Vermeer's Masterpiece “The Milkmaid”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vermeer in the Age of the Digital Reproduction and Virtual

VERMEER IN THE AGE OF THE DIGITAL REPRODUCTION AND VIRTUAL COMMUNICATION MIRIAM DE PAIVA VIEIRA Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais ABSTRACT: The twentieth century was responsible for the revival of the visual arts, lending techniques to literature, in particular, after the advent of cinema. This visual revival is illustrated by the intersemiotic translations of Girl with a Pearl Earring: a recent low-budget movie was responsible for the revival of ordinary public interest in an art masterpiece from the seventeenth century. However, it was the book about the portrait that catalyzed this process of rejuvenation by verbalizing the portrait and inspiring the cinematographic adaptation, thereby creating the intersemiotic web. In this media-saturated environment we now live in, not only do books inspire movie adaptations, but movies inspire literary works; adaptations of screenplays are published; movies are adapted into musicals, television shows and even videogames. For James Naremore, every form of retelling should be added to the “study of adaptation in the age of the mechanical reproduction and electronic communication” (NAREMORE, 2000: 12-15), long previewed in Walter Benjamin’s milestone article (1936). Nowadays, the celebrated expression could be changed to the age of the digital reproduction and virtual communication, since new technologies and the use of new media have been changing the relations between, and within, the arts. The objective of this essay is to explore Vermeer’s influence on contemporary art and media production, with focus on the collection of portraits from the book entitled Domestic Landscapes (2007) by the Dutch photographer Bert Teunissen, confirming the study of recycling within a general theory of repetition proposed by James Naremore, under the light of intermediality. -

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

Some Pages from the Book

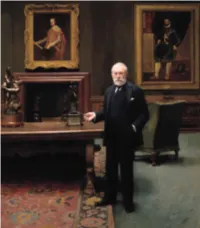

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

The National Gallery Immunity from Seizure

THE NATIONAL GALLERY IMMUNITY FROM SEIZURE Nicolaes Maes: Dutch Master of the Golden Age 22 February 2020 – 30 June 2020 (Extension dates to be confirmed) The National Gallery, London, Trafalgar Square, London, WC2N 5DN Immunity from Seizure IMMUNITY FROM SEIZURE Nicolaes Maes: Dutch Master of the Golden Age 22 February 2020 – 30 June 2020 (Extension dates to be confirmed) The National Gallery, London, Trafalgar Square, London, WC2N 5DN The National Gallery is able to provide immunity from seizure under part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007. This Act provides protection from seizure for cultural objects from abroad on loan to temporary exhibitions in approved museums and galleries in the UK. The conditions are: The object is usually kept outside the UK It is not owned by a person resident in the UK Its import does not contravene any import regulations It is brought to the UK for public display in a temporary exhibition at a museum or gallery The borrowing museum or gallery is approved under the Act The borrowing museum has published information about the object For further enquiries, please contact [email protected] Protection under the Act is sought for the objects listed in this document, which are intended to form part of the forthcoming exhibition, Nicolaes Maes: Dutch Master of the Golden Age. Copyright Notice: no images from these pages should be reproduced without permission. Immunity from Seizure Nicolaes Maes: Dutch Master of the Golden Age 22 February 2020 – 30 June 2020 (Extension dates to be confirmed) Protection under the Act is sought for the objects listed below: Nicolaes Maes (1634 - 1693) © Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada / Photo: Bernard Clark X10056 Abraham's Sacrifice about 1653-54 Place of manufacture: Netherlands Oil on canvas Object dimensions: 113 × 91.5 cm Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada. -

Masterpieces of Dutch Painting from the Mauritshuis October 22, 2013, Through January 19, 2014

Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Hals: Masterpieces of Dutch Painting from the Mauritshuis October 22, 2013, through January 19, 2014 The Frick Collection, New York PRESS IMAGE LIST Digital images are available for publicity purposes; please contact the Press Office at 212.547.6844 or [email protected]. 1. Frans Hals (1581/1585–1666) Portrait of Jacob Olycan (1596–1638), 1625 Oil on canvas 124.8 x 97.5 cm Mauritshuis, The Hague 2. Frans Hals (1581/1585–1666) Portrait of Aletta Hanemans (1606–1653), 1625 Oil on canvas 123.8 x 98.3 cm Mauritshuis, The Hague 3. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) Simeon’s Song of Praise, 1631 Oil on panel (rounded at the upper corners) 60.9 x 47.9 cm Mauritshuis, The Hague 4. Pieter Claesz Vanitas Still Life, 1630 Oil on panel 39.5 x 56 cm Mauritshuis, The Hague 5. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) “Tronie” of a Man with a Feathered Beret, c. 1635 Oil on panel 62.5 x 47 cm Mauritshuis, The Hague 6. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) Susanna, 1636 Oil on panel 47.4 x 38.6 cm Mauritshuis, The Hague 7. Nicolaes Maes The Old Lacemaker, c. 1655 Oil on panel 37.5 x 35 cm Mauritshuis, The Hague 8. Carel Fabritius (1622–1654) The Goldfinch, 1654 Oil on panel 33.5 x 22.8 cm Mauritshuis, The Hague 9. Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681) Woman Writing a Letter, c. 1655 Oil on panel 39 x 29.5 cm Mauritshuis, The Hague 10. Jan Steen (1626–1679) Girl Eating Oysters, c. -

The Engagement of Carel Fabritius's Goldfinch of 1654 with the Dutch

Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art Volume 8, Issue 1 (Winter 2016) The Engagement of Carel Fabritius’s Goldfinch of 1654 with the Dutch Window, a Significant Site of Neighborhood Social Exchange Linda Stone-Ferrier [email protected] Recommended Citation: Linda Stone-Ferrier, “The Engagement of Carel Fabritius’ Goldfinch of 1654 with the Dutch Window, a Significant Site of Neighborhood Social Exchange,” JHNA 8:1 (Winter 2016), DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2016.8.1.5 Available at http://www.jhna.org/index.php/vol-8-1-2016/325-stone-ferrier Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: http://www.hnanews.org/ Terms of Use: http://www.jhna.org/index.php/terms-of-use Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 THE ENGAGEMENT OF CAREL FABRITIUS’S GOLDFINCH OF 1654 WITH THE DUTCH WINDOW, A SIGNIFICANT SITE OF NEIGHBORHOOD SOCIAL EXCHANGE Linda Stone-Ferrier This article posits that Carel Fabritius’s illusionistic painting The Goldfinch, 1654, cleverly traded on the experience of a passerby standing on an actual neighborhood street before a household window. In daily discourse, the window func- tioned as a significant site of neighborhood social exchange and social control, which official neighborhood regulations mandated. I suggest that Fabritius’s panel engaged the window’s prominent role in two possible ways. First, the trompe l’oeil painting may have been affixed to the inner jamb of an actual street-side window, where goldfinches frequently perched in both paintings and in contemporary households. -

Bobbins, Pillows and People

Early Bobbins, Pillows and the People that used them Visual evidence I know of three sixteenth century pictures of lacemakers, one from very early in the seventeenth century and six paintings from the second half of the century. The earliest image is the frontispiece of Nüw Modelbuch.1 This shows two lacemakers working on bulky rectangular pillows resting on high stands. The size and shape of the pillows suggests they are probably filled with tightly packed straw, hay or similar. The bobbins are long, with little in the way of shaping and appear to be quite heavy. Six bobbins are visible on the nearer pillow and at least ten threads, the most that could be shown easily as separate lines. The lace is not shown in any detail, however it is almost certainly one of the patterns from the book, and position of pins indicates that it is being worked 'freehand' ie with pins only along the edge. The lace appears to be worked over a strip of dark fabric which would have helped maintain straight edges. The other pillow, shown from the back, has a small bag holding completed lace, no other detail of lace or bobbins can be seen. In many ways this is a very modern image, showing two women in a working environment, sitting where they can make best use of light from good size windows. It is likely that the amount of space in the room has been exaggerated, but there is a degree of realism that encourages the viewer to Frontispiece of the Nüw Modelbuch, 1561 believe these were real people making real lace. -

Handbook of the Benjamin Altman

HAN DBOO K OF THE B ENJ A M I N A LTM AN COLL ECT I ON I OL D WO MAN CUTT I N G H E R NA I LS By Remb randt T H E M E T R O P O L I T A N M U S E U M l‘ O F A R T HANDBOOK OF BENJAMIN ALTM COLLECTION N EW Y O R K N O V E M B E R M C M ' I V Tabl e of Conte nts PA G E LIST OF I LLUSTRATION S I NTRODUCTION HAN D BOO K GALLERY ON E Dutcb P a intings GALLERY Tw o P a intings of Va r i o us ’ Go l dsmitbs Wo rk Enamel s Crysta l s GALLERI ES TH REE AN D FOUR Chinese P o rce l a i ns Snufi Bo ttl es Lacquers GALLERY FIVE Scripture Rugs Tap estr i e s Fu rn iture Misce l l aneo us Objects 891 List of Il l ustrations Ol d Woman Cut t ing her Nail s By Rembrandt The Lady wi t h a Pink By Rembrandt The Man wi t h a Magnifying-Glass By Rembrandt An Ol d Woman i n an Arm-Chai r By Rembrandt Toilet o f Bathsheba after the Bath By R embrandt Young Gi rl Peeling an Apple By Nicol aes M aes The Merry Company By Frans Hal s Yonke r Ramp and his Sweet hea rt By Frans Hal s Philip I V o f Spain By Diego Vel a zque z Luca s van Uff el By A nthony Van Dyck Portrait o f a Man By Giorgione M argaret Wyatt , Lady Lee By Hans Hol be in the Yo unger v iii L I S T O F I L L U S T R A T I O N S Th e Holy Family By A ndrea M a ntegna The Last Communion of Saint J e rome By Bo tt icel l i ’ Borso d Est e By Cosimo Tura Portrait of a Man By Dirk Bou ts The Betrothal o f Sai nt Catheri ne By Hans M e ml i ng Portrait o f an Ol d Man By Hans Meml ing Triptych M l anese l ate teenth centur i , fif y o f d Cup gol and enamel , called the Ros pigl io si Coupe By Benvenuto Cel l ini Triptych o f Limoges Enamel By Na rdon P enicaud Candlesticks o f Rock Crystal and Silver Gilt German sixtee nth ce ntur , y Ta zz a o f Rock Crystal and E nameled Gold Ital ian s xtee nth centur , i y Portable Holy Water Stoup Ital an s xtee nth ce ntur i , i y Ewer of Smoke Color Rock Crystal German s xtee nth centur , i y Rose Water Vase o f Rock Crystal Ital an s xteenth ce ntur i , i y L I S T O F I L L U S T R A T I O N S ix FAC ING PAG E — Cylindrical Vase of Garniture No s . -

Vermeer As Aporia: Indeterminacy, Divergent Narratives, and Ways of Seeing

Munn Scholars Awards Undergraduate Research 2020 Vermeer as Aporia: Indeterminacy, Divergent Narratives, and Ways of Seeing Iain MacKay Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/munn Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Vermeer as Aporia: Indeterminacy, Divergent Narratives, and Ways of Seeing Iain MacKay Senior Thesis Written in partial fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts in Art History April 23, 2020 Copyright 2020, Iain MacKay ABSTRACT Vermeer as Aporia: Indeterminacy, Divergent Narratives, and Ways of Seeing Iain MacKay Although Johannes Vermeer’s paintings have long been labelled “ambiguous” in the canon of Western Art History, this research aims to challenge the notion of ambiguity. By shifting the conception of Vermeer’s works from ambiguity to indeterminacy, divergent narratives emerge which inform a more complex understanding of Vermeer’s oeuvre. These divergent narratives understand Vermeer’s paintings as turning points in stories that extend beyond the canvas; moments where the possibilities of a situation diverge in different directions. Thus, a myriad of narratives might be contained in a single painting, all of which simultaneously have the possibility of existing, but not the actuality. This interpretation of Vermeer takes evidence from seventeenth-century ways of seeing and the iconographic messages suggested by the paintings within paintings that occur across Vermeer’s oeuvre. Here for the first time, an aporetic approach is utilized to explore how contradictions and paradoxes within a system serve to contribute to holistic meaning. By analyzing four of Vermeer’s paintings – The Concert, Woman Holding a Balance, The Music Lesson, and Lady Seated at a Virginal – through an aporetic lens, an alternative to ambiguity can be constructed using indeterminacy and divergent narratives that help explain compositional and iconographical choices. -

Mannerism and Baroque Art Questions

Mannerism and Baroque Art Questions Go to the AP European History part of the website (http://mrdivis.yolasite.com/). On the left-hand side under “Age of Religious Warfare,” click on “Mannerism and Baroque Art PPT”. This is a slideshow of some of the most well-known artists and paintings from both the Mannerism and Baroque artistic eras. To answer the follow questions, scroll through the slides. 1. In El Greco’s Christ Driving the Traders from the Temple, how is this religious scene depicted different than in the Renaissance? 2. In your own words, how did Mannerism generally differ from Italian Renaissance art? 3. List the Baroque artists covered in the slideshow below: 4. Why was there not an overwhelming number of landscape paintings during the Baroque period? 5. Describe the work of Peter Paul Rubens in general. 6. Describe Rubens’ Glory of St. Ignatius of Loyola. How is St. Ignatius depicted? What is happening in the painting? 7. What does Rubens’ Glory of St. Ignatius of Loyola say about Rubens’ religious views and that of Baroque art in general? Explain. 8. What is symbolic about the subject and content of Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lecture of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp? Explain. 9. In your opinion, why is Rembrandt’s Night Watch considered not just Rembrandt’s masterpiece, but also a symbol of the height of the Dutch Golden Age in the 17th century? 10. Explain what is unique about Jan Vermeer’s work. 11. How does Jan Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring compare to da Vinci’s Mona Lisa? 12. -

Meet the Masters Johannes Vermeer

Meet The Masters Johannes Vermeer • October 1632 --- December 1675 • Dutch painter who lived and worked in Delft • Created some of the most exquisite paintings in Western art. • His works are rare. • He is known to have done only 35 or 36 paintings • Most portray figures inside. • All show light and color The Netherlands Delft China Family History • He began his career in the arts when his father died and Vermeer inherited the family art dealing business. • He continued to work as an art dealer even after he had become a respected painter because he needed the money. Married • Vermeer married a Catholic woman named Catharina Bolnes, even though he was a Protestant. • Catholics in Delft lived in a separate neighborhood than the Protestants and the members of the two religions did not usually spend much time together A Big Family! • Vermeer and his wife had 14 children but not nearly enough money to support them all. Catharina’s mother gave them some money and let the family live with her but Vermeer still had to borrow money to feed his children Patron • Patron: someone who supports the arts • Pieter van Ruijven, one of the richest men in town, became Vermeer’s patron. • He bought many of Vermeer’s paintings and made sure he had canvas, paints, and brushes so he could work. • Having a patron meant that Vermeer could use the color blue in his paintings, a very expensive color in the 1600s because it was made out of the semi-precious stone, lapis lazuli. Not Famous Until Later • After his death Vermeer was overlooked by all art collectors and art historians for more than 200 years. -

Artists' Perception of the Use of Digital Media in Painting

Artists' Perception of the Use of Digital Media in Painting A dissertation presented to the faculty of The Patton College of Education of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Cynthia A. Agyeman December 2015 © 2015 Cynthia A. Agyeman. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Artists' Perception of the Use of Digital Media in Painting by CYNTHIA A. AGYEMAN has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and The Patton College of Education by Teresa Franklin Professor of Educational Studies Renée A. Middleton Dean, The Patton College of Education 3 Abstract AGYEMAN, CYNTHIA A., Ph.D., December 2015, Curriculum and Instruction, Instructional Technology Artists' Perception of the Use of Digital Media in Painting (pp. 310) Director of Dissertation: Teresa Franklin Painting is believed to predate recorded history and has been in existence for over 35,000 (Ayres, 1985; Bolton, 2013) years. Over the years, painting has evolved; new styles have been developed and digital media have been explored. Each period of change goes through a period of rejection before it is accepted. In the 1960s, digital media was introduced to the art form. Like all the painting mediums, it was rejected. It has been over 50 years since it was introduced and yet, it has not been fully accepted as an art form (King, 2002; Miller, 2007; Noll, 1994). This exploratory study seeks to understand the artist’s perception on the use of digital media as an art tool and its benefit to the artists and art education. Grounded theory was used as a methodological guide for the study.