Academy Schools: Case Unproven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of the Ways in Which Faith Is Manifested in Two Primary Schools

An Ethnographic Study of the Ways in Which Faith is Manifested in Two Primary Schools Safia Awad A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Liverpool John Moores University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) January 2015 Contents Page Page Abstract 6 Dedication 8 Abbreviations 9 Chapter 1 – My Background: A Semi-autobiography 10 1.1. Introduction 10 1.2. My Primary Education in Saudi Arabia 12 1.3. My Primary Education in Britain 16 1.4. My Secondary Education 18 1.5. Higher Education 22 1.6. The Context of the Research 25 1.7. Defining the Research Question 29 1.8. Aims of the Research 30 1.9. Definition of Key Terms in this Research 31 1.9.1. School 31 1.9.2. Ethos 31 1.9.3. School Culture 32 1.9.4. Religion 32 1.9.5. Faith 33 1.9.6. Race 34 1.9.7. Racism 35 1.9.8. Ethnicity 35 1.10. Structure of the Thesis 36 1.11. Concluding Remarks 36 Chapter 2 – Historical Perspective of Faith Schools 38 2.1. Introduction 38 2.2. Education in Early nineteenth century 38 2.3. Challenges and Changes of Education 39 2.3.1. Social, political and economic transformation 39 2.3.2. Churches’ Involvement in State Provision 43 2.3.3. Historical Changes: The 1944 Education Act 44 2.3.4. The Education Reform Act 1988 47 2.4. Expansion of Faith School Notion 51 2.4.1. School Choice for Parents 57 2.4.2. Diversity and the Expansion of Faith Schools 59 2.4.3. -

9781529331820 Living Better (495J) - 9Th Pass.Indd 3 26/06/2020 19:59:02 ME, MY LIFE, MY DEPRESSION

1 MY CHILDHOOD, MY FAMILY PRESS On the face of it, I have it all. A wonderful partnerONLY with whom I have shared forty years of my life. Three amaz- ing children who make me incredibly proud to be their dad. I have great friends. A nice home. A dog I love and who loves me even more. MoneyMURRAY is not a problem. I have had several satisfying careers, fi rst as a journalist, then in politics and government. Now I get paid to tour the world and tellJOHN audiencesPURPOSES what I think. I have the freedom to campaign for the causes I believe in, some- thing not always present in my previous two careers: as a journalist I was dependent on events; in politics, I had to subsume REVIEWmy life into the needs and demands of others. With today’s freedom, I can pick and choose, and I do. So when I decided to write this book, for COPYRIGHTexample,FOR I did just that, and pushed other things into the background. Because I can. But there is one major part of my life that I cannot control. Depression. It is a bastard; despite all my good luck and opportunities, all the things that should ensure I am happy and fulfi lled, it keeps coming. This book is 3 9781529331820 Living Better (495j) - 9th pass.indd 3 26/06/2020 19:59:02 ME, MY LIFE, MY DEPRESSION an attempt to explain my depression, to explore it, to make sense of it, properly to understand it – where it may have come from, why it keeps coming and what, if anything, I can do to live a better life despite it. -

Essential Questions for the Future School Addressing the Need for Transformational, Systemic Change to Meet the Needs of Current and Future Learners

Essential questions for the future school Addressing the need for transformational, systemic change to meet the needs of current and future learners September 2006 Future schools Essential questions for the future school Future schools Members of the Futures Vision group of headteachers who have contributed to this publication are: Alison Banks (Principal, Westminster Academy), Jackie Beere Executive summary (Headteacher, Campion School), Simon Brennand (Assistant Head, Philip Morant School), David Broadfield (Headteacher, Robin Hood Primary School), Mike Butler (Principal, The iNet Futures Vision group within the Specialist Schools and Academies Trust (SSAT), Djanogly City Academy), Tom Clark, (Associate Director, SSAT), Steve Gater (Heateacher, exists to stimulate thinking among educators and policymakers through questioning current Walker Technology College), David Harris (Principal, Serlby Park, Business and Enterprise practice and by presenting thought-provoking calls for innovation from practitioners. College), Chris Hummerstone (Headteacher, Arnewood School), Declan Jones (Deputy- Principal, Haberdashers’ Aske’s Hatcham College), Craig Morrison (Assistant Principal, This publication addresses 18 essential questions that need to be answered by schools, Parkside Community College), Paul Roberts (Headteacher, Eaton Bank School), Andy school systems and education leaders if we are to build world class schools for the 21st Schofield (Principal, Varndean School), Elizabeth Sidwell (Chief Executive, Haberdashers century. Askes Foundation), Jeff Threlfall (Headteacher, Wildern School), Ken Walsh (Futures Vision Co-ordinator and Associate Director SSAT) Recommended principles to underpin learning for the future: • The learner is central to all that happens Thanks also to Professor Brian Caldwell and the Futures Vision Principals in Victoria, • The learning process is adapted to suit learners Australia for their contributions to this publication. -

The Introduction of Academy Schools to England's

The Introduction of Academy Schools to England’s Education Andrew Eyles* and Stephen Machin** May 2016 * Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics ** Department of Economics, University College London and Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics Abstract We study the origins of what has become one of the most radical and encompassing programmes of school reform seen in the recent past amongst advanced countries – the introduction of academy schools to English education. Academies are independent state funded schools that are allowed to run in an autonomous manner outside of local authority control. Almost all academies are conversions from already existent state schools and so are school takeovers that enable more autonomy in operation than in their predecessor state. Our analysis shows that the first round of academy conversions that took place in the 2000s, where poorly performing schools were converted to academies, generated significant improvements in the quality of pupil intake and in pupil performance. JEL Keywords: Academies; Pupil Intake; Pupil Performance. JEL Classifications: I20; I21; I28. Acknowledgements This is a very substantively revised and overhauled version of a paper based only on school- level data previously circulated as “Changing School Autonomy: Academy Schools and Their Introduction to England’s Education” (Machin and Vernoit, 2011). It should be viewed as the current version of that paper. We would like to thank the Department for Education for providing access to the pupil-level data we analyse and participants in a large number of seminars and conferences for helpful comments and suggestions. 0 1. Introduction The introduction of academy schools to English education is turning out to be one of the most radical and encompassing programmes of school reform seen in the recent past amongst advanced countries. -

Caroline Benn Memorial Lecture 2006

Caroline Benn Memorial Lecture 2006 Comprehensive schooling: current trends in England and the Nordic countries Lecturer: Peter Montimore I am very pleased to give this lecture. I was a great admirer of Caroline Benn. I met her on a number of occasions when I was working for ILEA and she was a governor of Holland Park School. I have also studied her two excellent books about the struggle for comprehensive education – ‘Half way there’ and ‘Thirty years on’. I admired her not only as a great a advocate of the comprehensive cause but as someone who, unlike those who provide support in principle but consider the system not quite suitable for their own family, chose to entrust her children to a comprehensive school where - as we know from Melissa Benn’s lecture last year – they flourished. In this lecture I will note some of the risks and the potential benefits of using a comparative approach to examine the role and success of school systems. I will then describe briefly some of the characteristics of four of the Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Analyses of the results of an international test of fifteen year-olds[i] will be used to illustrate the performance of these countries in comparison to that of England. I will end by asking the question as to whether there are any lessons that can be learned about comprehensive education from these Nordic countries. First, though, there are a number of caveats to be made. Since my retirement in 2000 I have spent some time in Denmark and Norway as a consultant for the OECD and have visited many schools and spoken to students and teachers. -

The Introduction of Academy Schools to England's Education

IZA DP No. 9276 The Introduction of Academy Schools to England’s Education Andrew Eyles Stephen Machin August 2015 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor The Introduction of Academy Schools to England’s Education Andrew Eyles CEP, London School of Economics Stephen Machin University College London, CEP (LSE) and IZA Discussion Paper No. 9276 August 2015 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. -

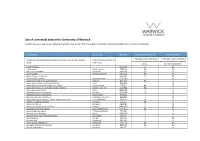

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick The data below will give you an indication of whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for the contextual offer at the University of Warwick. School Name Town / City Postcode School Exam Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school with below 'Y' indcicates a school with above Schools are listed on alphabetical order. Click on the arrow to filter by school Click on the arrow to filter by the national average performance the average entitlement/ eligibility name. Town / City. at KS5. for Free School Meals. 16-19 Abingdon - OX14 1RF N NA 3 Dimensions South Somerset TA20 3AJ NA NA 6th Form at Swakeleys Hillingdon UB10 0EJ N Y AALPS College North Lincolnshire DN15 0BJ NA NA Abbey College, Cambridge - CB1 2JB N NA Abbey College, Ramsey Huntingdonshire PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School Medway ME2 3SP NA Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College Stoke-on-Trent ST2 8LG NA Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton Stockton-on-Tees TS19 8BU NA Y Abbey School, Faversham Swale ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Chippenham Wiltshire SN15 3XB N N Abbeyfield School, Northampton Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School South Gloucestershire BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent East Staffordshire DE15 0JL N Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool Liverpool L25 6EE NA Y Abbotsfield School Hillingdon UB10 0EX Y N Abbs Cross School and Arts College Havering RM12 4YQ N -

Derby City Council Education Commission

APPENDIX 2 DERBY CITY COUNCIL EDUCATION COMMISSION TOPIC REVIEW REPORT SCHOOL PLACE PLANNING IN DERBY SECONDARY SECTOR ISSUES June 2004 CONTENTS Pages Executive Summary Introduction Background to the Topic Review Terms of reference 3 – 12 Topic Review methodology Key Outcomes Collated list of recommendations MAIN REPORT Section 1 Planning the places 13 – 17 Section 2 Secondary School Provision 17 – 20 Section 3 School Planning Pressures 20 – 24 Section 4 Post 16 Issues 24 – 29 Section 5 School Improvement and Standards 29 – 31 Section 6 Special Educational Needs and Disaffection: 31 – 32 Provision and Funding Section 7 National Issues 32 – 34 The evidence from this Topic Review is held by the Overview and Scrutiny Co- ordination Team, Room 137, The Council House, Derby: please telephone the Overview and Scrutiny Team on 01332 255599, or email [email protected] if you require more information. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION This is the unanimous report of the Education Commission following their Topic Review of school place planning relevant to Derby City. The findings from this Topic Review have been presented in two parts. This second part concentrates on issues for Derby City’s secondary schools. The first part, focusing on school place planning in the primary sector, was presented in December 2003. Derby City Education Service includes: • 13 secondary schools, comprising 6 community secondary schools 6 foundation secondary schools 1 Catholic (Aided) secondary school • 80 primary schools made up of: 65 community primary schools 3 foundation primary schools 1 Church of England controlled infant school 6 Church of England aided primary schools 5 Catholic Aided primary schools • 5 special schools • 8 nursery schools • 1 Pupil Referral Unit (PRU) Currently, there are over 35,400 primary and secondary pupils attending schools in the city, not including nursery pupils. -

Creative Writing Phd Thesis by Francis Gilbert...7

Title: Who Do You Love? The Novel of my Life (Creative Writing thesis) and Building Beauty: the Role of Aesthetic Education in my Teaching and Writing Lives (commentary on the Creative Writing thesis) Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Creative Writing By Francis Jonathan Gilbert, Goldsmiths, University of London, August 2015 1 DECLARATION I hereby declare that, except where attribution is made, the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. To the best of my belief this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any degree, except where due acknowledgement has been made. Word count (exclusive of appendix, list of references and bibliography): 115,800 words; the bibliography is 1500 words; and the appendices is 750 words. The main thesis is 80,000 words and the commentary is 35,800 words. Signed: Date: Francis Gilbert 2 Acknowledgments Previous drafts of the Creative Writing thesis Who Do You Love? have appeared in Glits-e in vol. 2, 2011 and Glits-e vol. 4, 2013-2014: Goldsmiths academic online journal. Extracts from my educational commentary, Building Beauty, have appeared in the academic journal English in Education as “But sir, I lied – The value of autobiographical discourse in the classroom”, Vol.46 No.2 2012. I offer sincere thanks to my supervisors for the PhD for all the care and attention they’ve paid to my work: Professor Blake Morrison, Professor Rosalyn George and Chris Kearney. Thanks and gratitude as well to friends and family who have read drafts of the PhD and offered invaluable comments and encouragement: Ella Frears, Jane Harris, Andrea Mason, Toby Mundy, Erica Wagner. -

Academy Schools and Their Introduction to England's Education

Changing School Autonomy: 1 Academy Schools and Their Introduction to England’s Education Stephen Machin *and James Vernoit ** May 2012 * Department of Economics, University College London and Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics ** Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: A small, but growing, literature has begun to explore whether different school types influence pupil achievement. In this paper, we study a high profile example – the introduction of academy schools to the English secondary school sector. Our results indicate that, in some settings, academy conversion generated a significant improvement in the quality of pupil intake and pupil performance. The settings associated with beneficial results arise from heterogeneity in the estimated effects, as improvements only occur for schools that have been established as academies for a sufficiently long period and for those experiencing the largest increase in their school autonomy. JEL Keywords: Academies; Pupil Intake; Pupil Performance. JEL Classifications: I20; I21; I28. 1 Correspondence to be sent to: Stephen Machin. 0 1. Introduction Around the world, it is recognised that a highly educated and skilled workforce is one of the key drivers of a country’s future progress and prosperity. This has led to a keen interest in the types of educational institutions that deliver better outcomes for their students. Unsurprisingly then, the case of schools, and the policies they pursue, has attracted a large amount of attention. Some nations have been innovative in their quest for the optimal school type, while others pursue policies with little deviation from the orthodox model of the traditional local or community school. -

Competition Meets Collaboration

Competition Meets Collaboration Helping school chains address England’s long tail of educational failure James O’Shaughnessy Competition Meets Collaboration Helping school chains address England’s long tail of educational failure James O’Shaughnessy Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Registered charity no: 1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Trustees Daniel Finkelstein (Chairman of the Board), Richard Ehrman (Deputy Chair), Theodore Agnew, Richard Briance, Simon Brocklebank-Fowler, Robin Edwards, Virginia Fraser, Edward Heathcoat Amory, David Meller, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Andrew Sells, Patience Wheatcroft, Rachel Whetstone and Simon Wolfson. About the Author James O’Shaughnessy is Director of Mayforth Consulting, where he leads several projects aimed at reforming publicly-funded schooling in the UK, including working with Wellington College to create an academy chain. He is Chief Policy Adviser to Portland Communications, Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Birmingham’s Jubilee Centre for Character and Values, and a Visiting Fellow at Policy Exchange. James was the Director of Policy to Prime Minister David Cameron between 2010 and 2011, where he was responsible for co-authoring the Coalition’s Programme for Government and overseeing the implementation of the Government’s domestic policy programme. -

PROGRAMME 1968 - the Year of Barricades and Dreams

PROGRAMME 1968 - the year of barricades and dreams. For a moment anything was possible. Twenty years on, the barricades have been dismantled and the dreamsshattered. Marxism Today invites you to revisit that heady fusion of politics and culture Saturday May 7th, 10.00am-6.00pm London School of Economics, Houghton Street, London WC2 Hoi born Tube MORNING 10.30am-12.30pm LATE AFTERNOON 4.30-6.00pm The Experience of '68 (Old Theatre) - DAVID EDGAR and ANNA Significance of '68 (Old Theatre) - STUART HALL reviews the dreams COOTE discuss '68 with ROBIN BLACKBURN and DAVETRIESMAN. that have faded and the hopes that remain for the 1990s. War in Vietnam (Room A86) - Before 1968 the USA boasted that victory Ireland: Banners and Bullets (Room A86) -1968 was the year the in Vietnam was possible. The Tet Offensive shattered the boast. civil rights movement brought Northern Ireland to international attention. Reviewing its impact will be sixties campus activist MICHAEL KLEIN, BERNADETTE McALISKEY, KEN LIVINGSTONE, INEZ McCORMACK JOHN GITTINGS of the Guardian, and the Vietnamese ambassador to and CHRIS MYANTdiscuss the cause of Ireland. Britain. Rebirth of Feminism (Room A85) - The emergence of the Women's Prague Spring (Room A85) - In 1968 Czechoslovakia experienced an Liberation Movement in the late sixties was seen by many as a reaction to exciting, but tragically short, period of socialist democracy. EDUARD the male domination of the events of '68. BEATRIX CAMPBELL, HILARY GOLDSTUCKER, then a member of the Czechoslovakian Communist WAINWRIGHT and MELISSA BENN discuss the significance of the Party's central committee, MARTIN SLING and JON BLOOMFIELD rebirth.