Analysis of Dutch Master Paintings with Convolutional Neural Networks Steven J. Frank and Andrea M. Frank in Less Than a Decade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn 1606-1669 REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN, born 15 July er (1608-1651), Govaert Flinck (1615-1660), and 1606 in Leiden, was the son of a miller, Harmen Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), worked during these Gerritsz. van Rijn (1568-1630), and his wife years at Van Uylenburgh's studio under Rem Neeltgen van Zuytbrouck (1568-1640). The brandt's guidance. youngest son of at least ten children, Rembrandt In 1633 Rembrandt became engaged to Van was not expected to carry on his father's business. Uylenburgh's niece Saskia (1612-1642), daughter Since the family was prosperous enough, they sent of a wealthy and prominent Frisian family. They him to the Leiden Latin School, where he remained married the following year. In 1639, at the height of for seven years. In 1620 he enrolled briefly at the his success, Rembrandt purchased a large house on University of Leiden, perhaps to study theology. the Sint-Anthonisbreestraat in Amsterdam for a Orlers, Rembrandt's first biographer, related that considerable amount of money. To acquire the because "by nature he was moved toward the art of house, however, he had to borrow heavily, creating a painting and drawing," he left the university to study debt that would eventually figure in his financial the fundamentals of painting with the Leiden artist problems of the mid-1650s. Rembrandt and Saskia Jacob Isaacsz. van Swanenburgh (1571 -1638). After had four children, but only Titus, born in 1641, three years with this master, Rembrandt left in 1624 survived infancy. After a long illness Saskia died in for Amsterdam, where he studied for six months 1642, the very year Rembrandt painted The Night under Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), the most impor Watch (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). -

The Frick Collection, New York Works from the Permanent Collection

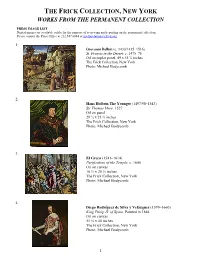

THE FRICK COLLECTION, NEW YORK WORKS FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION PRESS IMAGE LIST Digital images are available solely for the purpose of reviewing and reporting on the permanent collection. Please contact the Press Office at 212.547.6844 or [email protected]. 1. Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430/1435–1516) St. Francis in the Desert, c. 1475–78 Oil on poplar panel, 49 x 55 ⅞ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 2. Hans Holbein The Younger (1497/98–1543) Sir Thomas More, 1527 Oil on panel 29 ½ x 23 ¾ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 3. El Greco (1541–1614) Purification of the Temple, c. 1600 Oil on canvas 16 ½ x 20 ⅝ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 4. Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599–1660) King Philip IV of Spain, Painted in 1644 Oil on canvas 51 ⅛ x 40 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 1 5. Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) Officer and Laughing Girl, c. 1657 Oil on canvas 19 ⅞ x 18 ⅛ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 6. Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606–1669) Self-Portrait, dated 1658 Oil on canvas 52 ⅝ x 40 ⅞ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 7. Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834–1917) The Rehearsal, 1878–79 Oil on canvas 18 ¾ x 24 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 8. Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) The Meeting (one panel in the series called The Progress of Love), 1771–73 Oil on canvas 125 x 96 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 2 9. -

Rembrandt Self Portraits

Rembrandt Self Portraits Born to a family of millers in Leiden, Rembrandt left university at 14 to pursue a career as an artist. The decision turned out to be a good one since after serving his apprenticeship in Amsterdam he was singled out by Constantijn Huygens, the most influential patron in Holland. In 1634 he married Saskia van Uylenburgh. In 1649, following Saskia's death from tuberculosis, Hendrickje Stoffels entered Rembrandt's household and six years later they had a son. Rembrandt's success in his early years was as a portrait painter to the rich denizens of Amsterdam at a time when the city was being transformed from a small nondescript port into the The Night Watch 1642 economic capital of the world. His Rembrandt painted the large painting The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq historical and religious paintings also between 1640 and 1642. This picture was called De Nachtwacht by the Dutch and The gave him wide acclaim. Night Watch by Sir Joshua Reynolds because by the 18th century the picture was so dimmed and defaced that it was almost indistinguishable, and it looked quite like a night scene. After it Despite being known as a portrait painter was cleaned, it was discovered to represent broad day—a party of musketeers stepping from a Rembrandt used his talent to push the gloomy courtyard into the blinding sunlight. boundaries of painting. This direction made him unpopular in the later years of The piece was commissioned for the new hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the musketeer branch of his career as he shifted from being the the civic militia. -

The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3Rd Ed

Govaert Flinck (Kleve 1615 – 1660 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Govaert Flinck” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/govaert- flinck/ (accessed September 27, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Govaert Flinck Page 2 of 8 Govaert Flinck was born in the German city of Kleve, not far from the Dutch city of Nijmegen, on 25 January 1615. His merchant father, Teunis Govaertsz Flinck, was clearly prosperous, because in 1625 he was appointed steward of Kleve, a position reserved for men of stature.[1] That Flinck would become a painter was not apparent in his early years; in fact, according to Arnold Houbraken, the odds were against his pursuit of that interest. Teunis considered such a career unseemly and apprenticed his son to a cloth merchant. Flinck, however, never stopped drawing, and a fortunate incident changed his fate. According to Houbraken, “Lambert Jacobsz, [a] Mennonite, or Baptist teacher of Leeuwarden in Friesland, came to preach in Kleve and visit his fellow believers in the area.”[2] Lambert Jacobsz (ca. 1598–1636) was also a famous Mennonite painter, and he persuaded Flinck’s father that the artist’s profession was a respectable one. Around 1629, Govaert accompanied Lambert to Leeuwarden to train as a painter.[3] In Lambert’s workshop Flinck met the slightly older Jacob Adriaensz Backer (1608–51), with whom he became lifelong friends. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Major Rembrandt Portrait Painting on Loan to the Wadsworth from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Kim Hugo, (860) 838-4082 [email protected] Image file to accompany publicity of this announcement will be available for download at http://press.thewadsworth.org. Email to request login credentials. Major Rembrandt Portrait Painting on Loan to the Wadsworth from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Hartford, Conn. (January 21, 2020)—Rembrandt’s Titus in a Monk’s Habit (1660) is coming to Hartford, Connecticut. On loan from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the painting will be on view at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art from February 1 through April 30, 2020. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), recognized as one of the most important artists of his time and considered by many to be one of the greatest painters in European history, painted his teenage son in the guise of a monk at a crucial moment in his late career when he was revamping his business as a painter and recovering from bankruptcy. It has been fifty-three years since this painting has been on view in the United States making this a rare opportunity for visitors to experience a late portrait by the Dutch master among the collection of Baroque art at the Wadsworth renowned for its standout paintings by Rembrandt’s southern European contemporaries, Zurbarán, Oratio Gentileschi, and Caravaggio. While this painting has been infrequently seen in America, it exemplifies the dramatic use of light and dark to express human emotion for which Rembrandt’s late works are especially prized. “Titus in a Monk’s Habit is an important painting. It opens questions about the artist’s career, his use of traditional subjects, and the bold technique that has won him enduring fame,” says Oliver Tostmann, Susan Morse Hilles Curator of European Art at the Wadsworth. -

Alex Katz Coca Cola Press Release

Alex Katz Coca-Cola Girls 2 November – 21 December, 2018 Timothy Taylor, London, is pleased to present Coca-Cola Girls, an exhibition of new large-scale paintings by Alex Katz inspired by the eponymous, and iconic, figures from advertising art history. The Coca-Cola Girls were an integral component of the company’s advertising from the 1890’s through to the 1960’s, emanating an ideal of the American woman. Initially, the Coca-Cola Girls were reserved and demure, evolving during WWI, and through the era of the pin-up, to images of empowered service women in uniform, and athletic, care-free, women at leisure. In the context of pre-televised advertising, the wall decals and large-scale billboards depicting these figures made a significant impact on the visual language of the American urban landscape. For Katz, this optimistic figure also encapsulates a valuable notion of nostalgia; “That’s Coca-Cola red, from the company’s outdoor signs in the fifties… you know, the blond girl in the red convertible, laughing with unlimited happiness. It’s a romance image, and for me it has to do with Rembrandt’s ‘The Polish Rider.’ I could never understand that painting but my mother and Frank O’Hara both flipped over it, so I realized I was missing something. They saw it as a romantic figure, riding from the Black Sea to the Baltic.” 1 . The poses captured in these new paintings disclose a sense of balletic movement; a left arm extending upwards, a head twisted to the right, a leg poised on the ball of a foot, or a hand extending to and from nowhere - always glimpsed in a fleeting gesture within a dynamic sequence. -

Rembrandt Van Rijn Dutch / Holandés, 1606–1669

Dutch Artist (Artista holandés) Active Amsterdam / activo en Ámsterdam, 1600–1700 Amsterdam Harbor as Seen from the IJ, ca. 1620, Engraving on laid paper Amsterdam was the economic center of the Dutch Republic, which had declared independence from Spain in 1581. Originally a saltwater inlet, the IJ forms Amsterdam’s main waterfront with the Amstel River. In the seventeenth century, this harbor became the hub of a worldwide trading network. El puerto de Ámsterdam visto desde el IJ, ca. 1620, Grabado sobre papel verjurado Ámsterdam era el centro económico de la República holandesa, que había declarado su independencia de España en 1581. El IJ, que fue originalmente una bahía de agua salada, conforma la zona costera principal de Ámsterdam junto con el río Amstel. En el siglo XVII, este puerto se convirtió en el núcleo de una red comercial de carácter mundial. Gift of George C. Kenney II and Olga Kitsakos-Kenney, 1998.129 Jan van Noordt (after Pieter Lastman, 1583–1633) Dutch / Holandés, 1623/24–1676 Judah and Tamar, 17th century, Etching on laid paper This etching made in Amsterdam reproduces a painting by Rembrandt’s teacher, Pieter Lastman, who imparted his close knowledge of Italian painting, especially that of Caravaggio, to his star pupil. As told in Genesis 38, the twice-widowed Tamar disguises herself to seduce Judah, her unsuspecting father-in-law, whose faithless sons had not fulfilled their marital duties. Tamar conceived twins by Judah, descendants of whom included King David. Judá y Tamar, Siglo 17, Aguafuerte sobre papel acanalado Esta aguafuerte creada en Ámsterdam reproduce una pintura del maestro de Rembrandt, Pieter Lastman, quien impartió su vasto conocimiento de la pintura italiana, en especial la de Caravaggio, a su discípulo estrella. -

Jan Lievens (Leiden 1607 – 1674 Amsterdam)

Jan Lievens (Leiden 1607 – 1674 Amsterdam) © 2017 The Leiden Collection Jan Lievens Page 2 of 11 How To Cite Bakker, Piet. "Jan Lievens." In The Leiden Collection Catalogue. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017. https://www.theleidencollection.com/archive/. This page is available on the site's Archive. PDF of every version of this page is available on the Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. Archival copies will never be deleted. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. Jan Lievens was born in Leiden on 24 October 1607. His parents were Lieven Hendricxsz, “a skillful embroiderer,” and Machtelt Jansdr van Noortsant. 1 The couple would have eight children, of whom Jan and Dirck (1612–50/51) would become painters, and Joost (Justus), the eldest son, a bookseller. 2 In 1632 Joost married an aunt of the painter Jan Steen (1625/26–79). 3 At the age of eight, Lievens was apprenticed to Joris van Schooten (ca. 1587–ca. 1653), “who painted well [and] from whom he learned the rudiments of both drawing and painting.” 4 According to Orlers, Lievens left for Amsterdam two years later in 1617 to further his education with the celebrated history painter Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), “with whom he stayed for about two years making great progress in art.” 5 What impelled his parents to send him to Amsterdam at such a young age is not known. When he returned to Leiden in 1619, barely twelve years old, “he established himself thereafter, without any other master, in his father’s house.” 6 In the years that followed, Lievens painted large, mostly religious and allegorical scenes. -

My Favourite Painting Monty Don a Woman Bathing in a Streamby

Source: Country Life {Main} Edition: Country: UK Date: Wednesday 16, May 2018 Page: 88 Area: 559 sq. cm Circulation: ABC 41314 Weekly Ad data: page rate £3,702.00, scc rate £36.00 Phone: 020 7261 5000 Keyword: Paradise Gardens My favourite painting Monty Don A Woman Bathing in a Stream by Rembrandt Monty Don is a writer, gardener and television presenter. His new book Paradise Gardens is out now, published by Two Roads i My grandfather took me to an art gallery every school holidays and, as my education progressed, we slowly worked our way through the London collections. Rembrandt, he told me, was the greatest artist who had ever lived. I nodded, but was uncertain on what to look for that would confirm that judgement. Then I saw this painting and instantly knew. The subject-almost certainly Rembrandt's common-law wife, Hendrickje Stoffels— is not especially beautiful nor has a body or demeanour that might command especial attention. But, as she lifts the hem of her shift to wade in the water, she is made transcendent by Rembrandt's genius. In this, the simplest of moments by an ordinary person in a painting that is hardly more than a sketch, Rembrandt has captured human love at its most 1 intimate and tender. And there is no A Woman Bathing in a Stream, 1654, by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-69), 24 /4in 1 more worthy subject than that ? by 18 /2in, National Gallery, London John McEwen comments on^4 Woman Bathing in a Stream Geertje Dircx, Titus's nursemaid, became her church. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Further Battles for the Lisowczyk (Polish Rider) by Rembrandt

Originalveröffentlichung in: Artibus et Historiae 21 (2000), Nr. 41, S. 197-205 ZDZISLAW ZYGULSKI, JR. Further Battles for the Lisowczyk (Polish Rider) by Rembrandt Few paintings included among outstanding creations of chaser was an outstanding American collector, Henry Clay modern painting provoke as many disputes, polemics and Frick, king of coke and steel who resided in Pittsburgh and passionate discussions as Rembrandt's famous Lisowczyk, since 1920 in New York where, in a specially designed build 1 3 which is known abroad as the Polish Rider . The painting was ing, he opened an amazingly beautiful gallery . The transac purchased by Michat Kazimierz Ogihski, the grand hetman of tion, which arouse public indignation in Poland, was carried Lithuania in the Netherlands in 1791 and given to King out through Roger Fry, a writer, painter and art critic who occa Stanislaus Augustus in exchange for a collection of 420 sionally acted as a buyer of pictures. The price including his 2 guldens' worth of orange trees . It was added to the royal col commission amounted to 60,000 English pounds, that was lection in the Lazienki Palace and listed in the inventory in a little above 300,000 dollars, but not half a million as was 1793 as a "Cosaque a cheval" with the dimensions 44 x 54 rumoured in Poland later. inch i.e. 109,1 x 133,9 cm and price 180 ducats. In his letter to the King, Hetman Ogihski called the rider, The subsequent history of the painting is well known. In presented in the painting "a Cossack on horseback".