Annapurna Pandey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In a New and Calm Nepal, the Famed Annapurna Circuit May Soon

LAST RIDE ON THE ANNAPURNA In a new and calm Nepal, the famed Annapurna stone, cold and beautiful. We hang our We’re riding the Annapurna Circuit, prayer flags with the others — symbols of a famous trekking route circling the Circuit may soon become the most incredible desires, dreams, wishes. Then we point our Annapurna Massif in Nepal. It’s normally a mountain-bike touring route in the Himalayas — front wheels downhill. tough 18-day hike that starts in the jungles but at what cost? Nathan Ward rides the fine line And it’s a long downhill, sharp and tech- of the middle hills of Nepal, climbs toward nical, and we ride it all with the befuddled the Tibetan plateau, crosses the high between tradition, legend, and change. brain waves of thin air – jolting through Thorung La, and plummets back to the boulder gardens, slicing into snowdrifts, jungles again. Even though it’s currently t 4:30 a.m., 16,000 feet high in the the sun, the alpine world unfolds before us rolling along perfect sections of singletrack, better suited for feet, we’ve decided to ride Himalayas, the stars shimmer blue in magically like an icy bouquet of high peaks A or just holding on and praying through sec- it on bikes — me, my wife Andrea, and our the cold alpine air. Moon-glow bounces from fanned out across the horizon. We get tions so steep they’re more of a controlled fearless local guide Chandra — to explore a glaciers, wavering, otherworldly, ghostly. on our bikes and pedal shakily up the last slide than a ride. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

The Voice of Feminism in Odia Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue1 Ser. II || Jan, 2020 || PP 01-04 The Voice of Feminism in Odia Literature Dr. Ajay Kumar Panda Sr. Lecturer in Odia Upendranath College, Soro, Balasore, Odisha ABSTRACT : Feminism, in literature as well as otherwise, began as an expression of dissatisfaction regarding the attitude of the society towards the identity and rights of women. However, slowly, it evolved to empower women to make her financially, socially and psychologically independent. In the field of literature, it evolved to finally enable the female writers to be free from the influence of male writers as well as the social norms that suggested different standards for male and female KEYWORDS – Feminism, identity and rights of women, empower women, free from the influence of male writers ,Sita, Draupadi,Balaram Das, Vaishanbism, Panchasakha, Kuntala Kumari, Rama Devi, Sarala Devi, Nandini Satapathy, Prativa Ray,Pratiova Satapathy, Sarojini Sahu.Ysohodhara Mishra ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ --------------- Date of Submission: 18-01-2020 Date of Acceptance: 06-02-2020 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION: Feminism in Indian literature, as can be most commonly conceived is a much sublime and over-the-top concept, -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

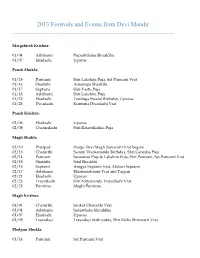

2013 Festivals and Events from Devi Mandir

2013 Festivals and Events from Devi Mandir Margshirsh Krishna: 01/04 Ashthami Pupashthaka Shraddha 01/07 Ekadashi Upavas Paush Shukla: 01/15 Pancami Shri Lakshmi Puja, Sat Pancami Vrat 01/16 Shashthi Annarupa Shashthi 01/17 Saptami Shri Vastu Puja 01/18 Ashthami Shri Lakshmi Puja 01/22 Ekadashi Trailinga Swami Birthday, Upavas 01/23 Dwadashi Kurmma Dwadashi Vrat Paush Krishna: 02/06 Ekadashi Upavas 02/08 Chaturdashi Shri Ratantikalika Puja Magh Shukla: 02/10 Pratipad Durga Devi Magh Navaratri Vrat begins 02/13 Chaturthi Swami Vivekananda Birthday, Shri Ganesha Puja 02/14 Pancami Saraswati Puja & Lakshmi Puja, Shri Pancami, Sat Pancami Vrat 02/15 Shashthi Sital Shashthi 02/16 Saptami Arogya Saptami Vrat, Makari Saptami 02/17 Ashthami Bhishmashtami Vrat and Tarpan 02/21 Ekadashi Upavas 02/23 Trayodashi Shri Nityananda Trayodashi Vrat 02/25 Purnima Maghi Purnima Magh Krishna: 03/01 Chaturthi Sankat Chaturthi Vrat 03/04 Ashthami Sakasthaka Shraddha 03/07 Ekadashi Upavas 03/09 Trayodasi Trayodasi nishi yukta, Shri Maha Shivaratri Vrat Phalgun Shukla: 03/16 Pancami Sat Pancami Vrat 03/17 Shashthi Gorupini Shashthi 03/22 Ekadashi Shri Ramakrishna’s Birthday 03/26 Purnima Shri Krishna Dol Yatra, Holi, Gauranga Mahaprabhu Avirbhav Phalgun Krishna: 03/31 Pancami Shri Krishna Pancama Dol Yatra 04/01 Shashthi Skanda Shashthi 04/03 Ashthami Shri Sitalashtami 04/05 Ekadashi Upavas 04/07 Trayodashi Madhu Krishna Trayodashi Caitra Shukla: 04/10 Pratipad Vasanti Durga Devi Navaratri Vrat 04/15 Pancami Sat Pancami Vrat 04/16 Shashthi Shri Vasanti Durga -

Finding Zen on the Himalayas After a Nightmare Ride to the Top by Munir Virani

Features Munir (left) against the backdrop of the stunning Himalayas Finding Zen on the Himalayas after a nightmare ride to the top By Munir Virani n Hindu mythology, Kali is the Goddess That is what I felt when I rode up the Himalayas and its enormous hydroelectric of Death. In Sanskrit, the translation is Kali Gandaki Valley in Nepal’s Annapurna potential. It has a total catchment area of “She who is black or she who is death”. Conservation Area in May of 2013. The Kali 46,300 square kilometers (17,900sq.mi), IKali’s iconography, cult, and mythology Gandaki River is one of the major rivers most of it in Nepal. This blog is about commonly associate her with death, of Nepal and a left bank tributary of the my journey up the Kali Gandaki from sexuality, violence, and, paradoxically in sacred Ganges in India. In Nepal the river where we began our survey of Himalayan some later traditions, with motherly love. is notable for its deep gorge through the Vultures and other raptors of the region. My last visit to Nepal was in February 2004 when The Peregrine Fund organized a Kathmandu Summit Meeting. The goal of that meeting was to disseminate results of our discovery of veterinary diclofenac as the primary cause of the catastrophic collapse of Gyps vultures in South Asia. Last month, I returned to Nepal after nine years and could not help but feel a tremendous surge of nostalgia when our plane touched down at Kathmandu’s Tribhuvan International Airport. I was overwhelmed by emotion as I had very fond memories of this wonderful Himalayan country. -

The Life of Krishna Chaitanya

The Life of Krishna Chaitanya first volume of the series: The Life and Teachings of Krishna Chaitanya by Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center (second edition) Copyright © 2016 Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center All rights reserved. ISBN-13: 978-1532745232 ISBN-10: 1532745230 Our Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center is a non-profit organization, dedicated to the research, preservation and propagation of Vedic knowledge and tradition, commonly described as “Hinduism”. Our main work consists in publishing and popularizing, translating and commenting the original scriptures and also texts dealing with history, culture and the peoblems to be tackled to re-establish a correct vision of the original Tradition, overcoming sectarianism and partisan political interests. Anyone who wants to cooperate with the Center is welcome. We also offer technical assistance to authors who wish to publish their own works through the Center or independently. For further information please contact: Mataji Parama Karuna Devi [email protected], [email protected] +91 94373 00906 Contents Introduction 11 Chaitanya's forefathers 15 Early period in Navadvipa 19 Nimai Pandita becomes a famous scholar 23 The meeting with Keshava Kashmiri 27 Haridasa arrives in Navadvipa 30 The journey to Gaya 35 Nimai's transformation in divine love 38 The arrival of Nityananda 43 Advaita Acharya endorses Nimai's mission 47 The meaning of Krishna Consciousness 51 The beginning of the Sankirtana movement 54 Nityananda goes begging -

Shakta and Shakti by Usha Chatterji

Shakta and Shakti By Usha Chatterji Source: Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 2, No.4. (Autumn 1968) © World Wisdom, Inc. www.studiesincomparativereligion.com THE cult of the Mother Goddess is as old as humanity. It is believed that in antiquity the cult extended to all the countries and thrived in all the civilizations from the Nile and Euphrates to the Aegean Sea; "Looking to the east of the Euphrates we see the Dusk Divinity of India, the Adya-Shakti and Maha-Shakti, or Supreme Power of many names as Gagadamba, Mother of the World, which is the Play of Her who is named Lalita," (Sir John Woodroffe). In India, the Great Mother has been worshipped from the Himalayan mountains in the north to Cape Comorin in the extreme south; the word Cape Comorin is a corrupted form of Kanya Kumari or Kumari Devi, the Virgin Daughter, as the goddess is often called. The Vedas speak much of the goddesses. Their images are radiant with beauty, power and intelligence. From the Vedas themselves the Shakta Tantras, cult-books of the Goddess, derive their inspiration. In the Rig-Veda the goddess Sarasvati receives much homage: "Pure, Sarasvati, with all her bounties, rich in thoughts, inspires us towards truth, causes in us the required virtues, Sarasvati by her divinity awakens in us consciousness, illumines us in our thoughts." She is intelligence, science, arts, and all knowledge. The word shakti comes from the root "shak," "to be able, to have power". Any thing, any activity, has power; if the power be not visible, it is latent. -

Lakshmi Against Untouchability: Puranic Texts and Caste in Odisha

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Lakshmi against Untouchability: Puranic Texts and Caste in Odisha RAJ KUMAR Raj Kumar ([email protected]) teaches at the Department of English, University of Delhi. Vol. 54, Issue No. 48, 07 Dec, 2019 The Lakshmi Purana as a literary text primarily raises issues relating to the religious rights of Dalit women in Odisha. Lakshmibrata kathas are stories that are recited while worshipping Lakshmi, the Goddess. Lakshmi, the Goddess of wealth, is now being worshipped all over India. But, the literary sources coming out in various Indian languages prove that the Lakshmibrata kathas originated mostly in the rice-producing states such as, West Bengal (WB), Bihar, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh (AP), Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh (UP). Bidyut Mohanty took nearly 20 years to prove this research hypothesis. His book, Lakshmi, the Rebel: Culture, Economy and Women’s Agency published by Har-Ananad, Delhi, 2019, is an attempt to study caste, culture, and gender, through myths. Taking the Lakshmibrata kathas as tools to investigate the various locations of gendered culture in India, the book connects between the past and the present and makes a bold statement about the degree of women empowerment in India. Mohanty, after critically analysing the Lakshmibrata kathas of various states Mohanty wrote, ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 “We have seen in many countries that political representation and economic opportunities which are indeed absolutely necessary for women’s empowerment have still proved to be inadequate in accomplishing women’s liberation in modern times. In this work, it has been argued that culture has to be an integral component in the composite perspective along with political and economic measures to bring about women’s liberation. -

Shakti and Shkta

Shakti and Shâkta Essays and Addresses on the Shâkta tantrashâstra by Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe), London: Luzac & Co., [1918] Table of Contents Chapter One Indian Religion As Bharata Dharma ........................................................... 3 Chapter Two Shakti: The World as Power ..................................................................... 18 Chapter Three What Are the Tantras and Their Significance? ...................................... 32 Chapter Four Tantra Shastra and Veda .......................................................................... 40 Chapter Five The Tantras and Religion of the Shaktas................................................... 63 Chapter Six Shakti and Shakta ........................................................................................ 77 Chapter Seven Is Shakti Force? .................................................................................... 104 Chapter Eight Cinacara (Vashishtha and Buddha) ....................................................... 106 Chapter Nine the Tantra Shastras in China................................................................... 113 Chapter Ten A Tibetan Tantra ...................................................................................... 118 Chapter Eleven Shakti in Taoism ................................................................................. 125 Chapter Twelve Alleged Conflict of Shastras............................................................... 130 Chapter Thirteen Sarvanandanatha ............................................................................. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

Monumentalizing Tantra: The Multiple Identities of the Hamses'varl Devi Temple and the Bansberia Zamlndari Mohini Datta-Ray Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University, Montreal February 16, 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in Partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Mohini Datta-Ray 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-51369-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-51369-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

El Benarés Tántrico De Bettina Bäumer: La Estética Del Deseo

EL BENARÉS TÁNTRICO DE BETTINA BÄUMER: LA ESTÉTICA DEL DESEO Por María Rosa Fernández Gómez 1 Universidad de Málaga Esta presentación pretende continuar y profundizar en algunos aspectos de otras comunicaciones relativas a mujeres que en el siglo XX y, en el caso de la que yo he elegido, hasta nuestros días, han contribuido decisivamente a la conformación de lo que hoy entendemos por teoría y la historia del arte indio. Intentaré seguir, pues, la estela dejada por Alice Boner, Stella Kramrisch, Kapila Vatsyayan, desarrollando mi intervención acerca de los trabajos e intereses de Bettina Bäumer, gran especialista en la estética india y el pensamiento tántrico del shivaísmo de Cachemira. En su dilatada trayectoria académica, Bäumer ha colaborado con Kapila Vatsyayan a través del Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts en publicaciones sobre arte indio, pero especialmente con Alice Boner, de quien fue su más estrecha colaboradora durante los años setenta y ochenta, mientras vivían ambas en la ciudad de Benarés. En mi estancia en Benarés a finales de los años noventa, tuve la suerte de coincidir con ella y asistir a algunas sesiones de trabajo junto al pandit especialista en shivaísmo tántrico de Cachemira, H.N. Chakravarty. En concreto, a través de mi presentación, me gustaría profundizar en algunos aspectos relativos a las temáticas de sus investigaciones y más concretamente tratar de señalar posibles interconexiones entre el tantrismo, la teoría del arte y la estética india. La ciudad de Benarés me servirá en cierto modo como marco simbólico y metafórico de dicha conexión tántrico-estética, por su importancia capital como foco de difusión del shivaísmo tántrico y por ilustrar desde su geografía sagrada los valores espirituales del agua, tema de este encuentro, en el hinduismo.