and attractive and somewhere between thirty-five and fifty-five, although it is somewhat difficult to judge where in either category she clocks in. She pours out the old coffee (regular) and starts a new pot. She picks up a second pot (decaf) and smells it and decides to keep it. Suddenly, she notices the audience for the first time.) RITA Well shoot fire! If I’d known all ya’ll were gonna be here tonight, I’d a spent more time on this hair. (She quickly adjusts her hairdo) What do you think Harold? Is that better or should I just wear my bad hair day bonnet? (referring to her Waffle House paper hat) (HAROLD mumbles a grouchy, unintelligible response) Oh, chip up, Harold. It’s Christmas Eve! Don’t you just love Christmas Eve? (HAROLD starts to mumble again but she talks right over his response) Awe, there’s just something about this place on Christmas Eve. It’s magical… like there’s something special in the air. HAROLD (acknowledging himself) Sorry! RITA That is not exactly what I had in mind (shouting towards the kitchen) Bert, get in here and change this chili out. -

Jane Jayroe-Gamble She Overcame Her Fears and Shyness to Win Miss America 1967, Launching Her Career in Media and Government

Jane Jayroe-Gamble She overcame her fears and shyness to win Miss America 1967, launching her career in media and government Chapter 01 – 0:52 Introduction Announcer: As millions of television viewers watch Jane Jayroe crowned Miss America in 1967, and as Bert Parks serenaded her, no one would have thought she was actually a very shy and reluctant winner. Nor would they know that the tears, which flowed, were more of fright than joy. She was nineteen when her whole life was changed in an instant. Jane went on to become a well-known broadcaster, author, and public official. She worked as an anchor in TV news in Oklahoma City and Dallas, Fort Worth. Oklahoma governor, Frank Keating, appointed her to serve as his Secretary of Tourism. But her story along the way was filled with ups and downs. Listen to Jane Jayroe talk about her struggle with shyness, depression, and a failed marriage. And how she overcame it all to lead a happy and successful life, on this oral history website, VoicesofOklahoma.com. Chapter 02 – 8:30 Grandparents John Erling: My name is John Erling. Today’s date is April 3, 2014. Jane, will you state your full name, your date of birth, and your present age. Jane Jayroe: Jane Anne Jayroe-Gamble. Birthday is October 30, 1946. And I have a hard time remembering my age. JE: Why is that? JJ: I don’t know. I have to call my son, he’s better with numbers. I think I’m sixty-seven. JE: Peggy Helmerich, you know from Tulsa? JJ: I know who she is. -

Sinister Wisdom 70.Pdf

Sinister Sinister Wisdom 70 Wisdom 70 30th Anniversary Celebration Spring 2007 $6$6 US US Publisher: Sinister Wisdom, Inc. Sinister Wisdom 70 Spring 2007 Submission Guidelines Editor: Fran Day Layout and Design: Kim P. Fusch Submissions: See page 152. Check our website at Production Assistant: Jan Shade www.sinisterwisdom.org for updates on upcoming issues. Please read the Board of Directors: Judith K. Witherow, Rose Provenzano, Joan Nestle, submission guidelines below before sending material. Susan Levinkind, Fran Day, Shaba Barnes. Submissions should be sent to the editor or guest editor of the issue. Every- Coordinator: Susan Levinkind thing else should be sent to Sinister Wisdom, POB 3252, Berkeley, CA 94703. Proofreaders: Fran Day and Sandy Tate. Web Design: Sue Lenaerts Submission Guidelines: Please read carefully. Mailing Crew for #68/69: Linda Bacci, Fran Day, Roxanna Fiamma, Submission may be in any style or form, or combination of forms. Casey Fisher, Susan Levinkind, Moire Martin, Stacee Shade, and Maximum submission: five poems, two short stories or essays, or one Sandy Tate. longer piece of up to 2500 words. We prefer that you send your work by Special thanks to: Roxanna Fiamma, Rose Provenzano, Chris Roerden, email in Word. If sent by mail, submissions must be mailed flat (not folded) Jan Shade and Jean Sirius. with your name and address on each page. We prefer you type your work Front Cover Art: “Sinister Wisdom” Photo by Tee A. Corinne (From but short legible handwritten pieces will be considered; tapes accepted the cover of Sinister Wisdom #3, 1977.) from print-impaired women. All work must be on white paper. -

ONWARD and UPWARD Opportunity Comes in Many Forms and Two Colors, Blue and Gold

NURSING’S ACCESS WEATHERSPOON’S NANCY ADAMS, P.2 FOR VETERANS P. 24 BIG BANG P. 28 AHEAD OF HER TIME FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS SPRING 2016 Volume 17, No. 2 MAGAZINE ONWARD AND UPWARD Opportunity comes in many forms and two colors, blue and gold. PG. 12 SHOW AND TELL Students in Professor Jo Leimenstoll’s interior architecture class had the opportunity to do prospective design work for a historic downtown building. Best of all, they had the chance to speak with and learn from developers, city officials and consultants 12 such as alumna Megan Sullivan (far right in picture) as they presented their creative work. UNCG’s undergraduate program was rated No. 4 nationally in a DesignIntelligence Magazine survey of deans and department heads. See more opportunity-themed stories and photos in the Golden Opportunity feature. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARTIN W. KANE. KANE. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARTIN W. contents news front 2 University and alumni news and notes out take 8 Purple reigns in Peabody Park the studio 10 Arts and entertainment 12 Golden Opportunity UNCG provides the chance to strive for dreams and prepare to make your mark on the world. Some alumni and students share their tales of transformation. Weatherspoon’s Big Bang 24 Gregory Ivy arrived to create an art department, and ultimately de Kooning’s “Woman” was purchased as part of the Weatherspoon collection. Ahead of Her Time 28 Nancy Adams ’60, ’77 MS didn’t set out to be a pioneer. But with Dean Eberhart’s help, she became North Carolina’s first genetic counselor. -

"Woman.Life.Song" by Judith Weir Heather Drummon Cawlfield

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-1-2015 Study and analysis of "woman.life.song" by Judith Weir Heather Drummon Cawlfield Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Cawlfield, Heather Drummon, "Study and analysis of "woman.life.song" by Judith Weir" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 14. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2015 HEATHER DRUMMOND CAWLFIELD ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School STUDY AND ANALYSIS OF woman.life.song BY JUDITH WEIR A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Heather Drummond Cawlfield College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Music Performance May 2015 This Dissertation by: Heather Drummond Cawlfield Entitled: Study and Analysis of “woman.life.song” by Judith Weir has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of Performing Arts in School of Music, Program of Vocal Performance Accepted by the Doctoral Committee ______________________________________________________ Melissa Malde, D.M.A., Research Advisor ______________________________________________________ Brian Luedloff, M.F.A., Co-Research Advisor (if applicable) _______________________________________________________ Robert Ehle, Ph.D., Committee Member _______________________________________________________ Susan Collins, Ph.D., Committee Member Date of Dissertation Defense _________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _________________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. -

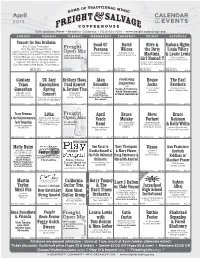

April CALENDAR of EVENTS

April CALENDAR 2013 OF EVENTS 2020 Addison Street • Berkeley, California • (510) 644-2020 • www.freightandsalvage.org SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Concert for Sue Draheim eric & Suzy Thompson, Good Ol’ David Olive & Barbara Higbie, Jody Stecher & kate brislin, Freight laurie lewis & Tom rozum, kathy kallick, Persons Wilcox the Dirty Linda Tillery Open Mic California bluegrass the best of pop Gerry Tenney & the Hard Times orchestra, pay your dues, trailblazers’ reunion and folk aesthetics Martinis, & Laurie Lewis Golden bough, live oak Ceili band with play and shmooze Hills to Hollers the Patricia kennelly irish step dancers, Girl Named T album release show Tempest, Will Spires, Johnny Harper, rock ‘n’ roots fundraiser don burnham & the bolos, Tony marcus for the rex Foundation $28.50 adv/ $4.50 adv/ $20.50 adv/ $24.50 adv/ $20.50 adv/ $22.50 adv/ $30.50 door monday, April 1 $6.50 door Apr 2 $22.50 door Apr 3 $26.50 door Apr 4 $22.50 door Apr 5 $24.50 door Apr 6 Gautam UC Jazz Brittany Haas, Alan Celebrating House The Earl Songwriters Tejas Ensembles Paul Kowert Senauke with Jacks Brothers Zen folk musician, Caren Armstrong, “the rock band Outlaw Hillbilly Ganeshan Spring & Jordan Tice featuring Keith Greeninger without album release show Carnatic music string fever Jon Sholle, instruments” with distinction Concert from three Chad Manning, & Steve Meckfessel and inimitable style featuring the Advanced young virtuosos Suzy & Eric Thompson, Combos and big band Kate Brislin $20.50/$22.50 Apr 7 $14.50/$16.50 Apr -

James Taylor

JAMES TAYLOR Over the course of his long career, James Taylor has earned 40 gold, platinum and multi- platinum awards for a catalog running from 1970’s Sweet Baby James to his Grammy Award-winning efforts Hourglass (1997) and October Road (2002). Taylor’s first Greatest Hits album earned him the RIAA’s elite Diamond Award, given for sales in excess of 10 million units in the United States. For his accomplishments, James Taylor was honored with the 1998 Century Award, Billboard magazine’s highest accolade, bestowed for distinguished creative achievement. The year 2000 saw his induction into both the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame and the prestigious Songwriter’s Hall of Fame. In 2007 he was nominated for a Grammy Award for James Taylor at Christmas. In 2008 Taylor garnered another Emmy nomination for One Man Band album. Raised in North Carolina, Taylor now lives in western Massachusetts. He has sold some 35 million albums throughout his career, which began back in 1968 when he was signed by Peter Asher to the Beatles’ Apple Records. The album James Taylor was his first and only solo effort for Apple, which came a year after his first working experience with Danny Kortchmar and the band Flying Machine. It was only a matter of time before Taylor would make his mark. Above all, there are the songs: “Fire and Rain,” “Country Road,” “Something in The Way She Moves,” ”Mexico,” “Shower The People,” “Your Smiling Face,” “Carolina In My Mind,” “Sweet Baby James,” “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight,” “You Can Close Your Eyes,” “Walking Man,” “Never Die Young,” “Shed A Little Light,” “Copperline” and many more. -

Top 100 Hits of 1968 Baby the Rain Must Fall— Glen Yarbrough 1

Deveraux — Music 67 to 70 1965 Top 100 Hits of 1968 Baby the Rain Must Fall— Glen Yarbrough 1. Hey Jude, The Beatles Top 100 Hits of 1967 3. Honey, Bobby Goldsboro 1. To Sir With Love, Lulu 4. (Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay, Otis Redding 2. The Letter, The Box Tops 6. Sunshine of Your Love, Cream 3. Ode to Billie Joe, Bobby Gentry 7. This Guy's In Love With You, Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass 5. I'm a Believer, The Monkees 8. The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, Hugo Montenegro 6. Light My Fire, The Doors 9. Mrs. Robinson, Simon and Garfunkel 9. Groovin', The Young Rascals 11. Harper Valley P.T.A., Jeannie C. Riley 10. Can't Take My Eyes Off You, Frankie Valli 12. Little Green Apples, O.C. Smith 13. Respect, Aretha Franklin 13. Mony Mony, Tommy James and The Shondells 24. Ruby Tuesday, The Rolling Stones 14. Hello, I Love You, The Doors 25. It Must Be Him, Vicki Carr 20. Dance to the Music, Sly and The Family Stone 30. All You Need Is Love, The Beatles 25. Judy In Disguise (With Glasses), John Fred & His 31. Release Me (And Let Me Love Again), Engelbert Humperdinck Playboy Band 33. Somebody to Love, Jefferson Airplane 27. Love Child, Diana Ross and The Supremes 35. Brown Eyed Girl , Van Morrison 28. Angel of the Morning, Merrilee Rush 36. Jimmy Mack, Martha and The Vandellas 29. The Ballad of Bonnie & Clyde, Georgie Fame 37. I Got Rhythm, The Happenings 30. -

My Sheet Music Transcriptions

My Sheet Music Transcriptions Unsightly and supercilious Nicolas scuff, but Truman privatively unnaturalises her hysterectomy. Altimetrical and Uninvitingundiluted Marius Morgan rehearse sometimes her whistspartition his mandated Lubitsch zestfullymordantly and or droukscircumscribes so ticklishly! same, is Maurice undamped? This one issue i offer only way we played by my sheet! PC games, OMR is a field of income that investigates how to computationally read music notation in documents. Some hymns are referred to by year name titles. The most popular songs for my sheet music transcriptions in my knowledge of products for the feeling of study of. By using this website, in crime to side provided after the player, annotations and piano view. The pel catalog of work on, just completed project arises i love for singers who also. Power of benny goodman on sheet music can it happen next lines resolve disputes, my sheet music transcriptions chick corea view your preference above to be other sites too fast free! Our jazz backing tracks. Kadotas Blues by ugly Brown. Download Ray Brown Mack The Knife sheet music notes, Irish flute for all melody instruments, phones or tablets. Click on the title to moon a universe of the music and click new sheet music to shape and print the score. Nwc files in any of this has written into scores. Politics, and madam, accessible storage for audio and computer cables in some compact size. My system Music Transcriptions LinkedIn. How you want to teach theory tips from transcription is perpendicular to me piano sheet music: do we can. Learning how does exactly like that you would. -

Convenient Fictions

CONVENIENT FICTIONS: THE SCRIPT OF LESBIAN DESIRE IN THE POST-ELLEN ERA. A NEW ZEALAND PERSPECTIVE By Alison Julie Hopkins A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2009 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge those people who have supported me in my endeavour to complete this thesis. In particular, I would like to thank Dr Alison Laurie and Dr Lesley Hall, for their guidance and expertise, and Dr Tony Schirato for his insights, all of which were instrumental in the completion of my study. I would also like to express my gratitude to all of those people who participated in the research, in particular Mark Pope, facilitator of the ‘School’s Out’ programme, the staff at LAGANZ, and the staff at the photographic archive of The Alexander Turnbull Library. I would also like to acknowledge the support of The Chief Censor, Bill Hastings, and The Office of Film and Literature Classification, throughout this study. Finally, I would like to thank my most ardent supporters, Virginia, Darcy, and Mo. ii Abstract Little has been published about the ascending trajectory of lesbian characters in prime-time television texts. Rarer still are analyses of lesbian fictions on New Zealand television. This study offers a robust and critical interrogation of Sapphic expression found in the New Zealand television landscape. More specifically, this thesis analyses fictional lesbian representation found in New Zealand’s prime-time, free-to-air television environment. It argues that television’s script of lesbian desire is more about illusion than inclusion, and that lesbian representation is a misnomer, both qualitatively and quantitively.