Mamluk Studies Review, Vol. XVII (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Msr Xviii, 2013

Composition and Worldview of some Bourgeois and Petit-Bourgeois Mamluk Adab-Encylopedias Thomas Herzog Thomas Herzog Bern University Composition and Worldview of some Bourgeois and Petit-Bourgeois Mamluk Adab-Encylopedias The economic and cultural rise of parts of the ʿāmmah 1 due to the particular economic and infrastructural conditions of the Mamluk era brought with it the emergence of new intermediate levels of literature that were situated between Mamluk Adab-Encylopedias the literature of the elite and that of the ignorant and unlettered populace; be- tween the Arabic koiné (al-ʿarabīyah al-fuṣḥá) and the local dialects (ʿāmmīyahs); and between written and oral composition, performance, and transmission. The following article proposes to analyze the composition of three Mamluk adab- encyclopedias and compendia and their treatment of poverty and wealth in light of the social milieus of their authors and audiences. The Rise of a New Class When the Mamluks took power between 1250 and 1260 in the former Ayyubid lands of Egypt and Syria, the Mongol invasions and the assassination of the Ab- basid caliph in Baghdad as well as the ongoing Crusader presence in Palestine all brought about a shift in the eastern Islamic world’s center to Mamluk Egypt, which became a highly effective bulwark of Arab-Islamic rule and culture. The © The Middle East Documentation Center. The University of Chicago. This article is the enhanced version of a contribution first presented as a “Working Paper” at the Annemarie Schimmel Kolleg for the History and Society during the Mamluk Era, Bonn, Ger- many. I would like to thank Nefeli Papoutsakis, Münster, for her most valuable remarks on the translation of some Arabic terms. -

Contents 3 4 7 9 10 13 14 15 18 Dear Map Friends

Newsletter N°17, September 2003 Contents Dear Map Friends, Pictures at The Autumn season start off with a visit to Johan Van Volsem's 3 extensive map collection, in Halle, which is about 20 km south west of an Exibition Brussels. Apart from the details in our Newsletter, you will find a registration form enclosed. Our second BIMCC event is our 5th Study Looks at Books Session on 13 December 2003, this time focussed on "Plans of (I and II) 4 Towns and Fortified Places", which will take place at College St Michel, near Square Montgomery, Brussels. We would appreciate A brief look that you return your registration forms for both events as early as at 2 Books 7 possible. In this context, may we remind you that the exhibition of Brussels' development in the Town Hall, with maps and charts, has BIMCC been extended until 31 December 2004 (cf our Exhibitions section). th 9 5 AGM Other BIMCC connected events are detailed in International News; let me tell you that Wulf Bodenstein will give a talk on Zanzibar in the 19th International Century from the cartographic point of view at the Comité Français de News & Events 10 Cartographie's Study Day in Paris on 5 November 2003. On 14/15 November, the 2nd Paris Map Fair will be held in the Hotel Ambassador; the BIMCC, which participated last year, will again have Maps on Cows 13 a stand at this significant international event. Nearer home, the 5th Breda Map Fair will take place on 28/29 November, which will be th followed by the 12 Antiquarian Book Fair, in Mechelen, 12/14 BIMCC News December 2003; interestingly, at Mechelen, there will be a free 14 valuation of books and maps on Saturday, 13 December between 11am and 1 pm. -

'The Medieval Housebook and Elias's “Scenes from the Life of a Knight”: a Case

1 2 Published by The Norbert Elias Foundation J.J. Viottastraat 13 1017 JM Amsterdam Board: Johan Goudsblom, Herman Korte Stephen Mennell Secretary to the Foundation: EsterWils Tel: & Fax: +31 20 671 8620 Email: [email protected] http://norberteliasfoundation.nl/ Free eBook 2015 http://www.norberteliasfoundation.nl/docs/pdf/Medievalhousebook.pdf Printed by the University of Leicester 3 The Medieval Housebook and Elias’s ‘Scenes from the Life of a Knight’: A case study fit for purpose? Patrick Murphy Contents1 Part 1: The Elias thesis in outline 1. Introduction 2. Why was Elias attracted to The Medieval Housebook? 3. Elias’s selection and interpretation of the drawings Part 2: Elias as a point of departure 4. Focus on the artist, with the patron in absentia 5. A presentational farrago 6. A possible case of intellectual amnesia Part 3: Moving beyond Elias 7. An overview of the housebook figuration 8. Naming the manuscript: Its appearance and form 9. What’s in a picture? Attribution and interpretation 10. Reconstituting the housebook: Problems and pitfalls 11. Is it a book? 12. The precious, the mundane and the commonplace Part 4: Moving further beyond Elias 13. Elusive timelines 14. Excurses on Swabia in the later Middle-Ages 15. Backwater or whirlpool: Aggressive resentment or nostalgia? 16. The quest to identify the Master 17. From Master to patron 18. In search of Elias’s benchmarks Part 5: Climbing out on a limb 19. Artistic empathy or, could it be ridicule? Part 6: Conclusion 20. Were the housebook drawings fit for purpose? 21. Involvement -

Euriskodata Rare Book Series

v&tabtxm imtij jKpedal relation to Üjtix wcdg mrtagrapljkal ftejrrmniafimt WzMM Wsm <ww%%. Wi> WM — THE DISCOVERIES THE NORSEMEN IN AMERICA ~zs&=z^^ V Title-page of the Wolfegg Ptolemy Manuscript. (V2 the actual size, i. e. ty scale.) H/Snn ÖDljc JXnraancn m America ittitlj »penal relation to tijm taxi]} cartojjrajrffiral Jtepreaentatimt 'V By JOSEPH FISCH E R S. J. Professor of Geography Jesuit College Feldkirch Austria Üüranslrttcö from tlje (German By BASIL H. SOULSBY B. A. Superintendent of the Map Room British Museum Hon. Sec. of the Halduyt Society LONDON HENRY STEVENS, SON & STILES 39 Great Russell Street over against the South-West Corner of the British Museum st. louis : b. herder 1 7 south broadway I9O3 Bibliographia, quasi stillae de arbore scientiae manantes collectae et ad conservandum asportatae. PREFACE HE " Antiquitates Americana*/ 1 that epoch- making work by Carl Chr. Kafn (1837), has now for over sixty years enjoyed a decided influence in the answer to the question — " What did the Norsemen dis- cover in America?" Raft] seemed to have a complete mastery of all the Norse literature bearing on the subject, and it is quite intelligible that many peculiar dicta should have been accepted, merely on his authority, though subsequent in- vestigations have proved them unsound. The followers of Rafn were numerous and uncritical, and went much further than their master. Some of the arguments, which he employed merely as a secondary support to his theories, were twisted by them and described as incontestable and indisputable evidence. 1 Such a breach of all laws of criticism did not fail to arouse a storm of opposition. -

The Italian Map Trade, 1480–1650 David Woodward

STATE CONTEXTS OF RENAISSANCE MAPPING 31 • The Italian Map Trade, 1480–1650 David Woodward The story of the Italian map trade mirrors the trends in attended a lecture in Venice, he was listed among the au- general European economic history in the sixteenth cen- dience as “Franciscus Rosellus florentinus Cosmogra- tury, of which one major force was a shift from a Medi- phus.” Marino Sanuto also lauded him as a cosmographer terranean to an Atlantic economy. During the first part of in an epigram in his Diaries. Several important maps are the period covered by this chapter, from 1480 to 1570, known from his hand from at least the 1490s.3 But a re- the engravers, printers, and publishers of maps in Flor- cent study may put his cartographic activity back a decade ence, Rome, and Venice dominated the printed map earlier: Boorsch has surmised, on stylistic grounds, that trade. More maps were printed in Italy during that period than in any other country in Europe.1 After 1570, a pe- riod of stagnation set in, and the Venetian and Roman Abbreviations used in this chapter include: Newberry for the New- berry Library, Chicago. sellers could no longer compete with the trade in Antwerp 1. For a useful map comparing the centers of printed world map pro- and Amsterdam. This second period is characterized by duction in Europe in 1472–1600 with those in 1600 –1700, showing the reuse of copperplates that had been introduced in the the early dominance of the Italian states, see J. B. Harley, review of The sixteenth century. -

Table of Contents

A Journal of the MAp o GEOGRAPHY Rou 0 TABLE OF THE AMERIC LIBRARY Asso LATlO 0.9 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURES Worlds Apart: ative American World Views in the Age of Discovery 5 by LOllis DeVorsey, Jr. Columbus Considered: A Selected Bibliography of Recently Published Materials About Christopher Columbus 27 by Jame A. Coomb Map of the Columbian Encounter and its Aftermath, and their Projections 37 by Norman }. W. Thrower BOOK REVIEWS Map Collections in Australia: A Directory 45 David A. Cobb The History of Cartography. Vol. 2, Bk. 1. Cartography in the Traditional and South Asian Societies 46 Donald C. Johll on Maps born the Mind: Readings in Psychogeography 49 Fred Plaut DEPARTME TS Carte blanche 1 51 by David Woodward Carto acts 61 Awards 49 Exhibits 53 Collections 59 Biographies of Author 55 Final Word 62 by fenny John 011 ETCETERA Index to Advertisers 4 Information for Contributors 63 Corrections 64 ~ MERlDI 9 ADVERTIS G Meridian accepts advertising of product or ervice as it improves communicati n between vendor and buyer. Meridiall will adhere to all La ·tudes & ethical and commonly accepted advertising practices and reserves the right to r ject any advertisement Longitudes to the deemed not relevant r con i tent with the goal f the Map and Geography Round Tabl . Enquiri nth Degree should be addr d t Da id A. Cobb, Ad erti ing Manager, Harvard ap Unk, the worlds most comprehensive mop Map Collection, Harvard College distributor, invites you to explore the planet. Library, Cambridge, MA 02138, Phone (617) 495-2417, Fax (617) 496 Map Unk stocks maps from every corner of the 9802, e-mail ~~ warld and represents every mapmoker lorge and small. -

MEMORY of the WORLD REGISTER Universalis Cosmographia Secundum Ptholomaei Traditionem Et Americi Vespucii Aliorumque Lustrationes REF N° 2004-41

MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii aliorumque Lustrationes REF N° 2004-41 Part A Essential Information 1. Summary The Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii aliorumque Lustrationes by Martin Waldseemüller. N.p. 1507 [St. Dié or Strasbourg, France]. The 1507 printed world map, prepared by the Gymnasium Vosagense, St. Dié, France under the direction of Martin Waldseemüller, is the first map on which the name America appears. The Library of Congress possesses the only known surviving copy of this map. Prepared by the research team in St. Dié, France and reflecting fresh information derived from the Spanish and Portuguese expeditions of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the 1507 World map by Martin Waldseemüller is universally recognized as the first map, printed or manuscript, to reflect a true depiction of a separate Western Hemisphere and the existence of the Pacific Ocean. This monumental cartographic achievement of the early 16th century bears the additional importance as the first printed world wall map and is the document which reflects Waldseemüller’s decision to name the New World “America” in honor of Amerigo Vespucci. In light of the importance in the field of geographic and the history of cartography, Martin Waldseemüller’s monumental 1507 world map should be included in the Memory of the World Register. 2. Nominators Name (1) Dr. James H. Billington, The Librarian of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA Name (2) German Nomination Committee for the Memory of the World Program, Prof. Dr. Joachim- Deleted: m Felix Leonhard (Chairperson) Relationship to the documentary heritage: United States, Library of Congress, owner Until 2003, the map had been held in Germany. -

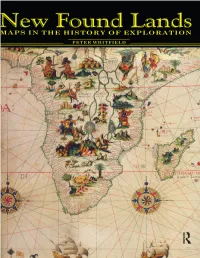

Maps in the History of Exploration Peter Whitfield

NEW FOUND LANDS NJE~V JF(Q)lU[NJD) JLA NJD)§ MAPS IN THE HISTORY OF EXPLORATION PETER WHITFIELD ~ l Routledge ~ ~ Taylor & Fnmds Croup NEW YORK Half-title: The Cape of Good Hope, by Seller, 1675. The most famous maritime landmark in the world, later the base for British expansion into Southern Africa. The British Library Maps C.8.b. 13, f.25. Title page: Waldseemiiller's World Map, 1507. Schloss Wolfegg © Peter Whitfield 1998 Published in the United States of America and Canada in 1998 by Routledge 711 ThirdAvenue, New York, NY 10017, USA First published in 1998 by The British Library Routledge is an imprint ofthe Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitfield, Peter, Dr. New found lands: maps in the history of exploration I Peter Whitfield. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-415-92026-4 (alk. paper) 1. Discoveries in geography. 2. Cartography-History. I. Title. 081.W47 1998 97-47767 910'.9-dc21 CIP Typeset by Bexhill Phototypesetters ISBN 13: 978-0-415-92026-1 (hbk) CONTENTS Preface page vi 1 EXPLORATION IN THE ANCIENT WORLD page 1 2 THE LURE OF THE EAST, 1250-1550 page 22 3 THE NEW WORLD, 1490-1630 page 53 4 THE PACIFIC AND AUSTRALIA, 1520-1800 page 90 5 THE CONTINENTS EXPLORED, 1500-1900 page 127 Postscript EXPLORATION IN THE MODERN WORLD page 185 Bibliographical Note page 197 Index page 198 JP> lR.lE lF A <ClE LEGENDS ARE REQUIRED TO BE beautiful rather than true. The history of exploration is full of legends which, while they are not untrue, contain only a part of the truth.