Raking Over the Asylum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (14MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Politics, Pleasures and the Popular Imagination: Aspects of Scottish Political Theatre, 1979-1990. Thomas J. Maguire Thesis sumitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Glasgow University. © Thomas J. Maguire ProQuest Number: 10992141 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10992141 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Friday 8 March, 2019 BBC One Scotland BBC Scotland BBC Radio Scotland

BBC WEEK 10 Programme Information Saturday 2 – Friday 8 March, 2019 BBC One Scotland BBC Scotland BBC Radio Scotland Hilda McLean Jim Gough Julie Whiteside BBC Alba - Isabelle Salter @BBCScotComms THIS WEEK’S HIGHLIGHTS TELEVISION & RADIO / BBC WEEK 10 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ SATURDAY 2 MARCH Tutti Frutti, Ep 1/6 TV HIGHLIGHT BBC Scotland SUNDAY 3 MARCH Inside Central Station NEW BBC Scotland MONDAY 4 MARCH Yes/No – Inside The Indyref NEW BBC Scotland TUESDAY 5 MARCH Test Drive (Tuesday-Thursday) BBC Scotland _____________________________________________________________________________ BBC Scotland EPG positions for viewers in Scotland: Freeview & YouView 115 HD / 9 SD Sky 115 Freesat 106 Virgin Media 108 BBC Scotland, BBC One Scotland, BBC ALBA and BBC Radio Scotland are also available on the BBC iPlayer bbc.co.uk/iplayer EDITORIAL 2019 / BBC WEEK 10 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ TUTTI FRUTTI RETURNS TO TV – NEW BBC SCOTLAND CHANNEL TO AIR CULT DRAMA SERIES Tutti Frutti, BBC Scotland, from Saturday 2 March, 9.30-10.30pm After more than 30 years, critically-acclaimed drama, Tutti Frutti will make its long-awaited return to TV screens when the six-part series is shown again on the new BBC Scotland channel from Saturday 2 March. Written by Scots artist and playwright John Byrne, Tutti Frutti followed the fortunes of rock and roll band The Majestics who reform to play a 25th anniversary tour. Starring a stellar cast including Robbie Coltrane, Emma Thompson, Maurice Roeves, Richard Wilson and Katy Murphy, Tutti Frutti made its debut in 1987, achieving cult TV status before it toured as a sell-out stage National Theatre of Scotland stage show. -

John Byrne's Scotland Paul Elliott, University of Worcester

Its Only Rock and Roll: John Byrne’s Scotland Paul Elliott, University of Worcester …I was brought up in Ferguslie Park housing scheme and found myself at the age of fourteen or so rejoicing in that fact and not really understanding why…Only later did I realise that I had been handed the greatest gift a budding painter/playwright could ever have…an enormous ‘treasure trove’ of language, oddballs, crooks, twisters, comics et al…into which I could dip a hand and pull out a mittful of gold dust. (Byrne 2014: 23) John Patrick Byrne was born six days into 1940 and grew up in the Ferguslie Park area of Glasgow. His father earned a living through a series of laboring and manual jobs and his mother was an usherette at the Moss Park Picture House. Byrne took to painting and drawing from an early age and recounts his mother stating that he began drawing in the pram as she wheeled him around the housing estate where they lived. As evidenced by the quote above, Byrne constantly drew on the people he met and saw in his early childhood for his art, and much of his later work can be seen to reflect this child-like vision of the world. When he was in his late childhood, Byrne’s mother was diagnosed with schizophrenia and taken to the Riccartsbar Mental Hospital in Paisley. This had an enormous impact on the young artist’s development and his creative output would be peppered with images of feminine abandonment and women with fragile mental states. -

4 January 2013 Programme Information, Television & Radio BBC Scotland Press Office Bbc.Co.Uk/Mediacentre Bbc.Co.Uk/Iplayer

BBC WEEKS 52 & 1, 22-28 December 2012 29 December 2012 – 4 January 2013 Programme Information, Television & Radio BBC Scotland Press Office bbc.co.uk/mediacentre bbc.co.uk/iplayer THIS WEEK’S HIGHLIGHTS TELEVISION & RADIO / BBC WEEKS 52 & 1 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ SUNDAY 23 DECEMBER Watching Ourselves: Swashbuckled, Prog 1/4 NEW BBC One Scotland MONDAY 24 DECEMBER – CHRISTMAS EVE Christmas Celebration NEW BBC One Scotland Old MacDonald’s Farm NEW BBC Two Scotland Seo am Pleana/Island Flying NEW BBC ALBA Oidhche Naomh/Christmas Eve Service NEW BBC ALBA Past Lives NEW BBC Radio Scotland Watchnight Service NEW BBC Radio Scotland TUESDAY 25 DECEMBER – CHRISTMAS DAY The Band From Rockall NEW BBC ALBA Rockettes NEW BBC ALBA Stark Talk Christmas Special with Katherine Grainger NEW BBC Radio Scotland My Christmas in Five Books NEW BBC Radio Scotland Christmas at The Stand NEW BBC Radio Scotland Christmas Classics NEW BBC Radio Scotland Edith Bowman’s Album Show BBC Radio Scotland – The Best of Guests NEW THURSDAY 27 DECEMBER The Scottish National Trail: BBC Two Scotland An Adventure Show Special, Prog 1/2 NEW John Beattie – 17 Days in London NEW BBC Radio Scotland The Strange Case of Dr Hyde NEW BBC Radio Scotland FRIDAY 28 DECEMBER The Scottish National Trail: BBC Two Scotland An Adventure Show Special, Prog 2/2 NEW Michael Marra: All Will be Well NEW BBC Two Scotland The Kitchen Café – An International Feast NEW BBC Radio Scotland Dan McDuff is -

Raking Over the Asylum: the Television Drama of Donna Franceschild

Raking over the Asylum: the television drama of Donna Franceschild Jonathan Murray, Edinburgh College of Art Introduction American-born dramatist Donna Franceschild is a notably important creative figure within contemporary Scottish screen cultures. She was possibly the most prolific television writer working consistently with Scottish subject matter and from a Scottish production base during the 1990s and early 2000s. Franceschild wrote no fewer than three standalone dramas – Bobbin’ and Weavin’ (1991), And the Cow Jumped Over the Moon (1991), Donovan Quick (2000) – and four multipart serials – Takin’ Over the Asylum (1994), A Mug’s Game (1996), Eureka Street (1999), The Key (2003) – during the period in question. Much of that work attracted substantial critical acclaim when first broadcast. Takin’ Over the Asylum won the 1995 BAFTA award for Best Drama Serial, and Franceschild also secured that year’s Royal Television Society Writer’s Award for the same work; Donovan Quick was nominated for the Best Single Drama BAFTA award six years later (IMDb 2017). Some 1990s press commentators accordingly lauded Franceschild as ‘one of the real television discoveries of the decade’ (Clarke 1996), a judgement that endured into the new century. The Key was included in the British Film Institute’s May 2010 Second Coming: the Rebirth of TV Drama retrospective season of recent British television writing as an example of ‘the kind of ambitious, radical work long assumed dead on British television’ (Duguid 2010a: 53; see also Duguid 2010b). Moreover, Franceschild’s screenwriting constitutes only one strand of her creative practice. Since first establishing a sustained physical and cultural connection with Scotland via a short-term appointment as Creative Writing Fellow at the Universities of Glasgow and Strathclyde in 1983 (McGinty 1994; Summers 1995), she has also written and seen produced 8 theatre plays and 14 radio dramas. -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 26 June – 2 July 2021

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 26 June – 2 July 2021 Page 1 of 11 SATURDAY 26 JUNE 2021 Patrick Wright investigates how artists pioneered the creation show about shame and guilt. of the first effective forms of military camouflage during the Each week Stephen invites a different eminent guest into his SAT 00:00 James Follett - Earthsearch (b00cfzsp) First World War. virtual confessional box to make three 'confessions' . This is a Earthsearch I Producer: John Goudie cue for some remarkable storytelling, and surprising insights. 10. Earthfall First broadcast on BBC radio 4 in August 2002. We’re used to hearing celebrity interviews, where stars are Despite the difficulties put in their way by the two guardian SAT 03:00 Inspector Resnick (b043x39r) persuaded to show off about their achievements and talk about 'Angels', the crew of the Challenger have found Paradise. Cutting Edge their proudest moments. Stephen's not interested in that. He It's an earth-like planet originally discovered by the second- Episode 3 doesn’t want to know what his guests are proud of, he wants to generation crew. However, the 'Angels' are by no means The brutal death of a ward sister intensifies DI Charlie know what they’re ashamed of. That’s surely the way to find out beaten... Resnick's search for the hospital assailant. what really makes a person tick. Stephen and his guest reflect Starring Sean Arnold. Tom Georgeson stars as jazz-loving Detective Inspector Charlie with empathy and humour on why we get embarrassed, where Conclusion of James Follett's ten-part adventure serial in time Resnick. -

Table of Membership Figures For

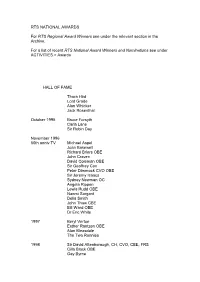

RTS NATIONAL AWARDS For RTS Regional Award Winners see under the relevant section in the Archive. For a list of recent RTS National Award Winners and Nominations see under ACTIVITIES > Awards HALL OF FAME Thora Hird Lord Grade Alan Whicker Jack Rosenthal October 1995 Bruce Forsyth Carla Lane Sir Robin Day November 1996 60th anniv TV Michael Aspel Joan Bakewell Richard Briers OBE John Craven David Coleman OBE Sir Geoffrey Cox Peter Dimmock CVO OBE Sir Jeremy Isaacs Sydney Newman OC Angela Rippon Lewis Rudd OBE Naomi Sargant Delia Smith John Thaw CBE Bill Ward OBE Dr Eric White 1997 Beryl Vertue Esther Rantzen OBE Alan Bleasdale The Two Ronnies 1998 Sir David Attenborough, CH, CVO, CBE, FRS Cilla Black OBE Gay Byrne David Croft OBE Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly Verity Lambert James Morris 1999 Sir Alistair Burnet Yvonne Littlewood MBE Denis Norden CBE June Whitfield CBE 2000 Harry Carpenter OBE William G Stewart Brian Tesler CBE Andrea Wonfor In the Regions 1998 Ireland Gay Byrne Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly James Morris 1999 Wales Vincent Kane OBE Caryl Parry Jones Nicola Heywood Thomas Rolf Harris AM OBE Sir Harry Secombe CBE Howard Stringer 2 THE SOCIETY'S PREMIUM AWARDS The Cossor Premium 1946 Dr W. Sommer 'The Human Eye and the Electric Cell' 1948 W.I. Flach and N.H. Bentley 'A TV Receiver for the Home Constructor' 1949 P. Bax 'Scenery Design in Television' 1950 Emlyn Jones 'The Mullard BC.2. Receiver' 1951 W. Lloyd 1954 H.A. Fairhurst The Electronic Engineering Premium 1946 S.Rodda 'Space Charge and Electron Deflections in Beam Tetrode Theory' 1948 Dr D. -

BBC WEEK 27 Programme Information Saturday 29 June – Friday 5 July 2019 BBC One Scotland BBC Scotland BBC Radio Scotland

BBC WEEK 27 Programme Information Saturday 29 June – Friday 5 July 2019 BBC One Scotland BBC Scotland BBC Radio Scotland Hilda McLean Jim Gough Julie Whiteside BBC Alba – Isabelle Salter THIS WEEK’S HIGHLIGHTS TELEVISION & RADIO / BBC WEEK 27 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ SATURDAY 29 JUNE Takin’ Over The Asylum, Ep 1/6 TV HIGHLIGHT BBC Scotland TUESDAY 2 JULY Children of the Devolution LAST IN THE SERIES BBC Scotland _____________________________________________________________________________ BBC Scotland EPG positions for viewers in Scotland: Freeview & YouView 115 HD / 9 SD Sky 115 Freesat 106 Virgin Media 108 BBC Scotland, BBC One Scotland and BBC ALBA are available on the BBC iPlayer bbc.co.uk/iplayer BBC Radio Scotland is also available on BBC Sounds bbc.co.uk/sounds SATURDAY 29 JUNE TELEVISION & RADIO HIGHLIGHTS / BBC WEEK 27 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Takin’ Over The Asylum, Ep 1/6 TV HIGHLIGHT Saturday 29 June BBC Scotland, 9.00-10.00pm Another chance to watch critically acclaimed, BAFTA award-winning, drama series Takin’ Over The Asylum. Set in a hospital radio station in a Glasgow psychiatric hospital, the six-part series first aired in 1994 and starred David Tennant and Ken Stott. Stott stars as Eddie McKenna, a double-glazing salesman who moonlights as a DJ for hospital radio in the St Jude’s Hospital mental asylum. There, he nurtures close friendships with the patients including Campbell (Tennant) a manic depressive whom he shares a dream to make it onto the commercial radio scene, self-harmer Francine (Katy Murphy), schizophrenic electrical engineer Fergus (Angus Macfadyen) and OCD housewife Rosalie (Ruth McCabe). Campbell's inspired antics promise to bring the commercial radio dream closer, but the pressures of life outside of the hospital begin to tell on Eddie. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Alliteration, America and authorship Citation for published version: Murray, J 2018, 'Alliteration, America and authorship: The television drama of John Byrne', Visual Culture in Britain, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 378-400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14714787.2018.1439768 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/14714787.2018.1439768 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Visual Culture in Britain General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 Jonathan Murray Alliteration, America and Authorship: the Television Drama of John Byrne Abstract Creative polymath John Byrne enjoys a secure and substantial international reputation within the graphic and theatrical arts, and as a seminal figure within late-twentieth and early-twenty-first century Scottish culture. Yet Byrne’s sustained engagement with screenwriting and screen directing practices between the late 1980s and late 1990s constitutes a critically under-examined aspect of his career to date. Moreover, such neglect is also symptomatic of a wider lack of attention paid to television within the study of modern Scottish culture.