Overview Evolution of the Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Beautiful Family House with Impressive Accommodation

A BEAUTIFUL FAMILY HOUSE WITH IMPRESSIVE ACCOMMODATION AND RURAL OUTLOOKS parsonage farmhouse collingbourne kingston, marlborough, wiltshire A BEAUTIFUL FAMILY HOUSE WITH IMPRESSIVE ACCOMMODATION AND RURAL OUTLOOKS parsonage farmhouse, collingbourne kingston, marlborough, wiltshire Entrance hall w drawing room w dining room w study w kitchen/breakfast room w utility w cloakroom w cellar w master bedroom with en-suite bathroom w 4 further bedrooms w family bathroom w mature garden with swimming pool and pool house w outbuildings w grass tennis court and paddock w in all approximately 1.88 acres Mileage Pewsey 7 miles (London Paddington 70 minutes) w Marlborough 9 miles w Andover 12 miles (London Waterloo 70 minutes) w Hungerford 11 miles w M4 (J14) 14 miles, Salisbury 20 miles (Distances and times approximate) Situation w Parsonage Farmhouse is an attractive former farmhouse situated in Collingbourne Kingston, a popular village to the south of Marlborough. w The village has a public house, church and garage with a shop/post office in nearby Collingbourne Ducis. w The popular market town of Marlborough is about 9 miles to the north with Andover and the A303 being easily accessible to the south. Description w Parsonage Farmhouse is substantial family house with well- proportioned and light accommodation. w Of note is the fantastic kitchen with Aga, stone floor and French windows leading onto a sheltered terrace. w A long hall leads onto an elegant drawing room has high ceilings, an open fire and French windows into the garden. w The beautiful dining room has an open fire and stone mullion windows and overlooks the mature gardens. -

Prayer Cycle March 2021.Pdf

The Lord calls us to do justly, love mercy and walk humbly with God - Micah 6:8 st 1 - St David, Bishop of Menevia, Patron of Wales, c.601 Within our Congregation and Parish: Pam and Sarah Annis, Sue and Terence Tovey, Catherine Woodruff, John Yard All Residents and Visitors of Albert Terrace, Bridewell Street, Hare and Hounds Street, Sutton Place and Tylees Court Those who are frightened in our Parish 2nd – Chad, Bishop of Lichfield, Missionary, 672 Within our Congregation and Parish: Gwendoline Ardley, Richard Barron, Catherine Tarrant, Chris Totney All Residents and Visitors of Broadleas Road, Broadleas Close, Broadleas Crescent, Broadleas Park Within our Parish all Medical and Dental Practices Those who need refuge in our Parish rd 3 Within our Congregation and Parish: Mike and Ros Benson, John and Julia Twentyman, David and Soraya Pegden All Residents and Visitors of Castle Court, Castle Grounds, Castle Lane Within our Parish all Retail Businesses Those who fear in our Parish 4th Within our Congregation and Parish: Stephen and Amanda Bradley, Sarah and Robin Stevens All Residents and Visitors of New Park Street, New Park Road, Chantry Court, Within our Parish all Commercial Businesses and those who are lonely Those who are hungry in our Parish 5th Within our Congregation and Parish: Judy Bridger, Georgina Burge, Charles and Diana Slater. All Residents and Visitors of Hillworth Road, Hillworth Gardens, Charles Morrison Close, John Rennie Close, The Moorlands, Pinetum Close and Westview Crescent Within our Parish all Market Stalls and Stall Holders Those who are in need of a friend in our Parish th 6 Within Churches Together, Devizes: The Church of Our Lady; growing confidence in faith; introductory courses; Alpha, Pilgrim and ongoing study, home groups. -

Local Products Directory Kennet and Avon Canal Mike Robinson

WILTSHIRE OXFORDSHIRE HAMPSHIRE WEST BERKSHIRE UP! ON THE NORTH WESSEX DOWNS Mike Robinson The TV chef on life out of the limelight in Frilsham Ridgeway walks Local Products and rural rambles Directory Step-by-step walks through Find your nearest bakery, picture-postcard scenery brewery or beehive Kennet and Avon Canal Celebrating 200 years A GUIDE TO THE ATTRACTIONS, LEISURE ACTIVITIES, WAYS OF LIFE AND HISTORY OF THE NORTH WESSEX DOWNS – AN AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY 2010 For Wining and Dining, indoors or out The Furze Bush Inn provides TheThe FurzeFurze BushBush formal and informal dining come rain or shine. Ball Hill, Near Newbury Welcome Just 2 miles from Wayfarer’s Walk in the elcome to one of the most beautiful, amazing and varied parts of England. The North Wessex village of Ball Hill, The Furze Bush Inn is one Front cover image: Downs was designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1972, which means of Newbury’s longest established ‘Food Pubs’ White Horse, Cherhill. Wit deserves the same protection by law as National Parks like the Lake District. It’s the job of serving Traditional English Bar Meals and an my team and our partners to work with everyone we can to defend, protect and enrich its natural beauty. excellent ‘A La Carte’ menu every lunchtime Part of the attraction of this place is the sheer variety – chances are that even if you’re local there are from Noon until 2.30pm, from 6pm until still discoveries to be made. Exhilarating chalk downs, rolling expanses of wheat and barley under huge 9.30pm in the evening and all day at skies, sparkling chalk streams, quiet river valleys, heaths, commons, pretty villages and historic market weekends and bank holidays towns, ancient forest and more.. -

WILTSHIRE. F.AR 1111 Sharp Samuel, West End Mill, Donhead Smith Thomas, Everleigh, Marlborough Stride Mrs

TRADES DIRECTORY. J WILTSHIRE. F.AR 1111 Sharp Samuel, West End mill, Donhead Smith Thomas, Everleigh, Marlborough Stride Mrs. Jas. Whiteparish, Salisbury St. Andrew, Salisbury Smith William, Broad Hinton, Swindon Strong George, Rowde, Devizes Sharpe Mrs. Henry, Ludwell, Salisbury Smith William, Winsley, Bradford Strong James, Everleigh, Marlborough Sharpe Hy. Samuel, Ludwell, Salisbury Smith William Hugh, Harpit, Wan- Strong Willialll, Draycot, Marlborough Sharps Frank, South Marston, Swindon borough, ShrivenhamR.S.O. (Berks) Strong William, Pewsey S.O Sharps Robert, South Marston, Swindon Snelgar John, Whiteparish, Salisbury Stubble George, Colerne, Chippenham Sharps W. H. South Marston, Swindon Snelgrove David, Chirton, De,·izes Sumbler John, Seend, Melksham Sheate James, Melksham Snook Brothers, Urchfont, Devizes SummersJ.&J. South Wraxhall,Bradfrd Shefford James, Wilton, Marlborough Snook Albert, South Marston, Swindon Summers Edwd. Wingfield rd. Trowbrdg ShepherdMrs.S.Sth.Burcombe,Salisbury Snook Mrs. Francis, Rowde, Devizes Sutton Edwd. Pry, Purton, Swindon Sheppard E.BarfordSt.Martin,Salisbury Snook George, South Marston, Swindon Sutton Fredk. Brinkworth, Chippenham Shergold John Hy. Chihnark, Salisbury EnookHerbert,Wick,Hannington,Swndn Sutton F. Packhorse, Purton, Swindon ·Sbewring George, Chippenham Snook Joseph, Sedghill, Shaftesbury Sutton Job, West Dean, Salisbury Sidford Frank, Wilsford & Lake farms, Snook Miss Mary, Urchfont, Devizes Sutton·John lllake, Winterbourne Gun- Wilsford, Salisbury Snook Thomas, Urchfont, Devizes ner, Salisbury "Sidford Fdk.Faulston,Bishopstn.Salisbry Snook Worthr, Urchfont, Devizes Sutton Josiah, Haydon, Swindon Sidford James, South Newton, Salisbury Somerset J. Milton Lilborne, Pewsey S.O Sutton Thomas Blake, Hurdcott, Winter Bimkins Job, Bentham, Purton, Swindon Spackman Edward, Axrord, Hungerford bourne Earls, Salisbury Simmons T. GreatSomerford, Chippenhm Spackman Ed. Tytherton, Chippenham Sutton William, West Ha.rnham,Salisbry .Simms Mrs. -

Blewbury Neighbourhood Development Plan Housing Needs Survey: Free-Form Comments This Is a Summary of Open-Ended Comments Made in Response to Questions in the Survey

! !"#$%&'()*#+,-%.&'-../) 0#1#".23#45)6"74) 89:;)<)89=:) "##$%&'($)! %"#$%&'(4#+,-%.&'-../2"74>.',) :;)?2'+")89:;) ! @.45#45A) "##$%&'*!"+!,-.'%./$0!1$2$-!34$-5672)!.%&!8-79%&2.:$-!;677&'%/!'%!<6$2=9->! "##$%&'*!<+!?79)'%/!@$$&)!19-4$>! "##$%&'*!A+!B.%&)(.#$!AC.-.(:$-!"))$))D$%:! "##$%&'*!,+!E'66./$!AC.-.(:$-!"))$))D$%:! ! ! ! ! ! !""#$%&'(!)()!"#$%#&'()*'+'"),-'"./0+1)#%2)3"04%2+#5'"! !"##$%&'(%&()"*+,-./) ! ! ! ! "#$%!&'()!$%!$*+)*+$,*'--.!-)/+!0-'*1! ! !""#$%&'(!!"!!"#$%#&'()*'+'"),-'"./0+1)#%2)3"04%2+#5'"! !"##$%&'(%&()"*+,-./! !"#$%&'($)**+$ !"#$%&%"'#(%)$*+#,)$'*#-.#/0%123$(#4)5%#*3..%$%6#*%1%$#-5%$.0-1*#)"6#7$-3"61)'%$#.0--68"7# 63$8"7# ,%$8-6*# -.# 1%'# 1%)'4%$9# :4%$%# 8*# &-"&%$"# '4)'# .3$'4%$# 4-3*8"7# 6%5%0-,;%"'# 8"# '4%# 5800)7%#&-306#%<)&%$2)'%#'4%#,$-20%;9#!"#'48*#),,%"68<#1%#%<,0-$%#14(#*3&4#,$-20%;*#-&&3$# )"6# &-"*86%$# '4%# ,0)""8"7# ,-08&(# 7386)"&%# '4)'# ;874'# 2%# "%%6%6# 8"# '4%# /0%123$(# =%8742-3$4--6#>%5%0-,;%"'#?0)"#'-#%"*3$%#'4%#*8'3)'8-"#6-%*#"-'#1-$*%"9# @%1%$# -5%$.0-1# -&&3$*# 14%"# $)1+# 3"'$%)'%6# *%1)7%# A1)*'%1)'%$B# 2$8;*# -5%$# .$-;# '4%# ;)"4-0%*#)"6#73008%*#-.#'4%#*%1%$)7%#"%'1-$C#'-#.0--6#0)"6+#7)$6%"*+#$-)6*+#,)'4*#)"6+#8"#'4%# 1-$*'#&)*%*+#,%-,0%D*#4-3*%*9#@3&4#3"'$%)'%6#*%1)7%#8*#"-'#-"0(#3",0%)*)"'#'-#*%%#)"6#*;%00# 23'#8'#)0*-#&)"#,-*%#)#'4$%)'#'-#43;)"#4%)0'4#)"6#'4%#%"58$-";%"'9## E5%$.0-1*# -&&3$# ;-*'# &-;;-"0(# 63$8"7# 4%)5(# $)8".)00# A*'-$;B# %5%"'*# -$# ).'%$# ,%$8-6*# -.# ,$-0-"7%6# $)8".)009# :4%(# )$%# 3*3)00(# &)3*%6# 2(# 0)$7%# 5-03;%*# -.# *3$.)&%# 1)'%$# -$# 7$-3"61)'%$# -

"Riltshire. [ KELLY's

86 DEVJZES. "riLTSHIRE. [ KELLY'S Corpore bion. Cottage Hospital & Provident Dispensary, New Park road,. E. N. Carless M.D. consulting eurgeon; G. S. A. t8g]-8. Waylen, H. J. Mackay M.D. Leonard Raby M.D. &. Mayor-Councillor George Swithin Adee Wazlen. Augustus Vivian Trow l\LB. surgeons; D. Ov.en F.C.A. Ex-Mayor-Alderman George Henry Mead. esq. hon. sec.; 0. Sheppard, assistant sec. ; Miss Mac Beoorder-Francis Reynolds Y. Radcliffe esq. I Mitre donald, matron Court buildings, Temple, London E C. County Court, His Honor William Dundas Gardin~r, judge; Joseph Thornthwaite Jackson B.A. registrar &. .Aldermen. high bailiff; James John Dring, chief clerk. The *Thomas Chandler tGeorge Henry Mead county court is held monthly at the Assize Courts, *Richard Hill tCharles Gillman Northgate street. The following places are included *John Ashley Randell tHerbert B1ggs in the district :-All Oannings, Allington, Alton Barnes, Councillors. Beechingstoke, Bishop's Cannings, Bottlesford, Bourto~ Bromham, Charlton, Chirton, Chittoe, Coat-e, Conock, North Ward. Devizes, Eastoott, Easterton, Enford Combe, Erlestoke,. Presiding Alderman at Ward Elections, Thomas Chandler. Etchilhampton, Fiddington, Fittleton, Great Cheverell,. *William Robbins I §George Catley Haxon-~ etheravon, Hilcot, Horton, Little Cheverell, *William Henry Butcher tHenry Willis Littleton, Lydeway, Marden, Market Lavington, Mars *George T. Smith tJohn Rose ton, North Newnton, Nurstead, Patney, Potterne, §Russell D. Gillman tWilliam Rose Poulshot, Roundway, Rowde, Rushall, Stanton St. §Thomas S. Helms Berna.rd, St. James (Devizes;), Stert, Tilshead, Upavon~ Urchfont, Wedhampton, West Lavington, Wilsford .. South Ward. Woodborough & Worton Presiding Alderman at Ward Elections, Richard Hill. For bankruptcy purpos-es this court is included in tha' *Jonas Strong §Alfred T. -

ALDERBURY Parish: ALL CANNINGS Parish: ALTON Parish

WILTSHIRE COUNCIL WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS APPLICATIONS FOR DEVELOPMENT RECEIVED IN WEEK ENDING 06/11/2020 Parish: ALDERBURY Electoral Division: ALDERBURY AND WHITEPARISH Application Number: 20/06274/FUL Grid Ref: 419778 126178 Applicant: Mr Michael Newbury Applicant Address: Wynn's Paddock Old Southampton Road Whaddon Salisbury SP5 3HD UK Site Location: Wynn's Paddock Old Southampton Road Whaddon Salisbury SP5 3HD Proposal: Change of use of agricultural land for 1 Gypsy/Traveller family pitch with a Static Mobile Home, Dayroom, with parking for a Tourer and 2 vehicle parking spaces together with a treatment plant, the laying of hardstanding and associated ancillary works. Case Officer: Christos Chrysanthou Registration Date: 02/11/2020 Direct Line: 01722 434581 Please send your comments by: 30/11/2020 Parish: ALL CANNINGS Electoral Division: URCHFONT AND THE CANNINGS Application Number: 20/09356/FUL Grid Ref: 407419 162074 Applicant: Mrs Deborah Harris Applicant Address: 11, Mathews Close All Cannings SN10 3NU Site Location: 11 Mathews Close All Cannings SN10 3NU Proposal: Front extension & garage conversion. Case Officer: Helena Carney Registration Date: 03/11/2020 Direct Line: 01225 770334 Please send your comments by: 01/12/2020 Parish: ALTON Electoral Division: PEWSEY VALE Application Number: 20/09130/FUL Grid Ref: 411077 162334 Applicant: Andrew Jenkins Applicant Address: 1 The Bank Alton Barnes East C8 To District Boundary Alton Priors Wiltshire SN8 4JX Site Location: 1 The Bank Alton Barnes East C8 To District Boundary -

Compendium of World War Two Memories

World War Two memories Short accounts of the wartime experiences of individual Radley residents and memories of life on the home front in the village Compiled by Christine Wootton Published on the Club website in 2020 to mark the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War Two Party to celebrate VJ Day in August 1946 Victory over Japan Day (VJ Day) was on 8 August 1945. It's likely the party shown in the photograph above was held in Lower Radley in a field next to the railway line opposite the old village hall. Club member Rita Ford remembers a party held there with the little ones in fancy dress, including Winston Churchill and wife, a soldier and a Spitfire. The photograph fits this description. It's possible the party was one of a series held after 1945 until well into the 1950s to celebrate VE Day and similar events, and so the date of 1946 handwritten on the photograph may indeed be correct. www.radleyhistoryclub.org.uk ABOUT THE PROJECT These accounts prepared by Club member and past chairman, Christine Wootton, have two main sources: • recordings from Radley History Club’s extensive oral history collection • material acquired by Christine during research on other topics. Below Christine explains how the project came about. Some years ago Radley resident, Bill Small, gave a talk at the Radley Retirement Group about his time as a prisoner of war. He was captured in May 1940 at Dunkirk and the 80th anniversary reminded me that I had a transcript of his talk. I felt that it would be good to share his experiences with the wider community and this set me off thinking that it would be useful to record, in an easily accessible form, the wartime experiences of more Radley people. -

SMA 1991.Pdf

C 614 5. ,(-7-1.4" SOUTH MIDLANDS ARCHAEOLOGY The Newsletter of the Council for British Archaeology, South Midlands Group (Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire) NUMBER 21, 1991 CONTENTS Page Spring Conference 1991 1 Bedfordshire Buckinghamshire 39 Northamptonshire 58 Ox-fordshire 79 Index 124 EDITOR: Andrew Pike CHAIRMAN: Dr Richard Ivens Bucks County Museum Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit Technical Centre, Tring Road, 16 Erica Road Halton, Aylesbury, HP22 5PJ Stacey Bushes Milton Keynes MX12 6PA HON SEC: Stephen Coleman TREASURER: Barry Home County Planning Dept, 'Beaumont', Bedfordshire County Council Church End, County Hall, Edlesborough, Bedford. Dunstable, Beds. MX42 9AP LU6 2EP Typeset by Barry Home Printed by Central Printing Section, Bucks County Council ISSN 0960-7552 CBA South Midlands The two major events of CBA IX's year were the AGM and Spring Conference, both of which were very successful. CHAIRMAN'S LETTER Last year's A.G.M. hosted the Beatrice de Cardi lecture and the speaker, Derek Riley, gave a lucid account of his Turning back through past issues of our journal I find a pioneering work in the field of aerial archaeology. CBA's recurrent editorial theme is the parlous financial state of President, Professor Rosemary Cramp, and Director, Henry CBA IX and the likelihood that SMA would have to cease Cleere also attended. As many of you will know Henry publication. Previous corrunittees battled on and continued Cleere retires this year so I would like to take this to produce this valuable series. It is therefore gratifying to opportunity of wishing him well for the future and to thank note that SMA has been singled out as a model example in him for his many years of service. -

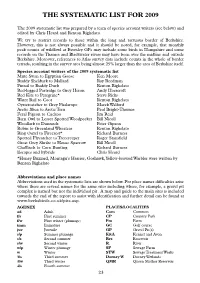

THE Systematic List for 2009

THE SystemaTic List for 2009 The 2009 systematic list was prepared by a team of species account writers (see below) and edited by Chris Heard and Renton Righelato. We try to restrict records to those within the long and tortuous border of Berkshire. However, this is not always possible and it should be noted, for example, that monthly peak counts of wildfowl at Eversley GPs may include some birds in Hampshire and some records on the Thames and Blackwater rivers may have been over the midline and outside Berkshire. Moreover, references to Atlas survey data include counts in the whole of border tetrads, resulting in the survey area being almost 25% larger than the area of Berkshire itself. Species account writers of the 2009 systematic list Mute Swan to Egyptian Goose Ken Moore Ruddy Shelduck to Mallard Ray Reedman Pintail to Ruddy Duck Renton Righelato Red-legged Partridge to Grey Heron Andy Horscroft Red Kite to Peregrine* Steve Ricks Water Rail to Coot Renton Righelato Oystercatcher to Grey Phalarope Marek Walford Arctic Skua to Arctic Tern Paul Bright-Thomas Feral Pigeon to Cuckoo Jim Reid Barn Owl to Lesser Spotted Woodpecker Bill Nicoll Woodlark to Dunnock Peter Gipson Robin to Greenland Wheatear Renton Righelato Ring Ouzel to Firecrest* Richard Burness Spotted Flycatcher to Treecreeper Roger Stansfield Great Grey Shrike to House Sparrow Bill Nicoll Chaffinch to Corn Bunting Richard Burness Escapes and hybrids Chris Heard *Honey Buzzard, Montagu’s Harrier, Goshawk, Yellow-browed Warbler were written by Renton Righelato abbreviations and place names Abbreviations used in the systematic lists are shown below. -

Animal and Human Depictions on Artefacts from Early Anglo-Saxon Graves in the Light of Theories of Material Culture

Animal and human depictions on artefacts from early Anglo-Saxon graves in the light of theories of material culture Submitted by Leah Moradi to the University of Exeter as a dissertation for the degree of Master of Arts by Research in Archaeology in January 2019 This thesis is made available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this dissertation which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: …………………………………………………………. Abstract This dissertation explores the relationship between animal and human motifs on early Anglo-Saxon (AD 450–650) artefacts and the individuals with whom the objects are buried, as well as the wider communities to which they belong. A sample of sites was taken from the two historical regions of East Anglia and Wessex, compiling data such as object type and material, sex and age of individuals, and the human and animal motifs depicted. From a total of 32 sites, 5560 graves were analyzed; of these, 198 graves from 28 sites contained artefacts with anthropomorphic and/or zoomorphic decoration. Anthropological and material culture theories of totemism, shamanism, animism, and object agency were employed in the interpretation of results to consider the symbolic meaning of anthropomorphically- and zoomorphically-decorated objects, and how they may have reflected the social organization and ideologies of communities in early Anglo-Saxon England. -

The Wessex Hillforts Project the Wessex Hillforts Project

The The earthwork forts that crown many hills in Southern England are among the largest and W most dramatic of the prehistoric features that still survive in our modern rural landscape. essex Hillfor The Wessex Hillforts Survey collected wide-ranging data on hillfort interiors in a three-year The Wessex partnership between the former Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage and Oxford University. Hillforts Project These defended enclosures, occupied from the end of the Bronze Age to the last few ts Project Extensive survey of hillfort interiors centuries before the Roman conquest, have long attracted in central southern England archaeological interest and their function remains central Andrew Payne, Mark Corney and Barry Cunliffe to study of the Iron Age. The communal effort and high degree of social organisation indicated by hillforts feeds debate about whether they were strongholds of Celtic chiefs, communal centres of population or temporary gathering places occupied seasonally or in times of unrest. Yet few have been extensively examined archaeologically. Using non-invasive methods, the survey enabled more elaborate distinctions to be made between different classes of hillforts than has hitherto been possible. The new data reveals Andrew P not only the complexity of the archaeological record preserved inside hillforts, but also great variation in complexity among sites. Survey of the surrounding countryside revealed hillforts to be far from isolated features in the later prehistoric landscape. Many have other, a less visible, forms of enclosed settlement in close proximity. Others occupy significant meeting yne, points of earlier linear ditch systems and some appear to overlie, or be located adjacent to, Mark Cor blocks of earlier prehistoric field systems.