Morpeth Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tour of Britain Whizzes Through Town

Issue 95 Oct/Nov 2015 Tour of Britain whizzes through town Vote for Amble! arge mble has been shortlisted for enthusiastic Aa prestigious national award crowds and could be in the running for a L greeted the Tour of share of £80,000. Britain cycle race on The Great British High Street Sept 9 as it whizzed of the Year Awards is run by the Dept of Communities and Local through Amble. Goernment. They chose Amble, Stage four of Bognor egis in Susse, and the famous tour saw restatyn in Wales as finalists in the cyclists which the Coastal Communities category. included Sir Bradley Julia Aston, director of Wiggins and Mark Amble Development Trust said Cavendish leave “We entered Amble into the Edinburgh, cycling competition, in partnership with Amble Business Club. We’re through Ford, thrilled to have been shortlisted. Wooler, Alnwick, It just strengthens our belief that Warkworth and Amble is a fantastic place to live Amble, ending at and work.” Blyth. Decorated bikes Bottom row nearest to camera is Mark Cavendish (with white shoes). Bradley Wiggins is and flags greeted net but one dark outfit, white socks. the teams as they sped up the Wynd and along Albert Street. Stage four was eventually won by 21 year old Columbian Fernando Gaviria cycling for Team Etixx Quick Step. More photos on page 14. Video and slideshow on our website. Wounded soldiers welcomed by youngsters This year’s competition saw a record applicants and now, for the first time, the public has the chance to vote directly for their best-loved high street online. -

Green Infrastructure

Wiltshire Local Development Framework Working towards a Core Strategy for Wiltshire Topic paper 11: Green infrastructure Wiltshire Core Strategy Consultation January 2012 Wiltshire Council Information about Wiltshire Council services can be made available on request in other languages including BSL and formats such as large print and audio. Please contact the council on 0300 456 0100, by textphone on 01225 712500 or by email on [email protected]. This paper is one of 16 topic papers, listed below, which form part of the evidence base in support of the emerging Wiltshire Core Strategy. These topic papers have been produced in order to present a coordinated view of some of the main evidence that has been considered in drafting the emerging Core Strategy. It is hoped that this will make it easier to understand how we have reached our conclusions. The papers are all available from the council website: Topic Paper 1: Climate Change Topic Paper 2: Housing Topic Paper 3: Settlement Strategy Topic Paper 4: Rural Signposting Tool Topic Paper 5: Natural Environment Topic Paper 6: Retail Topic Paper 7: Economy Topic Paper 8: Infrastructure and Planning Obligations Topic Paper 9: Built and Historic Environment Topic Paper 10: Transport Topic Paper 11: Green Infrastructure Topic Paper 12: Site Selection Process Topic Paper 13: Military Issues Topic Paper 14: Building Resilient Communities Topic Paper 15: Housing Requirement Technical Paper Topic Paper 16: Gypsy and Travellers Contents 1. Executive summary 1 2. Introduction 2 2.1 What is green infrastructure (GI)? 2 2.2 The benefits of GI 4 2.3 A GI Strategy for Wiltshire 5 2.4 Collaborative working 6 3. -

THE RURAL ECONOMY of NORTH EAST of ENGLAND M Whitby Et Al

THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND M Whitby et al Centre for Rural Economy Research Report THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST ENGLAND Martin Whitby, Alan Townsend1 Matthew Gorton and David Parsisson With additional contributions by Mike Coombes2, David Charles2 and Paul Benneworth2 Edited by Philip Lowe December 1999 1 Department of Geography, University of Durham 2 Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies, University of Newcastle upon Tyne Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Scope of the Study 1 1.2 The Regional Context 3 1.3 The Shape of the Report 8 2. THE NATURAL RESOURCES OF THE REGION 2.1 Land 9 2.2 Water Resources 11 2.3 Environment and Heritage 11 3. THE RURAL WORKFORCE 3.1 Long Term Trends in Employment 13 3.2 Recent Employment Trends 15 3.3 The Pattern of Labour Supply 18 3.4 Aggregate Output per Head 23 4 SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL DYNAMICS 4.1 Distribution of Employment by Gender and Employment Status 25 4.2 Differential Trends in the Remoter Areas and the Coalfield Districts 28 4.3 Commuting Patterns in the North East 29 5 BUSINESS PERFORMANCE AND INFRASTRUCTURE 5.1 Formation and Turnover of Firms 39 5.2 Inward investment 44 5.3 Business Development and Support 46 5.4 Developing infrastructure 49 5.5 Skills Gaps 53 6. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 55 References Appendices 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The scope of the study This report is on the rural economy of the North East of England1. It seeks to establish the major trends in rural employment and the pattern of labour supply. -

2001 Census Report for Parliamentary Constituencies

Reference maps Page England and Wales North East: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 42 North West: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 43 Yorkshire & The Humber: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 44 East Midlands: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 45 West Midlands: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 46 East of England: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 47 London: County & Parliamentary Constituencies 48 South East: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 49 South West: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 50 Wales: Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 51 Scotland Scotland: Scottish Parliamentary Regions 52 Central Scotland Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 53 Glasgow Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 54 Highlands and Islands Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 55 Lothians Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 56 Mid Scotland and Fife Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 57 North East Scotland Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 58 South of Scotland Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 59 West of Scotland Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 60 Northern Ireland Northern Ireland: Parliamentary Constituencies 61 41 Reference maps Census 2001: Report for Parliamentary Constituencies North East: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies Key government office region parliamentary constituencies counties -

Ethnicity in the North East an Overview

EthnicityNORTH EAST Ethnicity in the North East an overview NORTH EAST ASSEMBLY THE VOICE FOR THE REGION Ethnicity in the Acknowledgements North East I would like to acknowledge the help and guidance received from everyone I have contacted while compiling this guidance. I am particularly indebted to the staff of the Home Office Drugs Prevention Advisory Service, particularly Robert Martin Government Office for the North East and Deborah Burns and Karen Kirkbride, for their continuous support, advice and encouragement. Veena Soni Diversity Advisor Drugs Prevention Advisory Service 1 Ethnicity in the Foreword by Angela Eagle North East The Home Office has committed itself to promoting race equality, particularly in the provision of public services such as education, health, law and order, housing and local government; and achieve representative workforces in its services areas. We are also working hard to promote cohesive communities and deal with the issues that cause segregation in communities. One of the Home OfficeÕs seven main aims is to support strong and active communities in which people of all races and backgrounds are valued and participate on equal terms by developing social policy to build a fair, prosperous and cohesive society in which everyone has a stake. To work with other departments and local government agencies and community groups to regenerate neighbourhoods, to support families; to develop the potential of every individual; to build the confidence and capacity of the whole community to be part of the solution; and to promote good race and community relations, combating prejudice and xenophobia. To promote equal opportunities both within the Home Office and more widely and to ensure that active citizenship contributes to the enhancement of democracy and the development of civil society. -

Community Research in Castle Morpeth Borough Council Area 2003

Community Research in Castle Morpeth Borough Council Area 2003 Research Study Conducted for The Boundary Committee for England October 2003 Contents Introduction 1 Executive Summary 4 Local Communities 6 Defining Communities 6 Identifying Communities 6 Identity with the Local Community in the Castle Morpeth Borough Council Area 7 Overall Identity 7 Effective Communities 9 Involvement 13 Affective Communities 16 Bringing Effective and Affective Communities Together 17 Local Authority Communities 19 Belonging to Castle Morpeth Borough Council Area 19 Belonging to Northumberland County Council Area 22 Knowledge and Attitudes towards Local Governance 25 Knowledge of Local Governance 25 Involvement with Local Governance 26 Administrative Boundary Issues 26 Appendices 1. Methodology – Quantitative 2. Methodology - Qualitative 3. Sub-Group Definitions 4. Place Name Gazetteer 5. Qualitative Topic Guide 6. Marked-up Questionnaire Community Research in Castle Morpeth Borough Council Area 2003 for The Boundary Committee for England Introduction Research Aims This report presents the findings of research conducted by the MORI Social Research Institute on behalf of The Boundary Committee for England (referred to in this report as "The Committee") in the Castle Morpeth Borough Council area. The aim of this research is to establish the patterns of community identity in the area. Survey Coverage MORI has undertaken research in all 44 two-tier district or borough council areas in the North East, North West and Yorkshire and the Humber regions. The research covers two-tier local authority areas only; the results may however identify issues which overlap with adjacent areas. Reports and data for other two-tier areas are provided under separately. -

Nobthullberland

162 MORPETP. NOBTHUllBERLAND. 'there we1'E! 'tS monk!, snd revenues estimated at [,100 M'a the kennels of the MOl'peth tfY.I-b(lltnag, whicb hunt-two the buildings appear to have been then almost entirely; days a week (TuelldaysandSatu1'days)jJ. BlenCQweCookson destroyed, and nothing now remains standing above ground as<}. is the present master: Morpeth and Newcastle are een. except the 15th eentury north doorway of the clmrch; but vanient places for hunting visItors.. The principal land. 60 far all has been ascertained the general plan was almost owner is Andrew John B1ackett-Ord esq. of Whittield Hall. identictr.l with tha.t of Fountains, and very simila.r in The acreage is 115 of good land, ornamentedwithfine wood l dimensions I about 1870, Mr. Woodman, of Morpeth, made rateable value, £1,559; the population in 1 891 was 114. some exca.vatiom, on the site of the Chapter honse, and met Tranwell and High Church form one township in with portions of the vaulting ribs and several fine examples the parish and union of Morpetb, western division of Castle af capitals of the Transition period; the floor was found to ward. High Church, on 1& bold eminence about half a. mile ha.ve been laid with small black and red tiles, and fragments from Morpeth, contains the parish I:hurch, the rectory of ruby glass were discovered amongst the rubbish: in 1878, house, and several residences, having ample gardens in a further exa.mination of this spot led to the recovel'Y of front tastefully laid out. -

The London Gazette, 26Th February 1976 2953

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 26TH FEBRUARY 1976 2953 A copy of the Order and the map contained in it has SELBY DISTRICT COUNCIL been deposited and may be inspected free of charge at NOTICE OF CONFIRMATION OF PUBLIC PATH ORDER the office of the Secretary of Huntingdon District Council, County Buildings, Huntingdon during normal office hours. HIGHWAYS ACT, 1959 Any representation or objection with respect to the COUNTRYSIDE ACT, 1968 Order may be sent in writing to the office of the Secretary, The District Council of Selby (Parish of Lead—Bridlepath Huntingdon District Council, County Buildings, Hunting- No. 1) Public Path Diversion Order No. 2, 1975 don before the 9th April 1976, and should state the grounds upon which it is made. Notice is hereby given that on the 13th February 1976 If no representation or objection are duly made, or if the District Council of Selby confirmed the above-named any so made are withdrawn the Huntingdon District Order. Council may instead of submitting the Order to the Secre- The effect of the Order as confirmed is to divert the tary of State for the Environment themselves confirm the public right of way running from the Crooked Billet and Order. If the Order is submitted to the Secretary of State along the drive way to Leadhall Farmhouse to a line running any representations and objections which have been duly parallel to the existing right of way on the eastern side made and not withdrawn will be transmitted with the of the fence to the grounds of Leadhall Farmhouse. Order. A copy of the Order as confirmed and the map contained in it has been deposited and may be inspected free of Dated 13th February 1976. -

Morpeth-Bedlington-Ashington

TECHNICAL REPORT WA/90/14 Geology and land-use planning: Morpeth-Bedlington-Ashington Part 1 LAND-USEPLANNING I Jackson and D J D Lawrence This report has been generated from a scanned image of the document with any blank pages removed at the scanning stage. Please be aware that the pagination and scales of diagrams or maps in the resulting report may not appear as in the original BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY TECHNICAL REPORT WA/90/14 Onshore Geology Series Geology and land-use planning: Morpeth-Bedlington-Ashington Part 1 LAND-USEPLANNING 1:25 000 sheets NZ28 andNZ 38 Parts of 1:50000 geological sheets 9 (Rothbury), 10 (Newbiggin), 14 (Morpeth) and 15 (Tynemouth) I Jackson and D J D Lawrence This study was commissioned by the Department of the Environ- ment, but the views expressed in it are not necessarily those of the Department Maps and diagrams in this book use topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping Geographical index UK, England, Northumberland Subject index Land-use planning, thematic maps, resources, mining, engin- eering geology, Quaternary, Carboniferous Bibliographic reference Jackson, I, and Lawrence, D J D. 1990. Geology and land- use planning: Morpeth- Bedlington-Ashington. Part 1: Land-use planning. British Geological Survey Technical Report WA/90/14 0 NERC copyright 1990 Keyworth,Nottingham British Geological Survey1990 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available through the Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Keyworth, Murchison House, Edinburgh, and at Plumtree (06077) 6111 Telex378173 BGSKEY G the BGS London Information Office in the Geological Museum. Fax 06077-6602 The adjacent Geological Museum bookshop stocks the more popular books for sale over the counter. -

2000 No. 2490 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

0 R STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2000 No. 2490 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The County of Northumberland (Electoral Changes) Order 2000 Made---- 11th September 2000 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) and (3) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated November 1999 on its review of the county of Northumberland together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(b) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the County of Northumberland (Electoral Changes) Order 2000. (2) This article and articles 2 and 5 shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 3rd May 2001, on 10th October 2000; (b) for all other purposes, on 3rd May 2001. (3) Articles 3 and 4 of this Order shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election of a parish councillor for the parish of Hexham or Morpeth on 1st May 2003, on 10th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. (4) In this Order— “county” means the county of Northumberland; “existing”, in relation to a division or ward, means the division or ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; (a) 1992 c. -

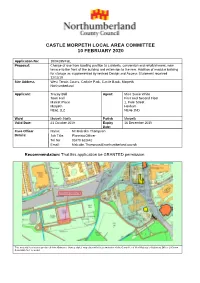

Castle Morpeth Local Area Committee 10 February 2020

CASTLE MORPETH LOCAL AREA COMMITTEE 10 FEBRUARY 2020 Application No: 19/04195/FUL Proposal: Change of use from bowling pavilion to cafeteria, conversion and refurbishment, new terrace to the front of the building and extension to the rear. Addition of modular building for storage as supplemented by revised Design and Access Statement received 12/11/19 Site Address West Tennis Courts, Carlisle Park, Castle Bank, Morpeth Northumberland Applicant: Tracey Bell Agent: Miss Susie White Town Hall First And Second Floor Market Place 1, Fore Street Morpeth Hexham NE61 1LZ NE46 1ND Ward Morpeth North Parish Morpeth Valid Date: 21 October 2019 Expiry 16 December 2019 Date: Case Officer Name: Mr Malcolm Thompson Details: Job Title: Planning Officer Tel No: 01670 622641 Email: [email protected] Recommendation: That this application be GRANTED permission This material has been reproduced from Ordnance Survey digital map data with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright (Not to Scale) 1. Introduction 1.1 This application is being reported to the Local Area Committee as the proposal has been submitted on behalf of Morpeth Town Council and relates to land owned by Northumberland County Council. 2. Description of the Proposals 2.1 The application seeks planning permission for refurbishment and a change of use of the existing bowling pavilion situated within Carlisle Park to a cafeteria along with the following: - minor alterations to elevations; - provision of new terrace to front; - small extension upon rear; and - siting of portable office/store to rear. 2.2 The application has been submitted following the earlier submission of a pre-application enquiry when a favourable response was offered. -

Morpeth (MPT).Indd 1 11/10/2018 10:42

Morpeth Station i Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local area map Rail replacement buses will depart from the front of the station Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at August 2018) BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS DESTINATION DESTINATION DESTINATION ROUTES STOP ROUTES STOP ROUTES STOP Acklington Village ^ X18 D 43 B Red Row X18 D Gosforth X14, X15, X16#, Alnwick X15, X18 D C 43 B X18 Regent Centre (Gosforth) X14, X15, X16#, Amble by-the-sea X18 D Guide Post 2 B C X18 Annitsford 43 B S2 E Rothbury X14 D Hepscott Park Ashington 35 Bus Station 43 B Shilbottle X15 D HMPS Northumberland Bebside 2 B X18 D Stannington S1, S2 C (Acklington) Bedlington 2, 43 B Kirkhill X16 D 2, 43 B { Stobhill Bedlington Station 2 B { Lancaster Park X14, X15 D T1C E Belford X15#, X18 D Longframlington X14 D St Mary's S1, S2 E Berwick-upon-Tweed ^ X15#, X18 D Longhorsley X14 D Thropton X14 D Blyth 2 B 2, 43 A Ulgham X18 D S2, X14, X15, Broomhill X18 D { Morpeth Town Centre (Bus Station) D Warkworth X18 D X16, X18 Choppington 2 B S1, T1C E Widdrington Village ^ X18 D X14, X15, X16#, C Woodhorn 35 Bus Station X18 Newbiggin 35 Bus Station Clifton S1 E 43 B Newcastle Upon Tyne ^ X14, X15, X16#, Notes Cowpen 2 B C X18 Cramlington ^ 43 B Services S1, S2 and T1C operate limited Mondays to Saturdays { Northumberland County Hall X14 C services only.