Design of the Staunton Chess Set

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bishop and Knight Save the Day: a World Champion's Favorite Studies

Bishop and Knight Save the Day: A World Champion’s Favorite Studies Sergei Tkachenko Bishop and Knight Save the Day: A World Champion’s Favorite Studies Author: Sergei Tkachenko Translated from the Russian by Ilan Rubin Chess editor: Anastasia Travkina Typesetting by Andrei Elkov (www.elkov.ru) © LLC Elk and Ruby Publishing House, 2019. All rights reserved Cover page drawing by Anna Fokina Illustration Studio (www.fox-artwork.com) Follow us on Twitter: @ilan_ruby www.elkandruby.com ISBN 978-5-6040710-9-0 2 THE BISHOP AND THE KNIGHT HAND IN HAND… The bishop and knight pair often make chess players shudder. Why? Because of the tricky checkmate! Mating with a bishop and knight is far from simple. Indeed, there have been cases when famous players were unable to mate their opponent in the allocated 50 moves. One example involved the Kievan master Evsey Poliak. The game ended in a draw after he failed to mate his opponent with bishop, knight and king versus a lone king. After the game, somebody asked him why he didn’t chase the enemy king into a corner that was the same color as his bishop. The disappointed Poliak replied: “I kept trying to chase him but for some reason the king refused to move there!” There was even an old painting that captured this balance of forces! Back in 1793, French artist Remi-Fursy Descarsin painted a doctor playing chess against… the Grim Reaper, no less. And the doctor looks dead pleased, because he’s just mated Death himself with a bishop and knight! 3 Here’s that position from Descarsin’s painting (No. -

FM ALISA MELEKHINA Is Currently Balancing Her Law and Chess Careers. Inside, She Interviews Three Other Lifelong Chess Players Wrestling with a Similar Dilemma

NAKAMURA WINS GIBRALTAR / SO FINISHES SECOND AT TATA STEEL APRIL 2015 Career Crossroads FM ALISA MELEKHINA is currently balancing her law and chess careers. Inside, she interviews three other lifelong chess players wrestling with a similar dilemma. IFC_Layout 1 3/11/2015 6:02 PM Page 1 OIFC_pg1_Layout 1 3/11/2015 7:11 PM Page 1 World’s biggest open tournament! 43rd annual WORLD OPEN Hyatt Regency Crystal City, near D.C. 9rounds,June30-July5,July1-5,2-5or3-5 $210,000 Guaranteed Prizes! Master class prizes raised by $10,000 GM & IM norms possible, mixed doubles prizes, GM lectures & analysis! VISIT OUR NATION’S CAPITAL SPECIAL FEATURES! 4) Provisional (under 26 games) prize The World Open completes a three 1) Schedule options. 5-day is most limits in U2000 & below. year run in the Washington area before popular, 4-day and 3-day save time & 5) Unrated not allowed in U1200 returning to Philadelphia in 2016. money.New,leisurely6-dayhas three1- though U1800;$1000 limit in U2000. $99 rooms, valet parking $6 (if full, round days. Open plays 5-day only. 6) Mixed Doubles: $3000-1500-700- about $7-15 nearby), free airport shuttle. 2) GM & IM norms possible in Open. 500-300 for male/female teams. Fr e e s hutt l e to DC Metro, minutes NOTECHANGE:Mas ters can now play for 7) International 6/26-30: FIDE norms from Washington’s historic attractions! both norms & large class prizes! possible, warm up for main event. Als o 8sections:Open,U2200,U2000, 3) Prize limit $2000 if post-event manyside events. -

UIL Text 111212

UIL Chess Puzzle Solvin g— Fall/Winter District 2016-2017 —Grades 4 and 5 IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS: [Test-administrators, please read text in this box aloud.] This is the UIL Chess Puzzle Solving Fall/Winter District Test for grades four and five. There are 20 questions on this test. You have 30 minutes to complete it. All questions are multiple choice. Use the answer sheet to mark your answers. Multiple choice answers pur - posely do not indicate check, checkmate, or e.p. symbols. You will be awarded one point for each correct answer. No deductions will be made for incorrect answers on this test. Finishing early is not rewarded, even to break ties. So use all of your time. Some of the questions may be hard, but all of the puzzles are interesting! Good luck and have fun! If you don’t already know chess notation, reading and referring to the section below on this page will help you. How to read and answer questions on this test Piece Names Each chessman can • To answer the questions on this test, you’ll also be represented need to know how to read chess moves. It’s by a symbol, except for the pawn. simple to do. (Figurine Notation) K King Q • Every square on the board has an “address” Queen R made up of a letter and a number. Rook B Bishop N Knight Pawn a-h (We write the file it’s on.) • To make them easy to read, the questions on this test use the figurine piece symbols on the right, above. -

More About Checkmate

MORE ABOUT CHECKMATE The Queen is the best piece of all for getting checkmate because it is so powerful and controls so many squares on the board. There are very many ways of getting CHECKMATE with a Queen. Let's have a look at some of them, and also some STALEMATE positions you must learn to avoid. You've already seen how a Rook can get CHECKMATE XABCDEFGHY with the help of a King. Put the Black King on the side of the 8-+k+-wQ-+( 7+-+-+-+-' board, the White King two squares away towards the 6-+K+-+-+& middle, and a Rook or a Queen on any safe square on the 5+-+-+-+-% same side of the board as the King will give CHECKMATE. 4-+-+-+-+$ In the first diagram the White Queen checks the Black King 3+-+-+-+-# while the White King, two squares away, stops the Black 2-+-+-+-+" King from escaping to b7, c7 or d7. If you move the Black 1+-+-+-+-! King to d8 it's still CHECKMATE: the Queen stops the Black xabcdefghy King moving to e7. But if you move the Black King to b8 is CHECKMATE! that CHECKMATE? No: the King can escape to a7. We call this sort of CHECKMATE the GUILLOTINE. The Queen comes down like a knife to chop off the Black King's head. But there's another sort of CHECKMATE that you can ABCDEFGH do with a King and Queen. We call this one the KISS OF 8-+k+-+-+( DEATH. Put the Black King on the side of the board, 7+-wQ-+-+-' the White Queen on the next square towards the middle 6-+K+-+-+& and the White King where it defends the Queen and you 5+-+-+-+-% 4-+-+-+-+$ get something like our next diagram. -

How to Setup Chess Board - Easy

How to setup Chess Board - Easy By G Bud Games https://gbud.in July 24, 2021 Contents 1 How to setup Chess Board - Easy 3 1.1 Squares in chess board .................... 3 1.2 Ranks and files of chess board ................ 8 1.2.1 Rank in chess ..................... 8 1.2.2 File in Chess ..................... 10 1.3 Piece arrangement ...................... 12 1.4 Colors of chess pieces ..................... 12 1.5 Initial setup of chess board .................. 12 1.6 Staunton chess set ...................... 17 1 List of Figures 1.1 Squares in a chess board ................... 4 1.2 Column names at chess board ................ 4 1.3 Row numbers at at chess board ............... 5 1.4 Names of Chess squares ................... 5 1.5 Default position of white king at chess board ........ 6 1.6 Default position of black queen at chess board ....... 6 1.7 a1 square at chess board ................... 7 1.8 h8 square at chess board ................... 7 1.9 Rank in a chess board .................... 8 1.10 Rank 1 in a chess board ................... 9 1.11 Rank 8 in a chess board ................... 9 1.12 File in a chess board ..................... 10 1.13 A file in a chess board .................... 11 1.14 H file in a chess board .................... 11 1.15 Height of chess pieces ..................... 12 1.16 Initial setup of chess board .................. 13 1.17 Queen’s position at chess board ............... 14 1.18 King’s position at chess board ................ 14 1.19 Knight’s position at chess board ............... 15 1.20 Rook’s position at chess board ................ 15 1.21 Bishop’s position at chess board .............. -

The Fianchetto Solution: a Complete, Solid and Flexible Chess Opening Repertoire for Black White - with the King's Fianchetto (New in Chess) Online

iqo7p [Read and download] The Fianchetto Solution: A Complete, Solid and Flexible Chess Opening Repertoire for Black White - with the King's Fianchetto (New in Chess) Online [iqo7p.ebook] The Fianchetto Solution: A Complete, Solid and Flexible Chess Opening Repertoire for Black White - with the King's Fianchetto (New in Chess) Pdf Free Emmanuel Neiman, Samy Shoker *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #465530 in Books The House of Staunton, Inc. 2016-12-15Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.19 x .61 x 6.72l, .0 #File Name: 9056916637272 pagesAuthor: Emmanuel Neiman,Samy ShokerPages: 272 PagesPublication Years: 2016 | File size: 39.Mb Emmanuel Neiman, Samy Shoker : The Fianchetto Solution: A Complete, Solid and Flexible Chess Opening Repertoire for Black White - with the King's Fianchetto (New in Chess) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Fianchetto Solution: A Complete, Solid and Flexible Chess Opening Repertoire for Black White - with the King's Fianchetto (New in Chess): 4 of 4 people found the following review helpful. How to Handle Fianchetto BishopsBy Danny WoodallBook gives you plans on how to handle positions with a fianchetto bishop. Good games with good explanations. Anyone playing fianchetto positions can learn from this book.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. A good book on a not so common chess subject.By CustomerIf you read and study this book, and then decide that you may not actually be comfortable with this opening, your time, I suggest, would not have been wasted.On the other hand, I would encourage all chess students to give this opening, at least, an occasional try.Reading and studying this book for me was time well spent (My ELO is +2000).The title of this book could also be called "A Deep Introduction to Fianchetto Positions." Most chess student, who are deficient in their knowledge on this topic, would find this book's study to be of benefit. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”. -

Yugoslavia Staunton Chess Set in Ebony & Boxwood with Mission

Read the "Yugoslavia Staunton Chess Set in Ebony & Boxwood with Mission Craft African Padauk Chess Board - 3.875\" King" for your favorite. Here you will find reasonable how to and details many special offers. This chess set package includes our Yugoslavia Staunton Chess Set in ebony and boxwood matched with our Mission Craft African Padauk and Maple Solid Wood Chess Board. The polished black ebony pieces create a beautiful contrast with the red colors of the African padauk - they look stunning together! Our Yugoslavia Staunton originates from the chess set designed for the 1950 Chess Olympiad held in Dubrovnik,Yugoslavia. This unique and handsome Staunton design has since become a favorite for chess players around the world and one of our most popular chess sets. We made a few minor changes such as adding a tapered base to enhance appearance and balance of the chess pieces while maintaining the integrity of the intended design. You\'ll love playing with this chess set whether it\'s a casual game at home or a tournament match. The king is 3.875\" tall with a 1.625\" wide base and features a traditional formee cross. The pieces are triple-weighted to produce a low-center of gravity and exceptional stability on the chess board. The pieces are padded with thick green baize for a nice cushion when picking up and moving or sliding across the chess board. The pieces are individually hand polished to beautiful luster. Our African Padauk and Maple Mission Craft Solid Wood Chess Board is simplistically beautiful and profoundly designed. -

NEW HAMPSHIRE CHESS JOURNAL Is a Publication of the New Hampshire Chess Association

New Hampshire Chess Journal December 2013 Volume 2013 No. 1 Return of the King: Sharif Khater Story, Page 2 Khater Returns as 2013 NH Amateur Champ Manchester--Sherif Khater recaptured the State Amateur crown, which he first held in 2010, by beating Arthur Tang in the final round of the 38th New Hampshire Amateur Championship, held at the Comfort Inn in Manchester on November 2. Only a second round draw with Brian Bambrough blemished Khater’s score. Four tied for second place: Gerald Potorski, Jefferey Ames, Clay Bradley, and Joshua Cote. John Jay Naylor won the Intermediate section with a perfect 4.0 score. Thomas Allen of Maine scored a perfect 4.0 for first place in the Novice section. Sixty-four players competed in the four round, one day event. Hal Terrie directed with the assistance of John Elmore. The crosstable can be viewed here. Bournival NH Open State Champ Manchester—Brad Bournival was named the 2013 NH State Champion at the 63rd New Hampshire Open. GM Alexander Ivanov and Jonathan Yedidia, both of Massachusetts, shared first place. Yedidia caught Ivanov in the final round by beating Brian Salomon while Ivanov drew with state champ Brad Bournival, leaving the leaders with 4.0 points each. Bournival took third place. John Pythyon, Sr. of Maine won the under 1950 section, while Paul Kolojeski Alexander Ivanov and Brian Salomon square off in Round 4. Ivanov won. 2 prevailed in the Under 1650 section. The Open drew 37 participants to the Manchester Comfort in on June 14-16. The tournament was directed by Hal Terrie with John Elmore assisting. -

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (Later, in Europe, Replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS from the DR

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (later, in Europe, replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE DR. queen). These were typically flanKed GEORGE AND VIVIAN DEAN by elephants (later to become COLLECTION bishops), though in this case, they are EXHIBITION CHECKLIST camels with drummers; cavalrymen (later to become Knights); and World Chess Hall of Fame chariots or elephants, (later to Saint Louis, Missouri 2.1. Abstract Bead anD Dart Style Set become rooKs or “castles”). A September 9, 2011-February 12, with BoarD, India, 1700s. Natural and frontline of eight foot soldiers 2012 green-stained ivory, blacK lacquer- (pawns) completed each side. work folding board with silver and mother-of-pearl. This classical Indian style is influenced by the Islamic trend toward total abstraction of the design. The pieces are all lathe- turned. The blacK lacquer finish, made in India from the husKs of the 1.1. Neresheimer French vs. lac insect, was first developed by the Germans Set anD Castle BoarD, Chinese. The intricate inlaid silver Hanau, Germany, 1905-10. Silver and grid pattern traces alternating gilded silver, ivory, diamonds, squares filled with lacy inscribed fern sapphires, pearls, amethysts, rubies, leaf designs and inlaid mother-of- and marble. pearl disKs. These decorations 2.3. Mogul Style Set with combine a grid of squares, common Presentation Case, India, 1800s. Before WWI, Neresheimer, of Hanau, to Western forms of chess, with Beryl with inset diamonds, rubies, Germany, was a leading producer of another grid of inlaid center points, and gold, wooden presentation case ornate silverware and decorative found in Japanese and Chinese clad in maroon velvet and silk-lined. -

Chess Rules Ages 10 & up • for 2 Players

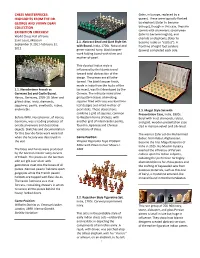

Front (Head to Head) Prints Pantone 541 Blue Chess Rules Ages 10 & Up • For 2 Players Contents: Game Board, 16 ivory and 16 black Play Pieces Object: To threaten your opponent’s King so it cannot escape. Play Pieces: Set Up: Ivory Play Pieces: Black Play Pieces: Pawn Knight Bishop Rook Queen King Terms: Ranks are the rows of squares that run horizontally on the Game Board and Files are the columns that run vertically. Diagonals run diagonally. Position the Game Board so that the red square is at the bottom right corner for each player. Place the Ivory Play Pieces on the first rank from left to right in order: Rook, Knight, Bishop, Queen, King, Bishop, Knight and Rook. Place all of the Pawns on the second rank. Then place the Black Play Pieces on the board as shown in the diagram. Note: the Ivory Queen will be on a red square and the black Queen will be on a black space. Play: Ivory always plays first. Players alternate turns. Only one Play Piece may be moved on a turn, except when castling (see description on back). All Play Pieces must move in a straight path, except for the Knight. Also, the Knight is the only Play Piece that is allowed to jump over another Play Piece. Play Piece Moves: A Pawn moves forward one square at a time. There are two exceptions to this rule: 1. On a Pawn’s first move, it can move forward one or two squares. 2. When capturing a piece (see description on back), a Pawn moves one square diagonally ahead.