Dressing the Dancer: Identity and Belly Dance Students A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IDO Dance Sports Rules and Regulations 2021

IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations 2021 Officially Declared For further information concerning Rules and Regulations contained in this book, contact the Technical Director listed in the IDO Web site. This book and any material within this book are protected by copyright law. Any unauthorized copying, distribution, modification or other use is prohibited without the express written consent of IDO. All rights reserved. ©2021 by IDO Foreword The IDO Presidium has completely revised the structure of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations. For better understanding, the Rules & Regulations have been subdivided into 6 Books addressing the following issues: Book 1 General Information, Membership Issues Book 2 Organization and Conduction of IDO Events Book 3 Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines Book 4 Code of Ethics / Disciplinary Rules Book 5 Financial Rules and Regulations Separate Book IDO Official´s Book IDO Dancers are advised that all Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines are now contained in Book 3 ("Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines"). IDO Adjudicators are advised that all "General Provisions for Adjudicators and Judging" and all rules for "Protocol and Judging Procedure" (previously: Book 5) are now contained in separate IDO Official´sBook. This is the official version of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations passed by the AGM and ADMs in December 2020. All rule changes after the AGM/ADMs 2020 are marked with the Implementation date in red. All text marked in green are text and content clarifications. All competitors are competing at their own risk! All competitors, team leaders, attendandts, parents, and/or other persons involved in any way with the competition, recognize that IDO will not take any responsibility for any damage, theft, injury or accident of any kind during the competition, in accordance with the IDO Dance Sport Rules. -

Belly Dancing in New Zealand

BELLY DANCING IN NEW ZEALAND: IDENTITY, HYBRIDITY, TRANSCULTURE A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Cultural Studies in the University of Canterbury by Brigid Kelly 2008 Abstract This thesis explores ways in which some New Zealanders draw on and negotiate both belly dancing and local cultural norms to construct multiple local and global identities. Drawing upon discourse analysis, post-structuralist and post-colonial theory, it argues that belly dancing outside its cultures of origin has become globalised, with its own synthetic culture arising from complex networks of activities, objects and texts focused around the act of belly dancing. This is demonstrated through analysis of New Zealand newspaper accounts, interviews, focus group discussion, the Oasis Dance Camp belly dance event in Tongariro and the work of fusion belly dance troupe Kiwi Iwi in Christchurch. Bringing New Zealand into the field of belly dance study can offer deeper insights into the processes of globalisation and hybridity, and offers possibilities for examination of the variety of ways in which belly dance is practiced around the world. The thesis fills a gap in the literature about ‘Western’ understandings and uses of the dance, which has thus far heavily emphasised the United States and notions of performing as an ‘exotic Other’. It also shifts away from a sole focus on representation to analyse participants’ experiences of belly dance as dance, rather than only as performative play. The talk of the belly dancers involved in this research demonstrates the complex and contradictory ways in which they articulate ideas about New Zealand identities and cultural conventions. -

Middle Eastern Music and Dance Since the Nightclub Era

W&M ScholarWorks Arts & Sciences Book Chapters Arts and Sciences 10-30-2005 Middle Eastern Music and Dance since the Nightclub Era Anne K. Rasmussen William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons Recommended Citation Rasmussen, A. K. (2005). Middle Eastern Music and Dance since the Nightclub Era. Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young (Ed.), Belly Dance: Orientalism, Transnationalism, And Harem Fantasy (pp. 172-206). Mazda Publishers. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters/102 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. B E L L .v C)ri enta ·l•i S.:I_I_ Transnationalism & Harem Fantasy FFuncling�orthe publication ofthis v\olume w\ as pro\Iv idcd in part by a grant from ✓ Ther Iranic a Institute, Irv\i ine California and b)y TThe C A. K. Jabbari Trust Fund Mazda Publisher• s Academic Publishers P.O. Box 2603 Co st a Mesa, CCa lifornia 92626 Us .S. A . \\ ww.mazdapub.com Copyright © 2005 by Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young All rights resserved. ' No parts of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted by any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and re iews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Belly Dance: Orientalism. -

Competition Rule Book

NCA COLLEGE COMPETITION RULES COMPETITIONNCA & NDA RESERVES THE RIGHT TO BE THE ARBITRATOR RULE AND INTERPRETER OF ALL RULES BOOK COVERED IN THIS DOCUMENT. FOR COLLEGE TEAMS NCA & NDA COLLEGIATE CHEER AND DANCE CHAMPIONSHIP Daytona Beach, Florida April 7-11, 2021 UPDATED AS OF 3/9/21 COLLEGIATE RULE BOOK • 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS NCA & NDA RESERVES THE RIGHT TO BE THE ARBITRATOR AND INTERPRETER OF ALL RULES COVERED IN THIS DOCUMENT. HOW TO QUALIFY 1 DANCE CONT. NCA VIDEO QUALIFICATION AND ENTRY FORMAT 1 NDA LEGALITY AND SAFETY NDA VIDEO QUALIFICATION AND ENTRY FORMAT 2 SAFETY GUIDELINES 27 CODE OF CONDUCT 3 TUMBLING AND AERIAL STREET SKILLS (INDIVIDUALS) 27 EXCLUSIVITY POLICY 3 DANCE LIFTS AND PARTNERING (GROUPS) 28 ELIGIBILTY VERIFCATION 4 MUSIC FORMAT 5 UNASSISTED DISMOUNTS TO THE PERFORMANCE SURFACE 28 VIDEO MEDIA POLICY 5 INJURY DURING PERFORMANCE 29 LOGO USAGE 5 DEDUCTIONS 29 CHEER LEGALITY VERIFICATION 30 GENERAL COMPETITION INFORMATION NDA SCORING PERFORMANCE AREA 7 JUDGING PANELS 31 COLLEGIATE EXPECTATIONS 7 CATEGORY DESCRIPTIONS 31 COLLEGIATE IMAGE 7 JUDGING SCALE FOR DANCE FUNDAMENTALS 32 UNIFORM 7 RANGES OF SCORES 33 MUSIC 9 DANCE GLOSSARY OF TERMS 38 CHOREOGRAPHY 9 INJURY DURING PERFORMANCE 9 NCA & NDA COLLEGE GAME DAY DIVISION ORDER OF PERFORMANCE 9 GAME DAY COLLEGE CHEER DIVISIONS OBJECTIVE 45 DIVISIONS 10 BENEFITS OF GAME DAY 45 NUMBER OF MALE PARTICIPANTS VS. FEMALE PARTICIPANTS 10 GENERAL RULES 45 TEAM ROUTINE REQUIREMENTS 10 FORMAT 46 INTERMEDIATE DIVISION RESTRICTIONS 11 45 SECOND CROWD SEGMENT 12 SKILL SCORING & RESTRICTIONS -

Shakira Arabic Dance Mp3 Download

Shakira arabic dance mp3 download Arabic Music (dance Mix). Artist: Shakira. MB · Arabic Music (dance Mix). Artist: Shakira. MB. Latest Free Shakira Belly Dance Video Free Download Mp3 Download on Mp3re tubidy, New Shakira Belly Dance Video Free Download Songs, Shakira Belly. MP3 Песни в kbps: Tony Chamoun vs Shakira - Belly (Dance music). Tony Chamoun vs Shakira - Belly (Dance music). Tony Chamoun vs Shakira. Download mp3 music: Shakira - Latino - Shakhira - Arabic Belly Dance Music. Shakira - Latino - Shakhira - Arabic Belly Dance Music. Download. Shakira. BELLY DANCE SHAKIRA MP3 Download ( MB), Video 3gp & mp4. List download link Lagu MP3 BELLY DANCE SHAKIRA ( min), last update Oct I don't want to hear her singiing in Spanish why isn't she singing in Arabic. If your going to do Arabic music. Arabic Shakira Belly Dance Ojos Asi. somnathpurkait. Loading. Arabic Music with some Arabic words with. Скачать и слушать mp3: Rai-Shakira-Arabic Belly Dance Music. Egyptian Belly Dancing - Arabic Dance Mix. shakira - Arabic music. Belly dance. Скачивайте Shakira - Belly dancing Darbakah в mp3 бесплатно или слушайте песню Шакира - Belly dancing Darbakah онлайн. Shakira Belly Dance Videos Free Download, HD Videos Free Download In Mp4, 3Gp, Flv, Mp3, HQ, p, Movies, Video Song, Trailer For free, Video. Artist: Shakira. test. ru MB · Arabic Music. Arabic - is the. Shakira Belly Dance In Dubai ﻣﻘﺎم Belly Dance Play Arabic Dance album songs MP3 by Adrian Jones and download Arabic. MAQAM طﺒﻠﺔ ﺻﻮﻟﻮ .Dubai Events - Expo - Dubai Midnight Maratho (File: 3Gp, Flv, Mp4, WBEM, Mp3). DOWNLOAD FAST DOWNLOAD PLAY Belly Dancing Tabla Mark Keys. Genre: Belly dancing Tabla solo, DJ MARK's MUSIC. -

Feminist Analysis of Belly Dance and Its Portrayal in the Media

FEMINISM IN BELLY DANCE AND ITS PORTRAYAL IN THE MEDIA Meghana B.S Registered Number 1324038 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Communication Christ University Bengaluru 2015 Program Authorized to Offer Degree Department of Media Studies ii Authorship Christ University Department of Media Studies Declaration This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a master‟s thesis by Meghana B.S Registered Number1324038 and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Committee Members: _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ Date:__________________________________ iii iv Abstract I, Meghana B.S, confirm that this dissertation and the work presented in it are original. 1. Where I have consulted the published work of others this is always clearly attributed. 2. Where I have quoted from the work of others the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations this dissertation is entirely my own work. 3. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. 4. If my research follows on from previous work or is part of a larger collaborative research project I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. 5. I am aware and accept the penalties associated with plagiarism. Date: Signature v vi Abstract Feminism in Bellydance and its portrayal in the media Meghana B.S MS in Communication, Christ University, Bengaluru Bellydance is an art form that has gained tremendous popularity in the world today. -

Corpo Hibrido: Raízes, Modernidade E Fusão No Corpo Da(O) Dançarina(O) De Tribal

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE UBERLÂNDIA – UFU INSTITUTO DE ARTES – IARTE CURSO DE GRADUAÇÃO EM DANÇA THÁSSIA CAMILA DE ALMEIDA SOARES CORPO HIBRIDO: RAÍZES, MODERNIDADE E FUSÃO NO CORPO DA(O) DANÇARINA(O) DE TRIBAL Uberlândia/MG Dezembro de 2019 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE UBERLÂNDIA – UFU INSTITUTO DE ARTES – IARTE CURSO DE GRADUAÇÃO EM DANÇA THÁSSIA CAMILA DE ALMEIDA SOARES CORPO HIBRIDO: RAÍZES, MODERNIDADE E FUSÃO NO CORPO DA(O) DANÇARINA (O) DE TRIBAL Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado como requisito para avaliação na disciplina Defesa de Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso, do Curso de Dança da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia – UFU. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Jarbas Siqueira Ramos Uberlândia/MG Dezembro de 2019 Dedico esse trabalho a minha mãe Dinamar de Almeida que com todo o amor e dedicação esteve presente em momentos relevantes durante a conclusão do meu curso. Ao meu tio Pe. Itamar de Almeida Machado a minha irmã Tatiana e irmão William. AGRADECIMENTOS Sou grata pela minha formação religiosa, pois, minha fé sempre foi o suporte para continuar perseverante e confiante durante minha trajetória acadêmica. Sou grata a minha família por sempre me apoiar, confiar e acreditar em meus sonhos, se unindo para concretizar o meu desejo de ter um espaço dedicado a dança, e de estarem sempre nos bastidores dos eventos e cuidando da logística dos meus espetáculos. À minha pequena sobrinha e futura dançarina Ana Beatriz, que durante esses dois anos e meio de convívio diário e participando diretamente comigo nas aulas do meu estúdio de dança e em tardes de estudo para a escrita desse trabalho, já despertou o interesse e o apreço pelo movimento corporal. -

2015 Full Program (PDF)

2015 Women in Dance Leadership Conference! ! October 29 - November 1, 2015! ! Manship Theatre, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA! ! Conference Director - Sandra Shih Parks WOMEN IN DANCE LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE 10/29/2015 - 11/1/2015 "1 Women in Dance Leadership Conference ! Mission Statement ! ! To investigate, explore, and reflect on women’s leadership by representing innovative and multicultural dance work to celebrate, develop, and promote women’s leadership in dance making, dance related fields, and other! male-dominated professions.! Conference Overview! ! DATE MORNING AFTERNOON EVENING Thursday 10/29/2015 !Registration/Check In! !Reception! Opening Talk -! Kim Jones/Yin Mei Karole Armitage and guests Performance Friday 10/30/2015 Speech - Susan Foster! Panel Discussions! Selected ! ! Choreographers’ Speech - Ann Dils !Master Classes! Concert Paper Presentations Saturday 10/31/2015 Speech - Dima Ghawi! Panel Discussions! ODC Dance Company ! ! ! Performance Speech - Meredith Master Classes! Warner! ! ! Ambassadors of Women Master Classes in Dance Showcase Sunday 11/1/2015 Master Class THODOS Dance Chicago Performance ! ! ! ! WOMEN IN DANCE LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE 10/29/2015 - 11/1/2015 "2 October 29th 2015! !Location 12 - 4 PM 4:30 PM - 6 PM 6 PM - 7:30 PM 8 PM - 9:30 PM !Main Theatre Kim Jones, Yin Mei ! and guests ! performance ! !Hartley/Vey ! Opening Talk by! !Studio Theatre Karole Armitage !Harley/Vey! !Workshop Theatre !Josef Sternberg ! Conference Room Jones Walker Foyer Registration! ! Conference Check In Reception Program Information! -

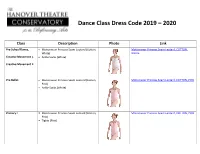

Dance Class Dress Code 2019 – 2020

Dance Class Dress Code 2019 – 2020 Class Description Photo Link Pre-School Dance, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, White) WHITE Creative Movement I, Ankle Socks (White) Creative Movement II Pre-Ballet Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, PINK Pink) Ankle Socks (White) Primary I . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, PINK Pink) . Tights (Pink) Primary II . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, Light Blue) LIGHT BLUE . Tights (Pink) Primary III . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Royal Blue) ROYAL BLUE . Tights (Pink) Teen Ballet & . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Hunter Green) HUNTER GREEN Adult Ballet II . Tights (Pink) Level A . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Fuchsia) FUCHSIA . Tights (Pink) Level B . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Bright Red) BRIGHT RED . Tights (Pink) Level C . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Maroon) MAROON . Tights (Pink) Level D, . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Black) BLACK Boys & Girls Club, . Tights (Pink) Adult Ballet Youth Ballet Company . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, (Apprentice) Butter) BUTTER . Tights (Pink) Youth Ballet Company . Any style white leotard (Junior) . Tights (Pink) Youth Ballet Company . Any style black leotard (Senior) . On the 2nd Saturday of each month any color leotard is allowed. Tights (Pink) Boys Ballet . Motionwear Cap Sleeve Fitted T-Shirt . Motionwear Mens Cap Sleeve Fitted t-shirt, (Silkskyn, White) SILKSKYN, WHITE . -

Corel Ventura

Anthropology / Middle East / World Music Goodman BERBER “Sure to interest a number of different audiences, BERBER from language and music scholars to specialists on North Africa. [A] superb book, clearly written, CULTURE analytically incisive, about very important issues that have not been described elsewhere.” ON THE —John Bowen, Washington University CULTURE WORLD STAGE In this nuanced study of the performance of cultural identity, Jane E. Goodman travels from contemporary Kabyle Berber communities in Algeria and France to the colonial archives, identifying the products, performances, and media through which Berber identity has developed. ON In the 1990s, with a major Islamist insurgency underway in Algeria, Berber cultural associations created performance forms that challenged THE Islamist premises while critiquing their own village practices. Goodman describes the phenomenon of new Kabyle song, a form of world music that transformed village songs for global audiences. WORLD She follows new songs as they move from their producers to the copyright agency to the Parisian stage, highlighting the networks of circulation and exchange through which Berbers have achieved From Village global visibility. to Video STAGE JANE E. GOODMAN is Associate Professor of Communication and Culture at Indiana University. While training to become a cultural anthropologist, she performed with the women’s world music group Libana. Cover photographs: Yamina Djouadou, Algeria, 1993, by Jane E. Goodman. Textile photograph by Michael Cavanagh. The textile is from a Berber women’s fuda, or outer-skirt. Jane E. Goodman http://iupress.indiana.edu 1-800-842-6796 INDIANA Berber Culture on the World Stage JANE E. GOODMAN Berber Culture on the World Stage From Village to Video indiana university press Bloomington and Indianapolis This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://iupress.indiana.edu Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2005 by Jane E. -

What Is Belly Dance?

What Is Belly Dance? THE PYRAMID DANCE CO. INC. was originally founded in Memphis 1987. With over 30 years Experience in Middle Eastern Dance, we are known for producing professional Dancers and Instructors in belly dancing! The company’s purpose is to teach, promote, study, and perform belly dance. Phone: 901.628.1788 E-mail: [email protected] PAGE 2 CONTACT: 901.628.1788 WHAT IS BELLY DANCE? PAGE 11 What is the belly dance? Sadiia is committed to further- ing belly dance in its various The dance form we call "belly dancing" is derived from forms (folk, modern, fusion , traditional women's dances of the Middle East and interpretive) by increasing pub- North Africa. Women have always belly danced, at lic awareness, appreciation parties, at family gatherings, and during rites of pas- and education through per- sage. A woman's social dancing eventually evolved formances, classes and litera- into belly dancing as entertainment ("Dans Oryantal " in ture, and by continuing to Turkish and "Raqs Sharqi" in Arabic). Although the his- study all aspects of belly tory of belly dancing is clouded prior to the late 1800s, dance and producing meaning- many experts believe its roots go back to the temple ful work. She offers her stu- rites of India. Probably the greatest misconception dents a fun, positive and nur- about belly dance is that it is intended to entertain men. turing atmosphere to explore Because segregation of the sexes was common in the movement and the proper part of the world that produced belly dancing, men of- techniques of belly dance, giv- ten were not allowed to be present. -

The ABDC 2021 Workshop Descriptions and Bios

The ABDC 2021 Workshop Descriptions and Instructor Bios Table of Contents below alphabetical Ahava 2 Workshop Title: All the Feels 2 Workshop Title: Classical Egyptian Technique and Combos 2 Amara 3 Workshop Title: Let’s Prepare for an Amazing Week of Dance! - Free 3 Workshop Title: Let’s Talk about Swords 3 Amel Tafsout 4 Workshop Title: Nayli Dance of the Ouled Nayl 4 Workshop Title: City Dances: Andalusian Court Dance with Scarves 6 April Rose 8 Workshop Title: Dance as an Offering 8 Arielle 9 Workshop Title: Egyptian Street Shaabi: Mahraganat Choreography 9 Athena Najat 10 Workshop Title: Oriental Roots in Anatolia: Exploring the Greek branch of the Bellydance Tree 10 Bahaia 11 WorkshopTitle: Takht & Tahmila 11 DeAnna 12 Workshop Title: Spins and Turns! 12 Devi Mamak 14 Workshop Title: Hot Rhythms, Cool Head 14 Lily 15 WorkshopTitle: Rhythms 101 15 Loaya Iris 15 WorkshopTitle: Let’s Go Pop! Modern Egyptian Style Technique and Combos. 15 Nessa 16 WorkshopTitle: Finding the Muse Within 16 Mr. Ozgen 17 WorkshopTitle: Turkish Bellydance 17 WorkshopTitle: Romani Passion 17 Roshana Nofret 18 Workshop Title: Poetry in Motion: Exquisite Arms & Hands for All Dancers 18 Stacey Lizette 19 Workshop Title: By Popular Demand: A Customized Workshop Experience Based Exploring Common Challenges 19 Ahava Workshop Title: All the Feels Date/Time: Sunday, June 27, 2021,10-12pm Central Time Workshop Description: Do you need help with stage presence? Connecting to your audiences? Courage to push through the fourth wall on stage and fully entertain a crowd? Ahava presents exercises, tips and combinations on how to emote while on stage.