A GIANT of ITS KIND RECOMMENDED: APPROVED: By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

”Shoes”: a Componential Analysis of Meaning

Vol. 15 No.1 – April 2015 A Look at the World through a Word ”Shoes”: A Componential Analysis of Meaning Miftahush Shalihah [email protected]. English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University Abstract Meanings are related to language functions. To comprehend how the meanings of a word are various, conducting componential analysis is necessary to do. A word can share similar features to their synonymous words. To reach the previous goal, componential analysis enables us to find out how words are used in their contexts and what features those words are made up. “Shoes” is a word which has many synonyms as this kind of outfit has developed in terms of its shape, which is obviously seen. From the observation done in this research, there are 26 kinds of shoes with 36 distinctive features. The types of shoes found are boots, brogues, cleats, clogs, espadrilles, flip-flops, galoshes, heels, kamiks, loafers, Mary Janes, moccasins, mules, oxfords, pumps, rollerblades, sandals, skates, slides, sling-backs, slippers, sneakers, swim fins, valenki, waders and wedge. The distinctive features of the word “shoes” are based on the heels, heels shape, gender, the types of the toes, the occasions to wear the footwear, the place to wear the footwear, the material, the accessories of the footwear, the model of the back of the shoes and the cut of the shoes. Keywords: shoes, meanings, features Introduction analyzed and described through its semantics components which help to define differential There are many different ways to deal lexical relations, grammatical and syntactic with the problem of meaning. It is because processes. -

ABSTRACT Beck Boots: the Story of Cowboy Boots in the Texas

ABSTRACT Beck Boots: The Story of Cowboy Boots in the Texas Panhandle and Their Important Role in American Life Tye E. Barrett, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon Jr., Ph.D. Merton McLaughlin moved to the Texas Panhandle and began making cowboy boots in the spring of 1882. Since that time, cowboy boots have been a part of the Texas Panhandle’s, and America’s rich history. In 1921, twin brothers Earl and Bearl Beck purchased McLaughlin’s boot shop. The Beck family has been making cowboy boots in the Texas Panhandle ever since. This thesis seeks not only to present a history of Beck Boots and cowboy boots in the Texas Panhandle, but also suggests that the relationship between bootmakers, like Beck Boots, and the working cowboy has been the center of success to the business of bootmakers and cowboys alike. Because many, like the Beck family, have nurtured this relationship, cowboy boots have become a central theme and important icon in American life. Beck Boots: The Story of Cowboy Boots in the Texas Panhandle and Their Important Role in American Life by Tye E. Barrett, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Barry G. Hankins, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Sara J. Stone, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2010 ___________________________________ J. -

Footwear and Shoemaking in Turku in the Middle Ages and at the Beginning of the Early Modern Period

Janne Harjula Before the Heels Footwear and Shoemaking in Turku in the Middle Ages and at the Beginning of the Early Modern Period Archaeologia Medii Aevi Finlandiae XV Suomen keskiajan arkeologian seura – Sällskapet för medeltidsarkeologi i Finland Janne Harjula Before the Heels Footwear and Shoemaking in Turku in the Middle Ages and at the Beginning of the Early Modern Period Suomen keskiajan arkeologian seura Turku Editorial Board: Anders Andrén, Knut Drake, David Gaimster, Georg Haggrén, Markus Hiekkanen, Werner Meyer, Jussi-Pekka Taavitsainen and Kari Uotila Editor Janne Harjula Language revision Colette Gattoni Layout Jouko Pukkila Cover design Janne Harjula and Jouko Pukkila Published with the kind support of Emil Aaltonen Memorial Fund and Fingrid Plc Cover image Reconstruction of a medieval shoemaker’s workshop. Produced for an exhibition introducing the 15th and 16th centuries. Technical realization: Schweizerisches Waffeninstitut Grandson. Photograph: K. P. Petersen. © 1987 Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte SMPK Berlin. Back cover images Children’s shoes from excavations in Turku. Janne Harjula/Turku Provincial Museum. ISBN: ISSN: 1236-5882 Saarijärven Offset Oy Saarijärvi 2008 5 CONTENTS Preface 9 Introduction 11 Questions and the definition of the study 12 Research history 13 Material and methodology 17 PART I: FOOTWEAR 21 1. SHOE TYPES IN TURKU 21 1.1 One-piece shoes 22 1.1.1 The type definition and research history of one-piece shoes in Turku 22 1.1.2 The number and types of one-piece shoes 22 1.1.2.1 Cutting patterns -

Circus Report, May 24, 1976, Vol. 5, No. 21

M« Miiiifi eiiHS fllljj 5th Year Ma> 2k, 1976 Number 21 Show Folds in Texas An anticipated circus day at San Antonio (Texas) turned out to be a disappointment for fans and show folks alike. In the midst of a steady rain Circus Galaxy folded in that .city on May 9th. Early this year announcements about the circus indicated it would rival the best shows on the road. Phone crews started their San Antonio promotion about two months ago. While they were vague about the show's name they were positive it was a "large tented show" with the best of everything. CFA's who saw the circus at Victoria described it as "a small show" with no show owned equipment. They called it strictly "a drum and organ show" with the Oscarian Family and some Mexican performers. Six performances were scheduled for San Antonio, but prior to the first show, performers were told they (Continued on Page 16) A VAILABLE fOP LIMITED ENGAGEMENTS HOLLYWOOD ELEPHANTS Contact JUDY JACOBSKAYE Suit* 519 • 1680 North Vine Street • Hollywood, California • 90028 Area Code 213 • 462-6001 Page 2 The Circus Report American Continental by MIKE SPORRER The 1976 circus season got off to a big start with the arriv- al of the American Continental Circus at Seattle, Wash. The May 1-5 engagement was sponsored by the Police Officers Guild, that organi- zation's llth annual circus presentation. This year's Bicentennial edition is a colorful one and is well presented. The center ring is new and all three are painted red, white and blue. -

Of 2 BILL ANALYSIS Senate Research Center HCR 151 By

BILL ANALYSIS Senate Research Center H.C.R. 151 By: Bohac (Patrick) International Relations & Trade 5/22/2007 Engrossed AUTHOR'S / SPONSOR'S STATEMENT OF INTENT The State of Texas boasts a richly diverse cultural heritage, and through the years it has adopted a number of tangible representations of that heritage as official symbols. For nearly a century, the cowboy boot has enjoyed a special status as one of the most treasured of Texas icons. Although riding boots date back for centuries, and although ranches first appeared in Texas during the Spanish colonial era, the basic pattern of the cowboy boot was forged in the crucible of the post-Civil War trail drives; between 1866 and 1890, mounted cowboys drove millions of head of Texas cattle to northern and western markets along such famous trails as the Chisholm, Western, and Goodnight-Loving. Boot makers in Texas and Kansas responded to suggestions from those cowboys regarding the design of their footwear, and a slimmer boot with a higher heel, more rounded toe, and rounded, reinforced instep began to be developed. During the course of the 20th century, cowboy boots gained a mass appeal that ultimately extended to foreign lands; this popularity was driven by an enthusiasm for the West that was fostered in the 1920s and 1930s by radio shows and movie serials and in the post-World War II decades by rodeos and dude ranches; the public’s fascination with cowboys and their apparel has also been fired by movie screen idols such as Tom Mix, by entertainers such as Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, and Dale Evans, and, in recent years, by movies such as Urban Cowboy and Silverado. -

When the War Ended in 1945, Europe Turned to the Task of Rebuilding, and Americans Once Again Looked West for Inspiration

When the war ended in 1945, Europe turned to the task of rebuilding, and Americans once again looked west for inspiration. The swagger of the cowboy fitted the victorious mood of the country. Dude ranches were now a destination for even the middle class. Hopalong Cassidy and the puppet cowboy Howdy Doody kept children glued to their televisions, and Nashville’s country music industry produced one ‘rhinestone cowboy’ after another. Westerns were also one of the most popular film genres. As the movie director Dore Schary noted, ‘the American movie screen was dominated by strong, rugged males – the “one punch, one [gun] shot variety”.’43 In this milieu, cowboy boots became increasingly glamorous. Exagger- atedly pointed toes, high-keyed coloured leathers, elaborate appliqué and even actual rhinestone embellishments were not considered excessive. This period has been called the golden age of cowboy boots, and the artistry and imagination expressed in late 1940s and 1950s boot-making is staggering. The cowboy boot was becoming part of costume, a means of dressing up, of playing type. This point was made clear by the popularity of dress-up cowboy clothes, including boots, for children. Indeed, this transformation into costume was becoming the fate of many boots in fashion. Although most boot styles fell out of fashion in the 1950s, in the immediate post-war period a particular form of military footwear did pass into men’s stylish casual dress: the chukka boot, said to have come from India, and its variant, the desert boot. Designed as a low ankle boot with a two to three eyelet closure, chukkas were said to have been worn for comfort by British polo players both on and off the field in India.44 The simple desert boot was based on the traditional chukka but in Cairo during the war it was given a crepe sole and soft suede upper. -

Seasons Change. Quality Endures

SEASONS CHANGE. QUALITY ENDURES. SPRING STYLES 2015 WARWICK AND ROGUE IN WALNUT (PAGE 8) HANDCRAFTED SPRING HAS SPRUNG A LEGACY WORTH CARRYING ON Artic blast. Polar vortex. Snowmageddon—winter these days feels more like a horror movie or disaster flick than a season. But your reward for the cold temps, icy winds and record snowfall is here: our Spring catalog featuring our latest designs perfect for the new year and the new you. With the weather transitioning from cold to warm you need to be prepared for anything. That means having a pair of our shoes with an all-weather Dainite sole. Made of rubber and studded for extra grip without the extra grime that comes with ridging, these soles let you navigate April showers without breaking your stride. Speaking of breaks, spring is a great time for one. If you are out on the open road or hopping on a plane, the styles in our Drivers Collection are comfortable and convenient travel footwear. Available in a variety of designs and colors, there is one For nearly a century we have (or more) to match your destination as well as your personality. PAGE 33 PAGE 14 continued to adhere to our 212-step manufacturing process Enjoy the Spring catalog and the sunnier days ahead. because great craftsmanship cannot and should not be Warm regards, rushed. To that end, during upper sewing, our skilled cutters and sewers still create the upper portion of each shoe by hand using time-tested methods, hand-cut pieces of leather PAUL GRANGAARD and dependable, decades-old President and CEO sewing machines. -

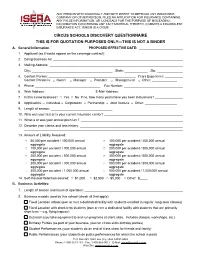

Circus Schools Discovery Questionnaire This Is for Quotation Purposes Only—This Is Not a Binder A

ANY PERSON WHO KNOWINGLY AND WITH INTENT TO DEFRAUD ANY INSURANCE COMPANY OR OTHER PERSON, FILES AN APPLICATION FOR INSURANCE CONTAINING ANY FALSE INFORMATION, OR CONCEALS FOR THE PURPOSE OF MISLEADING, INFORMATION CONCERNING ANY FACT MATERIAL THERETO, COMMITS A FRAUDULENT INSURANCE ACT, WHICH IS A CRIME. CIRCUS SCHOOLS DISCOVERY QUESTIONNAIRE THIS IS FOR QUOTATION PURPOSES ONLY—THIS IS NOT A BINDER A. General Information PROPOSED EFFECTIVE DATE: 1. Applicant (as it would appear on the coverage contract): 2. Doing Business As: 3. Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: 4. Contact Person: Years Experience: Contact Person is: □ Owner □ Manager □ Promoter □ Management □ Other: 5. Phone: Fax Number: 6. Web Address: E-Mail Address: 7. Is this a new business? □ Yes □ No If no, how many years have you been in business? 8. Applicant is: □ Individual □ Corporation □ Partnership □ Joint Venture □ Other: 9. Length of season: 10. Who was your last or is your current insurance carrier? 11. What is or was your annual premium? 12. Describe your claims and loss history: 13. Amount of Liability Required: □ 50,000 per accident / 100,000 annual □ 100,000 per accident / 200,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 100,000 per accident / 300,000 annual □ 200,000 per accident / 300,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 200,000 per accident / 500,000 annual □ 300,000 per accident / 500,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 300,000 per accident / 300,000 annual □ 500,000 per accident / 500,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 300,000 per accident / 1,000,000 annual □ 500,000 per accident / 1,000,000 annual aggregate aggregate 14. Self-Insured Retention desired: □ $1,000 □ $2,500 □ $5,000 □ Other: $ B. -

Boots with a Soul

BOOTSH anWdmadIe iTn THexas , UASA SOUL “THOSE WHO LOVE THEIR AB BOOTS LIVE LIFE THE SAME WAY WE MAKE OUR BOOTS: ROOTED IN TEXAS TRADITION AND STYLE. THEY RIDE, WORK, TAILGATE, TWO-STEP, COMPETE AND DO EVERYTHING IN BETWEEN IN THESE BOOTS.” BY SIMONA DIALE nderson Bean was created in medium price range. Their women, kids and babies. Boots for 1987 by the own ers of Rios independent label has grown for a full lifestyle, and boots built Aof Mercedes boots in order almost 30 years to include one-of- upon the knowledge and expertise to offer a high quality, all-leather a-kind custom boots, plus a full of over 150 years of exceptional cowboy boot that would fall in the line of stock boots for men, boot making. FROM OUR CORPORATE PARNERS e l Trainor Evans and Ryan Vaughan a i D a n o m i S y b made on themselves and they were y h p a r either broke or sold out. We had g o t o saved every nickel that we’d ever h P made and when things started to © come apart, we had the money to pay inventory. We did it because we were careful, not because we were brilliant, and we had that advantage. This is not “I come f rom six generations of an easy business. It takes a lot of cash cattle ranchers,” says Evans, co- and foresight and you need to spend owner of Anderson Bean and Rios less than what you make. When we of Mercedes. -

6592 Ezra & Wheatley.Indd

Shoe Reels 66592_Ezra592_Ezra & WWheatley.inddheatley.indd i 222/10/202/10/20 110:130:13 AAMM Film and Fashions Series editor Pamela Church Gibson Th is series explores the complex and multi-faceted relationship between cinema, fashion and design. Intended for all scholars and students with an interest in fi lm and in fashion itself, the series not only forms an important addition to the existing literature around cinematic costume, but advances the debates by moving them forward into new, unexplored territory and extending their reach beyond the parameters of Western cinema alone. edinburghuniversitypress.com/series/faf 66592_Ezra592_Ezra & WWheatley.inddheatley.indd iiii 222/10/202/10/20 110:130:13 AAMM Shoe Reels The History and Philosophy of Footwear in Film Edited by Elizabeth Ezra and Catherine Wheatley 66592_Ezra592_Ezra & WWheatley.inddheatley.indd iiiiii 222/10/202/10/20 110:130:13 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutt ing-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matt er and organisation Elizabeth Ezra and Catherine Wheatley, 2020 © the chapters their several authors, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd Th e Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 12/1 4 Arno and Myriad by IDSUK (Dataconnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5140 6 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5142 0 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5143 7 (epub) Th e right of the contributors to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. -

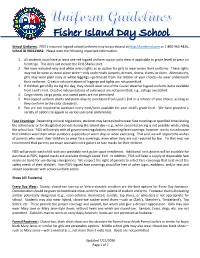

2020-2021 School Uniforms

Fisher Island Day School School Uniforms: FIDS’s required, logoed school uniforms may be purchased at http://landsend.com or 1-800-963-4816, School ID 900123852. Please note the following important information: 1. All students must have at least one red logoed uniform top (or polo dress if applicable to grade level) to wear on field trips. This does not include the FIDS Sharks shirt. 2. We have included navy and white micro tights as an option for girls to wear under their uniforms. These tights may not be worn as stand-alone attire—only underneath jumpers, dresses, shorts, skorts, or skirts. Alternatively, girls may wear plain navy or white leggings—purchased from the retailer of your choice—to wear underneath their uniforms. Creative interpretations of leggings and tights are not permitted. 3. If children get chilly during the day, they should wear one of the Cooler Weather logoed uniform items available from Land’s End. Creative interpretations of outerwear are not permitted; e.g., college sweatshirt. 4. Cargo shorts, cargo pants, and sweat pants are not permitted. 5. Non-logoed uniform shorts and pants may be purchased from Land’s End or a retailer of your choice, as long as they conform to the color standards. 6. You are not required to purchase every item/color available for your child’s grade level. We have provided a variety of options to appeal to various personal preferences. Face Coverings: Depending on local regulations, students may be required to wear face coverings at specified times during the school year or for designated periods during the school day—e.g., when social distancing is not possible while; riding the school bus. -

Fashionable Boots4

FASHIONABLE BOOTS By Lois Przywitowski In some parts of the country the snow is flying and the trusty galoshes may not be enough to protect your feet from the winter weather. Thankfully, in the Model A era, there were multiple, fashionable, boot styles from which to choose, some of which are shown here. High Cut Boot This sporty 15-inch *The Goodyear Welt high cut boot is a method of features a handy stitching the upper side pocket. The and sole of the shoe soles are genuine together, resulting in Goodyear Welt* the unique leather. The heel is positioning of the topped with rubber. two seams in the The available colors shoe bottom. A are brown and black, hidden seam holds in sizes 2 ½ to 8 in a together the welt, wide width. The the upper, the lining sale price is $4.79. and the insole of the shoe. It is stitched National Bellas Hess, using a Goodyear Winter, 1931-32 Welt Machine. Rugged Outdoor Boot **The Blucher-cut Perhaps you are desirous uses a continuous cut of a simpler outdoor boot. piece of leather for Try these genuine leather the vamp (toe area) Blucher-cut** boots, with and the tongue of the a damp-proof fiber sole. shoe. For ease of Available in brown or getting the shoe on black, sized 2-1/2 to 8, for and off, the eyelet flap only $1.69 stitching ends before National Bellas Hess, crossing the arch area Winter, 1931-32 of the shoe. This allows the entire eyelet flap to open.