Lepidodendron and Sigillaria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wec01's SSSS Fossils Test 2019

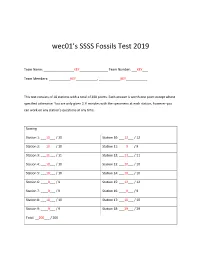

wec01’s SSSS Fossils Test 2019 Team Name: _________________KEY________________ Team Number: ___KEY___ Team Members: ____________KEY____________, ____________KEY____________ This test consists of 18 stations with a total of 200 points. Each answer is worth one point except where specified otherwise. You are only given 2 ½ minutes with the specimens at each station, however you can work on any station’s questions at any time. Scoring Station 1: ___10___ / 10 Station 10: ___12___ / 12 Station 2: ___10___ / 10 Station 11: ____9___ / 9 Station 3: ___11___ / 11 Station 12: ___11___ / 11 Station 4: ___10___ / 10 Station 13: ___10___ / 10 Station 5: ___10___ / 10 Station 14: ___10___ / 10 Station 6: ____9___ / 9 Station 15: ___12___ / 12 Station 7: ____9___ / 9 Station 16: ____9___ / 9 Station 8: ___10___ / 10 Station 17: ___10___ / 10 Station 9: ____9___ / 9 Station 18: ___29___ / 29 Total: __200___ / 200 Team Number: _KEY_ Station 1: Dinosaurs (10 pt) 1. Identify the genus of specimen A Tyrannosaurus (1 pt) 2. Identify the genus of specimen B Stegosaurus (1 pt) 3. Identify the genus of specimen C Allosaurus (1 pt) 4. Which specimen(s) (A, B, or C) are A, C (1 pt) Saurischians? 5. Which two specimens (A, B, or C) lived at B, C (1 pt) the same time? 6. Identify the genus of specimen D Velociraptor (1 pt) 7. Identify the genus of specimen E Coelophysis (1 pt) 8. Which specimen (D or E) is commonly E (1 pt) found in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico? 9. Which specimen (A, B, C, D, or E) would D (1 pt) specimen F have been found on? 10. -

The Largest Tropical Peat Mires in Earth History

Geological Society of America Special Paper 370 2003 Desmoinesian coal beds of the Eastern Interior and surrounding basins: The largest tropical peat mires in Earth history Stephen F. Greb William M. Andrews Cortland F. Eble Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506, USA William DiMichele Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., USA C. Blaine Cecil U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia, USA James C. Hower Center for Applied Energy Research, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA ABSTRACT The Colchester, Springfield, and Herrin Coals of the Eastern Interior Basin are some of the most extensive coal beds in North America, if not the world. The Colchester covers an area of more than 100,000 km^, the Springfield covers 73,500-81,000 km^, and the Herrin spans 73,900 km^. Each has correlatives in the Western Interior Basin, such that their entire regional extent varies from 116,000 km^to 200,000 km^. Correlatives in the Appalachian Basin may indicate an even more widespread area of Desmoinesian peatland development, although possibly sUghtly younger in age. The Colchester Coal is thin, but the Springfield and Herrin Coals reach thicknesses in excess of 3 m. High ash yields, dominance of vitrinite macerals, and abundant lycopsids suggest that these Desmoinesian coals were deposited in topogenous (groundwater fed) to solige- nous (mixed-water source) mires. The only modern mire complexes that are as wide- spread are northern-latitude raised-bog mires, but Desmoinesian -

Retallack 2021 Coal Balls

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 564 (2021) 110185 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Modern analogs reveal the origin of Carboniferous coal balls Gregory Retallack * Department of Earth Science, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1272, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Coal balls are calcareous peats with cellular permineralization invaluable for understanding the anatomy of Coal ball Pennsylvanian and Permian fossil plants. Two distinct kinds of coal balls are here recognized in both Holocene Histosol and Pennsylvanian calcareous Histosols. Respirogenic calcite coal balls have arrays of calcite δ18O and δ13C like Carbon isotopes those of desert soil calcic horizons reflecting isotopic composition of CO2 gas from an aerobic microbiome. Permineralization Methanogenic calcite coal balls in contrast have invariant δ18O for a range of δ13C, and formed with anaerobic microbiomes in soil solutions with bicarbonate formed by methane oxidation and sugar fermentation. Respiro genic coal balls are described from Holocene peats in Eight Mile Creek South Australia, and noted from Carboniferous coals near Penistone, Yorkshire. Methanogenic coal balls are described from Carboniferous coals at Berryville (Illinois) and Steubenville (Ohio), Paleocene lignites of Sutton (Alaska), Eocene lignites of Axel Heiberg Island (Nunavut), Pleistocene peats of Konya (Turkey), and Holocene peats of Gramigne di Bando (Italy). Soils and paleosols with coal balls are neither common nor extinct, but were formed by two distinct soil microbiomes. 1. Introduction and Royer, 2019). Although best known from Euramerican coal mea sures of Pennsylvanian age (Greb et al., 1999; Raymond et al., 2012, Coal balls were best defined by Seward (1895, p. -

The Joggins Fossil Cliffs UNESCO World Heritage Site: a Review of Recent Research

The Joggins Fossil Cliffs UNESCO World Heritage site: a review of recent research Melissa Grey¹,²* and Zoe V. Finkel² 1. Joggins Fossil Institute, 100 Main St. Joggins, Nova Scotia B0L 1A0, Canada 2. Environmental Science Program, Mount Allison University, Sackville, New Brunswick E4L 1G7, Canada *Corresponding author: <[email protected]> Date received: 28 July 2010 ¶ Date accepted 25 May 2011 ABSTRACT The Joggins Fossil Cliffs UNESCO World Heritage Site is a Carboniferous coastal section along the shores of the Cumberland Basin, an extension of Chignecto Bay, itself an arm of the Bay of Fundy, with excellent preservation of biota preserved in their environmental context. The Cliffs provide insight into the Late Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian) world, the most important interval in Earth’s past for the formation of coal. The site has had a long history of scientific research and, while there have been well over 100 publications in over 150 years of research at the Cliffs, discoveries continue and critical questions remain. Recent research (post-1950) falls under one of three categories: general geol- ogy; paleobiology; and paleoenvironmental reconstruction, and provides a context for future work at the site. While recent research has made large strides in our understanding of the Late Carboniferous, many questions remain to be studied and resolved, and interest in addressing these issues is clearly not waning. Within the World Heritage Site, we suggest that the uppermost formations (Springhill Mines and Ragged Reef), paleosols, floral and trace fossil tax- onomy, and microevolutionary patterns are among the most promising areas for future study. RÉSUMÉ Le site du patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO des falaises fossilifères de Joggins est situé sur une partie du littoral qui date du Carbonifère, sur les rives du bassin de Cumberland, qui est une prolongation de la baie de Chignecto, elle-même un bras de la baie de Fundy. -

PRISCUM the Newsletter of the Paleontological Society Volume 13, Number 2, Fall 2004

PRISCUM The Newsletter of the Paleontological Society Volume 13, Number 2, Fall 2004 Paleontological PRESIDENT’S Society Officers COLUMN: Inside... President Treasurer’s Report 2 William I. Ausich WE NEED YOU! GSA Information 2 President-Elect by William I. Ausich Reviews of PS- David Bottjer Sponsored Sessions 3 Past-President Why are you a member of The Paleontology Portal 5 Patricia H. Kelley The Paleontological Society? In PS Lecture Program 6 Secretary the not too distance past, the Books for Review 9 Roger D. K. Thomas only way to receive a copy of the Journal of Book Reviews 9 Treasurer Paleontology and Paleobiology was to pay your dues Conference Announce- and belong to the Society. I suppose one could Mark E. Patzkowsky have borrowed a copy from a friend or wander over ments 14 JP Managing Editors to the library. However, this was probably done Ann (Nancy) F. Budd with a heavy burden of guilt. Now, as we move Christopher A. Brochu into the digital age of scientific journal publishing, Jonathan Adrain one can have copies of the Journal of Paleontology and Paleobiology transmitted right to your Paleobiology Editors computer. It actually may arrive faster than the Tomasz Baumiller U.S. mail, you do not have to pay anything, and Robyn Burnham you do not even have to walk over to the library. Philip Gingerich No need for shelf space, no hassle, no dues, no Program Coordinator guilt – isn’t the Web great? The Web is great, but the Society needs dues-paying members in order Mark A. Wilson to continue to publish in paper, digitally, or both. -

Div B Fossils Answer Key

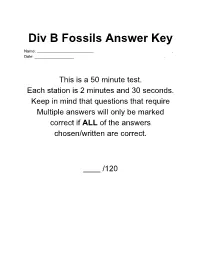

Div B Fossils Answer Key Name: . Date: . This is a 50 minute test. Each station is 2 minutes and 30 seconds. Keep in mind that questions that require Multiple answers will only be marked correct if ALL of the answers chosen/written are correct. /120 Station 1: 1) Brachiosaurus 2) Elmer S. Riggs 3) Diplodocus 4) Cañon City, Colorado 5) Patagotitan 6) Late Cretaceous Station 2: 7) Velociraptor 8) Spinosaurus 9) Plateosaurus 10) Ankylosaurus 11) Parasaurolophus 12) Dracorex Station 3: 13) Platystrophia 14) A, C, D, E 15) Composita 16) Late Devonian-Late Permian 17) Atrypa 18) All around the world Station 4: 19) .Calymene 20) Beautiful crescent, references the glabella 21) Eldredgeops (formerly Phacops) 22) 11 23) Elrathia 24) Four axial rings Station 5: 25) A - Thorax 26) B - Genal Angle 27) C - Cephalon 28) D - Eye 29) E - Pleural furrow 30) F - Librigena 31) G - Fulcrum Station 6: 32) Order Ammonoid 33) Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction even 34) True 35) Planispirals, helically, heteromorphs 36) F Station 7: 37) Class Crinoidea 38) A 39) A characteristic of a species, meaning that it has distinct male and female individual organisms. 40) Yes 41) 600 42) 40 m (130 ft) Station 8: 43) Belemnitella 44) 84.9–66.043 Ma 45) Europe and North America 46) Internal 47) North America 48) True Station 9: 49) Bothriolepis 50) "pitted scale" or "trench scale", either or both accepted 51) Bothriolepis, keyhole, mouth 52) Three 53) a superficial -

Annual Meeting 2002

Newsletter 51 74 Newsletter 51 75 The Palaeontological Association 46th Annual Meeting 15th–18th December 2002 University of Cambridge ABSTRACTS Newsletter 51 76 ANNUAL MEETING ANNUAL MEETING Newsletter 51 77 Holocene reef structure and growth at Mavra Litharia, southern coast of Gulf of Corinth, Oral presentations Greece: a simple reef with a complex message Steve Kershaw and Li Guo Oral presentations will take place in the Physiology Lecture Theatre and, for the parallel sessions at 11:00–1:00, in the Tilley Lecture Theatre. Each presentation will run for a New perspectives in palaeoscolecidans maximum of 15 minutes, including questions. Those presentations marked with an asterisk Oliver Lehnert and Petr Kraft (*) are being considered for the President’s Award (best oral presentation by a member of the MONDAY 11:00—Non-marine Palaeontology A (parallel) Palaeontological Association under the age of thirty). Guts and Gizzard Stones, Unusual Preservation in Scottish Middle Devonian Fishes Timetable for oral presentations R.G. Davidson and N.H. Trewin *The use of ichnofossils as a tool for high-resolution palaeoenvironmental analysis in a MONDAY 9:00 lower Old Red Sandstone sequence (late Silurian Ringerike Group, Oslo Region, Norway) Neil Davies Affinity of the earliest bilaterian embryos The harvestman fossil record Xiping Dong and Philip Donoghue Jason A. Dunlop Calamari catastrophe A New Trigonotarbid Arachnid from the Early Devonian Windyfield Chert, Rhynie, Philip Wilby, John Hudson, Roy Clements and Neville Hollingworth Aberdeenshire, Scotland Tantalizing fragments of the earliest land plants Steve R. Fayers and Nigel H. Trewin Charles H. Wellman *Molecular preservation of upper Miocene fossil leaves from the Ardeche, France: Use of Morphometrics to Identify Character States implications for kerogen formation Norman MacLeod S. -

The Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: B2 the Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: Lyell & Co's "Coal Age Galapagos" J.H

GAC-MAC-CSPG-CSSS Pre-conference Field Trips A1 Contamination in the South Mountain Batholith and Port Mouton Pluton, southern Nova Scotia HALIFAX Building Bridges—across science, through time, around2005 the world D. Barrie Clarke and Saskia Erdmann A2 Salt tectonics and sedimentation in western Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia Ian Davison and Chris Jauer A3 Glaciation and landscapes of the Halifax region, Nova Scotia Ralph Stea and John Gosse A4 Structural geology and vein arrays of lode gold deposits, Meguma terrane, Nova Scotia Rick Horne A5 Facies heterogeneity in lacustrine basins: the transtensional Moncton Basin (Mississippian) and extensional Fundy Basin (Triassic-Jurassic), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia David Keighley and David E. Brown A6 Geological setting of intrusion-related gold mineralization in southwestern New Brunswick Kathleen Thorne, Malcolm McLeod, Les Fyffe, and David Lentz A7 The Triassic-Jurassic faunal and floral transition in the Fundy Basin, Nova Scotia Paul Olsen, Jessica Whiteside, and Tim Fedak Post-conference Field Trips B1 Accretion of peri-Gondwanan terranes, northern mainland Nova Scotia Field Trip B2 and southern New Brunswick Sandra Barr, Susan Johnson, Brendan Murphy, Georgia Pe-Piper, David Piper, and Chris White The Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: B2 The Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: Lyell & Co's "Coal Age Galapagos" J.H. Calder, M.R. Gibling, and M.C. Rygel Lyell & Co's "Coal Age Galapagos” B3 Geology and volcanology of the Jurassic North Mountain Basalt, southern Nova Scotia Dan Kontak, Jarda Dostal, -

Hyperodapedon Gordoni Further Observations Upon

Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University of Virginia on October 5, 2012 Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society Further Observations upon Hyperodapedon Gordoni. T. H. Huxley Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society 1887, v.43; p675-694. doi: 10.1144/GSL.JGS.1887.043.01-04.51 Email alerting click here to receive free service e-mail alerts when new articles cite this article Permission click here to seek permission request to re-use all or part of this article Subscribe click here to subscribe to Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society or the Lyell Collection Notes © The Geological Society of London 2012 Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University of Virginia on October 5, 2012 ON HYPERODAPEDON GORDONL 675 47. FcR~n~l~ O~S~RVAT][O~S upon ~EIYPERODAPEDOI~ GORDON][. By Prof. T. tI. HvxL~, F.R.S., F.G.S. (Read May 11, 1887.) [PLA~ES XXYL & XXVII.] IT is now twenty,nine years since, in describing those remains of Stagonolepis t~obertsoni from the Elgin Sandstones which enabled me to determine the reptilian nature and the crocodilian affinities of that supposed fish, I indicated the occurrence in the same beds of a Laeertilian reptile, to which I gave the name of Hyperodapedon Gordoni. I laid stress upon the " marked affinity with certain Triassic reptiles" (e. g. _Rhynchosaurus)of Hyperodapedon, and I said that these, "when taken together with the resemblance of Stagonolelois to Mesozoic Crocodilia," led me "to require the strongest stratigraphical proof before admitting the Palmozoic age of the beds in which it occurs ,' % Many Fellows of the Society will remember the prolonged dis- cussions which took place, in the course of the ensuing ten or twelve years, before the Mesozoic age of the reptiliferous sandstones of Elgin was universally admitted. -

JOGGINS RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM September 22, 2018

JOGGINS RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM September 22, 2018 2 INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Joggins Fossil Cliffs is celebrating its tenth year as a UNESCO World Heritage Site! To acknowledge this special anniversary, the Joggins Fossil Institute (JFI), and its Science Advisory Committee, organized this symposium to highlight recent and current research conducted at Joggins and work relevant to the site and the Pennsylvanian in general. We organized a day with plenty of opportunity for discussion and discovery so we invite you to share, learn and enjoy your time at the Joggins Fossils Cliffs! The organizing committee appreciates the support of the Atlantic Geoscience Society for this event and in general. Sincerely, JFI Science Advisory Committee, Symposium Subcommittee: Elisabeth Kosters (Chair), Nikole Bingham-Koslowski, Suzie Currie, Lynn Dafoe, Melissa Grey, and Jason Loxton 3 CONTENTS Symposium schedule 4 Technical session schedule 5 Abstracts (arranged alphabetically by first author) 6 Basic Field Guide to the Joggins Formation______________________18 4 SYMPOSIUM SCHEDULE 8:30 – 9:00 am Registration 9:00 – 9:10 am Welcome by Dr. Elisabeth Kosters, JFI Science Advisory Committee Chair 9:10 – 10:30 am Talks 10:25 – 10:40 am Coffee Break and Discussion 10:45 – 12:00 pm Talks and Discussion 12:00 – 1:30 pm Lunch 1:30 – 4:30 pm Joggins Formation Field Trip 4:30 – 6:00 pm Refreshments and Wrap-up 5 TECHNICAL SESSION SCHEDULE Chair: Melissa Grey 9:10 – 9:20 am Peir Pufahl 9:20 – 9:30 am Nikole Bingham-Koslowski 9:30 – 9:40 am Michael Ryan 9:40 – 9:50 am Lynn Dafoe 9:50 – 10:00 am Matt Stimson 10:00 – 10:15 am Olivia King 10:15 – 10:25 am Hillary Maddin COFFEE BREAK Chair: Elisabeth Kosters 10:40 – 10:50 am Martin Gibling 10:50 – 11:00 am Todd Ventura 11:10 – 11:20 am Jason Loxton 11:20 – 11:30 am Nathan Rowbottom 11:30 – 11:40 am John Calder 11:40 – 12:30 Discussion led by Elisabeth Kosters LUNCH 6 ABSTRACTS Breaking down Late Carboniferous fish coprolites from the Joggins Formation NIKOLE BINGHAM-KOSLOWSKI1, MELISSA GREY2, PEIR PUFAHL3, AND JAMES M. -

81 Vascular Plant Diversity

f 80 CHAPTER 4 EVOLUTION AND DIVERSITY OF VASCULAR PLANTS UNIT II EVOLUTION AND DIVERSITY OF PLANTS 81 LYCOPODIOPHYTA Gleicheniales Polypodiales LYCOPODIOPSIDA Dipteridaceae (2/Il) Aspleniaceae (1—10/700+) Lycopodiaceae (5/300) Gleicheniaceae (6/125) Blechnaceae (9/200) ISOETOPSIDA Matoniaceae (2/4) Davalliaceae (4—5/65) Isoetaceae (1/200) Schizaeales Dennstaedtiaceae (11/170) Selaginellaceae (1/700) Anemiaceae (1/100+) Dryopteridaceae (40—45/1700) EUPHYLLOPHYTA Lygodiaceae (1/25) Lindsaeaceae (8/200) MONILOPHYTA Schizaeaceae (2/30) Lomariopsidaceae (4/70) EQifiSETOPSIDA Salviniales Oleandraceae (1/40) Equisetaceae (1/15) Marsileaceae (3/75) Onocleaceae (4/5) PSILOTOPSIDA Salviniaceae (2/16) Polypodiaceae (56/1200) Ophioglossaceae (4/55—80) Cyatheales Pteridaceae (50/950) Psilotaceae (2/17) Cibotiaceae (1/11) Saccolomataceae (1/12) MARATTIOPSIDA Culcitaceae (1/2) Tectariaceae (3—15/230) Marattiaceae (6/80) Cyatheaceae (4/600+) Thelypteridaceae (5—30/950) POLYPODIOPSIDA Dicksoniaceae (3/30) Woodsiaceae (15/700) Osmundales Loxomataceae (2/2) central vascular cylinder Osmundaceae (3/20) Metaxyaceae (1/2) SPERMATOPHYTA (See Chapter 5) Hymenophyllales Plagiogyriaceae (1/15) FIGURE 4.9 Anatomy of the root, an apomorphy of the vascular plants. A. Root whole mount. B. Root longitudinal-section. C. Whole Hymenophyllaceae (9/600) Thyrsopteridaceae (1/1) root cross-section. D. Close-up of central vascular cylinder, showing tissues. TABLE 4.1 Taxonomic groups of Tracheophyta, vascular plants (minus those of Spermatophyta, seed plants). Classes, orders, and family names after Smith et al. (2006). Higher groups (traditionally treated as phyla) after Cantino et al. (2007). Families in bold are described in found today in the Selaginellaceae of the lycophytes and all the pericycle or endodermis. Lateral roots penetrate the tis detail. -

Plant Evolution

Conquering the land The rise of plants Ordovician Spores Algae (algal mats) Green freshwater algae Bacteria Fungae Bryophytes Moses? Liverworts? Little body fossil evidence Silurian Wenlock Stage 423-428mya Psilophytes Rhyniopsidsa important later in early Devonian Cooksonia Rhynia Branching stems, flattened sporangia at tips No leaves, no roots short 30 cms rhizoids Zosterophylls Early stem group of Lycopodiophytes Ancestors of Class Lycopsida (clubmosses) Prevalent in Devonian Spores at tips and on branches Lycopsids (?) Baragwanathia with microphylls in Australia Zosterophylls Silurian Cooksonia Development of Soil Fungae Bacteria Algae Organic matter Arthropods and annelids Change in erosion Change in CO2 Devonian Devonian Early Devonian simple structure Rhynie Chert (Rhyniophytes) Trimerophytes First with main shoot Give rise to Ferns and Progymnosperms Up to 3m tall Animal life (mainly arthropods) Late Devonian Forests First true wood (lignin) Forest structure develops (stories) Sphenopsids (Calamites) Lycopsids (Lepidodendron) Seed Ferns (Pteridosperm) Progymnosperm Archaeopteris Cladoxylopsid First vertebrates present Upper Devonian Lycopsida 374-360 mya Leaves and roots differentiated Most ancient with living relatives Megaphylls branching in on plane Photosynthetic webbing Shrub size vertical growth limited (weak) Lateral (secondary) growth (woody) Development of roots Homosporous Heterosporous Upper Devonian Calamites (Sphenopsid) Horestail Sphenophyta (Calamites-Annularia) Devonian Archaeopteris Ur. Devonian - Lr. Carboniferous