View / Open Henderson Oregon 0171N 11882

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2011 Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance Julia A. Fenton University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Motor Control Commons Recommended Citation Fenton, Julia A., "Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance" (2011). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1436 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Principles of Movement Control that Affect Choreographers’ Instruction of Dance Julia Fenton Preface The purpose of this paper is to inform choreographers of different motor control and skill learning principles that affect instruction of dance and choreography as well as provide a resource for choreographers to make rehearsals more productive. In order to accomplish this task, I adapted the information presented in three main texts, written by Schmidt and Wrisberg, Schmidt and Lee, and Fairbrother, in order for it to be useful to choreographers. I have included dance examples rather than sport examples in order for the choreographer to more easily relate to the information. The in-text citations in this paper were kept to a minimum in order for it to be read more easily. -

Is a Genre of Dance Performance That Developed During the Mid-Twentieth

Contemporary Dance Dance 3-4 -Is a genre of dance performance that developed during the mid-twentieth century - Has grown to become one of the dominant genres for formally trained dancers throughout the world, with particularly strong popularity in the U.S. and Europe. -Although originally informed by and borrowing from classical, modern, and jazz styles, it has since come to incorporate elements from many styles of dance. Due to its technical similarities, it is often perceived to be closely related to modern dance, ballet, and other classical concert dance styles. -It also employs contract-release, floor work, fall and recovery, and improvisation characteristics of modern dance. -Involves exploration of unpredictable changes in rhythm, speed, and direction. -Sometimes incorporates elements of non-western dance cultures, such as elements from African dance including bent knees, or movements from the Japanese contemporary dance, Butoh. -Contemporary dance draws on both classical ballet and modern dance -Merce Cunningham is considered to be the first choreographer to "develop an independent attitude towards modern dance" and defy the ideas that were established by it. -Cunningham formed the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 1953 and went on to create more than one hundred and fifty works for the company, many of which have been performed internationally by ballet and modern dance companies. -There is usually a choreographer who makes the creative decisions and decides whether the piece is an abstract or a narrative one. -Choreography is determined based on its relation to the music or sounds that is danced to. . -

Donald Mckayle's Life in Dance

ey rn u In Jo Donald f McKayle’s i nite Life in Dance An exhibit in the Muriel Ansley Reynolds Gallery UC Irvine Main Library May - September 1998 Checklist prepared by Laura Clark Brown The UCI Libraries Irvine, California 1998 ey rn u In Jo Donald f i nite McKayle’s Life in Dance Donald McKayle, performer, teacher and choreographer. His dances em- body the deeply-felt passions of a true master. Rooted in the American experience, he has choreographed a body of work imbued with radiant optimism and poignancy. His appreciation of human wit and heroism in the face of pain and loss, and his faith in redemptive powers of love endow his dances with their originality and dramatic power. Donald McKayle has created a repertory of American dance that instructs the heart. -Inscription on Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival Award orld-renowned choreographer and UCI Professor of Dance Donald McKayle received the prestigious Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival WAward, “established to honor the great choreographers who have dedicated their lives and talent to the creation of our modern dance heritage,” in 1992. The “Sammy” was awarded to McKayle for a lifetime of performing, teaching and creating American modern dance, an “infinite journey” of both creativity and teaching. Infinite Journey is the title of a concert dance piece McKayle created in 1991 to honor the life of a former student; the title also befits McKayle’s own life. McKayle began his career in New York City, initially studying dance with the New Dance Group and later dancing professionally for noted choreographers such as Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, Sophie Maslow, and Anna Sokolow. -

IDO Dance Sports Rules and Regulations 2021

IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations 2021 Officially Declared For further information concerning Rules and Regulations contained in this book, contact the Technical Director listed in the IDO Web site. This book and any material within this book are protected by copyright law. Any unauthorized copying, distribution, modification or other use is prohibited without the express written consent of IDO. All rights reserved. ©2021 by IDO Foreword The IDO Presidium has completely revised the structure of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations. For better understanding, the Rules & Regulations have been subdivided into 6 Books addressing the following issues: Book 1 General Information, Membership Issues Book 2 Organization and Conduction of IDO Events Book 3 Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines Book 4 Code of Ethics / Disciplinary Rules Book 5 Financial Rules and Regulations Separate Book IDO Official´s Book IDO Dancers are advised that all Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines are now contained in Book 3 ("Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines"). IDO Adjudicators are advised that all "General Provisions for Adjudicators and Judging" and all rules for "Protocol and Judging Procedure" (previously: Book 5) are now contained in separate IDO Official´sBook. This is the official version of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations passed by the AGM and ADMs in December 2020. All rule changes after the AGM/ADMs 2020 are marked with the Implementation date in red. All text marked in green are text and content clarifications. All competitors are competing at their own risk! All competitors, team leaders, attendandts, parents, and/or other persons involved in any way with the competition, recognize that IDO will not take any responsibility for any damage, theft, injury or accident of any kind during the competition, in accordance with the IDO Dance Sport Rules. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Second Session Issu July 20, 2016

July 18, 2016 – Second Session Issue July 18, 2016 – Second Session Issu July 20, 2016 – The Dance Night 2k16 Edition Dance Night 2k16 by Robbie Rolfe There could not have been a nicer evening for a very competitive dance night. Special hosts PETE “ME HOW TO DOUGIE” COLE, WILL “MACKERANER” LANE and myself, ROBBIE “ROCK AND ROLFE,” were flown in from all over the world for this spectacular event. Starting the night off were cabin 3. They stepped up on the outside stage, on the top Basketball courts, opposite Wasserman Hall with their song being Flo Rida’s “My House.” It was a brave move for them being the first ones up but they did a really good job with PIERCE MCKENZIE doing a black flip and AARON PELTS doing the worm. They also had some well thought of, homemade props as well to add to their opening routine. Cabin 4 and 5 did “Uptown Funk” by Bruno Mars and the, ever so popular dance move “The Dab” was featured several times during both cabins performances. Cabin 7 did a special performance which was inspired by our very own Woody! Lucky Canteen Number 81. They danced to Michael Jackson’s “Blame it on the Boogie,” and they did the dance routine that Woody teaches everyone during a game of Musical Chairs that he normally hosts during pre-camp or post- camp. Cabin’s 9 and 15 did the “Harlem Shake.” HUNTER ROBERTS was an expert at performing the dance move called “The Wobble,” CALEB SAKS and JACK SACKS picked ROBBIE YASTROW up and did a backwards flip and ZACH MEYERS did the worm very well too. -

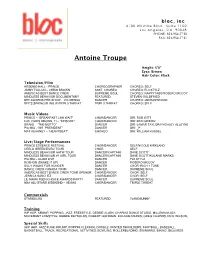

Antoine Troupe

bloc, inc. 6100 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90048 PHONE: 323-954-7730 FAX: 323-954-7731 Antoine Troupe Height: 5’8” Eyes: Brown Hair Color: Black Television/Film ARSENIO HALL - PRINCE CHOREOGRAPHER CHOREO: SELF JIMMY FALLON – CHRIS BROWN ASST. CHOREO CHOREO: FLII STYLZ AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW SUPREME SOUL CHOREO: NAPPYTABS/ROSERO MCCOY MINDLESS BEHAVIOR DOCUMENTARY FEATURED STEVEN GOLDFRIED BET AWARDS PRE-SHOW – VIC MENSA DANCER CHOREO: IAN EASTWOOD BET’S SPRING BLING W/TRIPL3 THREAT TRIPL3 THREAT CHOREO: SELF Music Videos PRINCE – “BREAKFAST CAN WAIT” CHOR/DANCER DIR: ROB WITT E40, CHRIS BROWN, TI – “EPISODE” CHOR/DANCER DIR: BEN GRIFFIN DRAKE – “THE MOTTO” DANCER DIR: LAMAR TAYLOR/HYGHLEY ALLEYNE PIA MIA - “MR. PRESIDENT” DANCER DIR: _P MAT KEARNEY – “HEARTBEAT” CHOREO DIR: WILLIAM RUSSEL Live/Stage Performances PRINCE ESSENCE FESTIVAL CHOR/DANCER SELF/NICOLE KIRKLAND CEELO GREEN EURO TOUR CHOR SELF MINDLESS BEHAVIOR AATW TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT MINDLESS BEHAVIOR #1 GIRL TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT/KOLANIE MARKS PIA MIA – GUAM LIVE DANCER FLII STYLZ ROSHON (SHAKE IT UP) DANCER ROSERO MCCOY SILLY WALKS FOR HUNGER DANCER CHOR: RICH + TONE DANCE CREW CANADA TOUR DANCER SUPREME SOUL AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW TOUR OPENER CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF JESSICA SANCHEZ CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF LIL MAMA TEEN CHOICE AWARDS PARTY DANCER SUPREME SOUL NBA ALL-STARS WEEKEND – VEGAS CHOR/DANCER TRIPLE THREAT Commercials STARBUCKS FEATURED 72ANDSUNNY Training HIP HOP, KRUMP, POPPING, JAZZ, FREESTYLE, DEBBIE ALLEN, CHAPKIS DANCE STUDIO, MILLENIUM, IDA, MOVEMENT LIFESTYLE, DEBBIE REYNOLDS, ROBERT HOFFMAN, KOLANIE MARKS, GREG CHAPKIS, NICK WILSON, Special Skills (HIP HOP, JAZZ FUNK, KRUMP, POPPIN, FLEXING), DOUBLE JOINTED SHOULDERS, FOOTBALL, BASEBALL, BASKETBALL, TRACK, RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES, BOWLING, ROLLERBLADING, SWIMMING, BIKING, BILLIARDS . -

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy And

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tsung-Hsin Lee, M.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Hannah Kosstrin, Advisor Harmony Bench Danielle Fosler-Lussier Morgan Liu Copyrighted by Tsung-Hsin Lee 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation “Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980” examines the transnational history of American modern dance between the United States and Taiwan during the Cold War era. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Carmen De Lavallade-Alvin Ailey, José Limón, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, and Alwin Nikolais dance companies toured to Taiwan under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. At the same time, Chinese American choreographers Al Chungliang Huang and Yen Lu Wong also visited Taiwan, teaching and presenting American modern dance. These visits served as diplomatic gestures between the members of the so-called Free World led by the U.S. Taiwanese audiences perceived American dance modernity through mixed interpretations under the Cold War rhetoric of freedom that the U.S. sold and disseminated through dance diplomacy. I explore the heterogeneous shaping forces from multiple engaging individuals and institutions that assemble this diplomatic history of dance, resulting in outcomes influencing dance histories of the U.S. and Taiwan for different ends. I argue that Taiwanese audiences interpreted American dance modernity as a means of embodiment to advocate for freedom and social change. -

CHOREOGRAPHY BASICS By: Max Perry to Choreograph an Effective Routine, a Dancer Will Use Several Techniques to Create a Dance T

CHOREOGRAPHY BASICS By: Max Perry To choreograph an effective routine, a dancer will use several techniques to create a dance that will not only fit the music, but will feel good when danced. The tools we use as choreographers are knowledge of the dance components, a basic idea of phrasing music, and an idea of how the material is to be used (the dancers or organization or company, etc.). ______________________________________ POINTS TO REMEMBER: 1. “A body in motion tends to stay in motion”. There is an initial force required to put the body in motion. Every time there is a change in the directional movement, there is additional force required to make the change. Too many abrupt changes in direction are not as comfortable as letting the body flow in the direction it wants to go, then gradually slow before changing directions. This does not mean you should slow down before every turn - I am referring to energy output only! 2. Choose music that has a wide audience appeal. You do not want a piece of music that sounds dated. The song should sound good every time it is played. If you want artists to take notice, or a national release, the rule is if you hear the song on the radio, it is too late. These songs were recorded months ago. Major established artists do not need a dance. Never go for the obvious - choose a cut from the album that may be released as a single or use a newer artist - possibly an independent artist. 3. Choose material that has a wide audience appeal. -

Effective Community Engagement Programs in Contemporary Concert Dance Companies

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Mahurin Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects Mahurin Honors College 2021 Effective Community Engagement Programs in Contemporary Concert Dance Companies Emily Caldwell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Education Commons This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mahurin Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFFECTIVE COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROGRAMS IN CONTEMPORARY CONCERT DANCE COMPANIES A Capstone Experience/Thesis Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts with Mahurin Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Emily Caldwell May 2021 ***** CE/T Committee: Prof. Amanda Clark, Chair Prof. Meghen McKinley Dr. Keri Esslinger Copyright by Emily Caldwell 2021 ABSTRACT Arts education is extremely important yet underrated and underfunded in our country today. Some professional dance companies provide educational opportunities in dance and other areas of the arts for youth and others within the community as a means to combat this problem. This project is a compilation and synthesis of my research on how to most effectively create and implement children’s outreach programs in contemporary modern concert dance companies. The purpose of this research is to study how professional dance companies give back to their communities through engagement with children via classes, performances, workshops, etc. and to determine the most effective methods to create, advertise and execute these various programs. -

The THREE's a CROWD

The THREE’S A CROWD exhibition covers areas ranging from Hong Kong to Slavic vixa parties. It looks at modern-day streets and dance floors, examining how – through their physical presence in the public space – bodies create temporary communities, how they transform the old reality and create new conditions. And how many people does it take to make a crowd. The autonomous, affect-driven and confusing social body is a dynamic 19th-century construct that stands in opposition to the concepts of capitalist productivity, rationalism, and social order. It is more of a manifestation of social dis- order: the crowd as a horde, the crowd as a swarm. But it happens that three is already a crowd. The club culture remembers cases of criminalizing the rhythmic movement of at least three people dancing to the music based on repetitive beats. We also remember this pandemic year’s spring and autumn events, when the hearts of the Polish police beat faster at the sight of crowds of three and five people. Bodies always function in relation to other bodies. To have no body is to be nobody. Bodies shape social life in the public space through movement and stillness, gath- ering and distraction. Also by absence. Regardless of whether it is a grassroots form of bodily (dis)organization, self-cho- reographed protests, improvised social dances, artistic, activist or artivist actions, bodies become a field of social and political struggle. Together and apart. ARTISTS: International Festival of Urban ARCHIVES OF PUBLIC Art OUT OF STH VI: SPACE PROTESTS ABSORBENCY -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Artist Title DiscID 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 00321,15543 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10942 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather 05969 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 06024 10cc Donna 03724 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 03126 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 03613 10cc I'm Not In Love 11450,14336 10cc Rubber Bullets 03529 10cc Things We Do For Love, The 14501 112 Dance With Me 09860 112 Peaches & Cream 09796 112 Right Here For You 05387 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 05373 112 & Super Cat Na Na Na 05357 12 Stones Far Away 12529 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 04207 2 Brothers On 4th Come Take My Hand 02283 2 Evisa Oh La La La 03958 2 Pac Dear Mama 11040 2 Pac & Eminem One Day At A Time 05393 2 Pac & Eric Will Do For Love 01942 2 Unlimited No Limits 02287,03057 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 04201 3 Colours Red Beautiful Day 04126 3 Doors Down Be Like That 06336,09674,14734 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 09625 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 02103,07341,08699,14118,17278 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 05609,05779 3 Doors Down Loser 07769,09572 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 10448 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 06477,10130,15151 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain 07992 311 All Mixed Up 14627 311 Amber 05175,09884 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 05267 311 Creatures (For A While) 05243 311 First Straw 05493 311 I'll Be Here A While 09712 311 Love Song 12824 311 You Wouldn't Believe 09684 38 Special If I'd Been The One 01399 38 Special Second Chance 16644 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 05043 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 09798 3LW Playas Gon' Play