Chess Play Icons and the Staunton Chess Set Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FM ALISA MELEKHINA Is Currently Balancing Her Law and Chess Careers. Inside, She Interviews Three Other Lifelong Chess Players Wrestling with a Similar Dilemma

NAKAMURA WINS GIBRALTAR / SO FINISHES SECOND AT TATA STEEL APRIL 2015 Career Crossroads FM ALISA MELEKHINA is currently balancing her law and chess careers. Inside, she interviews three other lifelong chess players wrestling with a similar dilemma. IFC_Layout 1 3/11/2015 6:02 PM Page 1 OIFC_pg1_Layout 1 3/11/2015 7:11 PM Page 1 World’s biggest open tournament! 43rd annual WORLD OPEN Hyatt Regency Crystal City, near D.C. 9rounds,June30-July5,July1-5,2-5or3-5 $210,000 Guaranteed Prizes! Master class prizes raised by $10,000 GM & IM norms possible, mixed doubles prizes, GM lectures & analysis! VISIT OUR NATION’S CAPITAL SPECIAL FEATURES! 4) Provisional (under 26 games) prize The World Open completes a three 1) Schedule options. 5-day is most limits in U2000 & below. year run in the Washington area before popular, 4-day and 3-day save time & 5) Unrated not allowed in U1200 returning to Philadelphia in 2016. money.New,leisurely6-dayhas three1- though U1800;$1000 limit in U2000. $99 rooms, valet parking $6 (if full, round days. Open plays 5-day only. 6) Mixed Doubles: $3000-1500-700- about $7-15 nearby), free airport shuttle. 2) GM & IM norms possible in Open. 500-300 for male/female teams. Fr e e s hutt l e to DC Metro, minutes NOTECHANGE:Mas ters can now play for 7) International 6/26-30: FIDE norms from Washington’s historic attractions! both norms & large class prizes! possible, warm up for main event. Als o 8sections:Open,U2200,U2000, 3) Prize limit $2000 if post-event manyside events. -

How to Setup Chess Board - Easy

How to setup Chess Board - Easy By G Bud Games https://gbud.in July 24, 2021 Contents 1 How to setup Chess Board - Easy 3 1.1 Squares in chess board .................... 3 1.2 Ranks and files of chess board ................ 8 1.2.1 Rank in chess ..................... 8 1.2.2 File in Chess ..................... 10 1.3 Piece arrangement ...................... 12 1.4 Colors of chess pieces ..................... 12 1.5 Initial setup of chess board .................. 12 1.6 Staunton chess set ...................... 17 1 List of Figures 1.1 Squares in a chess board ................... 4 1.2 Column names at chess board ................ 4 1.3 Row numbers at at chess board ............... 5 1.4 Names of Chess squares ................... 5 1.5 Default position of white king at chess board ........ 6 1.6 Default position of black queen at chess board ....... 6 1.7 a1 square at chess board ................... 7 1.8 h8 square at chess board ................... 7 1.9 Rank in a chess board .................... 8 1.10 Rank 1 in a chess board ................... 9 1.11 Rank 8 in a chess board ................... 9 1.12 File in a chess board ..................... 10 1.13 A file in a chess board .................... 11 1.14 H file in a chess board .................... 11 1.15 Height of chess pieces ..................... 12 1.16 Initial setup of chess board .................. 13 1.17 Queen’s position at chess board ............... 14 1.18 King’s position at chess board ................ 14 1.19 Knight’s position at chess board ............... 15 1.20 Rook’s position at chess board ................ 15 1.21 Bishop’s position at chess board .............. -

Yugoslavia Staunton Chess Set in Ebony & Boxwood with Mission

Read the "Yugoslavia Staunton Chess Set in Ebony & Boxwood with Mission Craft African Padauk Chess Board - 3.875\" King" for your favorite. Here you will find reasonable how to and details many special offers. This chess set package includes our Yugoslavia Staunton Chess Set in ebony and boxwood matched with our Mission Craft African Padauk and Maple Solid Wood Chess Board. The polished black ebony pieces create a beautiful contrast with the red colors of the African padauk - they look stunning together! Our Yugoslavia Staunton originates from the chess set designed for the 1950 Chess Olympiad held in Dubrovnik,Yugoslavia. This unique and handsome Staunton design has since become a favorite for chess players around the world and one of our most popular chess sets. We made a few minor changes such as adding a tapered base to enhance appearance and balance of the chess pieces while maintaining the integrity of the intended design. You\'ll love playing with this chess set whether it\'s a casual game at home or a tournament match. The king is 3.875\" tall with a 1.625\" wide base and features a traditional formee cross. The pieces are triple-weighted to produce a low-center of gravity and exceptional stability on the chess board. The pieces are padded with thick green baize for a nice cushion when picking up and moving or sliding across the chess board. The pieces are individually hand polished to beautiful luster. Our African Padauk and Maple Mission Craft Solid Wood Chess Board is simplistically beautiful and profoundly designed. -

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (Later, in Europe, Replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS from the DR

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (later, in Europe, replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE DR. queen). These were typically flanKed GEORGE AND VIVIAN DEAN by elephants (later to become COLLECTION bishops), though in this case, they are EXHIBITION CHECKLIST camels with drummers; cavalrymen (later to become Knights); and World Chess Hall of Fame chariots or elephants, (later to Saint Louis, Missouri 2.1. Abstract Bead anD Dart Style Set become rooKs or “castles”). A September 9, 2011-February 12, with BoarD, India, 1700s. Natural and frontline of eight foot soldiers 2012 green-stained ivory, blacK lacquer- (pawns) completed each side. work folding board with silver and mother-of-pearl. This classical Indian style is influenced by the Islamic trend toward total abstraction of the design. The pieces are all lathe- turned. The blacK lacquer finish, made in India from the husKs of the 1.1. Neresheimer French vs. lac insect, was first developed by the Germans Set anD Castle BoarD, Chinese. The intricate inlaid silver Hanau, Germany, 1905-10. Silver and grid pattern traces alternating gilded silver, ivory, diamonds, squares filled with lacy inscribed fern sapphires, pearls, amethysts, rubies, leaf designs and inlaid mother-of- and marble. pearl disKs. These decorations 2.3. Mogul Style Set with combine a grid of squares, common Presentation Case, India, 1800s. Before WWI, Neresheimer, of Hanau, to Western forms of chess, with Beryl with inset diamonds, rubies, Germany, was a leading producer of another grid of inlaid center points, and gold, wooden presentation case ornate silverware and decorative found in Japanese and Chinese clad in maroon velvet and silk-lined. -

Chess & Bridge

2013 Catalogue Chess & Bridge Plus Backgammon Poker and other traditional games cbcat2013_p02_contents_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:18 Page 1 Contents CONTENTS WAYS TO ORDER Chess Section Call our Order Line 3-9 Wooden Chess Sets 10-11 Wooden Chess Boards 020 7288 1305 or 12 Chess Boxes 13 Chess Tables 020 7486 7015 14-17 Wooden Chess Combinations 9.30am-6pm Monday - Saturday 18 Miscellaneous Sets 11am - 5pm Sundays 19 Decorative & Themed Chess Sets 20-21 Travel Sets 22 Giant Chess Sets Shop online 23-25 Chess Clocks www.chess.co.uk/shop 26-28 Plastic Chess Sets & Combinations or 29 Demonstration Chess Boards www.bridgeshop.com 30-31 Stationery, Medals & Trophies 32 Chess T-Shirts 33-37 Chess DVDs Post the order form to: 38-39 Chess Software: Playing Programs 40 Chess Software: ChessBase 12` Chess & Bridge 41-43 Chess Software: Fritz Media System 44 Baker Street 44-45 Chess Software: from Chess Assistant 46 Recommendations for Junior Players London, W1U 7RT 47 Subscribe to Chess Magazine 48-49 Order Form 50 Subscribe to BRIDGE Magazine REASONS TO SHOP ONLINE 51 Recommendations for Junior Players - New items added each and every week 52-55 Chess Computers - Many more items online 56-60 Bargain Chess Books 61-66 Chess Books - Larger and alternative images for most items - Full descriptions of each item Bridge Section - Exclusive website offers on selected items 68 Bridge Tables & Cloths 69-70 Bridge Equipment - Pay securely via Debit/Credit Card or PayPal 71-72 Bridge Software: Playing Programs 73 Bridge Software: Instructional 74-77 Decorative Playing Cards 78-83 Gift Ideas & Bridge DVDs 84-86 Bargain Bridge Books 87 Recommended Bridge Books 88-89 Bridge Books by Subject 90-91 Backgammon 92 Go 93 Poker 94 Other Games 95 Website Information 96 Retail shop information page 2 TO ORDER 020 7288 1305 or 020 7486 7015 cbcat2013_p03to5_woodsets_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:53 Page 1 Wooden Chess Sets A LITTLE MORE INFORMATION ABOUT OUR CHESS SETS.. -

The Queen's Gambit

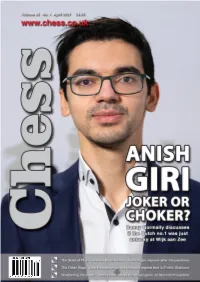

01-01 Cover - April 2021_Layout 1 16/03/2021 13:03 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/03/2021 11:45 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Associate Editor: John Saunders 60 Seconds with...Geert van der Velde.....................................................7 Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington We catch up with the Play Magnus Group’s VP of Content Chess Magazine (ISSN 0964-6221) is published by: A Tale of Two Players.........................................................................................8 Chess & Bridge Ltd, 44 Baker St, London, W1U 7RT Wesley So shone while Carlsen struggled at the Opera Euro Rapid Tel: 020 7486 7015 Anish Giri: Choker or Joker?........................................................................14 Email: [email protected], Website: www.chess.co.uk Danny Gormally discusses if the Dutch no.1 was just unlucky at Wijk Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Daniel King also takes a look at the play of Anish Giri Twitter: @chessandbridge The Other Saga ..................................................................................................22 Subscription Rates: John Henderson very much -

The English School of Chess: a Nation on Display, 1834-1904

Durham E-Theses The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 HARRISON, EDWARD,GRAHAM How to cite: HARRISON, EDWARD,GRAHAM (2018) The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12703/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 Edward Harrison This thesis is submitted for the degree of MA by Research in the department of History at Durham University March 2018 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the author's prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. -

Rules of Chess

Rules of chess From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The rules of chess (also known as the laws of chess) are rules governing the play of the game of chess. While the exact origins of chess are unclear, modern rules first took form during the Middle Ages. The rules continued to be slightly modified until the early 19th century, when they reached essentially their current form. The rules also varied somewhat from place to place. Today Fédération Internationale des Échecs (FIDE), also known as the World Chess Organization, sets the standard rules, with slight modifications made by some national organizations for their own purposes. There are variations of the rules for fast chess, correspondence chess, online chess, and chess variants. Chess is a game played by two people on a chessboard, with 32 pieces (16 for each player) of six types. Each type of piece moves in a distinct way. The goal of the game is to checkmate, i.e. to threaten the opponent's king with inevitable capture. Games do not necessarily end with checkmate – players often resign if they believe they will lose. In addition, there are several ways that a game can end in a draw. Besides the basic movement of the pieces, rules also govern the equipment used, the time control, the conduct and ethics of players, accommodations for handicapped players, the recording of moves using chess notation, as well as procedures for irregularities that occur during a game. Contents 1 Initial setup 1.1 Identifying squares 2 Play of the game 2.1 Movement 2.1.1 Basic moves 2.1.2 Castling 2.1.3 En passant 2.1.4 Pawn promotion Game in a public park in Kiev, using a 2.2 Check chess clock 3 End of the game 3.1 Checkmate 3.2 Resigning 3.3 Draws 3.4 Time control 4 Competition rules 4.1 Act of moving the pieces 4.2 Touch-move rule 4.3 Timing 4.4 Recording moves 4.5 Adjournment 5 Irregularities 5.1 Illegal move 5.2 Illegal position 6 Conduct Staunton style chess pieces. -

Download the Latest Catalogue

TABLE OF CONTENTS To view a particular category within the catalogue please click on the headings below 1. Antiquarian 2. Reference; Encyclopaedias, & History 3. Tournaments 4. Game collections of specific players 5. Game Collections – General 6. Endings 7. Problems, Studies & “Puzzles” 8. Instructional 9. Magazines & Yearbooks 10. Chess-based literature 11. Children & Junior Beginners 12. Openings Keverel Chess Books July – January. Terms & Abbreviations The condition of a book is estimated on the following scale. Each letter can be finessed by a + or - giving 12 possible levels. The judgement will be subjective, of course, but based on decades of experience. F = Fine or nearly new // VG = very good // G = showing acceptable signs of wear. P = Poor, structural damage (loose covers, torn pages, heavy marginalia etc.) but still providing much of interest. AN = Algebraic Notation in which, from White’s point of view, columns are called a – h and ranks are numbered 1-8 (as opposed to the old descriptive system). Figurine, in which piece names are replaced by pictograms, is now almost universal in modern books as it overcomes the language problem. In this case AN may be assumed. pp = number of pages in the book.// ed = edition // insc = inscription – e.g. a previous owner’s name on the front endpaper. o/w = otherwise. dw = Dust wrapper It may be assumed that any book published in Russia will be in the Russian language, (Cyrillic) or an Argentinian book will be in Spanish etc. Anything contrary to that will be mentioned. PB = paperback. SB = softback i.e. a flexible cover that cannot be torn easily. -

Chess Sets from 1700 to the Introduction of the Staunton Design (1849)

Page 1 of 7 The Conventional Chess Sets from 1700 to the introduction of the Staunton Design (1849) Chesmayne Chess History Time Lines: 1500's . 1600's . 1700's . 1800's . 1900's Today, the Staunton design, named after a Chess Master in England, but actually developed by and produced by John Jaques of London in 1849, is now the standard design for chess pieces. Prior to that, a number of Conventional styles of turned chess sets preceded the introduction of the Staunton Design in 1849. These pieces were designed for play using simplified or abstract shapes and made of more inexpensive materials than more ornate displays sets. Some of these various styles were named after either the Coffee House/ Chess Clubs in London and Paris, and other European cities where they were used; or the skilled turners who created them. Along with these Conventional Playing Sets, there were also a variety of Representational Sets - the latter tended to be more for display than play. The original chess sets from the East were highly abstracted pieces. Early Western sets were carved figures such as the Lewis Chess men or those of Charlemagne's time. In the Middle Ages, Chess was a game mainly for the Nobility and Clergy. They could afford expensive ornate sets. During the Renaissance, it was still mainly a game for the households of kings such as Philip II of Spain or Henry the 8th; and the Queens, such as Catherine De Medici, or Elizabeth I. A revolution in Chess play in the West was the development of the powerful Chess Queen. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

Staunton Chess Set - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos

Staunton Chess Set - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos Staunton Chess Set Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos [email protected] Culture is the social use of human intelligence Gabriel García Márquez Contents: Introduction. 1. ORIGIN OF STAUNTON CHESS SET. 1.1. Novelty of the Registered Design. 1.2. Authorship and Place of Origin. 1.3. Importance of the Name. 1.4. Signature Guarantee. 2. OFFICIAL PIECES. 3. INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE. 3.1. Concept. 3.2. Reality and Formality. 3.3. Potential Advantages. 4. CHARACTERISTICS OF STAUNTON CHESS SET 4.1. Form and Function. 4.2. Special Features. 5. CURRENT SITUATION. Appendix: Brief list of major museums, private collections, and shops in Internet Classic Staunton Chess Set INTRODUCTION. As surprising as this may seem, not all the chess sets have been designed to play, hence, we find: 1 Staunton Chess Set - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos - Functional pieces, designed to play, and - Ornamental pieces, designed to decorate (1) This article focuses on the best known functional pieces, called Staunton, which are widely accepted by casual and professionals players around the world. The Staunton chessmen were created in London in 1849, during the Victorian Era, over 160 years ago. They are masterpieces of functionality and elegance, so they have become the unique and unmistakable classic chess game pieces. Many players cannot imagine the game with other pieces. In 1924, these pieces were selected as the official set by the World Chess Federation; presently, for about 600 million players in over 120 countries, Stauton pieces are the choice of set.