Animating the Science Fiction Imagination Ii Animating the Science Fiction Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Animation History Ebook

FRENCH ANIMATION HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Neupert | 224 pages | 03 Mar 2014 | John Wiley & Sons Inc | 9781118798768 | English | New York, United States French Animation History PDF Book Messmer directed and animated more than Felix cartoons in the years through This article needs additional citations for verification. The Betty Boop cartoons were stripped of sexual innuendo and her skimpy dresses, and she became more family-friendly. A French-language version was released in Mittens the railway cat blissfully wanders around a model train set. Mat marked it as to-read Sep 05, Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. In , Max Fleischer invented the rotoscope patented in to streamline the frame-by-frame copying process - it was a device used to overlay drawings on live-action film. First Animated Feature: The little-known but pioneering, oldest-surviving feature-length animated film that can be verified with puppet, paper cut-out silhouette animation techniques and color tinting was released by German film-maker and avante-garde artist Lotte Reiniger, The Adventures of Prince Achmed aka Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed , Germ. Books 10 Acclaimed French-Canadian Writers. Rating details. Dave and Max Fleischer, in an agreement with Paramount and DC Comics, also produced a series of seventeen expensive Superman cartoons in the early s. Box Office Mojo. The songs in the series ranged from contemporary tunes to old-time favorites. He goes with his fox terrier Milou to the waterfront to look for a story, and finds an old merchant ship named the Karaboudjan. The Fleischers launched a new series from to called Talkartoons that featured their smart-talking, singing dog-like character named Bimbo. -

A History of Aeronautics

A History of Aeronautics E. Charles Vivian A History of Aeronautics Table of Contents A History of Aeronautics..........................................................................................................................................1 E. Charles Vivian...........................................................................................................................................1 FOREWORD.................................................................................................................................................2 PART I. THE EVOLUTION OF THE AEROPLANE...............................................................................................2 I. THE PERIOD OF LEGEND......................................................................................................................3 II. EARLY EXPERIMENTS.........................................................................................................................6 III. SIR GEORGE CAYLEY−−THOMAS WALKER................................................................................16 IV. THE MIDDLE NINETEENTH CENTURY.........................................................................................21 V. WENHAM, LE BRIS, AND SOME OTHERS......................................................................................26 VI. THE AGE OF THE GIANTS................................................................................................................30 VII. LILIENTHAL AND PILCHER...........................................................................................................34 -

In the Nature of Cities: Urban Political Ecology

In the Nature of Cities In the Nature of Cities engages with the long overdue task of re-inserting questions of nature and ecology into the urban debate. This path-breaking collection charts the terrain of urban political ecology, and untangles the economic, political, social and ecological processes that form contemporary urban landscapes. Written by key political ecology scholars, the essays in this book attest that the re- entry of the ecological agenda into urban theory is vital, both in terms of understanding contemporary urbanization processes, and of engaging in a meaningful environmental politics. The question of whose nature is, or becomes, urbanized, and the uneven power relations through which this socio-metabolic transformation takes place, are the central themes debated in this book. Foregrounding the socio-ecological activism that contests the dominant forms of urbanizing nature, the contributors endeavour to open up a research agenda and a political platform that sets pointers for democratizing the politics through which nature becomes urbanized and contemporary cities are produced as both enabling and disempowering dwelling spaces for humans and non-humans alike. Nik Heynen is Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Maria Kaika is Lecturer in Urban Geography at the University of Oxford, School of Geography and the Environment, and Fellow of St. Edmund Hall, Oxford. Erik Swyngedouw is Professor at the University of Oxford, School of Geography and the Environment, and Fellow of St. Peter’s College, Oxford. Questioning Cities Edited by Gary Bridge, University of Bristol, UK and Sophie Watson, The Open University, UK The Questioning Cities series brings together an unusual mix of urban scholars under the title. -

Nationalism, the History of Animation Movies, and World War II Propaganda in the United States of America

University of Akureyri Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Modern Studies 2011 Intersections of Modernity: Nationalism, The History of Animation Movies, and World War II propaganda in the United States of America Kristján Birnir Ívansson Final BA Thesis in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Akureyri Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Modern studies 2011 Intersections of Modernity: Nationalism, The History of Animation Movies, and World War II propaganda in the United States of America Kristján Birnir Ívansson A final BA Thesis for 180 ECTS unit in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Instructor: Dr. Giorgio Baruchello Statements I hereby declare that I am the only author of this project and that is the result of own research Ég lýsi hér með yfir að ég einn er höfundur þessa verkefnis og að það er ágóði eigin rannsókna ______________________________ Kristján Birnir Ívansson It is hereby confirmed that this thesis fulfil, according to my judgement, requirements for a BA -degree in the Faculty of Hummanities and Social Science Það staðfestist hér með að lokaverkefni þetta fullnægir að mínum dómi kröfum til BA prófs í Hug- og félagsvísindadeild. __________________________ Giorgio Baruchello Abstract Today, animations are generally considered to be a rather innocuous form of entertainment for children. However, this has not always been the case. For example, during World War II, animations were also produced as instruments for political propaganda as well as educational material for adult audiences. In this thesis, the history of the production of animations in the United States of America will be reviewed, especially as the years of World War II are concerned. -

Nostalgia, Transgression, and Capitalism at the Virginia State Fair, 1946-1976

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2012 "What is the Best and Most Typical": Nostalgia, Transgression, and Capitalism at the Virginia State Fair, 1946-1976 Sarah Stanford-McIntyre College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Stanford-McIntyre, Sarah, ""What is the Best and Most Typical": Nostalgia, Transgression, and Capitalism at the Virginia State Fair, 1946-1976" (2012). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626677. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-hx5j-6g94 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “What is best and most typical” Nostalgia, Transgression, and Capitalism at the Virginia State Fair 1946-1976 Sarah Stanford-Mclntyre Amarillo, TX Bachelors of Arts, University of Texas at Austin, 2009 Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary May 2012 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts A f\X x Sarah Stanford-Mclntyre Approved py the ffiorrymit/deTDecernber 2011 Committee Chair Tofessor Arthur Knight The College of William & Mary Processor Charlie McGovern The College of Wiliam & Mary L Professor Kara Thompson The College of Wiliam & Mary ABSTRACT PAGE In this thesis I contextualize the mid-twentieth century State Fair of Virginia as an event both steeped in local tradition and fundamentally affected by the national cultural and political climate. -

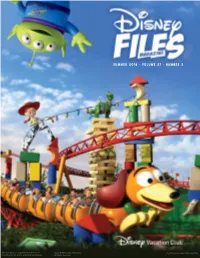

Summer 2018 • Volume 27 • Number 2

Summer 2018 • Volume 27 • Number 2 Slinky® Dog is a registered trademark of Jenga® Pokonobe Associates. Toy Story characters ©Disney/Pixar Poof-Slinky, Inc. and is used with permission. All rights reserved. WeLcOmE HoMe Leaving a Disney Store stock room with a Buzz Lightyear doll in 1995 was like jumping into a shark tank with a wounded seal.* The underestimated success of a computer-animated film from an upstart studio had turned plastic space rangers into the hottest commodities since kids were born in a cabbage patch, and Disney Store Cast Members found themselves on the front line of a conflict between scarce supply and overwhelming demand. One moment, you think you’re about to make a kid’s Christmas dream come true. The next, gift givers become credit card-wielding wildebeest…and you’re the cliffhanging Mufasa. I was one of those battle-scarred, cardigan-clad Cast Members that holiday season, doing my time at a suburban-Atlanta mall where I developed a nervous tick that still flares up when I smell a food court, see an astronaut or hear the voice of Tim Allen. While the supply of Buzz Lightyear toys has changed considerably over these past 20-plus years, the demand for all things Toy Story remains as strong as a procrastinator’s grip on Christmas Eve. Today, with Toy Story now a trilogy and a fourth film in production, Andy’s toys continue to find new homes at Disney Parks around the world, including new Toy Story-themed lands at Disney’s Hollywood Studios (pages 3-4) and Shanghai Disneyland (page 22). -

![Walt Disney Treasures - the Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit [2 DVD] Walt Disney Treasures - the Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit [2 DVD]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4309/walt-disney-treasures-the-adventures-of-oswald-the-lucky-rabbit-2-dvd-walt-disney-treasures-the-adventures-of-oswald-the-lucky-rabbit-2-dvd-2964309.webp)

Walt Disney Treasures - the Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit [2 DVD] Walt Disney Treasures - the Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit [2 DVD]

Walt Disney Treasures - The Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit [2 DVD] Walt Disney Treasures - The Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit [2 DVD] Treasures-serien fortsetter sin imponerende dokumentasjon over Disneys samlede verker. Denne gangen dykkes det 80 år tilbake i tid - til en tid før selv Mikke Mus var ensbetydende med Disney. The Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit Walt Disney Robert Winkler Productions 1927-1928 Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment 4:3 fullskjerm (1,33:1) Dolby Digital 2.0, 5.1 172 min. 2 7 Og husk. Alt startet med en? kanin. For kaninen kom før musa. The Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit har dermed sin rettmessige plass i Disneys skattkammerserie, Walt Disney Treasures. Vi skal imidlertid la historien ligge et avsnitt, og stille et annet spørsmål: Holder Oswald mål som underholdning anno 2009? For å teste dette innkalte jeg hjelp fra mitt lokale testpanel. Irma (9), Aksel (7), Felix (snart 2). Sammen representerer de et bredt smaksspekter som favner fra Winx og SvampeBob til Sauen Shaun (eller Bææ). Dette er over åtti år gamle filmer. I svart-hvitt. Til tider i ganske dårlig forfatning med riper og slitasje som selv ikke nitidig restaurering kan skjule. Selv om entusiastene kan glede seg over den kunstferdige animasjonen, er den enkel. Til tider minimalistisk på grensen til det abstrakte. Likevel sitter testpanelet og vrir seg i latter. Hva er det vi ler av? Tjukke, lodne menn. Dyr som fungerer som alt fra spilledåser til spretterter. Oswald som bruker ørene sine som fluesmekker for å holde styr på de ustyrlige pølsene som forsøker å stikke av fra pølseboden hans. -

Celebrations-Issue-23-DV24865.Pdf

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World Issue 23 Spaceship Earth 42 Contents all year long with Letters ..........................................................................................6 Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News & Updates................................................10 Celebrations MOUSE VIEWS ......................................................... 15 Guide to the Magic Disney and by Tim Foster............................................................................16 Conservation 52 Explorer Emporium magazine! by Lou Mongello .....................................................................18 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................20 Receive 6 issues for Photography Tips & Tricks by Tim Devine .........................................................................22 $29.99* (save more than Interview with Pin Trading & Collecting 56 by John Rick .............................................................................24 15% off the cover price!) Ridley Pearson Disney Cuisine by Allison Jones ......................................................................26 *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United Travel Tips States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. by Beci Mahnken ...................................................................28 Disneyland Magic Oswald the by J Darling...............................................................................30 Lucky Rabbit -

Technograph5919441945cham.Pdf

L I E> I^ARY OF THE U N IVLRSITY or ILLINOIS G20.5 TH ..59 AtTGF'^HAl-t STA6«S' o^ ,^ .<o ^# -^i^cc;*'/ rH Juuiuv m, iiLk iiiE last link in the 10-mile Shasta Dam convey- The Convejnr Co. 32«u E. Slauson ilvenu* lo9 Angeles, CdliTeml* in"; system is a mile and a half unit made by the Atteotloni Ur. U.S.Saxo, Prasi^ent, Conveyor Company of Los Angeles, using 17,500 New As joa toiDH, our use of tho trougtilng cor.voTor system at Sh&sta D&3 using NeM ijepsrture CoavoTor EtoU bearings and Installed by your cospai)/, Departure Self-Sealed Ball Bearings of two types. ^3 about Goopleted. '.;hen this Job was being discussed at the start, m questlonod ttm u» of Mew Departure Sealed Conveyor bearings in service on ^6 inctt belts For nearly four years this system has handled 13 Carrying six inch rock at 1,50 feet per lUnute, Considering that even ii; the building of uouldor Jan h« had not hii as large a conveyor problea, »« mre raluctant to experliMnt any aor* than ii« million tons of rock as big as 6 inches in diameter. hbd to In designing equip.unt for Shasta Dam. l^oH, after nearly four years irlth extreioely low and satisfactory .^'i> tenance costs, appraxiastely 13|0>M,C>^ tons hav« been handled vrith this The satisfactory service obtained is proof that these c^ulpnent. tie know that the greatest savljig In the use of thta deili^ ma In t^ft self-sealed "Lubricated-for-life" ball bearings are not alialnation of lubricAtins and of cleaning up after lubricating, uada possible by the use of sealed bearings. -

Heritage an Independent Producer, Creative Director and Writer

A multi-time Member Cruise presenter and longtime friend to Disney Vacation Club, David A. Bossert is a celebrated artist, filmmaker and author. The 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company is now heritage an independent producer, creative director and writer. Also a noted historian, Bossert is a respected authority and expert on the history of Disney animation. He is a member of the CalArts Board of Trustees and is a visiting scholar at Carnegie Mellon University’s Entertainment Technology Center (ETC) in Pittsburgh. Bossert co-authored Disney Animated, which was named iPad App of 2013 by Apple and won a prestigious British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) award. His new Oswald fans in luck book, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons, is published by Disney Definitive new book marks character’s 90th anniversary Editions. Learn more about the author online at davidbossert.com. By Dave Bossert Like many Disney fans, I was very aware Just as I finished reading that article, my Oswald cartoons are 90 years old, they have a that Oswald the Lucky Rabbit was an early and e-mail chimed with an incoming message freshness to them that defies their age because popular animated character that eventually from my then bosses at the studio. They had of those inventive animation gags. faded into obscurity. Eclipsed by the popularity forwarded an e-mail from someone inquiring The other aspect that I found intriguing of Mickey Mouse, Oswald went through several about the Disney-created Oswald cartoons. At about Oswald was the fact that half of the 26 design changes and by 1938 Universal, stopped that serendipitous moment, the planets seemed Walt Disney-created cartoons were missing— making cartoons starring that rambunctious to have aligned just right for the Oswald the completely lost with no apparent film prints rabbit. -

ȯlj¹Â·È¿ªå

è¯ ç‰¹Â·è¿ªå£«å°¼ 电影 串行 (大全) Alice's Day at https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/alice%27s-day-at-sea-2836486/actors Sea Alice's Orphan https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/alice%27s-orphan-2836505/actors Alice's Spanish https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/alice%27s-spanish-guitar-2836503/actors Guitar Alice Chops the https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/alice-chops-the-suey-2836551/actors Suey Alice Loses Out https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/alice-loses-out-2836606/actors The Plow Boy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-plow-boy-1137742/actors The Opry https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-opry-house-1137749/actors House The Karnival https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-karnival-kid-1137756/actors Kid Alice in the Big https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/alice-in-the-big-league-16038954/actors League Alice's https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/alice%27s-wonderland-2078203/actors Wonderland The Barn https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-barn-dance-2275783/actors Dance The Matinee https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-matinee-idol-2288328/actors Idol Little Red https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/little-red-riding-hood-2381354/actors Riding Hood The Skeleton https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-skeleton-dance-2531855/actors Dance Minnie's Yoo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/minnie%27s-yoo-hoo-26197405/actors Hoo Africa Before https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/africa-before-dark-2826146/actors Dark Alice's Brown -

Musik Im Animationsfilm: Arbeitsbibliographie Zusammengestellt Von Hans J

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Ludger Kaczmarek; Hans Jürgen Wulff; Matthias C. Hänselmann Musik im Animationsfilm: Arbeitsbibliographie 2016 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12799 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kaczmarek, Ludger; Wulff, Hans Jürgen; Hänselmann, Matthias C.: Musik im Animationsfilm: Arbeitsbibliographie. Westerkappeln: DerWulff.de 2016 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 164). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12799. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0164_16.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 164, 2016: Musik im Animationsfilm Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Ludger Kaczmarek u. Hans J. Wulff. ISSN 2366-6404. URL: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0164_16.pdf Letzte Änderung: 12.1.2016. Musik im Animationsfilm: Arbeitsbibliographie Zusammengestellt von Hans J. Wulff und Ludger Kaczmarek Mit einer Einleitung von Matthias C. Hänselmann: Phasen und Formen der Tonverwendung im Animationsfilm* Der Animationsfilm ist ein von Grund auf syntheti- die lange Zeit dominante Animationsform handelt, sches Medium: Alle visuellen Aspekte – und das 2) gerade der Zeichentrickfilm Prinzipien der anima- wird besonders am Zeichentrickfilm deutlich – müs- tionsspezifischen Musikverwendung hervorgebracht sen zunächst künstlich erzeugt werden. Es müssen hat und diese Prinzipien 3) dann auch von anderen Serien syntagmatisch kohärenter Bewegungsphasen- Animationsfilmformen übernommen wurden bzw.