1 · the Map and the Development of the History of Cartography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coronado and Aesop Fable and Violence on the Sixteenth-Century Plains

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 2009 Coronado and Aesop Fable and Violence on the Sixteenth-Century Plains Daryl W. Palmer Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Palmer, Daryl W., "Coronado and Aesop Fable and Violence on the Sixteenth-Century Plains" (2009). Great Plains Quarterly. 1203. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1203 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CORONADO AND AESOP FABLE AND VIOLENCE ON THE SIXTEENTH~CENTURY PLAINS DARYL W. PALMER In the spring of 1540, Francisco Vazquez de the killing of this guide for granted, the vio Coronado led an entrada from present-day lence was far from straightforward. Indeed, Mexico into the region we call New Mexico, the expeditionaries' actions were embedded where the expedition spent a violent winter in sixteenth-century Spanish culture, a milieu among pueblo peoples. The following year, that can still reward study by historians of the after a long march across the Great Plains, Great Plains. Working within this context, I Coronado led an elite group of his men north explore the ways in which Aesop, the classical into present-day Kansas where, among other master of the fable, may have informed the activities, they strangled their principal Indian Spaniards' actions on the Kansas plains. -

Planar Maps: an Interaction Paradigm for Graphic Design

CH1'89 PROCEEDINGS MAY 1989 PLANAR MAPS: AN INTERACTION PARADIGM FOR GRAPHIC DESIGN Patrick Baudelaire Michel Gangnet Digital Equipment Corporation Pads Research Laboratory 85, Avenue Victor Hugo 92563 Rueil-Malmaison France In a world of changing taste one thing remains as a foundation for decorative design -- the geometry of space division. Talbot F. Hamlin (1932) ABSTRACT Compared to traditional media, computer illustration soft- Figure 1: Four lines or a rectangular area ? ware offers superior editing power at the cost of reduced free- Unfortunately, with typical drawing software this dual in- dom in the picture construction process. To reduce this dis- terpretation is not possible. The picture contains no manipu- crepancy, we propose an extension to the classical paradigm lable objects other than the four original lines. It is impossi- of 2D layered drawing, the map paradigm, that is conducive ble for the software to color the rectangle since no such rect- to a more natural drawing technique. We present the key angle exists. This impossibility is even more striking when concepts on which the new paradigm is based: a) graphical the four lines are abutting as in Fig. 2. We feel that such a objects, called planar maps, that describe shapes with multi- restriction, counter to the traditional practice of the designer, ple colors and contours; b) a drawing technique, called map is a hindrance to productivity and creativity. In this paper sketching, that allows the iterative construction of arbitrarily we propose a new drawing paradigm that will permit a dual complex objects. We also discuss user interface design is- interpretation of Fig. -

The Portolan, This Is a Bibliographic Listing of Articles and Books Appearing Worldwide on Antique Maps and Globes and the History of Cartography

Journal of the Washington Map Society CONTENTS LISTING Issues 1 – 111 (Fall 1984 - Fall 2021) CONTENTS OF ISSUE 1 - October 10, 1984 ARTICLE Early Cartography of Virginia’s Northern Neck. By Dr. Walter W. Ristow. RECENT PUBLICATIONS A regular feature in The Portolan, this is a bibliographic listing of articles and books appearing worldwide on antique maps and globes and the history of cartography. By Eric W. Wolf SHORTER ITEMS 1. Washington Map Society Meetings, October - November 1984. 2. Exhibitions and Meetings, April 1984 - November 1985. CONTENTS OF ISSUE 2 - December 27, 1984 ARTICLES Globes in the Library of Congress. By Andrew M. Modelski. The Raleigh and Roanoke Exhibit Commemorating the 400th Anniversary of England’s First Colonial Attempt in America. A summary by Jeanne Young of a presentation to the Society by Dr. Helen Wallis. Map Festival: Places and Spaces. A summary by Jeanne Young of a presentation to th e Society by Barbara Adele Fine. Notes on the Medieval Map. By P. J. Mode. SHORTER ITEMS 1. Washington Map Society Meetings, January - March 1985. 2. Exhibitions and Meetings, November 1984 - November 1985. 3. Images of the World: The Atlas Through History. Report on the Library of Congress exhibit and symposium. CONTENTS OF ISSUE 3 - April 8, 1985 ARTICLES Recent Cartobibliographies: A Note on their Format, Purpose and a List. By Eric W. Wolf. Aerial Reconnaissance and Map Making During the Civil War. A summary by Jeanne Young of a presentation to the Society by John Sellers. Cartography at the National Geographic Society. A summary by Jeanne Young of a presentation by Dr. -

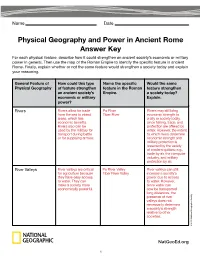

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Texture / Image-Based Rendering Texture Maps

Texture / Image-Based Rendering Texture maps Surface color and transparency Environment and irradiance maps Reflectance maps Shadow maps Displacement and bump maps Level of detail hierarchy CS348B Lecture 12 Pat Hanrahan, Spring 2005 Texture Maps How is texture mapped to the surface? Dimensionality: 1D, 2D, 3D Texture coordinates (s,t) Surface parameters (u,v) Direction vectors: reflection R, normal N, halfway H Projection: cylinder Developable surface: polyhedral net Reparameterize a surface: old-fashion model decal What does texture control? Surface color and opacity Illumination functions: environment maps, shadow maps Reflection functions: reflectance maps Geometry: bump and displacement maps CS348B Lecture 12 Pat Hanrahan, Spring 2005 Page 1 Classic History Catmull/Williams 1974 - basic idea Blinn and Newell 1976 - basic idea, reflection maps Blinn 1978 - bump mapping Williams 1978, Reeves et al. 1987 - shadow maps Smith 1980, Heckbert 1983 - texture mapped polygons Williams 1983 - mipmaps Miller and Hoffman 1984 - illumination and reflectance Perlin 1985, Peachey 1985 - solid textures Greene 1986 - environment maps/world projections Akeley 1993 - Reality Engine Light Field BTF CS348B Lecture 12 Pat Hanrahan, Spring 2005 Texture Mapping ++ == 3D Mesh 2D Texture 2D Image CS348B Lecture 12 Pat Hanrahan, Spring 2005 Page 2 Surface Color and Transparency Tom Porter’s Bowling Pin Source: RenderMan Companion, Pls. 12 & 13 CS348B Lecture 12 Pat Hanrahan, Spring 2005 Reflection Maps Blinn and Newell, 1976 CS348B Lecture 12 Pat Hanrahan, Spring 2005 Page 3 Gazing Ball Miller and Hoffman, 1984 Photograph of mirror ball Maps all directions to a to circle Resolution function of orientation Reflection indexed by normal CS348B Lecture 12 Pat Hanrahan, Spring 2005 Environment Maps Interface, Chou and Williams (ca. -

Reef-Coral Fauna of Carrizo Creek, Imperial County, California, and Its Significance

THE REEF-CORAL FAUNA OF CARRIZO CREEK, IMPERIAL COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE . .By THOMAS WAYLAND VAUGHAN . INTRODUCTION. occur has been determined by Drs . Arnold and Dall to be lower Miocene . The following conclusions seem warranted : Knowledge of the existence of the unusually (1) There was water connection between the Atlantic and interesting coral fauna here discussed dates Pacific across Central America not much previous to the from the exploration of Coyote Mountain (also upper Oligocene or lower Miocene-that is, during the known as Carrizo Mountain) by H . W. Fair- upper Eocene or lower Oligocene . This conclusion is the same as that reached by Messrs. Hill and Dall, theirs, how- banks in the early nineties.' Dr. Fairbanks ever, being based upon a study of the fossil mollusks . (2) sent the specimens of corals he collected to During lower Miocene time the West Indian type of coral Prof. John C. Merriam, at the University of fauna extended westward into the Pacific, and it was sub- California, who in turn sent them to me . sequent to that time that the Pacific and Atlantic faunas There were in the collection representatives of have become so markedly differentiated . two species and one variety, which I described As it will be made evident on subsequent under the names Favia merriami, 2 Stephano- pages that this fauna is much younger than ctenia fairbanksi,3 and Stephanoccenia fair- lower Miocene, the inference as to the date of banksi var. columnaris .4 As the geologic hori- the interoceanic connection given in the fore- zon was not even approximately known at that going quotation must be modified . -

Geography and Atmospheric Science 1

Geography and Atmospheric Science 1 Undergraduate Research Center is another great resource. The center Geography and aids undergraduates interested in doing research, offers funding opportunities, and provides step-by-step workshops which provide Atmospheric Science students the skills necessary to explore, investigate, and excel. Atmospheric Science labs include a Meteorology and Climate Hub Geography as an academic discipline studies the spatial dimensions of, (MACH) with state-of-the-art AWIPS II software used by the National and links between, culture, society, and environmental processes. The Weather Service and computer lab and collaborative space dedicated study of Atmospheric Science involves weather and climate and how to students doing research. Students also get hands-on experience, those affect human activity and life on earth. At the University of Kansas, from forecasting and providing reports to university radio (KJHK 90.7 our department's programs work to understand human activity and the FM) and television (KUJH-TV) to research project opportunities through physical world. our department and the University of Kansas Undergraduate Research Center. Why study geography? . Because people, places, and environments interact and evolve in a changing world. From conservation to soil science to the power of Undergraduate Programs geographic information science data and more, the study of geography at the University of Kansas prepares future leaders. The study of geography Geography encompasses landscape and physical features of the planet and human activity, the environment and resources, migration, and more. Our Geography integrates information from a variety of sources to study program (http://geog.ku.edu/degrees/) has a unique cross-disciplinary the nature of culture areas, the emergence of physical and human nature with pathway options (http://geog.ku.edu/geography-pathways/) landscapes, and problems of interaction between people and the and diverse faculty (http://geog.ku.edu/faculty/) who are passionate about environment. -

The Empirics of New Economic Geography ∗

The Empirics of New Economic Geography ∗ Stephen J Redding LSE, Yale School of Management and CEPR y February 28, 2009 Abstract Although a rich and extensive body of theoretical research on new economic geography has emerged, empirical research remains comparatively less well developed. This paper reviews the existing empirical literature on the predictions of new economic geography models for the distribution of income and production across space. The discussion highlights connections with other research in regional and urban economics, identification issues, potential alternative explanations and possible areas for further research. Keywords: New economic geography, market access, industrial location, multiple equilibria JEL: F12, F14, O10 ∗This paper was produced as part of the Globalization Programme of the ESRC-funded Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics. Financial support under the European Union Research Training grant MRTN-CT-2006-035873 is also gratefully acknowledged. I am grateful to a number of co-authors and colleagues for insight, discussion and comments, including in particular Tony Venables and Gilles Duranton, and also Guy Michaels, Henry Overman, Esteban Rossi-Hansberg, Peter Schott, Daniel Sturm and Nikolaus Wolf. I bear sole responsibility for the opinions expressed and any errors. yDepartment of Economics, London School of Economics, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom. Tel: + 44 20 7955 7483, Fax: + 44 20 7955 7595, Email: s:j:redding@lse:ac:uk. Web: http : ==econ:lse:ac:uk=staff=sredding=. 1 1 Introduction Over the last two decades, the uneven distribution of economic activity across space has received re- newed attention with the emergence of the “new economic geography” literature following Krugman (1991a). -

Geography Introduction

Geography Student Handbook CSUS Geography, Fall 2005 Geography Student Handbook contents ONE WELCOME TO GEOGRAPHY Part Welcome Geography Students 1 Reception 2 Keeping the Department Informed 2 Faculty Profiles and Contact Information 3 Maps 4 Campus 4 Bizzini Hall (Classroom Building) 2nd Floor 5 GIS Lab 6 Bio-Ag 7 TWO WHAT IS GEOGRAPHY? 8 Definitions 8 Areas of Geographic Study 9 General Readings in Geography and Teaching 10 THREE YOUR PROGRAM 11 Advising 11 Registration 12 Geography Courses (from Catalog) 13 BA Geography Worksheet (regular tract) 14 BA Geography with Applied Concentration Worksheet 15 Geography Minor Worksheet 16 Liberal Studies with Geography Concentration Worksheet 17 Social Science with Geography Concentration Worksheet 17 General Education Worksheet 18 Plagerism and Academic Dishonesty 19 Readings – Coping with Classes 20 Internships 21 FOUR GEOGRAPHY’S FACILITIES 22 Laboratories 22 The Field 22 GIS Lab 23 Bio-Ag 23 The Bridge 24 Study Abroad 25 Other Facilities 26 FIVE LIFE AFTER CSUS 27 Occupations 27 Graduate School 28 Letter of Reference 29 1 one - welcome to geography “Of all the disciplines, it is geography that has captured the vision of the earth as a whole.” Kenneth Boulding WELCOME GEOGRAPHY STUDENTS! This student handbook provides a way for you to track your degree progress and helps you navigate a path, not only to complete your degree, but to seek a profession in geography or attend graduate school. It serves as a convenient source for general information about the discipline of geography, department and campus resources, and who to contact with various questions. This handbook does not replace the personal one-to-one contact between yourself and your advisor. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

From Columbus to Acosta: Science

FromColumbus to Acosta: Science, Geography,and the New World KarlW. Butzer Departmentof Geography,University of Texasat Austin,Austin, TX 78712, FAX 512/471-5049 Abstract.What is called the Age of Discovery peoples probably put observers with rural evokes imagesof voyages,nautical skills, and backgroundson an equal footingwith those maps. Yet the Europeanencounter with the steeped in traditionalacademic curricula.Last Americasalso led to an intellectualconfronta- butnot least,the essaypoints up the enormity tionwith the naturalhistory and ethnography of the primarydocumentation, compiled by of a "new" world.Contrary to the prevailing these Spanishcontributors during the century view of intellectualstasis, this confrontation after1492, most of it awaitinggeographical re- provokednovel methods of empiricaldescrip- appraisal. tion, organization,analysis, and synthesisas KeyWords: Acosta,Columbus, ethnography, geo- Medievaldeductivism and Classicalontogen- graphicalplanning, gridiron towns, historyof sci- ies proved to be inadequate. This essay ence, landforms,L6pez de Velasco, naturalhistory, demonstrateshow the agentsof thatencoun- New World landscapes, Oviedo, relaciones ter-sailors, soldiers, governmentofficials, geograficas,Renaissance, Sahagun, Spanish geogra- and missionaries-madesense of these new phy. landsand peoples; ithighlights seven method- ological spheres, by examiningthe work of The worldis so vastand beautiful,and containsso exemplaryindividuals who illustratethe di- manythings, each differentfrom the other. verse backgrounds,abilities,