7Th Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trial Bay Gaol Conservation Management Plan

2.0 Trial Bay Gaol: the Site and its History 2.1 Location and Site Description Trial Bay Gaol occupies a landmark position on the tip of Laggers Point at Arakoon. The gaol has extensive views in most directions and it is also clearly visible from a range of vantage points including South West Rocks. The site is approximately 500km north of Sydney and south of Brisbane, mid-way between Port Macquarie and Coffs Harbour. The closest large town is Kempsey, inland on the Macleay River. The site is at the southern edge of Trial Bay. While Arakoon is the local village, South West Rocks is the main town of the area. The Arakoon Conservation Area forms the northern edge of a series of national parks and conservation areas the largest of which is Hat Head National Park. Trial Bay Gaol is one of a series of historic sites in the locality, the other major site being Smoky Cape Lighthouse Group. The gaol was constructed on a granite outcrop as close to the point as possible with the intent of placing the workforce for the breakwater construction immediately adjacent to the worksite. The proximity can be seen by the quarry excavation almost abutting the northern edge of the gaol wall, requiring stabilising of the rockface in recent years. The gaol was also carefully located with a mind to security and the narrow headland proved a relatively easy site to guard. Early photographs and plans show the gaol site with its demarcation and protective lines set within a cleared landscape to assist in guarding the perimeter. -

Harbour Bridge to South Head and Clovelly

To NEWCASTLE BARRENJOEY A Harbour and Coastal Walk Personal Care This magnificent walk follows the south-east shoreline of Sydney Harbour The walk requires average fitness. Take care as it includes a variety of before turning southwards along ocean beaches and cliffs. It is part of one pathway conditions and terrain including hills and steps. Use sunscreen, of the great urban coast walks of the world, connecting Broken Bay in carry water and wear a hat and good walking shoes. Please observe official SYDNEY HARBOUR Sydney's north to Port Hacking to its south (see Trunk Route diagram), safety and track signs at all times. traversing the rugged headlands and sweeping beaches, bush, lagoons, bays, and harbours of coastal Sydney. Public Transport The walk covered in this map begins at the Circular Quay connection with Public transport is readily available at regular points along the way Harbour Bridge the Harbour Circle Walk and runs to just past coastal Bronte where it joins (see map). This allows considerable flexibility in entering and exiting the Approximate Walking Times in Hours and Minutes another of the series of maps covering this great coastal and harbour route. routes. Note - not all services operate every day. to South Head e.g. 1 hour 45 minutes = 1hr 45 The main 29 km Harbour Bridge (B3) to South Head (H1) and to Clovelly Bus, train and ferry timetables. G8) walk (marked in red on the map) is mostly easy but fascinating walk- Infoline Tel: 131-500 www.131500.com.au 0 8 ing. Cutting a 7km diagonal across the route between Rushcutters Bay (C5) and Clovelly kilometres and Clovelly, is part of the Federation Track (also marked in red) which, in Short Walks using Public Transport Brochure 1 To Manly NARRABEEN full, runs from Queensland to South Australia. -

Talking Tablelands with Adam Marshall MP Your Member for Northern Tablelands

May 2016 Talking Tablelands with Adam Marshall MP your Member for Northern Tablelands Year off to a good start THE past few months have been incredibly busy and very fruitful in regard to some wonderful funding which has come our region’s way for infrastructure upgrades and support for Work underway on $60 million community organisations. In January I had the pleasure of meeting members from Armidale Hospital redevelopment 22 community organisations across the Northern Tablelands successful in gaining $300,000 through the Community Building Partnership. It’s one of the highlights of my role to be able to – Main construction on track to start July this year help facilitate these grants and a pleasure to talk to the people who are so passionate about improving outcomes for their local communities. I WAS delighted to visit the work site at the central sterilising supplies department and a new I recently took the Roads Minister Duncan Gay on a tour of Armidale Rural Referral Hospital where several and expanded critical care unit. the region to press the case for some major road works that, if buildings have been demolished to make way for Pleasingly, 6,000 of the Armidale blue bricks implemented, will give a huge boost to the local economy. a new four-storey structure, as part of the $60 from the former infectious diseases ward I’m continuing to knock on the Regional Development Minister’s million redevelopment building have been preserved and will be used door to garner support for the additional $6.3 million Armidale It’s a wonderful milestone for the Armidale in the construction of the new building – a Dumaresq Council needs to upgrade the regional airport and road community and one which has been long- wonderful way to blend the old with the new at links. -

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey 43-51 Cowper Wharf Road September 2013 Woolloomooloo NSW 2011 w: www.mgnsw.org.au t: 61 2 9358 1760 Introduction • This report is presented in two parts: The 2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and the 2013 NSW Small to Medium Museum & Gallery Survey. • The data for both studies was collected in the period February to May 2013. • This report presents the first comprehensive survey of the small to medium museum & gallery sector undertaken by Museums & Galleries NSW since 2008 • It is also the first comprehensive census of the museum & gallery sector undertaken since 1999. Images used by permission. Cover images L to R Glasshouse, Port Macquarie; Eden Killer Whale Museum , Eden; Australian Fossil and Mineral Museum, Bathurst; Lighting Ridge Museum Lightning Ridge; Hawkesbury Gallery, Windsor; Newcastle Museum , Newcastle; Bathurst Regional Gallery, Bathurst; Campbelltown arts Centre, Campbelltown, Armidale Aboriginal Keeping place and Cultural Centre, Armidale; Australian Centre for Photography, Paddington; Australian Country Music Hall of Fame, Tamworth; Powerhouse Museum, Tamworth 2 Table of contents Background 5 Objectives 6 Methodology 7 Definitions 9 2013 Museums and Gallery Sector Census Background 13 Results 15 Catergorisation by Practice 17 2013 Small to Medium Museums & Gallery Sector Survey Executive Summary 21 Results 27 Conclusions 75 Appendices 81 3 Acknowledgements Museums & Galleries NSW (M&G NSW) would like to acknowledge and thank: • The organisations and individuals -

Sydney Gateway

Sydney Gateway State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report BLANK PAGE Sydney Gateway road project State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report Roads and Maritime Services | November 2018 Prepared by the Gateway to Sydney Joint Venture (WSP Australia Pty Limited and GHD Pty Ltd) and Roads and Maritime Services Copyright: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of NSW Roads and Maritime Services. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of NSW Roads and Maritime Services constitutes an infringement of copyright. Document controls Approval and authorisation Title Sydney Gateway road project State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report Accepted on behalf of NSW Fraser Leishman, Roads and Maritime Services Project Director, Sydney Gateway by: Signed: Dated: 16-11-18 Executive summary Overview Sydney Gateway is part of a NSW and Australian Government initiative to improve road and freight rail transport through the important economic gateways of Sydney Airport and Port Botany. Sydney Gateway is comprised of two projects: · Sydney Gateway road project (the project) · Port Botany Rail Duplication – to duplicate a three kilometre section of the Port Botany freight rail line. NSW Roads and Maritime Services (Roads and Maritime) and Sydney Airport Corporation Limited propose to build the Sydney Gateway road project, to provide new direct high capacity road connections linking the Sydney motorway network with Sydney Kingsford Smith Airport (Sydney Airport). The location of Sydney Gateway, including the project, is shown on Figure 1.1. Roads and Maritime has formed the view that the project is likely to significantly affect the environment. On this basis, the project is declared to be State significant infrastructure under Division 5.2 of the NSW Environmental Planning & Assessment Act 1979 (EP&A Act), and needs approval from the NSW Minister for Planning. -

Heritage Near Me Team: Email: [email protected] Phone +612 9873 8544

Further information: www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritage-near-me To contact the Heritage Near Me team: Email: [email protected] Phone +612 9873 8544 Protect, share & celebrate our local heritage Every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this document is accurate at the time of publication. However, as appropriate, readers should obtain independent advice before making any decision based on this information. Cover photography:Aboriginal rock art, Mutawintji Historic Site. Photo: Office of Environment and Heritage Photography inside brochure (left to right): Trial Bay Gaol, Arakoon (D Finnegan/OEH), Aboriginal scarred canoe tree at Broulee (John Spencer/OEH), Ship wreck of the SS Minmi Cape Banks area Kamay Botany Bay National Park (Andrew Richards/OEH), Flowerdale Lagoon, Wagga Wagga (John Spencer/OEH) Published by Office of Environment and Heritage 59 Goulburn Street, Sydney NSW 2000 PO Box A290, Sydney South NSW 1232 Phone: +61 2 9995 5000 (switchboard) Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 978-1-76039-492-1 October 2016 OEH 2016/0553 Support for local heritage Heritage Near Me is a program from • development opportunities enable communities The Heritage Near Me Incentives program Heritage Management System to promote and activate their local heritage includes three new grant streams: NSW Office of the Environment and The Heritage Management System is a two-year • work in partnership with communities and Heritage (OEH) that helps NSW 1. Heritage Activation Grants: The Heritage technology project that will change the way councils to build sustainable futures for Activation Grants support projects that users’ access heritage information. -

Parramatta Park

• • A HOUSE FULL OF ARTEFACTS OR • ARTEFACTS FOR THE HOUSE ? • papers from a semlnar about the interpretation and presentation of Old Government House, Parramatta • 14 & 15 February, 1985. • • • TH1e National Must of Australia (N SW) • • • ARTEFACTS • o~ • . ~ pa er~. fro~a seminar about the inter et~(}on and presentation of Old Govern~nt House, Parramatta 14 & 15 February, 1985. • • • • rue NationaR Must ofp\U]stnilia (NSW) • • • • • A HOUSE FULL OF ARTEFACTS • OR ARTEFACTS FOR THE HOUSE ? • papers from a seminar about the interpretation and presentation of Old Government House, Parramatta 14 & 15 February, 1985. • • • • The National Trust of Australia (NSW) • • .' • A HOUSE FULL OF ARTEFACTS OR ARTEFACTS FOR THE HOUSE? • papers from a seminar about the interpretation and presentation of Old Government House, Parramatta. CONTENTS. • FOREWORD Richard Rowe? OPENING Pat McDonald • PART 1. OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE TODAY 1.1 BACKGROUND PAPER Meredith Walker • 1.2 CURRENT INTERPRETATION AND PRESENTATION OPERATION AND VISITORS Chris Levins 1.3 CURRENT "INTERPRETATION AND PRESENTATION THE DISPLAY Patricia McDonald • 1.4 HISTORY OF THE DISPLAY Kevin Fahy 1.5 HISTORICAL INTERIORS AND THE FURNITURE Kevin Fahy • 1.6 HISTORICAL INVENTORIES AND ROOM USAGE AT OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE James Broadbent 1.7 BUILDING CONDITIONS AND PROBLEMS Alan Croker • PART 2. THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE AND ITS INTERPRETATION AND PRESENTATION. • 2.1 ON RECONSIDERING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE Helen Proudfoot 2.2 THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE Richard Mackay • 2.3 THE ARCHITECTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE James Broadbent 2.4 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE FURNITURE Kevin Fahy • 2.5 THE HISTORY OF THE GARDEN AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE Joanna Capon • • 2.6 THE FUTURE OF THE PAST IN NEW GOVERNMENT HOUSE, PARRAMATTA: • PRESENTING THE INTERIOR Jessie Serle 2.7 PRESERVING AND PRESENTING THE ARTEFACTS Donna Midwinter • 2.8 DRAFT STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE Ian Stapleton '. -

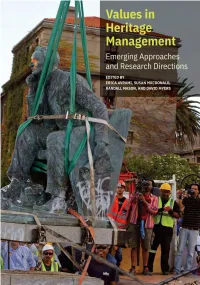

Values in Heritage Management

Values in Heritage Management Values in Heritage Management Emerging Approaches and Research Directions Edited by Erica Avrami, Susan Macdonald, Randall Mason, and David Myers THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE, LOS ANGELES The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, John E. and Louise Bryson Director Jeanne Marie Teutonico, Associate Director, Programs The Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) works internationally to advance conservation practice in the visual arts—broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, field projects, and the dissemination of information. In all its endeavors, the GCI creates and delivers knowledge that contributes to the conservation of the world’s cultural heritage. © 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Values in heritage management (2017 : Getty Conservation Institute), author. | Avrami, Erica C., editor. | Getty Conservation Institute, The text of this work is licensed under a Creative issuing body, host institution, organizer. Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- Title: Values in heritage management : emerging NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a approaches and research directions / edited by copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons Erica Avrami, Susan Macdonald, Randall .org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. All images are Mason, and David Myers. reproduced with the permission of the rights Description: Los Angeles, California : The Getty holders acknowledged in captions and are Conservation Institute, [2019] | Includes expressly excluded from the CC BY-NC-ND license bibliographical references. covering the rest of this publication. These images Identifiers: LCCN 2019011992 (print) | LCCN may not be reproduced, copied, transmitted, or 2019013650 (ebook) | ISBN 9781606066201 manipulated without consent from the owners, (epub) | ISBN 9781606066188 (pbk.) who reserve all rights. -

Lisa Kealhofer

Lisa Kealhofer Anthropology and Environmental Studies and Sciences Departments, Santa Clara University Santa Clara, CA 95053 Ph: 408 554 6810 Fax: 408 554 4189 EDUCATION University of Pennsylvania, Anthropology Department, Philadelphia, PA, 1991 PhD Thesis: Cultural Interaction during the Spanish Colonial Period: El Pueblo de Los Angeles, California Macalester College, St. Paul, MN, 1981 B.A. Anthropology and Chemistry EXPERIENCE Teaching and Administration 2006 -2013 Chair, Department of Anthropology, Santa Clara University 2006 (W&Spr) Acting Director, Environmental Studies Institute 2012- Professor, Santa Clara University, Departments of Anthropology/Environmental Studies and Sciences 2005-2012 Associate Professor, Santa Clara University, Department of Anthropology/Environmental Studies Program 1999-2005 Assistant Professor, Santa Clara University, Department of Anthropology and Sociology/Environmental Studies Program 1994-1999 Visiting Assistant Professor, The College of William and Mary, Anthropology Department 1990 Lecturer, Anthropology, Bryn Mawr College 1989-1990 Lecturer, University of Pennsylvania, College of General Studies Research School for Advanced Research, Seminar participant. The Thailand Archaeometallurgy Project: A Holistic Approach to Characterizing Metallurgy’s Societal Impact in Prehistoric Southeast Asia, April 29 – May 1, 2014. Cotsen Fellow, School for Advanced Research, After the Fall: Iron Age Interaction in Central Anatolia. Summer 2009. Senior Fulbright Specialist, ICAES, Southeast Asia Environment and Phytoliths, -

Australian Silhouettes

from the Collection of the Sydney Living Museums Australian Silhouettes Complied by Lauren Muney, “Silhouettes By Hand” For use at the Lost Trades Fair Kyneton, VIC D'Arcy Wentworth Silhouette of D'Arcy Wentworth (1762-1827) / artist unknown Date: [c1815] 1 framed silhouette painted on glass : bronzed ; 8 x 5.5 cm Handwritten on back: 'Believed to be / Darcy Wentworth / sometime prior to / 1827'. D'Arcy Wentworth (1762-1827), was born near Portadown, Ireland, the sixth of the eight children of D'Arcy Wentworth and his wife, Martha Dickson. He served as an ensign in the First Armagh Company of the Irish Volunteers while also serving an apprenticeship for the medical profession. Later, while living in London, he found himself in financial difficulties and at the Old Bailey sessions beginning on 12 December 1787 he was thrice charged with highway robbery: twice he was found not guilty and in the third acquitted for lack of evidence. At the conclusion of the case the prosecutor informed the judge: 'My Lord, Mr. Wentworth, the prisoner at the Bar, has taken a passage to go in a fleet to Botany Bay and has obtained an appointment in it as Assistant Surgeon and desires to be discharged immediately'. Wentworth arrived at Port Jackson in the transport Neptune on 28 June 1790. On 1 August he sailed in the Surprize for Norfolk Island where he began his Australian career as an assistant in the hospital. He was appointed superintendent of convicts at Norfolk Island from 10 September 1791, returning to Sydney in February 1796 where he was appointed one of the assistant surgeons of the colony and later principal surgeon of the Civil Medical Department. -

Heritage at Risk

H @ R 2008 –2010 ICOMOS W ICOMOS HERITAGE O RLD RLD AT RISK R EP O RT 2008RT –2010 –2010 HER ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 I TAGE AT AT TAGE ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER Ris K INTERNATIONAL COUNciL ON MONUMENTS AND SiTES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SiTES CONSEJO INTERNAciONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SiTIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст HERITAGE AT RISK Patrimoine en Péril / Patrimonio en Peligro ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER ICOMOS rapport mondial 2008–2010 sur des monuments et des sites en péril ICOMOS informe mundial 2008–2010 sobre monumentos y sitios en peligro edited by Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer Published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin Heritage at Risk edited by ICOMOS PRESIDENT: Gustavo Araoz SECRETARY GENERAL: Bénédicte Selfslagh TREASURER GENERAL: Philippe La Hausse de Lalouvière VICE PRESIDENTS: Kristal Buckley, Alfredo Conti, Guo Zhan Andrew Hall, Wilfried Lipp OFFICE: International Secretariat of ICOMOS 49 –51 rue de la Fédération, 75015 Paris – France Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Cultural Affairs and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag EDITORIAL WORK: Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet, John Ziesemer The texts provided for this publication reflect the independent view of each committee and /or the different authors. Photo credits can be found in the captions, otherwise the pictures were provided by the various committees, authors or individual members of ICOMOS. Front and Back Covers: Cambodia, Temple of Preah Vihear (photo: Michael Petzet) Inside Front Cover: Pakistan, Upper Indus Valley, Buddha under the Tree of Enlightenment, Rock Art at Risk (photo: Harald Hauptmann) Inside Back Cover: Georgia, Tower house in Revaz Khojelani ( photo: Christoph Machat) © 2010 ICOMOS – published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3 CONTENTS Foreword by Francesco Bandarin, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, Paris .................................. -

New Voices in Japanese Studies

NEW voices Volume 1: Cross-Cultural Encounters in the Australia-Japan Relationship NEW Voices oices VW NE New Voices: Cross-Cultural Encounters in the Australia–Japan Relationship The Japan Foundation, Sydney i New Voices New Voices Volume 1: Cross-Cultural Encounters in the Australia–Japan Relationship December 2006 © Copyright The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2006 All material in New Voices is copyright. Copyright of each piece belongs to the author. Copyright of the collection belongs to the editors. Apart from any fair use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without the prior permission of the author or editors. The Japan Foundation, Sydney Shop 23, Level 1 Chifley Plaza 2 Chifley Square SYDNEY NSW 2000 Tel. (02) 8239 0055 Fax. (02) 9222 2168 www.jpf.org.au Editorial Advisory Board: Professor KŌichi Iwabuchi, Waseda University Professor Purnendra Jain, Adelaide University Professor Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Australian National University Professor Yoshio Sugimoto, La Trobe University Associate Professor Alison Tokita, Monash University Editor, Volume 1 Dr Yuji Sone, Macquarie University Editors Wakao Koike, Deputy Director, The Japan Foundation, Sydney David Boyd, Program Coordinator, The Japan Foundation, Sydney The views expressed in this journal are those of the authors, and do not necessarily coincide with those of the editors or members of the Editorial Advisory Board. Japanese names are written surname first, except where the person concerned has adopted Anglo-European conventions. The long vowel sound in Japanese is indicated by a macron (e.g. kŌtsū), unless in common use without (e.g. Tokyo). ISSN: 1833-5233 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21159/nv.01 Printed in Australia by Southwood Press Pty Ltd.