Farming Captive Cervids in Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ATLANTA CONSTITUT '' SERVICE Dauy and Sunday, Carrier Delivery, Is Ceata Weekly

ASSOCIATED STANDARD SOUTHERN PRESS NEWSPAPER THE ATLANTA CONSTITUT '' SERVICE DaUy and Sunday, carrier delivery, is ceata weekly. VoL XI/VTL-^No. 229. TLASTTA, GA., , SATUBDAT , JANUARY so, 1915.— FOURTEEN PAGES. Single conic* om toe BtrcetB «md mt aemutaBda. B eeata, Era of Prosperity LOCATION OF GERMAN AlRSHlt* STATIONS FROM WHICH RAIDS CAN BE CONDUCTED Russia Admits Repulse Dawning, Says Wilson; In Carpathian fight; Business Is Now free e On Henceforth Enterprise ^ v Not Be Checkedv , Asserts ROCKEFELLER, )R., Czar's Forces Battling Hard President, and Business in Endeavor to Pierce Not Suspected Simply Be- Through to cause It's Big. " ""' " T^ogress* UNCERTAINTIES REMOVED, LEGISLATION OVER WITH, HAAS IELLS COURT GERMANS DEFEATED > His Philanthropy Never Ex- PROGRESS CAN BE MADE IN ATTEMPT TO CROSS tends to Starving Em- Shows Checks for $500 and AISNE, ASSERTS PARIS ployees in Colorado, De- "Rules of the Game" Are for. $1,000 Givfirt-ftepresen- clares Official of the Mine tativesvfor "V^|||&j>one in Laid Down f of Business in Illaly Preparing for Worst. Workers. 'the Frank>-^^^ Address Before American £Royal Decree Calls VMore "Electric Railway Associa- Soldiers\ to Colors-^TurrvS SAYS THOUSANDS WISH JIM CONLEY ON tion. THEY WERE IN BELGIUM This map' shams in birdseye •d'iew .successfully sent Zeppelins, apparently sen wit/hi aferppla.nes. The1 location of Are Advancing, Cairo Re- iorm the airship situation as far as from Ouamaven or Ayilhelmshaven, to the many 'German airship stations in FQR JUST FIVE MINUTES Yarmouth ; and other toivns within ; a Germany amd Belgium v! from • which v Washington, January 29.--Another the invasion, of England and France hundred miles from Eondon,. -

FRD Northwest 03

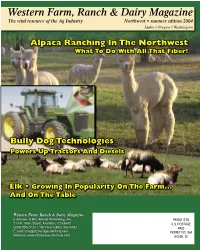

Western Farm, Ranch & Dairy Magazine The vital resource of the Ag Industry Northwest • summer edition 2004 Idaho / Oregon / Washington Alpaca Ranching In The Northwest What To Do With All That Fiber! Bully Dog Technologies Powers Up Tractors And Diesels Elk • Growing In Popularity On The Farm... And On The Table Western Farm, Ranch & Dairy Magazine a division of Ritz Family Publishing, Inc. PRSRT STD 714 N. Main Street, Meridian, ID 83642 U.S. POSTAGE (208) 955-0124 • Toll Free:1(800) 330-3482 PAID E-mail: [email protected] PERMIT NO. 584 Website: www.ritzfamilypublishing.com BOISE, ID 2 • Northwest www.ritzfamilypublishing.com Western Farm, Ranch & Dairy Northwest • 3 4 • Northwest www.ritzfamilypublishing.com contents Western Farm, Ranch & Dairy Magazine Northwest • summer edition 2004 CONTENTS Koehn’s Unique Livestock Handling Products ................................................................. Page 5 Merrick’s Bringing together experience, research, performance and commitment ......... Page 7 PAGE 7 Idaho Firm Recalls Hot Dogs For Undercooking .............................................................. Page 8 Ridley Block Operations ................................................................................................ Page 9 Buffalo Business Moving Toward Greener Economic Pastures ........................................ Page 10 American Angus Association Announces Realignment Of Staff Positions ................... Page 11 Alpaca Produce World-Class, Luxurious Fiber ................................................................ -

An Analysis of the Phylogenetic Relationship of Thai Cervids Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of Protein Kinase C Iota (PRKCI) Intron

Kasetsart J. (Nat. Sci.) 43 : 709 - 719 (2009) An Analysis of the Phylogenetic Relationship of Thai Cervids Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of Protein Kinase C Iota (PRKCI) Intron Kanita Ouithavon1, Naris Bhumpakphan2, Jessada Denduangboripant3, Boripat Siriaroonrat4 and Savitr Trakulnaleamsai5* ABSTRACT The phylogenetic relationship of five Thai cervid species (n=21) and four spotted deer (Axis axis, n=4), was determined based on nucleotide sequences of the intron region of the protein kinase C iota (PRKCI) gene. Blood samples were collected from seven captive breeding centers in Thailand from which whole genomic DNA was extracted. Intron1 sequences of the PRKCI nuclear gene were amplified by a polymerase chain reaction, using L748 and U26 primers. Approximately 552 base pairs of all amplified fragments were analyzed using the neighbor-joining distance matrix method, and 19 parsimony- informative sites were analyzed using the maximum parsimony approach. Phylogenetic analyses using the subfamily Muntiacinae as outgroups for tree rooting indicated similar topologies for both phylogenetic trees, clearly showing a separation of three distinct genera of Thai cervids: Muntiacus, Cervus, and Axis. The study also found that a phylogenetic relationship within the genus Axis would be monophyletic if both spotted deer and hog deer were included. Hog deer have been conventionally classified in the genus Cervus (Cervus porcinus), but this finding supports a recommendation to reclassify hog deer in the genus Axis. Key words: Thailand, the family Cervidae, protein kinase C iota (PRKCI) intron, phylogenetic tree, taxonomy INTRODUCTION 1987; Gentry, 1994). Cervids, or what is commonly called “deer,” are mostly characterized The family Cervidae is one of the most by antlers with a bony inner core and velvet skin specious families of artiodactyls, with an extensive cover. -

RCNA Planchet.Indd

N IO IT ON D 2009PE A SPECIALS RCNARCN CONVENTION EDITION VOL 56. ISSUE 7 August 2009 $4.25 Edmonton RCNA Convention Kicks off As hundreds of convention attendees until the late 1990’s. By 1981 West ood into Edmonton, it is only tting Edmonton Mall the world’s largest that we look back on the history of mall of the time, opened its doors this beautiful city. Anthony Henday, to the public making Edmonton a an explorer hired by the Hudson’s hotspot for tourists from around Bay Company, is thought to be the world. In 1987, an F4 tornado the rst European to set foot in the swept thru Edmonton killing and Edmonton Area in 1754. By 1795 injuring dozens of people. According Fort Edmonton was established to then mayor, Laurence Decore, to facilitate fur trading with the Edmonton’s response showed it to be aboriginal peoples. The name of the a true “City of Champions”. In the This Issue fort was chosen after Edmonton, last decade Edmonton has become England, the home town of the HBC Canada’s economic engine with Anatomy of a Medal governor, Sir James Winter Lake. The many of its residents working in the On L.S.D. rich land and economic prosperity in booming oil sector. Canadian Coin History the region drew many settlers, and in The rst CNA convention to be 1904 Edmonton was incorporated as held in the city took place in 1979, Tax Time a city with a population of 8,350. In then under the Edmonton Coin Club. -

Some Aspects of Moose Domestication (Alces Alces L.) in Russia by T

Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: D Agriculture and Veterinary Volume 19 Issue 5 Version 1.0 Year 2019 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Online ISSN: 2249-4626 & Print ISSN: 0975-5896 Some Aspects of Moose Domestication (Alces Alces L.) in Russia By T. P. Sipko, O. V. Golubev, A. A. Zhiguleva, V. A. Ostapenko, N. S. Marzanov & S. N. Marzanova Summary- Starting with ancient times, some historical stages of moose domestication in Russia are shown. A review of the results of our own research and published data of domestic and foreign authors for the 117-year period (from 1900 to 2018) is presented. Information from regional archival documents and materials of researchers that are not accessible to the general public is presented. It is shown that the moose has a number of positive qualities favoring its introduction to livestock. Due to the domestication of moose, man is given the opportunity to use moose resources more efficiently than by hunting, to obtain additional types of products and to conduct research and educational activities. Keywords: moose, breeding, domestication, history. GJSFR-D Classification: FOR Code: 070799 SomeAspectsofMooseDomesticationAlcesAlcesLinRussia Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2019. T. P. Sipko, O. V. Golubev, A. A. Zhiguleva, V. A. Ostapenko, N. S. Marzanov & S. N. Marzanova. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Exotic Big Game: a Controversial Resource Stephen Demarals, David A

RANGELANDS12(2), April 1990 121 operation was substantially higher because of the addi- allocating15% of the fixed vehiclecosts to the enterprise, tional driving associated with guiding hunters and may the break-even charge is $77.90 per hunter day. In com- also involve picking up hunters in town. Providing guid- paring the break-even chargeswith the estimated fee of ing services requiresadditional labor and includesa cost $111.93, it appears this option is also profitable. for the operator to becomelicensed as an outfitter and Discussion and Conclusions This is a in if the guide. requirement Wyoming hunting Additional income was the reason cited enterpriseused landsnot owned by the operator, includ- primary by lands, or if are hired the operators for beginning a recreation enterprise. While ing public guides by operator. ranch recreationhas the to earna realiz- The budget for Example 2 is shown in Table 2. In this potential profit, the breakeven is hunter ing that potential dependson each operator'ssituation. example charge $24.81 per day. evaluate his the break-even with the estimated fee Eachoperator must particularsituation and Comparing charge consider suchas with the of $36.32 that this of any subjectivefactors, dealing per day (Table 1) suggests type when a ranch recreation is also public, assessing the potential of operation profitable. When landowners and are able to Example 3 describes an agricultural operation that pro- enterprise. recognize realize a situation and other vides 14,400 acres for deer and The profitable through hunting antelope hunting. recreation activitieson their land, wildlife habitat will be hunting enterprise operates for 28 days with thirty-five viewed as an asset and not a customershunting an average of four days per hunteror liability. -

Species Fact Sheet: Sika Deer (Cervus Nippon) [email protected] 023 8023 7874

Species Fact Sheet: Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) [email protected] www.mammal.org.uk 023 8023 7874 Quick Facts Recognition: A medium-sized deer. Has a similar spotted coat to fallow deer in summer, but usually is rougher, thicker, dark grey-brown in winter. Tail is shorter than fallow deer, but with similar white “target” and black margins. Usually has a distinctive “furrowed brow” look, and if seen well, evident white spots on the limbs, marking the site of pedal glands. Males have rounded, not pamate, antlers, looking like a small version of a red deer stag’s antlers. Size: 138-179 cm; Tail length: 14-21cm; Shoulder height 50-120 cm. Weight: Males 40-63kg; females 31-44kg. Life Span: Maximum recorded lifespan in captivity is 26 years; 16 in the wild. Distribution & Habitat Sika are native to SE China, including Taiwan, Korea and Japan. It was introduced to Powerscourt Park, Co Wicklow, Ireland, in 1860, and to London Zoo. Sika then spread to many other parks and escaped or were deliberately released; in some cases they were deliberately released into surrounding woodlands to be hunted on horseback. This resulted in feral populations S England (especially Dorset and the New Forest), in the Forest of Bowland and S Cumbria, and, especially, in Scotland. It is still spreading. Its preference for conifer plantations, especially the thick young stages, has been a big advantage to it. It can reach densities up to 45/km2 in prime habitat. General Ecology Behaviour They typically live in small herds of 6-7 animals, at least in more open habitats, but in dense cover may only live in small groups of 1-3 only. -

Low Sequence Diversity of the Prion Protein Gene (PRNP) in Wild Deer and Goat Species from Spain

Pitarch et al. Vet Res (2018) 49:33 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-018-0528-8 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Low sequence diversity of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in wild deer and goat species from Spain José Luis Pitarch1, Helen Caroline Raksa1, María Cruz Arnal2, Miguel Revilla2, David Martínez2, Daniel Fernández de Luco2, Juan José Badiola1, Wilfred Goldmann3 and Cristina Acín1* Abstract The frst European cases of chronic wasting disease (CWD) in free-ranging reindeer and wild elk were confrmed in Norway in 2016 highlighting the urgent need to understand transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) in the context of European deer species and the many individual populations throughout the European continent. The genetics of the prion protein gene (PRNP) are crucial in determining the relative susceptibility to TSEs. To establish PRNP gene sequence diversity for free-ranging ruminants in the Northeast of Spain, the open reading frame was sequenced in over 350 samples from fve species: Iberian red deer (Cervus elaphus hispanicus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), fallow deer (Dama dama), Iberian wild goat (Capra pyrenaica hispanica) and Pyrenean chamois (Rupicapra p. pyrenaica). Three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were found in red deer: a silent mutation at codon 136, and amino acid changes T98A and Q226E. Pyrenean chamois revealed a silent SNP at codon 38 and an allele with a single octapeptide-repeat deletion. No polymorphisms were found in roe deer, fallow deer and Iberian wild goat. This appar- ently low variability of the PRNP coding region sequences of four major species in Spain resembles previous fndings for wild mammals, but implies that larger surveys will be necessary to fnd novel, low frequency PRNP gene alleles that may be utilized in CWD risk control. -

Estimating Sika Deer Abundance Using Camera Surveys

ESTIMATING SIKA DEER ABUNDANCE USING CAMERA SURVEYS by Sean Q. Dougherty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife Ecology Fall 2010 Copyright 2010 Sean Q. Dougherty All Rights Reserved ESTIMATING SIKA DEER ABUNDANCE USING CAMERA SURVEYS by Sean Q. Dougherty Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Jacob L. Bowman, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Douglas W. Tallamy, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Robin W. Morgan, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture & Natural Resources Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Charles G. Riordan, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the funding sources that made my research possible; the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Research Partnership Grant, the University of Delaware Graduate School, the University of Delaware McNair Scholar’s program, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, University of Delaware Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology, the West Virginia University McNair Scholar’s program, and Tudor Farms LLC. I would also like to thank my committee members Jake Bowman, Greg Shriver, Brian Eyler, and the staff Tudor Farms LLC for all the support and invaluable advice with all aspects of my research and fieldwork. All my friends and family have been especially valuable for their love and support throughout all my endeavors. Finally, I have to acknowledge Traci Hunt for her support, advice and hours of attentiveness throughout the writing portion of my thesis. -

Velvet Antler a Summary of the Literature on Health Benefits

Velvet Antler a summary of the literature on health benefits A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation By Chris Tuckwell November 2003 RIRDC Publication No RIRDC Project No DIP-10A © 2003 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 0642 58651 9 ISSN 1440-6845 Velvet antler – a summary of the literature on health benefits Publication No. 03/084 Project No. DIP-10A The views expressed and the conclusions reached in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of persons consultedP. RIRDC shall not be responsible in any way whatsoever to any person who relies in whole or in part on the contents of this report. This publication is copyright. However, RIRDC encourages wide dissemination of its research, providing the Corporation is clearly acknowledged. For any other enquiries concerning reproduction, contact the Publications Manager on phone 02 6272 3186. Researcher Contact Details Chris Tuckwell Rural Industry Developments PO Box 1105 GAWLER SA 5118 Phone: (08) 8523 3500 Fax: (08) 8523 3301 Email: [email protected] In submitting this report, the researcher has agreed to RIRDC publishing this material in its edited form. RIRDC Contact Details Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Level 1, AMA House 42 Macquarie Street BARTON ACT 2600 PO Box 4776 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Phone: 02 6272 4539 Fax: 02 6272 5877 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.rirdc.gov.au Published in November 2003 Printed on environmentally friendly paper by Canprint ii Foreword RIRDC continues to support research and development projects linked to velvet antler production and marketing as well as many other projects that influence the development of the Australian Deer industry. -

Bioactive Components of Velvet Antlers and Their Pharmacological Properties

Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 87 (2014) 229–240 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jpba Review Bioactive components of velvet antlers and their pharmacological properties Zhigang Sui, Lihua Zhang ∗, Yushu Huo, Yukui Zhang National Chromatographic R. & A. Center, Key Laboratory of Separation Science for Analytical Chemistry, Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Science, Dalian 116023, China a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Velvet antler is one of the most important animal medicines, and has been used with a variety of func- Received 30 April 2013 tions, such as anti-fatigue, tissue repair and health promotion. In the past few years, the investigation on Received in revised form 29 July 2013 chemical compositions, bioactive components, and pharmacological effects has been performed, which Accepted 31 July 2013 demonstrates that velvet antlers could be used as an important health-promoting tonic with great Available online 27 August 2013 nutritional and medicinal values. This review focuses on the recent advance in studying the bioactive components of velvet antlers. Keywords: © 2013 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Velvet antlers Extraction and isolation Analytical techniques Bioactive components Pharmacological effects Contents 1. Introduction . 230 2. Bioactive components. 230 2.1. Amino acids, polypeptides and proteins . 230 2.2. Saccharides . 231 2.3. Lipids and polyamines. 231 3. Preparation of bioactive components. 232 3.1. Extraction and isolation of amino acids, polypeptides and proteins . 232 3.2. -

Evolution of Sambar As Prey of Tiger, Leopard, Wild Dog & Man

Secrets of the Sambar - Vol 3. Evolution of Sambar As Prey of Tiger, Leopard, Wild Dog & Man Sambar have co-evolved as the favourite prey of the tiger for at least twelve thousand years. So it is not surprising that wildlife biologist Dr. A. J. T. Johnsingh tells his students and trainee forest officers that in the hilly areas of India, ‘sambar conservation is tiger conservation’ for sambar are biologically, behaviourally and ecologically adapted to be the best prey of tiger. Dr A. J. T. Johnsingh t is commonly stated by hunters and wildlife Right: The stalk and subsequent pursuit illustrated biologists that sambar are an incredibly elusive on the following pages culminated with the tigress and wary creature whose senses have been delivering one powerful bite, crushing the calves I cervical vertebrae and windpipe. The calf emitted honed to a keen edge as the direct result of having evolved as prey of the tiger. This statement implies a shrieking wail and instantly death was upon it. that sambar evolved through the process of natural As Forest Officer Gobind Sagar Bhardwaj was selection or what is often referred to as ‘survival busy photographing every moment of this once in of the fittest’. That is, those who were best adapted a lifetime wild action, his heart was thumping and to their environment survived to reproduce and he was gushing with adrenalin fueled excitement. pass on their genes to their offspring, and the best adapted offspring survived and passed on their However, tigers do not seem to single out the genes to their offspring and so forth.