The Lithographic Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Artist and the American Land

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1975 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A., "A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land" (1975). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 112. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME I is the book on which this exhibition is based: A Sense at Place The Artist and The American Land By Alan Gussow Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-154250 COVER: GUSSOW (DETAIL) "LOOSESTRIFE AND WINEBERRIES", 1965 Courtesy Washburn Galleries, Inc. New York a s~ns~ 0 ac~ THE ARTIST AND THE AMERICAN LAND VOLUME II [1 Lenders - Joslyn Art Museum ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM, OBERLIN COLLEGE, Oberlin, Ohio MUNSON-WILLIAMS-PROCTOR INSTITUTE, Utica, New York AMERICAN REPUBLIC INSURANCE COMPANY, Des Moines, Iowa MUSEUM OF ART, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, University Park AMON CARTER MUSEUM, Fort Worth MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON MR. TOM BARTEK, Omaha NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington, D.C. MR. THOMAS HART BENTON, Kansas City, Missouri NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, Lincoln MR. AND MRS. EDMUND c. -

America Past

A Teacher’s Guide to America Past Sixteen 15-minute programs on the social history of the United States for high school students Guide writer: Jim Fleet Series consultant: John Patrick 01987 KRMA-W, Denver, Colorado and Agency for Instructional Technology Bloomington, Indiana AH rights reserved. This guide, or any part of it, may not be reproduced without written permission. Review questions in this guide maybe reproduced and distributed free to students. All inquiries should be addressed to: Agency for Instructional Technology Box A Bloomington, Indiana 47402 Table Of Contents Introduction To The AmericaPastSeries . 4 About Jim Fleet . ...!.... 5 America Past: An Overview . 5 How To Use This Guide . 5 Sources On People And Places In America Past . 5 Programs I. New Spain . 6 2. New France . 9 3. The Southern Colonies . 11 4. New England Colonies . 13 5. Canals and Steamboats . 16 6. Roads and Railroads, . .19 7. The Artist’s View . ... ..,.. 22 8. The Writer’s View . ...25 9. The Abolitionists . ...27 10. The Role of Women . ...29 ll. Utopias . ...31 12. Religion . ...33 13. Social Life . ...35 14. Moving West . ...38 15. The Industrial North . ...41 16. The Antebellum South . ...43 Textbook Correlation Chart . ...46 AnswerKey . ...48 Introduction To The America Past Series Over the past thirty years, it has been my experience that most textbooks and visual aids do an adequate job of cover- ing the political and economic aspects of American history UntiI recently however, scant attention has been given to social history. America Past was created to fill that gap. Some programs, such as those on religion and utopias, elaborate upon topics that may receive only a paragraph or two in many texts. -

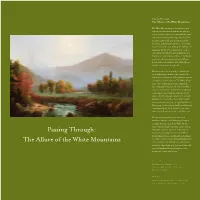

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W. -

N E W S L E T T E R

N E W S L E T T E R Volume 55, Nos. 3 & 4 Fall 2018 Saco River, North Conway, Benjamin Champney (1817–1907), oil on canvas, 1874. Champney described the scenery along the Saco River, with its “thousand turns and luxuriant trees,” as “a combination of the wild and cultivated, the bold and graceful.” New Hampshire Historical Society. Documenting the Life and Work of Benjamin Champney The recent purchase of a collection of family papers some of the artist’s descendants live today. Based on adds new depth to the Society’s already strong evidence within the collection, these papers appear to resources documenting the life and career of influential have been acquired around 1960 by University of New White Mountain artist Benjamin Champney. A native Hampshire English professor William G. Hennessey of New Ipswich, Champney lived with his wife, from the estate or heirs of Benjamin Champney’s Mary Caroline (“Carrie”), in Woburn, Massachusetts, daughter, Alice C. Wyer of Woburn, the recipient of near his Boston studio, but spent summers in North many of the letters. Conway, producing and selling paintings to tourists. The collection also includes handwritten poems by The new collection includes 120 letters, some from Benjamin Champney, photographs of his Guatemalan the artist and others from his father (also named relatives, a photograph of Carrie Champney, and a Benjamin); from his brother Henry Trowbridge diary she kept during the couple’s 1865 trip to Europe. Champney; and from his son, Kensett Champney, the latter writing from his home in Guatemala, where (continued on page 4) New Hampshire Historical Society Newsletter Page 2 Fall 2018 President’s Message Earlier this year the New Hampshire Center for Public Policy Studies closed its doors. -

Landscapes in Maine 1820-1970: a Sesquicentennial Exhibition

LANDSCAPE IN MAINE 1820-1970 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/landscapesinmainOObowd LANDSCAPE IN MAINE 1820-1970 Landscape in Maine 1820-1970 Jl iSesquicentennial exhibition Sponsored by the Maine Federation of Women's Clubs, through a grant from Sears-Roebuck Foundation, The Maine State Commission on the Arts and Humanities, Colby College, Bowdoin College and the University of Maine at Orono. Colby College Art Museum April 4 — May 10 Bowdoin College Museum of Art May 21 — June 28 Carnegie Gallery, University of Maine, Orono July 8 — August 30 The opening at Colby College to be on the occasion of the first Arts Festival of the Maine Federation of Women's Clubs. 1970 is the Sesquicentennial year of the State of Maine. In observance of this, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, the Carnegie Gallery of the University of Maine at Orono and the Colby College Art Museum are presenting the exhibition. Landscape in Maine, 1820-1970. It was during the first few years of Maine's statehood that American artists turned for the first time to landscape painting. Prior to that time, the primary form of painting in this country had been portraiture. When landscape appeared at all in a painting it was as the background of a portrait, or very occasionally, as the subject of an overmantel painting. Almost simultaneously with the artists' interest in landscape as a suitable sub- ject for a painting, they discovered Maine and its varied landscape. Since then, many of the finest American artists have lived in Maine where they have produced some of their most expressive works. -

Telling New England's Stories

BY PETER TRIPPI TRACK INSIDE TELLING NEW ENGLAND’S STORIES n view near Boston from later this year through March 2021 is In preparation for this project, Carlisle and I reviewed hundreds of paint- a unique new exhibition, Artful Stories: Paintings from Historic ings before narrowing the list down to this group of 45 “top hits.” It has been New England. Its distinctive character derives from the remark- a pleasure to work with her while drawing upon our complementary perspec- Oable organization that owns all 45 of its artworks, 14 of which tives to ensure that each painting tells an interesting story. Carlisle’s expertise are illustrated here. The backstory of Historic New England as a social and cultural historian specializing in New England’s material cul- (HNE) itself is intriguing and worth relaying. ture, and my own knowledge of European art, have dovetailed to offer visitors William Sumner Appleton (1874–1947) was a lifelong resident of Bos- some fresh insights. ton and also America’s first full-time professional preservationist. In 1910, he Beyond the research we have undertaken, another joy has been watch- founded the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, now ing the artworks emerge from conservation treatments that have them looking known as Historic New England. For the next 37 years, Appleton led and their best again. All of the paintings have been well cared for over the years, but inspired the rapidly growing organization. He defined its purpose; persuaded, it’s only natural — especially in historic houses — that varnishes begin to yel- charmed, and occasionally hectored the membership; raised money (some- low and nicks appear in a frame’s carving. -

“The Humble, Though More Profitable Art”

“THE HUMBLE, THOUGH MORE PROFITABLE ART”: PANORAMIC SPECTACLES IN THE AMERICAN ENTERTAINMENT WORLD, 1794- 1850 by Nalleli Guillen A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Spring 2018 © 2018 Nalleli Guillen All Rights Reserved “THE HUMBLE, THOUGH MORE PROFITABLE ART”: PANORAMIC SPECTACLES IN THE AMERICAN ENTERTAINMENT WORLD, 1794- 1850 by Nalleli Guillen Approved: __________________________________________________________ Arwen P. Mohun, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of History Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Katherine C. Grier, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Rebecca L. Davis, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ David Suisman, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

January 2018

NEWS-LETTER DEDHAM HISTORICAL SOCIETY & MUSEUM PO BOX 215 612 HIGH STREET DEDHAM MA 02027-0215 Tel: 781-326-1385 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.DedhamHistorical.org Library Hours: by appointment; Museum Hours: Tuesday – Friday 12 pm – 4 pm Both are open even-dated Saturdays: 1 pm – 4 pm January 2018 DINING IN DEDHAM EXHIBIT OPENS JAN. 30 The old saying that "we are what we eat" holds true for the past as well as the present. The Society's new "Dining in Dedham" exhibit looks back on Dedham's culinary history, exploring what our ancestors ate, how they prepared it, and where they dined. From the earliest settlers eating by the kitchen fireplace to the arrival of fast-food chains in the 1950s, "Dining in Dedham" tells this delectable story through photographs, menus, old cookware, and other artifacts from the Society's collection. The exhibit opens January 30 and runs through 2018. So drop in for a taste of Dedham's past! WINTER/SPRING LECTURE SERIES KICKS OFF JANUARY 28 Our 2018 lecture series has something for everyone. On Sunday January 28 at 2 PM, conservator Christine Thompson provides an update on the conservation treatment of the DHS 1763 Act of Parliament Clock. The clock was donated to First Church by Samuel Dexter in 1764. It was removed from the church walls during renovation in 1829 and placed in storage until it was donated to the Society in 1890. It is thought to be one of only three clocks of this type in the United States. -

May 16, 2013 Free

VOLUME 37, NUMBER 27 MAY 16, 2013 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY Artistic Journeys Benjamin Champney, ‘Dean’ of the White Mountain school Page 2 Valley Feature Behind the scenes at Riverstones Bake Shop Page 3 On the Links “New Boys” take the lead at Wentworth Page 19 A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH Artistic Journeys By Cynthia Melendy, Ph.D. State Museum. For those who remark, “Who needs another “A great portion of my art museum?” the answer lies life has been spent in North here, once the artists’ umbrel- Conway and my thoughts la mind is opened. turn pleasantly to that place,” Then, it is always worth- wrote Benjamin Champney in while returning to former his memoirs of his life in Eu- haunts close to home to see rope, North Conway, and the how artists and their friends woods. He is considered the have grown over the seasons. ‘Dean’ of the White Mountain There is always a fresh sur- School of Art, and takes his prise and a welcome regenera- place as the leader of artists in tion when it comes to art. Just the last 150 years of art in the wait a while. Mount Washington Valley. One case in point is the No doubt Champney is a Mount Washington Valley hero to many, and the morn- Arts Association, which is ing the rains came this week, collaborating with the Met to I spent some time in the warm display members’ work in the bluebird skies tracing the Downstairs Gallery as well as march of Spring across the the Upstairs Gallery of the Valley and the Mountains. -

An Interview with the Curators of Thomas Cole's Journey

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: William L. Coleman, “An Interview with the Curators of Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1658. An Interview with the Curators of Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings William L. Coleman, Associate Curator of American Art, The Newark Museum Fig. 1. Cole's Course of Empire in its immersive installation When The Metropolitan Museum of Art hosts an exhibition of early American art, it is by definition an important moment for our field because of the institution’s enviable success at drawing a broad audience to its shows. When that museum uses its considerable clout to gather major international loans that tell a fuller story than any previous exhibition has been able to do of the transatlantic existence of one of the most influential of American artists, it is only more so. Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings marks a turning point for early American art in the popular consciousness, both at home and abroad, by challenging the nativism and conservatism that surrounds narratives of that most marketable and yet most fraught of Americanist brand names: “Hudson River School.” In so doing, it contributes to a moment of transatlantic American landscape exhibitions such as the Detroit Institute of Arts’ Frederic Church: A Painter’s Pilgrimage1 and my own institution’s recent The Rockies and the Alps: Bierstadt, Calame, and the Romance of the Mountains.2 The editors of Panorama asked me, as a nearby Cole specialist with a keen interest in this project but not a participant in it, to interview the cocurators for the benefit of the journal’s readership. -

Seeing in Stereo: Albert Bierstadt and the Stereographic Landscape

Kirsten M. Jensen Seeing in Stereo: Albert Bierstadt and the Stereographic Landscape Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 2 (Autumn 2013) Citation: Kirsten M. Jensen, “Seeing in Stereo: Albert Bierstadt and the Stereographic Landscape,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 2 (Autumn 2013), http://www.19thc- artworldwide.org/autumn13/jensen-on-albert-bierstadt-and-the-stereographic-landscape. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Jensen: Seeing in Stereo: Albert Bierstadt and the Stereographic Landscape Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 2 (Autumn 2013) Seeing in Stereo: Albert Bierstadt and the Stereographic Landscape by Kirsten M. Jensen We call the attention of admirers of photographs to a series of views and studies taken in the White Mountains, published by Bierstadt Brothers of New Bedford, Mass. The artistic taste of Mr. Albert Bierstadt, who selected the points of view, is apparent in them. No better photographs have been published in this country. —The Crayon (January 1861)[1] In 1860, Charles and Edward Bierstadt, brothers of the landscape painter Albert, published a small compilation of stereographic views complete with prismatic viewing lenses, titled Stereoscopic Views Among the Hills of New Hampshire.[2] As the passage above indicates, Albert was closely involved in their new commercial venture, and his collaboration with his brothers had been publicized earlier in the Cosmopolitan Art Journal which noted, “Bierstadt . has gone into the White Mountain region to sketch, and to experiment photographically, along with his brother, a photographist of eminence.”[3] Bierstadt’s sketching and painting activities in the White Mountains were documented by a stereograph his brothers took of him working en plein air (fig.