Chess As a Behavioral Model for Cognitive Skill Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1999/6 Layout

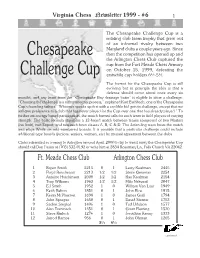

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

Assignment2 Grading Criteria

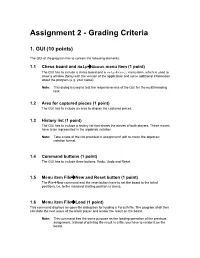

Assignment 2 - Grading Criteria 1. GUI (10 points) The GUI of the program has to contain the following elements: 1.1 Chess board and HelpÆAbout menu item (1 point) The GUI has to include a chess board and a HelpÆAbout menu item, which is used to show a window (form) with the version of the application and some additional information about the program (e.g. your name). Note: This dialog is used to test the responsiveness of the GUI for the multithreading task. 1.2 Area for captured pieces (1 point) The GUI has to include an area to display the captured pieces. 1.3 History list (1 point) The GUI has to include a history list that shows the moves of both players. These moves have to be represented in the algebraic notation. Note: Take a look at the link provided in assignment1.pdf to check the algebraic notation format. 1.4 Command buttons (1 point) The GUI has to include three buttons: Redo, Undo and Reset. 1.5 Menu item FileÆNew and Reset button (1 point) The FileÆNew command and the reset button have to set the board to the initial positions. I.e. to the standard starting position in chess. 1.6 Menu item FileÆLoad (1 point) This command displays an open-file dialog box for loading a Forsyth file. The program shall then calculate the next move of the black player and render the result on the board. Note: This command has the same purpose as the loading operation of the previous assignment. Instead of printing the result in a file, you have to render it on the board. -

Altogether Now in My Decades of Playing Sub-Optimal Chess, I Have

Altogether now In my decades of playing sub-optimal chess, I have been given several pieces of advice about how best to play simultaneous chess. I have faced several grandmasters over the board in simuls and tried to adopt these tips, but with very little success. In fact, no success. One suggestion was to tactically muddy the waters. The theory being if you play a closed positional game the GM (or whoever is giving the simul) will easily overcome you end in the end with their superior technique. On the other hand, although they are, of course, much better than you tactically if they have 20 odd other boards to focus on, effectively playing their moves at a rate akin to blitz, there is a chance they might slip up and give you some winning chances when faced with a messy position. This is fine in theory and may work well for those players stronger then myself who are adept at tactics but my record of my games shows a whopping nil points for me with this approach. In fact, I have found the opposite to be true. I am pleased to report that I have achieved a couple of draws from playing a completely blocked stagnant position. The key here has been to try to make the games last sufficiently long so that in the end then GM kindly offers you a draw in a desperate attempt to get his last bus home. Although loathsome this is when you want as many of those horrible creatures who play on when they are a rook and a bishop down with no compensation (or similar) to keep on playing against the GM. -

PNWCC FIDE Open – Olympiad Gold

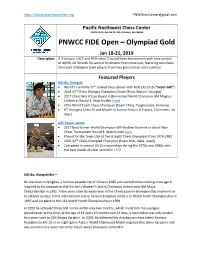

https://www.pnwchesscenter.org [email protected] Pacific Northwest Chess Center 12020 113th Ave NE #C-200, Kirkland, WA 98034 PNWCC FIDE Open – Olympiad Gold Jan 18-21, 2019 Description A 3-section, USCF and FIDE rated 7-round Swiss tournament with time control of 40/90, SD 30 with 30-second increment from move one, featuring two Chess Olympiad Champion team players from two generations and countries. Featured Players GM Bu, Xiangzhi • World’s currently 27th ranked chess player with FIDE Elo 2726 (“Super GM”) • 2018 43rd Chess Olympia Champion (Team China, Batumi, Georgia) • 2017 Chess World Cup Round 4 (Eliminated World Champion GM Magnus Carlsen in Round 3. Watch video here) • 2015 World Team Chess Champion (Team China, Tsaghkadzor, Armenia) • 6th Youngest Chess Grand Master in human history (13 years, 10 months, 13 days) GM Tarjan, James • 2017 Beat former World Champion GM Vladimir Kramnik in Isle of Man Chess Tournament Round 3. Watch video here • Played for the Team USA at five straight Chess Olympiads from 1974-1982 • 1976 22nd Chess Olympiad Champion (Team USA, Haifa, Israel) • Competed in several US Championships during the 1970s and 1980s with the best results of clear second in 1978 GM Bu, Xiangzhi Bio – Bu was born in Qingdao, a famous seaside city of China in 1985 and started chess training since age 6, inspired by his compatriot GM Xie Jun’s Women’s World Champion victory over GM Maya Chiburdanidze in 1991. A few years later Bu easily won in the Chinese junior championship and went on to achieve success in the international arena: he won 3rd place in the U12 World Youth Championship in 1997 and 1st place in the U14 World Youth Championship in 1998. -

1 Forward Search, Pattern Recognition and Visualization in Expert Chess: A

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Brunel University Research Archive 1 Forward search, pattern recognition and visualization in expert chess: A reply to Chabris and Hearst (2003) Fernand Gobet School of Psychology University of Nottingham Address for correspondence: Fernand Gobet School of Psychology University of Nottingham Nottingham NG7 2RD United Kingdom + 44 (115) 951 5402 (phone) + 44 (115) 951 5324 (fax) [email protected] After September 30 th , 2003: Department of Human Sciences Brunel University Uxbridge Middlesex, UB8 3PH United Kingdom [email protected] 2 Abstract Chabris and Hearst (2003) produce new data on the question of the respective role of pattern recognition and forward search in expert behaviour. They argue that their data show that search is more important than claimed by Chase and Simon (1973). They also note that the role of mental imagery has been neglected in expertise research and propose that theories of expertise should integrate pattern recognition, search, and mental imagery. In this commentary, I show that their results are not clear-cut and can also be taken as supporting the predominant role of pattern recognition. Previous theories such as the chunking theory (Chase & Simon, 1973) and the template theory (Gobet & Simon, 1996a), as well as a computer model (SEARCH; Gobet, 1997) have already integrated mechanisms of pattern recognition, forward search and mental imagery. Methods for addressing the respective roles of pattern recognition and search are proposed. Keywords Decision making, expertise, imagery, pattern recognition, problem solving, search 3 Introduction The respective roles of pattern recognition and search in expert problem solving have been an important topic of research in cognitive science. -

Chess Pieces – Left to Right: King, Rook, Queen, Pawn, Knight and Bishop

CCHHEESSSS by Wikibooks contributors From Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". Image licenses are listed in the section entitled "Image Credits." Principal authors: WarrenWilkinson (C) · Dysprosia (C) · Darvian (C) · Tm chk (C) · Bill Alexander (C) Cover: Chess pieces – left to right: king, rook, queen, pawn, knight and bishop. Photo taken by Alan Light. The current version of this Wikibook may be found at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Chess Contents Chapter 01: Playing the Game..............................................................................................................4 Chapter 02: Notating the Game..........................................................................................................14 Chapter 03: Tactics.............................................................................................................................19 Chapter 04: Strategy........................................................................................................................... 26 Chapter 05: Basic Openings............................................................................................................... 36 Chapter 06: -

Colorado Springs Chess Club: Meets Tuesday Evenings, Call (720) 220-5240

Volume 44, Number 2 COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION April 2017 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT Colorado State Scholastic Championship Volume 44, Number 2 Colorado Chess Informant April 2017 From the Editor It would seem to me that the USA is in a bit of a chess expan- sion. With more and more high powered tournaments recently, which included the World Chess Championship last year, Ameri- ca is experiencing some long overdue recognition. And with the introduction of a new chess magazine that focuses The Colorado State Chess Association, Incorporated, is a primarily on the chess scene here in our country, we are slowly Section 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non-profit educational corpora- increasing our chess presence on the world stage. The publishers tion formed to promote chess in Colorado. Contributions are of American Chess Magazine are dedicated to promoting chess tax deductible. in the U.S. with the inaugural issue being released late last year. That issue was jammed-packed with a good representation of Dues are $15 a year or $5 a tournament. Youth (under 20) and various states chess news. I received my copy and enjoyed it so Senior (65 or older) memberships are $10. Family member- much that I subscribed to it right away. If you haven’t had a ships are available to additional family members for $3 off the chance to pick it up, I encourage you to do so - in fact the just regular dues. released second issue has an article about chess in Colorado! ● Send address changes to Dean Clow. All in all some good quality reading. -

The Power of Pawns Chess Structure Fundamentals for Post-Beginners

Jörg Hickl The Power of Pawns Chess Structure Fundamentals for Post-beginners New In Chess 2016 Contents Explanation of Symbols ........................................... 6 Introduction ................................................... 7 Part 1 - Pieces and pawns . 11 Chapter 1 The bishop..........................................12 Chapter 2 The knight ..........................................24 Chapter 3 The rook ...........................................36 Part II - Basic pawn structures . 49 Chapter 4 Hanging pawns ......................................50 Chapter 5 Isolated pawns .......................................62 Chapter 6 Backward pawns......................................86 Chapter 7 Passed pawns .......................................106 Chapter 8 Doubled pawns .....................................123 Chapter 9 Weak squares .......................................141 Chapter 10 Pawn chains ........................................162 Index of Games ............................................... 181 Index of Openings............................................. 183 Bibliography ................................................. 185 5 Introduction What every club player desires is to reach an acceptable playing level with a reasonable expenditure of time and effort. That is the point of the present book ‘The power of the pawns’. An overview of basic pawn structures, together with a lot of practical hints, helps to improve one’s understanding of chess at a deep level. Chess players require a broad spectrum of knowledge. -

Aims: to Enable Participants to Teach Young and Gifted Players In

FIDE Trainers’ Seminar for FIDE Trainer Titles 1. Objective: To educate and certify Trainers and Chess-Teachers on an international basis. This FIDE Trainers’ Seminar for FIDE Trainer Titles Diploma is approved by FIDE and the FIDE Trainers’ Commission (TRG). The seminar is co-organised by the FIDE, the FIDE CACDEC, the FIDE Trainers’ Commission (TRG), the United States Chess Federation (USCF) and the FIDE Academy American Chess University. 2. Dates: August 1st to 2nd, 2013. 3. Location: Madison-Wisconsin, US America (in conjunction with the US Open). 4. Participants - Qualification / Professional Skills Requirements: FIDE/TRG will award the following titles, according to the approved TRG Guide: 1.2. Titles’ Descriptions / Requirements / Awards: 1.2.2. FIDE Trainer (FT) 1.2.2.1. Scope / Mission: a. Boost international level players in achieving playing strengths of up to FIDE ELO rating 2450. b. National examiner. 1.2.2.2. Qualification / Professional Skills Requirements: a. Proof of national trainer education and recommendation for participation by the national federation. b. Proof of at least 5 years activity as a trainer. c. Achieved a career top FIDE ELO rating of 2300 (strength). d. TRG seminar norm. 1.2.2.3. Title Award: a. By successful participation in a TRG Seminar. b. By failing to achieve the FST title (rejected application). 1.2.3. FIDE Instructor (FI) 1.2.3.1. Scope / Mission: a. Raised the competitive standard of national youth players to an international level. b. National examiner. FIDE Trainers’ Seminar - Madison 2013 1 c. Trained players with rating below 2000. 1.2.3.2. -

FIDE Trainers' Commission (TRG) FIDE Trainers' Seminar

FIDE Trainers’ Commission (TRG) FIDE Trainers’ Seminar - Kampala 2015 1. Objective: To educate and certify Chess- 1.2.5.2. Qualification - Professional Skills Teachers on an international basis. This Requirements: FIDE Trainers’ Seminar for FIDE School a. According to the relative evaluation Instructor Diploma is approved by FIDE and tables. the FIDE Trainers’ Commission (TRG). The 1.2.5.3. Title Award: seminar is co-organised by the FIDE, the a. By successful participation in a TRG African Chess Confederation (ACC), the Seminar. FIDE Trainers’ Commission (TRG), the Social Action Commission (SAC) and the 5. Number of Participants: 30 participants Uganda Chess Federation (UCF). maximum will be allowed for the class (first th st come-first served basis). 2. Dates: August 28 to 31 , 2015. 6. Order of Events: 3. Location: Kampala, Uganda. th Friday August 28 17:00-21:00 4. Participants - Qualification / Saturday August 29th 17:00-21:00 Professional Skills Requirements: Sunday August 30th 17:00-21:00 Monday August 31st 11:00-14:00 1.2.4. National Instructor (NI) 7. Lectures / Exercises: The FIDE Trainers 1.2.4.1. Scope - Mission: Seminar will take-up 15 hours. The lectures a. Raising the level of competitive chess will be conducted in the English language players to a national level standard. and a lesson hour equals to 45 minutes. A b. Training trainees with rating up to 1700. projector and a microphone will be in use c. School teacher. during the lectures. 1.2.4.2. Qualification - Professional Skills 8. Trainer Certificate / Diploma: Requirements: a. According to the relative evaluation 1.3. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

Christmas in Pamplona for the Running of the Pawns

‘g’ file exposes the Black king even more. Jakovenko, D- Illescas Cordoba, M January 6th 2007 24.g2xf3 Kg8-h7 Pamplona 2006 25.Rc1–d1 Qd5xa2 The young Russian player Black is forced to win has menacingly massed his another pawn, but the pieces on the kingside so queen is driven offside. Illescas tried to bring his knight over to aid the 26.Ke1–f2 Rf8-f6 defence. 27.Rh1–g1 Ra8-f8 Christmas in 24… Nc7-e8 The hazardous nature of Pamplona Black's position is If 24...Ra8-d8 25.Re3-g3 demonstrated by the fact sets up a decisive sacrifice for the that this natural move loses on g6. by force. Correct was running of 27...Qa2-b3 inching the 25.Ne5xf7 queen back into the game. White has a choice of the pawns 28.Bf4-e5 Nd7xe5 strong moves, 25.Bd3xg6 Chess professionals don’t 29.Qe2xe5 Nb6-d7 f7xg6 26.Re3-g3 was also always get to put their very tempting. feet up over Christmas, as There is no good alternative some tournaments are but this meets with a brutal 25...Rd4xd3 traditionally held during response. this period. This year all XABCDEFGHY Capturing the knight doesn’t eyes were on Pamplona, 8-+-+-tr-+( work: 25...Qg7xf7 where the organisers 7zpp+n+-+k' 26.Re3xe6 Rd4xd3 27.Qh4- assembled an attractive 6-+-sNltr-zp& h8+ Qf7-g8 28.Re6xe8+ field with many strong, 5+Lzp-wQp+-% Ra8xe8 29.Re1xe8+ imaginative, attacking 4-+-+-+-zP$ Kf8xe8 30.Qh8xg8+ leaves players. 3+-+-+P+-# White a queen to the good.