Encountering Indian Subaltern Experiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Appraising Taxation in Travancore and It's Caste Interference

GIS Business ISSN: 1430-3663 Vol-14-Issue-3-May-June-2019 Re-Appraising Taxation in Travancore and It's Caste Interference REVATHY V S Research Scholar Department Of History University Of Kerala [email protected] 8281589143 Travancore , one of the Princely States in British India and later became the Model State in British India carried a significant role in history when analysing its system of taxation. Tax is one of the chief means for acquiring revenue and wealth. In the modern sense, tax means an amount of money imposed by a government on its citizens to run a state or government. But the system of taxation in the Native States of Travancore had an unequal character or discriminatory character and which was bound up with the caste system. In the case of Travancore and its society, the so called caste system brings artificial boundaries in the society.1 The taxation in Travancore is mainly derived through direct tax, indirect tax, commercial tax and taxes in connection with the specific services. The system of taxation adopted by the Travancore Royal Family was oppressive and which was adversely affected to the lower castes, women and common people. It is proven that the system of taxation used by the Royal Family as a tool for oppression and subjugation and they also used this P a g e | 207 Copyright ⓒ 2019 Authors GIS Business ISSN: 1430-3663 Vol-14-Issue-3-May-June-2019 discriminatorytaxation policies as of the ardent machinery to establish their political domination and establishing their cultural hegemony. Through the analysis and study of taxation in Travancore it is helpful to reconstruct the socio-economic , political and cultural conditions of Travancore. -

Dress As a Tool of Empowerment : the Channar Revolt

Dress as a tool of Empowerment : The Channar Revolt Keerthana Santhosh Assistant Professor (Part time Research Scholar – Reg. No. 19122211082008) Department of History St. Mary’s College, Thoothukudi (Manonmanium Sundaranar sUniversity, Tirunelveli) Abstract Empowerment simply means strengthening of women. Travancore, an erstwhile princely state of modern Kerala was considered as a land of enlightened rulers. In the realm of women, condition of Travancore was not an exception. Women were considered as a weaker section and were brutally tortured.Patriarchy was the rule of the land. Many agitations occurred in Travancore for the upliftment of women. The most important among them was the Channar revolt, which revolves around women’s right to wear dress. The present paper analyses the significance of Channar Revolt in the then Kerala society. Keywords: Channar, Mulakkaram, Kuppayam 53 | P a g e Dress as a tool of Empowerment : The Channar Revolt Kerala is considered as the God’s own country. In the realm of human development, it leads India. Regarding women empowerment also, Kerala is a model. In women education, health indices etc. there are no parallels. But everything was not better in pre-modern Kerala. Women suffered a lot of issues. Even the right to dress properly was neglected to the women folk of Kerala. So what Kerala women had achieved today is a result of their continuous struggles. Women in Travancore, which was an erstwhile princely state of Kerala, irrespective of their caste and community suffered a lot of problems. The most pathetic thing was the issue of dress. Women of lower castes were not given the right to wear dress above their waist. -

Download Download

Volume 02 :: Issue 01 April 2021 A Global Journal ISSN 2639-4928 CASTE on Social Exclusion brandeis.edu/j-caste PERSPECTIVES ON EMANCIPATION EDITORIAL AND INTRODUCTION “I Can’t Breathe”: Perspectives on Emancipation from Caste Laurence Simon ARTICLES A Commentary on Ambedkar’s Posthumously Published Philosophy of Hinduism - Part II Rajesh Sampath Caste, The Origins of Our Discontents: A Historical Reflection on Two Cultures Ibrahim K. Sundiata Fracturing the Historical Continuity on Truth: Jotiba Phule in the Quest for Personhood of Shudras Snehashish Das Documenting a Caste: The Chakkiliyars in Colonial and Missionary Documents in India S. Gunasekaran Manual Scavenging in India: The Banality of an Everyday Crime Shiva Shankar and Kanthi Swaroop Hate Speech against Dalits on Social Media: Would a Penny Sparrow be Prosecuted in India for Online Hate Speech? Devanshu Sajlan Indian Media and Caste: of Politics, Portrayals and Beyond Pranjali Kureel ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste Discourse? Anurag Bhaskar, Bluestone Rising Scholar 2021 Award Caste-ing Space: Mapping the Dynamics of Untouchability in Rural Bihar, India Indulata Prasad, Bluestone Rising Scholar 2021 Award Caste, Reading-habits and the Incomplete Project of Indian Democracy Subro Saha, Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2021 Clearing of the Ground – Ambedkar’s Method of Reading Ankit Kawade, Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2021 Caste and Counselling Psychology in India: Dalit Perspectives in Theory and Practice Meena Sawariya, Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2021 FORUM Journey with Rural Identity and Linguicism Deepak Kumar Drawing on paper; 35x36 cm; Savi Sawarkar 35x36 cm; Savi on paper; Drawing CENTER FOR GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT + SUSTAINABILITY THE HELLER SCHOOL AT BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY CASTE A GLOBAL JOURNAL ON SOCIAL EXCLUSION PERSPECTIVES ON EMANCIPATION VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 JOINT EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Laurence R. -

Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 1 Jan-2019 Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Subrahmanian, Maya (2019). Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(2), 1-10. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss2/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Autonomous Women’s Movement in Kerala: Historiography By Maya Subrahmanian1 Abstract This paper traces the historical evolution of the women’s movement in the southernmost Indian state of Kerala and explores the related social contexts. It also compares the women’s movement in Kerala with its North Indian and international counterparts. An attempt is made to understand how feminist activities on the local level differ from the larger scenario with regard to their nature, causes, and success. Mainstream history writing has long neglected women’s history, just as women have been denied authority in the process of knowledge production. The Kerala Model and the politically triggered society of the state, with its strong Marxist party, alienated women and overlooked women’s work, according to feminist critique. -

Women and Political Change in Kerala Since Independence

WOMEN AND POLITICAL CHANGE IN KERALA SINCE INDEPENDENCE THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE COCHIN UNIVERSITY or SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY FOR THE AWARD or THE DEGREE or DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNDER THE FACULTY or SOCIAL SCIENCES BY KOCHUTHRESSIA, M. M. UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. J. T. PAYYAPPILLY PROFESSOR SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES COCHIN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COCHIN - 682 022, KERALA October 1 994 CERTIFICATE Certified that the thesis "Women and Political Change in Kerala since Independence" is the record of bona fide research carried out by Kochuthressia, M.M. under my supervision. The thesis is worth submitting for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Faculty of Social Sciences. 2’/1, 1 :3£7:L§¢»Q i9¢Z{:;,L<‘ Professorfir.J.T.§ay§a%pilly///// ” School of Management Studies Cochin University of Science and Technology Cochin 682 022 Cochin 682 022 12-10-1994 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is the record of bona fide research work carried out knrxme under the supervision of Dr.J.T.Payyappilly, School (HS Management. Studies, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Cochin 682 022. I further declare that this thesis has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship or other similar title of recognition. ¥E;neL£C-fl:H12§LJJ;/f1;H. Kochuthfe§§ia7—§iM. Cochin 682 022 12-10-1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Once the topic "Women and Political Change in Kerala since Independence" was selected for the study, I received a lot of encouragement from many men and women who'are genuinely concerned about the results (M5 gender discrimination. -

"An Evaluation of the History of Pentecostal Dalits in Kerala"

INTRODUCTION Research and studies have recently been initiated on the under-privileged people, namely, the Dalits in India. Though it is an encouraging fact, yet more systematic and classified studies are required because the Dalits are located over a wide range of areas, languages, cultures, and religions, where as the problems and solutions vary. Since the scholars and historians have ignored the Dalits for many centuries, a general study will not expose sufficiently their actual condition. Even though the Dalit Christian problems are resembling, Catholics and Protestants are divided over the issues. Some of the Roman Catholic priests are interested and assert their solidarity with the Dalit Christian struggle for equal privilege from the Government like other Hindu Dalits. On the other hand, most Protestant denominations are indifferent towards any public or democratic means of agitation on behalf of Dalit community. They are very crafty and admonish Dalit believers only to pray and wait for God’s intervention. However, there is an apparent intolerance in the Church towards the study and observations concerning the problems of Dalit Christians because many unfair treatments have been critically exposed. T.N. Gopakumar, the Asia Net programmer, did broadcast a slot on Dr. P.J. Joseph, a Catholic priest for thirty -eight years in the Esaw Church, on 22 October 2000. 1 Joseph advocated for the converted Christians that the Church should upgrade their place and participation in the leadership of the Church. The very next day, 1 T.N.Gopakumar, Kannady [Mirror-Mal], Asia Net , broadcast on 22 October, 2000. 1 with the knowledge of the authorities, a group of anti-Dalit Church members, attacked him and threw out this belongings from his room in the headquarters at Malapparambu, Kozhikode, where he lived for about thirty years. -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

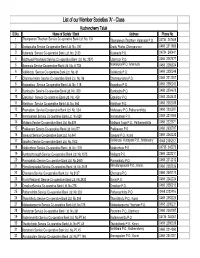

List of Our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No

List of our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No. Name of Society / Bank Address Phone No. 1 Thumpamon Thazham Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 134 Thumpamon Thazham, Kulanada P.O. 04734 267609 2 Arattupuzha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 787 Arattu Puzha, Chengannoor 0468 2317865 3 Kulanada Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2133 Kulanada P.O. 04734 260441 4 Mezhuveli Panchayat Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2570 Ullannoor P.O. 0468 2287477 5 Aranmula Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. A 703 Nalkalickal P.O. Aranmula 0468 2286324 6 Vallikkodu Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 61 Vallikkodu P.O. 0468 2350249 7 Chenneerkkara Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 96 Chenneerkkara P.O. 0468 2212307 8 Kaippattoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 115 Kaipattoor P.O. 0468 2350242 9 Kumbazha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 330 Kumbazha P.O. 0468 2334678 10 Elakolloor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 459 Elakolloor P.O. 0468 2342438 11 Elanthoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 460 Elanthoor P.O. 0468 2362039 12 Pramadom Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 534 Mallassery P.O.,Pathanamthitta 0468 2335597 13 Naranganam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.628 Naranganam P.O. 0468 2216506 14 Mylapra Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.639 Mailapra Town P.O., Pathanamthitta 0468 2222671 15 Prakkanam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.677 Prakkanam P.O. 0468 2630787 16 Vakayar Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.847 Vakayar P.O., Konni 0468 2342232 17 Janatha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.1042 Vallikkodu -Kottayam P.O., Mallassery 0468 2305212 18 Mekkozhoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

Adapting to Climate Change in Urban Areas

Human Settlements Discussion Paper Series Theme: Climate Change and Cities - 1 Adapting to Climate Change in Urban Areas The possibilities and constraints in low- and middle-income nations David Satterthwaite, Saleemul Huq, Mark Pelling, Hannah Reid and Patricia Romero Lankao This is a working paper produced by the Human Settlements Group and the Climate Change Group at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). The authors are grateful to the Rockefeller Foundation both for supporting the preparation of this paper and for permission to publish it. It is based on a background paper prepared for the Rockefeller Foundation’s Global Urban Summit, Innovations for an Urban World, in Bellagio in July 2007. For more details of the Rockefeller Foundation’s work in this area, see http://www.rockfound.org/initiatives/climate/climate_change.shtml The financial support that IIED’s Human Settlements Group receives from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and the Royal Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DANIDA) supported the publication and dissemination of this working paper. ii ABOUT THE AUTHORS Dr David Satterthwaite is a Senior Fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) and editor of the international journal, Environment and Urbanization. He has written or edited various books on urban issues, including Squatter Citizen (with Jorge E. Hardoy), The Earthscan Reader on Sustainable Cities, Environmental Problems in an Urbanizing World (with Jorge E. Hardoy and Diana Mitlin) and Empowering Squatter Citizen, Local Government, Civil Society and Urban Poverty Reduction (with Diana Mitlin), published by Earthscan, London. He is an Honorary Professor at the University of Hull and in 2004 was one of the recipients of the Volvo Environment Prize. -

Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly

TAMIL NADU LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY (Thirteenth Assembly) ADDRESS LIST OF MEMBERS (First Edition) 2006 (As on 1.4.2007) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT, CHENNAI-600 009. 2 3 Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly GOVERNOR His Excellency Thiru SURJIT SINGH BARNALA Raj Bhavan, Chennai-600 022. Telephone : Office : 2567 0099 Intercom : 5618 Residence : 2235 1313 CHIEF MINISTER Hon. Dr. M. KARUNANIDHI New No.15, Old No. 8, 4th Street, Gopalapuram, Chennai-600 086. Telephone: Office : 2567 2345 Intercom : 5666 Residence : 2811 5225 SPEAKER HON. THIRU R. AVUDAIAPPAN Office : Secretariat, Chennai-600 009. Telephone : Office : 2567 2708, 2567 0271/101 Intercom : 5610 Residence : 2493 9794 “Ezhil” P.S. Kumarasamy Raja Salai, Raja Annamalaipuram, Chennai-600 028. 4 DEPUTY SPEAKER HON. THIRU V.P. DURAISAMY Office : Secretariat, Chennai-600 009. Telephone : Office : 2567 2656, 2567 0271/102 Intercom : 5640 Residence : 2464 3366 No.9, Judges New Quarters, P.S. Kumarasamy Raja Salai, Raja Annamalaipuram, Chennai-600 028. LEADER OF THE HOUSE HON. PROF. K. ANBAZHAGAN Office : Secretariat, Chennai-600 009. Telephone : Office : 2567 2265 Intercom : 5612 Residence : 2644 6274 No.58, Aspiran Garden, 2nd Street, Kilpauk, Chennai-600 010. LEADER OF OPPOSITION SELVI J JAYALALITHAA Office : Secretariat, Chennai-600 009. Telephone : Office : 2567 0821, 2567 0271/104 Intercom : 5644 Residence : 2499 2121, 2499 1414 “Veda Nilayam” 81/36, Poes Garden, Chennai-600 086. 5 CHIEF GOVERNMENT WHIP Thiru R. SAKKARAPANI Office : Secretariat, Chennai-600 009. Telephone : Office : 2567 1495, 2567 0271/103 Intercom : 5605 Residence : 2464 2981 “Senthamarai”, No. 5, P.S. Kumarasamy Raja Salai, Raja Annamalaipuram, Chennai-600 028. SECRETARY Thiru M. SELVARAJ, B.Sc., B.L., Office : Secretariat, Chennai-600 009. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Pathanamthitta District from 28.03.2021To03.04.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Pathanamthitta district from 28.03.2021to03.04.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 PUTHENPURAKK PATHANA Shaiju si of AL HOUSE 03-04-2021 449/2021 U/s 59, MTHITTA police BAILED BY 1 JAMES P G GEORGE P T CHENGARA PO Vettoor at 20:45 279 IPC & 185 Male (Pathanamth Pathanamthitt POLICE PATHANAMTHITT Hrs MV ACT itta) a A 444/2021 U/s PATHANA Akhil bhavanam 03-04-2021 Ramesh 23, Central 279 IPC MTHITTA BAILED BY 2 Akhil Saji puthussery bhagam at 09:30 kumar, SI of Male junction PTA 3(1)r/w 181 (Pathanamth POLICE village vayalar pta Hrs Police MV act itta) palanilkunnathil PATHANA house eramuriyil 02-04-2021 443/2021 U/s Philip 29, central MTHITTA sanju joseph BAILED BY 3 jonin skariya ,chengara at 15:40 118(a) of KP mathue Male jungtion (Pathanamth SI of Police POLICE malayalapuzha po Hrs Act itta) pta ph: 9072903892 Lekshmi nivas PATHANA MUNDUKOTTACK 02-04-2021 SASIKUMA 32, 442/2021 U/s MTHITTA Rejimon, SI of BAILED BY 4 PRASANTH AL PO Aban junction at 15:39 R Male 279 IPC (Pathanamth Police POLICE PATHANAMTHITT Hrs itta) A 9447555794 PATHANA Kalleckal kavumkal 01-04-2021 441/2021 U/s Narayanan 51, College MTHITTA Sunny k SI of BAILED BY 5 Ajayakumar Imali Omaloor po at 22:20 279 IPC & 185 nair Male junction pta (Pathanamth Police POLICE Pathanamthitta Hrs MV ACT itta)