ITB Journal-December-2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Configuration Parameters

Good news, everyone! User Documentation Version: 2020-01-01 M. Brutman ([email protected]) http://www.brutman.com/mTCP/ Table of Contents Introduction and Setup Introduction..............................................................................................................................................................8 What is mTCP?...................................................................................................................................................8 Features...............................................................................................................................................................8 Tested machines/environments...........................................................................................................................9 Licensing...........................................................................................................................................................10 Packaging..........................................................................................................................................................10 Binaries.....................................................................................................................................................................10 Documentation..........................................................................................................................................................11 Support and contact information.......................................................................................................................11 -

Imperial College of Science and Technology, University of London, Department of Computing

Imperial College of Science and Technology, University of London, Department of Computing. HIGH EFFICIENCY, CHARACTER-ORIENTED, LOCAL AREA NETWORKS by Martin Cripps This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and the Diploma of Imperial College of Science and Technology, January 1988. For Clare Attempt the end His reasons are as two grains of wheat but never stand to doubt hid in two bushels of chaff. nothing's so hard You shall seek all day ere you find them but search and when you have found them will find it out they are not worth the search. Robert Herrick (1591-1674) William Shakespeare (1564-1616) 1 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the problem of interconnecting character-oriented devices over local area networks by investigating significant aspects of hardware, software, protocol and operational factors. It proposes effective and efficient solutions which were tested during a full-scale experiment The results of that experiment demonstrate convenient, cost-effective and reliable operation. The novelty of this investigation arises from its character-oriented approach. Much work has been carried out by others on local area networks which transfer blocks of data efficiently, however, a large majority of installed devices operate on a character-by-character basis and will continue so to do for some considerable time. This study is approached through analysis of the low efficiency of international standard networks for this class of device which defines the scope of this work. An original analysis of the potential mechanisms which can be used to give high efficiency and low delay for this class of transfer is then derived. -

The Last Great Commodore 64 Commercial Software Sale

theMONITOR CommodoreUsersGroupofSaskatchewan 361729thAvenue Regina,SK S4S2P8 Tel:(306)584-1736 BBS:(306)586-6608 President eachother.Membershipdues($15)arepro-rated, TristanMiller 584-1736 basedonaJanuarytoDecemberyear.Anaddi- VicePresident tional$5willbechargedformemberswishing ByronPurse 586-1601 theirnewsletterstobemailedtothem. Secretary/Treasurer KenDanylzczuk 545-0644 Anyone interested in computing is welcome to Editor attendanymeeting.Membersareencouragedto TristanMiller 584-1736 submitpublicdomainandsharewaresoftware AssistantEditors forinclusionintheCUGSDiskLibrary.These ByronPurse 586-1601 programsaremadeavailabletomembersat$3.00 R LyndonSoerensen 565-2167 each(discountedpriceswhenbuyingbulk).Since KeithKasha 522-5317 someprogramsonthedisksarefrommagazines, 64Librarian individualmembersareresponsiblefordeleting StanMustatia 789-8167 anyprogramthattheyarenotentitledtobylaw 128Librarian (youmustbetheownerofthemagazineinwhich O KeithKasha 522-5317 theoriginalprogramwasprinted).Tothebestof MemberatLarge ourknowledge,allsuchprogramsareidentifiedin HerbThompson 543-3460 theirlistings. T TheMonitorispublishedmonthlybytheCom- Otherbenefitsofclubmembershipincludeaccess modore User's Group of Saskatchewan toourdiskcopyingservice,tomakebackupsof I (CUGS).MeetingsareheldonthefirstWednes- copy-protectedsoftware,anymemberswhoowna dayofeverymonthinMillerHighSchool'scafete- modemandwishtocallourbulletinboardwill ria annex, unless otherwise noted. The next receiveincreasedaccesstothemessageandfile meetingwillbeheldonDecember1,1993from areas.Theboardoperatesat300to2400baud,24 -

X/84 Documentation Release 2.0.15

x/84 Documentation Release 2.0.15 Jeff Quast Jun 17, 2020 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Quickstart................................................3 1.2 Documentation, Support, Issue Tracking................................4 2 Project Details 5 2.1 Compatible Clients............................................5 2.2 Binding to port 23............................................6 2.2.1 Linux..............................................6 2.2.2 Solaris 10............................................6 2.2.3 BSD...............................................6 2.2.4 Other..............................................6 2.3 Other Telnet BBS Systems........................................7 2.3.1 How x/84 compares.......................................7 2.4 History..................................................8 2.5 What does x/84 mean?..........................................8 2.6 Future Directions.............................................8 3 Running a message server 11 3.1 Configuring a hub............................................ 11 3.2 Configuring a leaf node......................................... 12 3.3 Authorship................................................ 12 4 Doors 13 4.1 Dosemu.................................................. 14 5 Web server 15 5.1 Starting a web server........................................... 15 5.2 Lookup path............................................... 16 5.3 Serving static files............................................ 16 5.4 Writing a web module.......................................... 16 5.4.1 -

OSI Model -3.2

مفهوم و کاربرد شبکه های کامپیوتر تألیف و گرد آوری:میثاق نوازنی ویرایش اول مفهوم و کاربرد شبکه های کامپیوتر www.misaghnavazeni.com هوالعالم سرشناسه : نوازنی، میثاق عنوان و نام پدیدآور: مفهوم و کاربرد شبکههای کامپیوتر / تالیف و گردآوری میثاق نوازنی مشخصات ظاهری: 163 ص شابک :978-600-04-2507-4 وضعیت فهرست نویسی: فیپا موضوع: شبکههای کامپیوتری موضوع: شبکههای کامپیوتری – معماری رده بندی کنگره: 73191م9ن/TK5305/5 رده بندی دیویی:004/6 شماره کتابشناسی ملی: 1714280 2 مفهوم و کاربرد شبکه های کامپیوتر www.misaghnavazeni.com فهرست مطالب: مقدمه:....................................................................................................7 8....................................................................................... : Network history 33................................................................................ : Networking Basics-3.0 32......................................................................... : Network communication-3.3 16....................................................................................... :OSI model -3.2 55............................................................................................ :TCP/IP-3.1 65................................................................................... :Network cables-2.3 76..................................................................... :Network Interface Adapters-2.2 80.................................................................................... :Network Hubs-2.1 84.......................................................................... -

The Puzzle Fun Book

The Puzzle Fun Book Plus (Almost) Everything You (Kind of) Wanted to Know about IT …but Not Enough to Ask Contents of the Puzzle Fun Book General Information 11 What is RAM? 13 What is a peripheral? 13 What is a storage device? 15 What is an I/O Device? 17 What is a broadband network? 19 What is “The Cloud” and why (apparently) should I care? 21 So what about fezzes and bowties? 3 The Internet 25 What is a URL? 27 What is a domain? 29 What does a “web browser” do? 31 What is an IP address? 33 What does the term HTML mean? 35 What is a Portal? 37 What is a blog? 39 What is Remote Access? Security 71 What makes my computer shut down for no good 43 How can I secure my laptop? reason? 45 How can data on my computer be protected from sneaky 73 Why is my computer making a grinding noise? people? 75 What causes the internet to be slow? 47 Is it remotely possible to locate my laptop (and other 77 Why does my computer insist I eject a USB (flash) devices) remotely? drive before removing it? 49 What’s the deal with Viruses and Trojans? 79 What does it mean if my web browser stops and I get 51 Can a firewall protect me from a computer virus? a ‘Flash has stopped working’ message? 53 Is it safe to use a free Wi-Fi network? Advice 55 Is it okay to do online banking using a public wireless 83 What questions should business owners ask before Internet connection? 5 investing in a technology solution? 57 Do I really need to care about my privacy online? 85 What should I consider before using a Cloud service 59 What’s the difference between spam e-mail and phishing? to store my documents and important data? 61 What happens when a site I use gets ‘hacked’? Did you know? Technical Issues 89 Oh Really? 91 Yes, Really. -

The Market Is Growing AWS End User Compute Offerings Vs

SYNCHRONET WINDOWS VIRTUAL DESKTOP VS. AWS EUC OFFERINGS The Market is Growing AWS End User Compute Offerings vs. Windows Virtual Desktop With the massive shift to a work and learn from home world, many organizations and schools need to find ways to enable their employees and students to access the applications they need from anywhere, on any device. The market of providers who offer services and tools to deliver this capability is growing. This whitepaper will dive into, and compare, the technical and business features of AWS End User Compute services such as WorkSpaces and AppStream 2.0 with Microsoft’s Windows Virtual Desktop offering. 1 SYNCHRONET WINDOWS VIRTUAL DESKTOP VS. AWS EUC OFFERINGS Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ………………………………………………………….......................................................................... Page 3 ARCHITECTURE ..………………………………………………………………………………………………………...............................…..…. Page 4 Architecture Background ..............................………………………….………………………………………………………... Page 4 Services’ Architecture ..............................………………………….………………………………………………………......... Page 6 CAPABILITIES ......................…………………………………………………………………………………….……………………………………. Page 12 PRICING ....................................………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………… Page 13 Pricing Background ..............................……………………………………………………………………..…………………….. Page 13 Services’ Pricing ...............................…………………………………..……….…………………………..………………………. Page 13 Example Pricing Scenarios .........................................…………………………….....................…………………. -

Pioneers of Online Learning in Alberta PIONEERS of ONLINE LEARNING in ALBERTA

Pioneers of Online Learning in Alberta PIONEERS OF ONLINE LEARNING IN ALBERTA A micro memoir of my days on the bleeding edge of online learning . convergence of Internet and distance education. SciTech BBS . Download this book PDF with hyperlinks PDF for print EPUB EPUB 3 Pioneers of Online Learning in Alberta by Steve Swettenham is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Unless otherwise noted, this book is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License also known as a CC-BY-NC-SA license. This means you are free to copy, redistribute, modify or adapt this book non-commercially, as long as you license your creation under the identical terms and credit the authors with the following attribution: Pioneers of Online Learning in Alberta, by Steve Swettenham used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 international license. Additionally, if you redistribute this textbook, in whole or in part, in either a print or digital format, then you must retain on every physical and/or electronic page the following attribution: Download this book for free at https://imem.pressbooks.com or https://mem-mem.com/on-linelearning If you use this textbook as a bibliographic reference, then you can cite the book as follows: Swettenham, Steve. Pioneers of Online Learning in Alberta. On-LineLearning.ca, 2019. https://mem- mem.com/on-linelearning/. Contents Acknowledgements vii Revisions ix LITTLE KNOWN FACTS Internet Educational BBS Pioneers -

Post-Modemism: the Role of User Adoption of Teletext, Videotex & Bulletin Board Systems in the History of the Internet

POST-MODEMISM: THE ROLE OF USER ADOPTION OF TELETEXT, VIDEOTEX & BULLETIN BOARD SYSTEMS IN THE HISTORY OF THE INTERNET by Jay Kelly McKinnon B.A. University of British Columbia, 2003 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology Ó Jay Kelly McKinnon 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Jay Kelly McKinnon Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Post-modemism: the role of user adoption of teletext, videotex & bulletin board systems in the history of the Internet Examining Committee: Chair: Roman Onufrijchuk, Senior Lecturer Richard Smith Senior Supervisor Professor Peter Anderson Supervisor Associate Professor Adam Holbrook External Examiner Associate Director, Center for Policy Research on Science and Technology, Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: March 29, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract The enduring policy conflicts of the Information Age increasingly demand a history of technology that acknowledges the legacy of accumulated user experience across successive paradigms and generations of communication media. Interrogation of the histories of Internet, teletext, videotex and bulletin board system (BBS) technologies, reveal the 1980s as a watershed decade for the radically decentralized socialization of digital communication. While each new technical paradigm requires cultural practices to socialize the products of engineering, the prevalence of elite- and infrastructure-focused histories reflect a systematic preference for describing centralized processes of engineering. -

Etc/Services

# /etc/services: # $Id: services,v 1.48 2009/11/11 14:32:31 ovasik Exp $ # # Network services, Internet style # IANA services version: last updated 2009-11-10 # # Note that it is presently the policy of IANA to assign a single well-known # port number for both TCP and UDP; hence, most entries here have two entries # even if the protocol doesn't support UDP operations. # Updated from RFC 1700, ``Assigned Numbers'' (October 1994). Not all ports # are included, only the more common ones. # # The latest IANA port assignments can be gotten from # http://www.iana.org/assignments/port-numbers # The Well Known Ports are those from 0 through 1023. # The Registered Ports are those from 1024 through 49151 # The Dynamic and/or Private Ports are those from 49152 through 65535 # # Each line describes one service, and is of the form: # # service-name port/protocol [aliases ...] [# comment] tcpmux 1/tcp # TCP port service multiplexer tcpmux 1/udp # TCP port service multiplexer rje 5/tcp # Remote Job Entry rje 5/udp # Remote Job Entry echo 7/tcp echo 7/udp discard 9/tcp sink null discard 9/udp sink null systat 11/tcp users systat 11/udp users daytime 13/tcp daytime 13/udp qotd 17/tcp quote qotd 17/udp quote msp 18/tcp # message send protocol msp 18/udp # message send protocol chargen 19/tcp ttytst source chargen 19/udp ttytst source ftp-data 20/tcp ftp-data 20/udp # 21 is registered to ftp, but also used by fsp ftp 21/tcp ftp 21/udp fsp fspd ssh 22/tcp # The Secure Shell (SSH) Protocol ssh 22/udp # The Secure Shell (SSH) Protocol telnet 23/tcp telnet 23/udp -

FIRE ESCAPE's St. Louis BBS Directory: DECEMBER 1993

FIRE ESCAPE'S St. Louis BBS Directory: DECEMBER 1993 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ All PREVIOUS "Directories" are now outdated, please delete them! The Legends and Directory Information are at the End. ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ BULLETIN BOARD SYSTEM NAME L# P PHONE # STATS SYSOP NAME HOURS MODEM SOFT ============================ == = ======== === ============== ===== ===== ==== 19th Hole BBS, The -- - 487-5782 --- Mr. Bill 24 DSH-B WWIV 4 Star BBS -- - 225-8821 C Mike 24 2.4-N PCBD Absolute Value 02 - 731-7935 --- Art Hebbeler 24 2.4-N MISC Absolute Value -- - 731-7934 P Art Hebbeler 24 32b-N MISC Absolute Value -- - 895-2616 --- Art Hebbeler 24 2.4-N MISC Access Denied: MAC BBS -- - 846-5565 --- Skip 24 32b-B HERM Access Imaging -- - 664-8220 --- ? 24 32b-B MISC Ace's Place -- S 272-5436 N Ace 24 32b-B SYNC ACME Acres BBS -- - 351-5227 --- Buster Bunny 24 32b-B WWIV Adults Unlimited -- - 481-7101 C Dirty Old Man 24 32b-B TLGD Affinity ADULT Multiline BBS 19 - 771-6800 --- Aqualung 24 32b-B MISC After Midnight Sushi Bar -- - 772-3428 A The Jap 00-12 2.4-N WWIV After Thought -- - 423-6312 --- Shade Tree 24 2.4-N WWIV Alien's -- - 349-5179 --- Alien 24 2.4-N C-64 Amazon, The -- - 846-8758 --- Audiophile 24 DSH-B WWIV American Liberator, The -- - 343-4759 --- ? 24 32b-B WWIV Amiga Only -- - 428-4737 --- Mike Kraml 24 DSH-B OPUS Andromeda II -- - 869-5171 --- ? 24 2.4-N UNKW Arcadia BBS -- - 429-4448 --- Terror 24 2.4-N MISC Arena, The L1 - 845-6849 --- Jake Blues 24 32b-B VBBS Arena, The L2 - 845-6859 --- Jake Blues 24 32b-B VBBS Asgardian Realm, The -- - 291-6762 --- Lancer 24 DSH-B WWIV Asylum II, The -- - 846-8412 N The Billiken 24 32b-B VBBS Atlantis BBS -- - 426-7873 --- Plutarch 24 32b-B WWIV Aviary, The -- - 544-2569 * FlyBoy 24 2.4-N WWIV Babble-On: Land of Kazhbu -- - 481-6298 --- Kadet Kazhbu 24 9.6-B SLGT Barb's Lookout Window -- - 894-0919 * Barb C. -

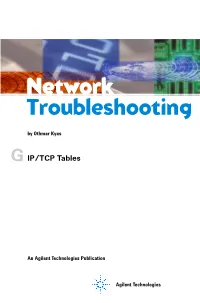

IP/TCP Tables

Network Troubleshooting by Othmar Kyas G IP/TCP Tables An Agilent Technologies Publication Agilent Technologies IP/TCP Tables G G.1 IP Protocol Assignments Code Protocol Description Code Protocol Description 0 Reserved 55-60 Unassigned 1 ICMP Internet Control Message 61 any host internal protocol 2 IGMP Internet Group Management 62 CFTP CFTP 3 GGP Gateway-to-Gateway 63 any local network 4 IP IP in IP (encapsulation) 64 SAT-EXPAK SATNET and Backroom EXPAK 5 ST Stream 65 KRYPTOLAN Kryptolan 6 TCP Transmission Control 66 RVD MIT Remote Virtual Disk Protocol 7 UCL UCL 67 IPPC Internet Pluribus Packet Core 8 EGP Exterior Gateway Protocol 68 any distributed file system 9 IGP any Private Interior Gateway 69 SAT-MON SATNET Monitoring 10 BBN-RCC-MON BBN RCC Monitoring 70 VISA VISA Protocol 11 NVP-II Network Voice Protocol 71 IPCV Internet Packet Core Utility 12 PUP PUP 72 CPNX Computer Protocol Network 13 ARGUS ARGUS Executive 14 EMCON EMCON 73 CPHB Computer Protocol Heart Beat 15 XNET Cross Net Debugger 74 WSN Wang Span Network 16 CHAOS Chaos 75 PVP Packet Video Protocol 17 UDP User Datagram 76 BR-SAT-MON Backroom SATNET Monitoring 18 MUX Multiplexing 77 SUN-ND SUN ND PROTOCOL-Temporary 19 DCN-MEAS DCN Measurement Subsystems 78 WB-MON WIDEBAND Monitoring 20 HMP Host Monitoring 79 WB-EXPAK WIDEBAND EXPAK 21 PRM Packet Radio Measurement 80 ISO-IP ISO Internet Protocol 22 XNS-IDP XEROX NS IDP 81 VMTP VMTP 23 TRUNK-1 Trunk-1 82 SECURE-VMTP SECURE-VMTP 24 TRUNK-2 Trunk-2 83 VINES VINES 25 LEAF-1 Leaf-1 84 TTP TTP 26 LEAF-2 Leaf-2 85 NSFNET-IGP NSFNET-IGP