James Cohan Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Kit Con Link De Descarga Fotos Ron Mueck

PRESS KIT Departamento de Prensa [+54-11] 4104 1044/43/29 [email protected] www.proa.org - Fundación PROA Av. Pedro de Mendoza 1929 [C1169AAD] Buenos Aires Del 16 de noviembre de 2013 al 23 de febrero de 2014 Woman with Sticks (Mujer con ramas), 2009. Procedimientos y materiales varios 170 x 183 x 120 cm. Colección Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, París Concebida por Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, París Con la colaboración de la Embajada de Francia en Argentina Con el auspicio de Tenaris – Organización Techint RON MUECK Créditos de la exhibición Exposición concebida por Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, París — Curadores Con la colaboración de la Hervé Chandès Embajada de Francia en Argentina Grazia Quaroni — Con el auspicio de Tenaris – Organización Techint Colaboración Embajada de Francia en Argentina — Organización y producción Fondation Cartier pour l´art contemporain, París Ron Mueck Studio, Londres ArteMarca, Sao Paulo Inauguración: sábado 16 de noviembre de 2013 Fundación Proa, Buenos Aires Cierre: domingo 23 de febrero de 2014 — Diseño expositivo Ron Mueck Studio, Londres Fundación Proa, Buenos Aires Departamento de Prensa — Lucía Ledesma Montaje, conservación y registro de obras Ignacio Navarro Ron Mueck Studio, Londres Fundación Proa, Buenos Aires Alejandro Grimoldi Juan Pablo Correa — Prestadores Colección Caldic, Holanda Hauser & Wirth, Suiza Anthony d’Offay Ltd., Inglaterra T [+54 11] 4104 1044/43/29 Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Francia E [email protected] Ron Mueck, Inglaterra — Itinerancia Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, París, Francia: del 16 de abril hasta el 27 de octubre de 2013. PROA www.fondation.cartier.com Fundación Proa, Buenos Aires, Argentina: Fundación PROA del 16 de noviembre 2013 hasta el 23 de febrero 2014 Av. -

VISITOR FIGURES 2015 the Grand Totals: Exhibition and Museum Attendance Numbers Worldwide

SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide VISITOR FIGURES 2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide THE DIRECTORS THE ARTISTS They tell us about their unlikely Six artists on the exhibitions blockbusters and surprise flops that made their careers U. ALLEMANDI & CO. PUBLISHING LTD. EVENTS, POLITICS AND ECONOMICS MONTHLY. EST. 1983, VOL. XXV, NO. 278, APRIL 2016 II THE ART NEWSPAPER SPECIAL REPORT Number 278, April 2016 SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES 2015 Exhibition & museum attendance survey JEFF KOONS is the toast of Paris and Bilbao But Taipei tops our annual attendance survey, with a show of works by the 20th-century artist Chen Cheng-po atisse cut-outs in New attracted more than 9,500 visitors a day to Rio de York, Monet land- Janeiro’s Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil. Despite scapes in Tokyo and Brazil’s economic crisis, the deep-pocketed bank’s Picasso paintings in foundation continued to organise high-profile, free Rio de Janeiro were exhibitions. Works by Kandinsky from the State overshadowed in 2015 Russian Museum in St Petersburg also packed the by attendance at nine punters in Brasilia, Rio, São Paulo and Belo Hori- shows organised by the zonte; more than one million people saw the show National Palace Museum in Taipei. The eclectic on its Brazilian tour. Mgroup of exhibitions topped our annual survey Bernard Arnault’s new Fondation Louis Vuitton despite the fact that the Taiwanese national muse- used its ample resources to organise a loan show um’s total attendance fell slightly during its 90th that any public museum would envy. -

Sculpture As Deconstruction: the Aesthetic Practice of Ron Mueck

VCJ12110.1177/1470357212462672Visual CommunicationCranny-Francis 4626722012 visual communication ARTICLE Sculpture as deconstruction: the aesthetic practice of Ron Mueck ANNE CRANNY-FRANCIS University of Technology, Sydney ABSTRACT This article analyses recent (2009) work of Australian-born, British-based hyperrealist sculptor, Ron Mueck, in order to show how it not only engages with a range of specific contemporary concerns and debates, but also operates as a visual deconstruction of Cartesian subjectivity. In order to identify Mueck’s deconstructive practice, the article uses a combination of multimodal, sensory and discourse analyses to situate Mueck’s work discur- sively and institutionally, and to explore the ways in which it provokes reader engagement. As the author identifies, each of the works – Youth, Still life and Drift – addresses specific issues and they all provoke a self-reflexive engagement that brings together all aspects of viewer engagement (sen- sory, emotional, intellectual, spiritual), challenging the mind/body dichotomy that characterizes the Cartesian subject. KEYWORDS being • discursive • intertextuality • meaning • sculpture • sensory • subjectivity • touch • visuality This article begins by locating the discourses within which Mueck’s work is embedded, which influence viewers’ responses to the sculptures and the mean- ings that they generate. It then considers one major characteristic of Mueck’s sculptures – the contradiction between their hyperrealist surface and non-life size – and relates this specifically to the works’ deconstructive practice. This is followed by an analysis of the three new works from 2009 – Youth, Still life and Drift – that were shown in the Mueck exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria (2010). The analysis discusses both specific meanings of each of these works and the way each contributes to Mueck’s deconstructive practice. -

THE ART NEWSPAPER SPECIAL REPORT Number 267, April 2015 SPECIAL REPORT

SPECIAL REPORT TOP TOP ARTISTS CURATORS Male and pale: The things guess who they learned got the organising their most solo first big exhibitions? show The grand totals: VISITOR exhibition and museum attendance FIGURES 2014 numbers worldwide U. ALLEMANDI & CO. PUBLISHING LTD. EVENTS, POLITICS AND ECONOMICS MONTHLY. EST. 1983, VOL. XXIV, NO. 267, APRIL 2015 2 THE ART NEWSPAPER SPECIAL REPORT Number 267, April 2015 SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES 2014 Exhibition & museum attendance survey The world goes dotty over Yayoi Kusama Taiwan’s National Palace Museum clinches top spot, but Japanese artist’s retrospectives are a phenomenon in South America and Asia eff Koons provided the Whitney Museum Taiwan on top—again Sofía.) The Kusama retrospective packed the former Koons retrospective at the Whitney, the exhibition of American Art with a memorable bon The National Palace Museum in Taipei organised bank’s halls in the Brazilian city, as well as the was only the tenth most visited show in the city voyage before the New York museum the top three best-attended exhibitions in 2014. Instituto Tomie Ohtake in São Paulo, but a contem- (3,869 visitors a day)—four visitors a day ahead of left the Breuer building for its shiny new More than 12,000 visitors a day saw paintings and porary Brazilian artist, Milton Machado, attracted “Italian Futurism” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim home downtown. But when it comes to calligraphic works by Tang Yin (1470-1524); the a fraction more people a day in Rio’s CCBB than Museum, but attracting fewer than Lygia Clark global exhibition attendance, last year show was the third in a quartet of collection-based the Japanese artist. -

Encountering Mimetic Realism: Sculptures by Duane Hanson, Robert Gober, and Ron Mueck

Encountering Mimetic Realism: Sculptures by Duane Hanson, Robert Gober, and Ron Mueck by Monica Ines Huerta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History of Art) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Patricia Simons, Co-Chair Associate Professor Rebecca Zurier, Co-Chair Associate Professor David T. Doris Professor Alexander D. Potts © Monica Ines Huerta All rights reserved 2010 To My Dad ii Acknowledgements Although it can at times feel like an isolating journey, a dissertation is never a solo adventure. There have been many people along the way that have contributed to the progress and completion of this project. I am grateful to my academic advisors who gave generously of their time and expertise. Rebecca Zurier, a supportive advisor, whose historical perspective continuously pushed me to creatively and critically think about the many permutations of realism. Patricia Simons, a wonderfully committed mentor, who asked the tough questions that helped me break through binaries in order to embrace more nuanced arguments. Alex Potts, whose early and ongoing support during my graduate career inspired me to delve deeper into the areas of modern and contemporary sculpture. And last be not least, David Doris, a most welcomed addition to my committee in the later stages of writing and whose creativity I will forever attempt to emulate. I would also like to extend a very warm thank you to the faculty and staff of the Department of the History of Art for their scholastic, financial, and logistical support. I am very thankful to the Ford Foundation for providing the necessary financial backing that allowed me to focus on the research and writing of this document during critical stages of its development. -

Hyperrealism and the Ilusion of Living Being in Contemporary Sculpture

University of Arts and Design Cluj-Napoca I.O.S.U.D. DOCTORAL THESIS HYPERREALISM AND THE ILUSION OF LIVING BEING IN CONTEMPORARY SCULPTURE Scientific coordonator: Ph.D. Prof. Radu-Călin Solovăstru Ph.D. candidate: Felix Deac Cluj - Napoca 2014 CONTENT INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.MORPHOGENESIS, HISTORICAL RESEARCH ............................................................... 3 1.1. Clasification and definition.................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Topic of research and it’s origins .......................................................................................... 6 1.3. Assumptions of Hyperrealism ............................................................................................... 9 1.4. The origins of synthetic materials ....................................................................................... 11 1.5. Hyperrealism and connexions ............................................................................................. 12 1.6. Hyperrealism in sculpture, crhonologic references ........................................................... 19 1.6.1. Duane Hanson the begining of figure production ....................................................... 21 1.6.2. John de Andrea .............................................................................................................. 22 1.6.3. Ron Mueck reproduction of reality -

“Exhibition & Museum Attendance Figures 2011,” the Art Newspaper

! “Exhibition & Museum Attendance Figures 2011,” The Art Newspaper, April 2012. ! THE ART NEWSPAPER, No. 234, APRIL 2012 Visitor figures 35 & Exmuseuhm iabttenidtaincoe fnigures 2011 Brazil’s exhibition boom puts Rio on top Escher worked his magic in Rio, McQueen reigned supreme in New York, but Tokyo hit by after-effects of earthquake hen we be gan our annual sur - TOP TEN vey of the best at - ART MUSEUMS tended exhi- Wbitions in 1996, to make the top 1. LOUVRE, PARIS ten a show needed to attract 8,880,000 around 3,000 visitors a day. In our survey of 2011 shows, to make 2. METROPOLITAN MUSEUM the top ten required almost 7,000 OF ART, NEW YORK visitors a day. Among them was 6,004,254 “Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty”, a posthumous tribute by 3. BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON the Costume Institute of the 5,848,534 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. On average, more than 4. NATIONAL GALLERY, 8,000 people a day went (in total LONDON around 660,000). The must-see 5,253,216 show helped the Met to a record year in our survey, taking its 5. TATE MODERN, LONDON annual total figure to more than 4,802,287 six million, up from 5.2 million in 2010. 6. NATIONAL GALLERY The increase in the number of OF ART, WASHINGTON people going to see the exhibi- 4,392,252 tions in our surveys over the years has been remarkable. In 1996, 7. NATIONAL PALACE around four million people went MUSEUM, TAIPEI to the top ten shows. -

Hors-Série Pendant 12 Mois Numéro 2 / Août1 20139 - Spécial Expositions De L’Été 2013 - * P.3 Paris * P.24 Île-De-France * P.26 Régions * P.75 Étranger

Votre abonnement annuel pour €/mois pendant 12 mois hors-série numéro 2 / août1 20139 - spécial expositions de l’été 2013 - * p.3 paris * p.24 île-de-france * p.26 régions * p.75 étranger www.lequotidiendelart.com 2 euros édito le quotidien de l’art / hors-série / numéro 2 / août 2013 PAGE Expositions : 02 Gioni. Nous proposons aussi dans ce numéro un entretien avec l’artiste représentant la France dans les Giardini, Anri l’été de tous les arts ! Sala. Venise est encore marquée cette année par le remake de l’exposition mythique « Quand les attitudes deviennent La période estivale est toujours un moment riche pour les formes » d’Harald Szeemann imaginée par Germano Celant expositions. Beaucoup de musées proposent en effet durant à la Fondation Prada. Il faut encore souligner l’ouverture de cette période leur plus importante manifestation de l’année. la Herbert Foundation à Gand, en Belgique, un nouveau haut 2013 est bien particulière, notamment pour Marseille qui lieu pour l’histoire de l’art contemporain. Aussi, quelque soit dispose du label de capitale européenne de la Culture. Dans ce votre destination de villégiature, l’art et les artistes vont vous deuxième numéro hors-série du Quotidien de l’Art, qui réunit accompagner tout l’été ! les analyses et critiques des expositions estivales signées de philippe régnier nos critiques d’art et journalistes, en France et à l’étranger, le programme proposé par Marseille Provence 2013 est en Le prochain numéro du Quotidien de l’Art paraîtra le 28 août. bonne place. Du « Grand atelier du midi » aux céramiques de Picasso à Aubagne, du Prix de la Fondation d’entreprise Ricard le quotidien de l’art à la Vieille Charité à « Des images comme des oiseaux », un -- Agence de presse et d’édition de l’art 61, rue du Faubourg saint-denis 75010 p aris accrochage photographique original conçu par les artistes * éditeur : agence de presse et d’édition de l’art, sarl au capital social de 10 000 euros. -

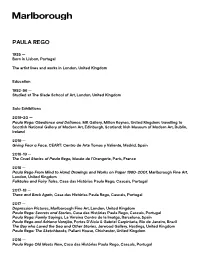

Rego, Paula CV 10 10 19

Marlborough PAULA REGO 1935 — Born in Lisbon, Portugal The artist lives and works in London, United Kingdom Education 1952-56 — Studied at The Slade School of Art, London, United Kingdom Solo Exhibitions 2019-20 — Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance, MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom; travelling to Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland; Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland 2019 — Giving Fear a Face, CEART: Centro de Arte Tomas y Valiente, Madrid, Spain 2018-19 — The Cruel Stories of Paula Rego, Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, France 2018 — Paula Rego From Mind to Hand: Drawings and Works on Paper 1980-2001, Marlborough Fine Art, London, United Kingdom Folktales and Fairy Tales, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal 2017-18 — There and Back Again, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal 2017 — Depression Pictures, Marlborough Fine Art, London, United Kingdom Paula Rego: Secrets and Stories, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal Paula Rego: Family Sayings, La Virreina Centre de la Imatge, Barcelona, Spain Paula Rego and Adriana Varejão, Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel Carpintaria, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil The Boy who Loved the Sea and Other Stories, Jerwood Gallery, Hastings, United Kingdom Paula Rego: The Sketchbooks, Pallant House, Chichester, United Kingdom 2016 — Paula Rego Old Meets New, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal Marlborough Dancing Ostriches, Marlborough Fine Art, London, United Kingdom Paula Rego Paintings and Etchings from the 1980s, Frieze Masters, United -

Contemporary Art in Britain and Its Relationships with Greco-Roman Antiquity

The Classical in the Contemporary: Contemporary Art in Britain and its Relationships with Greco-Roman Antiquity James Matthew Cahill Christ’s College, Cambridge Date of submission: 1 August 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma, or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. Word length: 79,998 words. Summary Title: The Classical in the Contemporary: Contemporary Art in Britain and its Relationships with Greco-Roman Antiquity. James Cahill My thesis is titled ‘The Classical in the Contemporary: Contemporary Art in Britain and its Relationships with Greco-Roman Antiquity.’ From the viewpoint of classical reception studies, I am asking what contemporary British art (by, for example, Sarah Lucas, Damien Hirst, and Mark Wallinger) has to do with the classical tradition – both the art and literature of Greco-Roman antiquity. -

Mark Hughes Financial Revie

Story G JANE O’SULLIVAN Portraits G LOUIE DOUVIS & JOSH ROBENSTONE 54 THE AFR MAGAZINE | MARCH Australian visual artists have traditionally struggled to find traction offshore. But that’s slowly changing – exhibition by exhibition, fair by fair. he second half of 2015 was a pretty crazy She’s not wrong. People from Italy to Argentina would time for Patricia Piccinini. The Melbourne probably recognise Australian actors such as Cate Blanchett, artist opened a large exhibition of work in Nicole Kidman, Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe. Hobart in June. No sooner had she closed Companies such as Circus Oz, the Australian Chamber that exhibition than it was on to solo Orchestra, Sydney Dance Company and the Australian Ballet shows in Galway, Istanbul, Montreal and also have strong reputations offshore, albeit less high profile, São Paulo. The South American exhibition having toured internationally for many decades. Tmoved on to Brasilia at the start of this year and will end up in Australia’s visual artists, by contrast, have not enjoyed Rio de Janeiro in April. Meanwhile, Piccinini’s work featured anything like the same global recognition. There are no in a group show in Seoul, a joint venture between South Australians among the star artists the world’s top dealers Korea’s National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art clamour to represent; no Antony Gormley, Damien Hirst, Ai and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Weiwei, Anselm Kiefer or Anish Kapoor. No Jeff Koons, Piccinini’s weird and wonderful creatures, which explore Richard Serra, Ed Ruscha, William Kentridge or Takashi issues around science and medical developments in a deeply Murakami. -

Media Release 19 October 2017

MEDIA RELEASE 19 OCTOBER 2017 FLESH, BLOOD AND CYBERSPACE: THE FUTURE OF HYPER REAL OPENS AT THE NGA The extraordinary artworks of Hyper Real have been unveiled today at the National Gallery of Australia. Visitors can expect to see a frozen sculpture made entirely of the artist’s blood, a transgenic creature giving birth amidst an infinite meadow and a virtual journey through a human skull floating in space amongst the incredible array of ultra-real sculpture and digital art on display. Hyper Real presents some of the world’s most incredible true-to-life sculpted forms alongside recent kinetic, biological and virtual creations. The exhibition investigates how artists are pushing the boundaries of the genre in their exploration of what constitutes the contemporary hyperreal. ‘Presenting 32 artists and nearly 50 works, Hyper Real focuses on extraordinary talent from around the world,’ said Gerard Vaughan, NGA Director. ‘Most importantly, this exhibition highlights the exceptional contribution of Australian practitioners, including Patricia Piccinini, Sam Jinks, Ron Mueck, Shaun Gladwell, Jan Nelson, Stephen Birch and Ronnie van Hout.’ ‘This exhibition not only celebrates the astonishing material and technical feats that have made hyperrealism such a globally popular genre, but also explores the conceptual framework within which these works operate,’ said Jaklyn Babington, NGA Senior Curator of Contemporary Art. ‘Contemporary hyperrealism has pushed beyond static sculpture and into the digital realm. It is a shape-shifting genre, simultaneously traditional and innovative, familiar and provocative.’ From the Renaissance to the present day, artists have long been fascinated with the human form. Hyperrealism momentarily tricks audiences into believing the artworks to be real and, in doing so, encourages viewers to reconsider what it means to be human.