NOTES on SESSION 3: Practice-Led Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Values in Heritage Management

Values in Heritage Management Values in Heritage Management Emerging Approaches and Research Directions Edited by Erica Avrami, Susan Macdonald, Randall Mason, and David Myers THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE, LOS ANGELES The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, John E. and Louise Bryson Director Jeanne Marie Teutonico, Associate Director, Programs The Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) works internationally to advance conservation practice in the visual arts—broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, field projects, and the dissemination of information. In all its endeavors, the GCI creates and delivers knowledge that contributes to the conservation of the world’s cultural heritage. © 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Values in heritage management (2017 : Getty Conservation Institute), author. | Avrami, Erica C., editor. | Getty Conservation Institute, The text of this work is licensed under a Creative issuing body, host institution, organizer. Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- Title: Values in heritage management : emerging NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a approaches and research directions / edited by copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons Erica Avrami, Susan Macdonald, Randall .org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. All images are Mason, and David Myers. reproduced with the permission of the rights Description: Los Angeles, California : The Getty holders acknowledged in captions and are Conservation Institute, [2019] | Includes expressly excluded from the CC BY-NC-ND license bibliographical references. covering the rest of this publication. These images Identifiers: LCCN 2019011992 (print) | LCCN may not be reproduced, copied, transmitted, or 2019013650 (ebook) | ISBN 9781606066201 manipulated without consent from the owners, (epub) | ISBN 9781606066188 (pbk.) who reserve all rights. -

Heritage at Risk

H @ R 2008 –2010 ICOMOS W ICOMOS HERITAGE O RLD RLD AT RISK R EP O RT 2008RT –2010 –2010 HER ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 I TAGE AT AT TAGE ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER Ris K INTERNATIONAL COUNciL ON MONUMENTS AND SiTES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SiTES CONSEJO INTERNAciONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SiTIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст HERITAGE AT RISK Patrimoine en Péril / Patrimonio en Peligro ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER ICOMOS rapport mondial 2008–2010 sur des monuments et des sites en péril ICOMOS informe mundial 2008–2010 sobre monumentos y sitios en peligro edited by Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer Published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin Heritage at Risk edited by ICOMOS PRESIDENT: Gustavo Araoz SECRETARY GENERAL: Bénédicte Selfslagh TREASURER GENERAL: Philippe La Hausse de Lalouvière VICE PRESIDENTS: Kristal Buckley, Alfredo Conti, Guo Zhan Andrew Hall, Wilfried Lipp OFFICE: International Secretariat of ICOMOS 49 –51 rue de la Fédération, 75015 Paris – France Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Cultural Affairs and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag EDITORIAL WORK: Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet, John Ziesemer The texts provided for this publication reflect the independent view of each committee and /or the different authors. Photo credits can be found in the captions, otherwise the pictures were provided by the various committees, authors or individual members of ICOMOS. Front and Back Covers: Cambodia, Temple of Preah Vihear (photo: Michael Petzet) Inside Front Cover: Pakistan, Upper Indus Valley, Buddha under the Tree of Enlightenment, Rock Art at Risk (photo: Harald Hauptmann) Inside Back Cover: Georgia, Tower house in Revaz Khojelani ( photo: Christoph Machat) © 2010 ICOMOS – published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3 CONTENTS Foreword by Francesco Bandarin, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, Paris .................................. -

Or the Archaeology of Nothing)

An Archaeology of absence (or the archaeology of nothing) Tim Owen 70 THE FUTURE FOR HERITAGE PRACTICE Abstract Through the context of contemporary archaeological practice in South Western Sydney, this paper explores themes of Australian Aboriginal archaeological interpretation, presenting two complementary frameworks for interpretation: the ‘three-tiered framework’ and the ‘archaeology of absence’. Examining the outcomes from a recent Aboriginal archaeological excavation at East Leppington, South Western Sydney, intra and inter site archaeological patterning resulting from long-term Aboriginal habitation, has been identified. The interpretation of the data has been undertaken on the premise that stratigraphically intact archaeological deposits are possibly the consequence of long-term practice of Aboriginal tradition and perhaps law. The interpretations are presented through the three-tiered framework. To build further understanding of Aboriginal landscape use, this paper questions whether locations with ‘nothing’ should be considered important to an understanding of the whole. It is suggested that the context of empty space can be as important within a cultural landscapes as those locations where archaeological evidence abounds. Nothingness is not a state of absence of objects but rather affirms the existence of the unseen behind the empty space. (Davis and Ikeno 2002: 255). Australian heritage context has been provided by considering the two frameworks applicability through the Burra Charter 2013, and the Burra Charter Indigenous Practice Note. Introduction Archaeological investigation of a site or place may yield evidence, the creation of which was governed by Aboriginal law, tradition and power. Stratigraphically and/or spatially intact archaeological evidence may suggest long-term patterns of human occupation and behaviour – locations that were repeatedly used for specific purposes on each visit to a place. -

Innovation in Conservation

Innovation in conservation A timeline history of Australia ICOMOS and the Burra Charter Bronwyn Hanna Report commissioned by Australia ICOMOS Sydney, 2015 (amended 2017) This is an unpublished report commissioned by Australia ICOMOS Inc. Copyright: Bronwyn Hanna (and others where indicated) The Burra Charter advocates a cautious approach to change: do as much as necessary to care for the place and to make it useable, but otherwise change it as little as possible so that its cultural significance is retained. (Burra Charter, preamble, 2013) We are all grateful for Australia ICOMOS’s contributions for the benefit of our collective cultural heritage. Of course you gave us the Burra Charter, but you continue to give us so much more. (Gunny Harboe, US ICOMO, excerpt from an email message of congratulations to Sheridan Burke and Kristal Buckley upon receiving their honorary memberships of ICOMOS, 14 February 2015) Image, front cover: Australia ICOMOS members inspecting mining heritage at Burra, South Australia on the day the Burra Charter was first endorsed by Australia ICOMOS, 19 August 1979. Photo by Richard Allom ©, courtesy Peter Marquis-Kyle. Bronwyn Hanna: A timeline history of Australia ICOMOS, 2017 2 Contents Preface— Issues for exploration in a history of Australia ICOMOS—Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations 7 Key personnel 8 Introduction—What is Australia ICOMOS? 10 Australia ICOMOS Timeline (1877-2015) 14 Annexures 1. List of oral history interviews undertaken by Bronwyn Hanna for the National Library of Australia 65 2012-2014 2. List of oral history interviews undertaken by Jennifer Cornwall and others for the Paul Ashton and 66 Jennifer Cornwall Australian Heritage Commission History Project in 2002 3. -

The Places We Keep: the Heritage Studies of Victoria and Outcomes for Urban Planners

The places we keep: the heritage studies of Victoria and outcomes for urban planners Robyn Joy Clinch Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Architecture & Planning) June 2012 Faculty of Architecture, Building & Planning The University of Melbourne Abstract The incentive for this thesis that resulted from an investigation into the history of my heritage house, developed from my professional interest in the planning controls on heritage places. This was further motivated by my desire to reinvent my career as an urban planner and to use my professional experience in management, marketing and information technology. As a result, the aim of this thesis was to investigate the relationship between the development of the heritage studies of Victoria and the outcome of those documents on planning decisions made by urban planners. The methods used included a simulated experience that established a methodology for the thesis. In addition, interviews were conducted with experts in the field that provided a context for understanding the influencing factors of when, where, by whom, with what, why and how the studies were conducted. These interviews also contributed to the understanding of how the historical research had been undertaken and used to establish the significance of places and how this translated into outcomes for urban planners. Case studies in the form of Tribunal determinations have been used to illustrate key outcomes for urban planners. A large amount of information including that relating to the historical background of the studies plus a collection of indicative content from over 400 heritage studies was traversed. -

World Heritage Cultural Landscapes 2011

Prepared and edited by UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre. Updated by Francesca Giliberto and Lucile Smirnov. UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre. Préparé et édité par le Centre de Documentation UNESCO-ICOMOS. Actualisé par Francesca Giliberto et Lucile Smirnov. © UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre, September 2011. ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and sites / Conseil International des Monuments et des Sites 49-51 rue de la Fédération 75015 Paris FRANCE http://www.international.icomos.org UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre / Centre de Documentation UNESCO-ICOMOS : http://www.international.icomos.org/centre_documentation/index.html Cover photographs: Photos de couverture : Cinque Terre, Italy: © OUR PLACE The World Heritage Collection / OUR PLACE The World Heritage Collection; St Kilda, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: © Nomination File / Nomination File | Image Source: Nomination File; Viñales Valley, Cuba: © UNESCO / Ron Van Oers | Image Source: WHC Content / Sommaire Introduction To Cultural Landscapes ..................................................................................................................... 5 Definition ......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 History And Terminology ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Categories ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

7Th Conservation Plan

THE SEVENTH EDITION CONSERVATION PLAN JAMES SEMPLE KERR AUSTRALIA ICOMOS THE SEVENTH EDITION CONSERVATION PLAN A GUIDE TO THE PREPARATION OF CONSERVATION PLANS FOR PLACES OF EUROPEAN CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE JAMES SEMPLE KERR 2013 – ii – Acknowledgments The guide was first prepared for seminars sponsored in 1981 by the Historic Houses Trust of NSW, the Australian Heritage Commission and the Commonwealth Department of Housing and Construction. The various editions evolved with the help of comments from the people listed below. Richard Allom George Farrant Richard Mackay Andrew Andersons Don Godden Eric Martin Rosemary Annable Bronwyn Hanna Richard Morrison Max Bourke Dinah Holman Michael Pearson Graham Brooks Peter James Juliet Ramsay Sheridan Burke Richard Johnson Sharon Sullivan Lorraine Cairns Chris Johnston Wendy Thorp Ken Charlton Joan Kerr Meredith Walker Kate Clark Tamsin Kerr Anne Warr Alan Croker Miles Lewis Peter Watts Geoff Dawson Susan Macdonald Dennis Watkins Joan Domicelj Barry McGregor Greg Young Photographs other than those taken by the author were reproduced by permission of National Library of Australia (fig.9 on page 9, and fig.20 on page 53), John Fairfax and Sons (fig.10 on page 12) and the Museum of Applied Arts and Science (fig.23 on page 52). Cover photograph: Mr Solomon Wiseman’s house ‘Cobham’ at Wiseman’s Ferry about 1830, artist unknown. National Trust of Australia (NSW) collection. Originally published by J.S. Kerr on behalf of The National Trust of Australia (NSW) and available from the Trust at Observatory Hill, Sydney, NSW 2000. This version placed on the Australia ICOMOS Inc. website with the agreement of James Semple Kerr. -

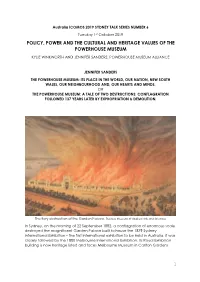

PMA Australia ICOMOS JS

Australia ICOMOS 2019 SYDNEY TALK SERIES NUMBER 6 Tuesday 1st October 2019 POLICY, POWER AND THE CULTURAL AND HERITAGE VALUES OF THE POWERHOUSE MUSEUM KYLIE WINKWORTH AND JENNIFER SANDERS, POWERHOUSE MUSEUM ALLIANCE JENNIFER SANDERS THE POWERHOUSE MUSEUM: ITS PLACE IN THE WORLD, OUR NATION, NEW SOUTH WALES, OUR NEIGHBOURHOOD AND, OUR HEARTS AND MINDS. OR THE POWERHOUSE MUSEUM: A TALE OF TWO DESTRUCTIONS: CONFLAGRATION FOLLOWED 137 YEARS LATER BY EXPROPRIATION & DEMOLITION. The fiery destruction of the Garden Palace. Trustees Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences In Sydney, on the morning of 22 September 1882, a conflagration of enormous scale destroyed the magnificent Garden Palace built to house the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition – the first international exhibition to be held in Australia. It was closely followed by the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition. Its Royal Exhibition building is now heritage listed and faces Melbourne Museum in Carlton Gardens. 1 The Garden Palace built for the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition, Royal Botanic Gardens, photograph by Charles Bayliss, 1850-1897. The imposing brick and wooden structure, crowned by the largest dome in the southern hemisphere, was designed by Colonial Architect James Barnet, and constructed in just 8 months, aided by the first practical use of electric light in Australia. The Crystal Palace built to house London’s 1851 Great Exhibition 2 Sydney’s 1879 Exhibition was inspired by the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations which opened in London’s Crystal Palace in May 1851. This was a period of incredible optimism and capacity when Australia took its place in the nations of the world, embracing new technologies and creating new collections for new cultural institutions. -

'The Waters of Australian Deserts' Cultural Heritage Study

‘The Waters of Australian Deserts’ Cultural Heritage Study A report to the Department of Environment and Energy and the Australian Heritage Council Canning Stock Route and surrounding country 2008, by 14 women artists at Kunawarritji (well 33 of the Canning Stock Route). Showing waterholes made into wells in the country crossed by the Canning Stock Route, and alternative permanent and ephemeral water places used when the Canning wells were closed off to the Martu people (Yiwarra Kuju 2010: 44-5) Ingereth Macfarlane and Anne McConnell Final Report March 2017 1 Table of contents List of tables ............................................................................................................................. 3 List of maps and figures............................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... 5 PART 1: Introduction and background ........................................................................................ 6 1.1 Introduction to the study ............................................................................................... 6 1.2 The study area ............................................................................................................... 7 1.3 Study scope................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Existing cultural heritage identification