Essential Questions for the Future School Addressing the Need for Transformational, Systemic Change to Meet the Needs of Current and Future Learners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Introduction of Academy Schools to England's

The Introduction of Academy Schools to England’s Education Andrew Eyles* and Stephen Machin** May 2016 * Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics ** Department of Economics, University College London and Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics Abstract We study the origins of what has become one of the most radical and encompassing programmes of school reform seen in the recent past amongst advanced countries – the introduction of academy schools to English education. Academies are independent state funded schools that are allowed to run in an autonomous manner outside of local authority control. Almost all academies are conversions from already existent state schools and so are school takeovers that enable more autonomy in operation than in their predecessor state. Our analysis shows that the first round of academy conversions that took place in the 2000s, where poorly performing schools were converted to academies, generated significant improvements in the quality of pupil intake and in pupil performance. JEL Keywords: Academies; Pupil Intake; Pupil Performance. JEL Classifications: I20; I21; I28. Acknowledgements This is a very substantively revised and overhauled version of a paper based only on school- level data previously circulated as “Changing School Autonomy: Academy Schools and Their Introduction to England’s Education” (Machin and Vernoit, 2011). It should be viewed as the current version of that paper. We would like to thank the Department for Education for providing access to the pupil-level data we analyse and participants in a large number of seminars and conferences for helpful comments and suggestions. 0 1. Introduction The introduction of academy schools to English education is turning out to be one of the most radical and encompassing programmes of school reform seen in the recent past amongst advanced countries. -

The Introduction of Academy Schools to England's Education

IZA DP No. 9276 The Introduction of Academy Schools to England’s Education Andrew Eyles Stephen Machin August 2015 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor The Introduction of Academy Schools to England’s Education Andrew Eyles CEP, London School of Economics Stephen Machin University College London, CEP (LSE) and IZA Discussion Paper No. 9276 August 2015 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. -

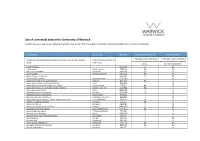

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick The data below will give you an indication of whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for the contextual offer at the University of Warwick. School Name Town / City Postcode School Exam Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school with below 'Y' indcicates a school with above Schools are listed on alphabetical order. Click on the arrow to filter by school Click on the arrow to filter by the national average performance the average entitlement/ eligibility name. Town / City. at KS5. for Free School Meals. 16-19 Abingdon - OX14 1RF N NA 3 Dimensions South Somerset TA20 3AJ NA NA 6th Form at Swakeleys Hillingdon UB10 0EJ N Y AALPS College North Lincolnshire DN15 0BJ NA NA Abbey College, Cambridge - CB1 2JB N NA Abbey College, Ramsey Huntingdonshire PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School Medway ME2 3SP NA Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College Stoke-on-Trent ST2 8LG NA Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton Stockton-on-Tees TS19 8BU NA Y Abbey School, Faversham Swale ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Chippenham Wiltshire SN15 3XB N N Abbeyfield School, Northampton Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School South Gloucestershire BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent East Staffordshire DE15 0JL N Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool Liverpool L25 6EE NA Y Abbotsfield School Hillingdon UB10 0EX Y N Abbs Cross School and Arts College Havering RM12 4YQ N -

Derby City Council Education Commission

APPENDIX 2 DERBY CITY COUNCIL EDUCATION COMMISSION TOPIC REVIEW REPORT SCHOOL PLACE PLANNING IN DERBY SECONDARY SECTOR ISSUES June 2004 CONTENTS Pages Executive Summary Introduction Background to the Topic Review Terms of reference 3 – 12 Topic Review methodology Key Outcomes Collated list of recommendations MAIN REPORT Section 1 Planning the places 13 – 17 Section 2 Secondary School Provision 17 – 20 Section 3 School Planning Pressures 20 – 24 Section 4 Post 16 Issues 24 – 29 Section 5 School Improvement and Standards 29 – 31 Section 6 Special Educational Needs and Disaffection: 31 – 32 Provision and Funding Section 7 National Issues 32 – 34 The evidence from this Topic Review is held by the Overview and Scrutiny Co- ordination Team, Room 137, The Council House, Derby: please telephone the Overview and Scrutiny Team on 01332 255599, or email [email protected] if you require more information. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION This is the unanimous report of the Education Commission following their Topic Review of school place planning relevant to Derby City. The findings from this Topic Review have been presented in two parts. This second part concentrates on issues for Derby City’s secondary schools. The first part, focusing on school place planning in the primary sector, was presented in December 2003. Derby City Education Service includes: • 13 secondary schools, comprising 6 community secondary schools 6 foundation secondary schools 1 Catholic (Aided) secondary school • 80 primary schools made up of: 65 community primary schools 3 foundation primary schools 1 Church of England controlled infant school 6 Church of England aided primary schools 5 Catholic Aided primary schools • 5 special schools • 8 nursery schools • 1 Pupil Referral Unit (PRU) Currently, there are over 35,400 primary and secondary pupils attending schools in the city, not including nursery pupils. -

Academy Schools and Their Introduction to England's Education

Changing School Autonomy: 1 Academy Schools and Their Introduction to England’s Education Stephen Machin *and James Vernoit ** May 2012 * Department of Economics, University College London and Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics ** Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: A small, but growing, literature has begun to explore whether different school types influence pupil achievement. In this paper, we study a high profile example – the introduction of academy schools to the English secondary school sector. Our results indicate that, in some settings, academy conversion generated a significant improvement in the quality of pupil intake and pupil performance. The settings associated with beneficial results arise from heterogeneity in the estimated effects, as improvements only occur for schools that have been established as academies for a sufficiently long period and for those experiencing the largest increase in their school autonomy. JEL Keywords: Academies; Pupil Intake; Pupil Performance. JEL Classifications: I20; I21; I28. 1 Correspondence to be sent to: Stephen Machin. 0 1. Introduction Around the world, it is recognised that a highly educated and skilled workforce is one of the key drivers of a country’s future progress and prosperity. This has led to a keen interest in the types of educational institutions that deliver better outcomes for their students. Unsurprisingly then, the case of schools, and the policies they pursue, has attracted a large amount of attention. Some nations have been innovative in their quest for the optimal school type, while others pursue policies with little deviation from the orthodox model of the traditional local or community school. -

Competition Meets Collaboration

Competition Meets Collaboration Helping school chains address England’s long tail of educational failure James O’Shaughnessy Competition Meets Collaboration Helping school chains address England’s long tail of educational failure James O’Shaughnessy Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Registered charity no: 1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Trustees Daniel Finkelstein (Chairman of the Board), Richard Ehrman (Deputy Chair), Theodore Agnew, Richard Briance, Simon Brocklebank-Fowler, Robin Edwards, Virginia Fraser, Edward Heathcoat Amory, David Meller, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Andrew Sells, Patience Wheatcroft, Rachel Whetstone and Simon Wolfson. About the Author James O’Shaughnessy is Director of Mayforth Consulting, where he leads several projects aimed at reforming publicly-funded schooling in the UK, including working with Wellington College to create an academy chain. He is Chief Policy Adviser to Portland Communications, Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Birmingham’s Jubilee Centre for Character and Values, and a Visiting Fellow at Policy Exchange. James was the Director of Policy to Prime Minister David Cameron between 2010 and 2011, where he was responsible for co-authoring the Coalition’s Programme for Government and overseeing the implementation of the Government’s domestic policy programme. -

Identifying Priority Areas for Raising School Standards

Identifying Priority Areas for Raising School Standards Identifying Local Authority Districts with the lowest proportions of pupils attending OfSTED Good and Outstanding schools June 2021 Contents Introduction 4 Methodology 4 Data Sources 5 Establishment Information 5 OfSTED Inspection Results 5 Pupil Headcount 5 Identifying LADs in Scope 6 Proportion of Pupils attending Good and Outstanding Schools 6 Existing Place-Based Initiatives 6 Opportunity Areas 6 Opportunity North East 6 Annex A: Priority Areas 7 Annex B: School types included in this analysis 9 Introduction This government has focused on raising standards for all pupils over the last decade. We know there are still some parts of the country where standards are too low. DfE is committed to raising school standards in these areas to improve the opportunities available to children and young people across the entire country. Recently the department published a list of areas where standards are weakest as judged by Ofsted, namely the areas in England with the lowest proportion of pupils attending Good and Outstanding schools, as judged by Ofsted as of 31 August 2020. In addition to these areas, the list of priority areas also includes Opportunity Areas (OAs) and Opportunity North East (ONE) given DfE’s existing focus on improving outcomes in these areas. This paper outlines the methodology and data sources used to define the areas. Methodology The analysis focuses simply on the proportion of pupils in each Local Authority District (LAD) attending schools rated Good or Outstanding at their most recent Ofsted inspection. The government’s Opportunity Areas and Opportunity North East areas are also included. -

The Development of the City Technology College Programme: 1980S Conservative Ideas About English Secondary Education

The London School of Economics and Political Science The Development of the City Technology College Programme: 1980s conservative ideas about English secondary education Elizabeth Cookingham Bailey A thesis submitted to the Department of Social Policy of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2016 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 79,742 words. Elizabeth Bailey Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was proofread for conventions of language, spelling, and grammar by Lisa Findley and Chris Grollman. Elizabeth Bailey 2 Abstract This thesis explores the discussion of conservative ideas about secondary education in England between 1979 and 1986. Education policy reforms in the 1980s reflected changing ideologies about the role of the state and about the role of education in society. City Technology Colleges (CTCs), proposed in 1986, embodied many of these changes. -

An Evaluation of the Academies Programme

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Education Resource Archive The Academies programme: Progress, problems and possibilities A report for the Sutton Trust By Andrew Curtis, Sonia Exley, Amanda Sasia, Sarah Tough and Geoff Whitty Institute of Education, University of London December 2008 Contents Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………….. 3 Glossary of terms ……………………………………………………………… 4 Executive Summary …………………………………………………………… 5 The Academies programme: progress, problems and possibilities Introduction ……………………………………………………………. 12 1. Origins of the Academies programme and their performance ……… 14 2. Distinctive aspects of Academies ……………………………………. 22 3. Changes to the Academies Programme ……………………………… 44 4. Emerging Models of Academies ………………………………….… 50 5. Alternatives to Academies ………………………………………..… 68 6. Conclusion …………………………………………………………. 72 7. Policy Implications …………………………………………………. 77 References ……………………………………………………………………. 79 Appendix …………………………………………………………………….. 87 2 Acknowledgements We would like to thank the Sutton Trust for the funds which have made this project possible. We are grateful to the various individuals and organisations who spoke to us about their involvement with the Academies programme. We would also like to thank all the stakeholders who took part in a Roundtable discussion of the issues and for their comments on an early draft of this report. We are particularly grateful to Chris Husbands for his feedback on various drafts and to Nova Matthias for proof -

Dale Bassett Gareth Lyon Will Tanner Bill Watkin March 2012

Plan A+ Unleashing the potential of academies Dale Bassett Gareth Lyon Will Tanner Bill Watkin March 2012 The authors Dale Bassett is Research Director at Reform. Gareth Lyon is Policy and Public Affairs Manager at The Schools Network. Will Tanner is a Researcher at Reform. Bill Watkin is an Operational Director at The Schools Network. The Schools Network The Schools Network is an independent, international, not for profit, membership organisation that works with schools and partners to shape a world class education system. The Schools Network is run by schools, so our programmes and events are designed and delivered by school leaders with inputs from leading academics, thought-leaders and business people. We have a relentless focus on identifying, nurturing, validating and sharing best and next practice in school leadership and teaching and learning globally. We are committed to helping every child to succeed and make a valued contribution to society. Reform Reform is an independent, non-party think tank whose mission is to set out a better way to deliver public services and economic prosperity. Reform is a registered charity, the Reform Research Trust, charity no. 1103739. We believe that by reforming the public sector, increasing investment and extending choice, high quality services can be made available for everyone. Our vision is of a Britain with 21st century healthcare, high standards in schools, a modern and efficient transport system, and a free, dynamic and competitive economy. Plan A+: Unleashing the potential of academies Plan A+ Unleashing the potential of academies Dale Bassett Gareth Lyon Will Tanner Bill Watkin March 2012 1 Plan A+: Unleashing the potential of academies Contents Forewords 3 Executive summary 4 1. -

Opportunities for Schools, Sixth-Form and FE Colleges

PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES Academies and Trusts: Opportunities for schools, PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES sixth-form and FE colleges PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Why should high-performing schools get involved? 4 3. Why should successful colleges get involved? 5 4. What are academies? 6 5. What are trust schools? 7 6. The options 8 a. For maintained schools 8 i) academy sponsorship 8 ii) academy federation 14 b. For FE & sixth-form colleges 18 i) academy sponsorship 18 ii) trust school partnership 18 7. Academies: planning and implementation processes 21 8. Academy governance – the role of sponsors and co-sponsors 22 9. Trust schools: planning and implementation processes 23 10. Trust governance – the role of the trust 24 11. Conclusion – next steps 25 Case studies: G Thomas Telford School 9 G Greensward College, The John Bramston School and The Rickstones School (Essex) 11 G The Priory Federation, Lincolnshire 12 G The Ridings High School and King Edmund Community School (South Gloucestershire) 14 G Haberdasher Academy Federations 16 G Chester-le-Street Learning Community Trust 19 2 Academies and Trusts Opportunities for schools, sixth-form and FE colleges Annexes: G Contacts 26 G Academy and trust school facts and figures 26 G Q&A 28 G Web links to key documents/data 30 G Glossary: types of state school 30 Academies and Trust Opportunities for schools, sixth-form and FE colleges 3 1. -

The Academies Programme: Progress, Problems and Possibilities

The Academies programme: Progress, problems and possibilities A report for the Sutton Trust By Andrew Curtis, Sonia Exley, Amanda Sasia, Sarah Tough and Geoff Whitty Institute of Education, University of London December 2008 Contents Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………….. 3 Glossary of terms ……………………………………………………………… 4 Executive Summary …………………………………………………………… 5 The Academies programme: progress, problems and possibilities Introduction ……………………………………………………………. 12 1. Origins of the Academies programme and their performance ……… 14 2. Distinctive aspects of Academies ……………………………………. 22 3. Changes to the Academies Programme ……………………………… 44 4. Emerging Models of Academies ………………………………….… 50 5. Alternatives to Academies ………………………………………..… 68 6. Conclusion …………………………………………………………. 72 7. Policy Implications …………………………………………………. 77 References ……………………………………………………………………. 79 Appendix …………………………………………………………………….. 87 2 Acknowledgements We would like to thank the Sutton Trust for the funds which have made this project possible. We are grateful to the various individuals and organisations who spoke to us about their involvement with the Academies programme. We would also like to thank all the stakeholders who took part in a Roundtable discussion of the issues and for their comments on an early draft of this report. We are particularly grateful to Chris Husbands for his feedback on various drafts and to Nova Matthias for proof reading the report. 3 Glossary of terms ACE Advisory Centre for Education BSF Building Schools for the Future CTC City Technology