What Is the Impact of the Application of the Nonviolent Communication Model on the Development of Empathy? Overview of Research and Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Working with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Related Communication & Social Skill Challenges Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP Speech-Language Pathologist Consultant for Autism Spectrum Disorders [email protected] Learning effective conversation skills ranks as one of the most significant social abilities that students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) need to accomplish. Educators and parents list the challenges: “Steve talks too much.” “Shannon doesn’t take her turn.” “Aiden talks when no one is listening.” “Brandon perseverates on inappropriate topics.” “Kim doesn’t respond when people try to communicate with her.” The list goes on and on. Difficulty with conversation prevents these students from successfully taking part in social opportunities. What makes learning conversation skills so difficult? Conversation requires exactly the skills these students have difficulty with, such as: • Attending • Quickly taking in and processing information • Interpreting confusing social cues • Understanding vocabulary • Comprehending abstract language Many of those skills that create skillful conversation are just the ones that are difficult as a result of the core deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Think about it. From the student’s point of view, conversation can be very puzzling. Conversation is dynamic. .fleeting. .changing. .unpredictable. © Linda Hodgdon, 2007 1 All Rights Reserved This article may not be duplicated, -

Recommended Reading

Recommended Reading: Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life 2nd Ed Create Your Life, Your Relationships and Your World in Harmony with Your Values by Marshall B. Rosenberg, Ph.D. Most of us are hungry for skills to improve the quality of our relationships, to deepen our sense of personal empowerment or to simply communicate more effectively. Unfortunately, for centuries our prevailing culture has taught us to think and speak in ways that can actually perpetuate conflict, internal pain and even violence. Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life partners practical skills with a powerful consciousness and vocabulary to help us get what we want peacefully. In this internationally acclaimed text, Marshall Rosenberg offers insightful stories, anecdotes, practical exercises and role-plays that will literally change your approach to communication for the better. Discover how the language you use can strengthen your relationships, build trust, prevent conflicts and heal pain. Revolutionary, yet simple, Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life offers the most effective tools to reduce violence and create peace by changing how we communicate. Over 250,000 copies have been sold. Printed in over 20 languages around the world. Approximately 250,000 people each year from all walks of life are learning these life-changing communication skills. Speak Peace in a World of Conflict What You Say Next Will Change Your World by Marshall B. Rosenberg, Ph.D. In every interaction, every conversation and in every thought, you have a choice – to promote peace or perpetuate violence. International peacemaker, mediator and healer, Dr. Marshall B. Rosenberg shows you how the language you use is the key to enriching life. -

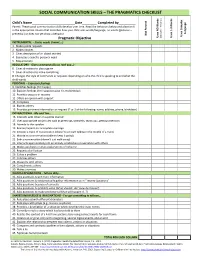

Social Communication Skills – the Pragmatics Checklist

SOCIAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS – THE PRAGMATICS CHECKLIST Child’s Name Date .Completed by . Words Preverbal) Parent: These social communication skills develop over time. Read the behaviors below and place an X - 3 in the appropriate column that describes how your child uses words/language, no words (gestures – - Language preverbal) or does not yet show a behavior. Present Not Uses Complex Uses Complex Gestures Uses Words NO Uses 1 Pragmatic Objective ( INSTRUMENTAL – States needs (I want….) 1. Makes polite requests 2. Makes choices 3. Gives description of an object wanted 4. Expresses a specific personal need 5. Requests help REGULATORY - Gives commands (Do as I tell you…) 6. Gives directions to play a game 7. Gives directions to make something 8. Changes the style of commands or requests depending on who the child is speaking to and what the child wants PERSONAL – Expresses feelings 9. Identifies feelings (I’m happy.) 10. Explains feelings (I’m happy because it’s my birthday) 11. Provides excuses or reasons 12. Offers an opinion with support 13. Complains 14. Blames others 15. Provides pertinent information on request (2 or 3 of the following: name, address, phone, birthdate) INTERACTIONAL - Me and You… 16. Interacts with others in a polite manner 17. Uses appropriate social rules such as greetings, farewells, thank you, getting attention 18. Attends to the speaker 19. Revises/repairs an incomplete message 20. Initiates a topic of conversation (doesn’t just start talking in the middle of a topic) 21. Maintains a conversation (able to keep it going) 22. Ends a conversation (doesn’t just walk away) 23. -

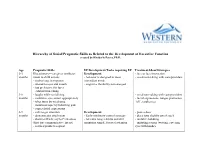

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

A Communication Aid Which Models Conversational Patterns

A communication aid which models conversational patterns. Norman Alm, Alan F. Newell & John L. Arnott. Published in: Proc. of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ‘87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. A communication aid which models conversational patterns Norman ALM*, Alan F. NEWELL and John L. ARNOTT University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, U.K. The research reported here was published in: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ’87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. The RESNA (Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America) site is at: http://www.resna.org/ Abstract: We have developed a prototype communication system that helps non-speakers to perform communication acts competently, rather than concentrating on improving the production efficiency for specific letters, words or phrases. The system, called CHAT, is based on patterns which are found in normal unconstrained dialogue. It contains information about the present conversational move, the next likely move, the person being addressed, and the mood of the interaction. The system can move automatically through a dialogue, or can offer the user a selection of conversational moves on the basis of single keystrokes. The increased communication speed which is thus offered can significantly improve both the flow of the conversation and the disabled person’s control of the dialogue. * Corresponding author: Dr. N. Alm, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, UK. A communication aid which models conversational patterns INTRODUCTION The slow rate of communication of people using communication aids is a crucial problem. -

Attorney Well-Being: Transforming Our Workplaces Towards Better Health & Sustainability

Friday, Nov. 8, 2019 9:15 AM – 10:30 AM Session 101 | Attorney Well-Being: Transforming Our Workplaces Towards Better Health & Sustainability Attorneys face incredible demands and pressures at work that invariably leave little room for comfort, rest, and self-care. This comes at a high cost to our own well-being. Rates of stress, anxiety, substance abuse, depression, and job dissatisfaction are alarmingly high in this profession. Unaddressed, these issues can lead to burnout, illness, and other serious outcomes. What can we do to transform ourselves and our own workplaces towards well-being and sustainability in lawyering? Come hear from a panel of fellow lawyers dedicated to the cause: the co-chair of the ABA’s National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being and chair of the ABA’s Commission on Lawyers Assistance Programs; a published expert on attorney mindfulness and work-life integration; a distinguished in-house counsel whose passions align with attorney well-being across companies; and an experienced attorney with firsthand knowledge of managing law-firm stressors in an attempt to lead a balanced life. Moderating the panel is a former lawyer-turned-career coach dedicated to helping lawyers gain clarity and fulfillment. This is an interactive workshop. Panel and small group discussion topics will include (1) ways of regularly engaging in habits and practices to decrease stress and anxiety; (2) exploring the challenges of prioritizing well-being and how to make time for self-care; (3) causes of attorney burnout and health issues prevalent in the profession; (4) creating a workplace that prioritizes employee wellbeing; (5) how well-being initiatives help to create a more inclusive work environment; and (6) examples of workplace initiatives to improve attorney well-being. -

2 Parts and 4 Components of NVC

2 Parts and 4 Components of NVC empathetically listening: honestly expressing: observations observations feelings feelings needs needs requests requests Both sides of the NVC model: empathetically listening and honestly expressing, use the four steps of the model: observations, feelings, needs, requests. Nonviolent Communication (NVC) is sometimes referred to as compassionate communication. Its purpose is to: 1. create human connections that empower compassionate giving and receiving 2. create governmental and corporate structures that support compassionate giving and receiving. NVC involves both communication skills that foster compassionate relating and consciousness of the interdependence of our well being and using power with others to work together to meet the needs of all concerned. This approach to communication emphasizes compassion as the motivation for action rather than fear, guilt, shame, blame, coercion, threat or justification for punishment. In other words, it is about getting what you want for reasons you will not regret later. NVC is NOT about getting people to do what we want. It is about creating a quality of connection that gets everyone’s needs met through compassionate giving. www.lindavanderlee.com The process of NVC encourages us to focus on what we and others are observing separate from our interpretations and judgments, to connect our thoughts and feelings to underlying human needs/values (e.g. protection, support, love), and to be clear about what we would like towards meeting those needs. These skills give the ability to translate from a language of criticism, blame, and demand into a language of human needs -- a language of life that consciously connects us to the universal qualities “alive in us” that sustain and enrich our well being, and focuses our attention on what actions we could take to manifest these qualities. -

Rachelle Lamb Compassionate Nonviolent Communication

Compassionate Nonviolent Communication Rachelle Lamb Certified NVC Trainer Trainings, Mediation , Practice Groups Private Sessions (Personal & Business) Ph. (250) 480-7122 Website: www.rachellelamb.com e-mail: [email protected] Additional Information Sources Rachelle Lamb www.rachellelamb.com The Center for Nonviolent Communication www.cnvc.org Nonviolent Communication (Book Publisher’s Site) www.nonviolentcommunication.com © Rachelle Lamb, Mindful Communication, Victoria, BC. (250) 480-7122 www.rachellelamb.com 10 W A I T Why Am I Talking? The Importance of Intention We always have an intention when we speak. The question is: are we fully conscious of our intention? Our intention significantly determines the quality of our exchanges. The words we choose to express ourselves are a reflection of our intention. We will develop clarity of intention to the degree that we place our attention on intention. When our intention is to get our way, the relationship is likely to be compromised. When our intention is to create a quality of connection with others where everyone’s needs are valued, collaborative relationships ensue. The purpose of Nonviolent Communication™ is to facilitate a quality of connection with others where everyone’s needs are understood and valued. © Rachelle Lamb, Mindful Communication, Victoria, BC. (250) 480-7122 www.rachellelamb.com 1 Important things we already know and often forget: 1. We can’t change others; we can only change ourselves. 2. When people hear blame or criticism, they will usually shut down and become defensive. 3. When we take things personally, we suffer. 4. Consciously or unconsciously, we choose our responses in every given moment. -

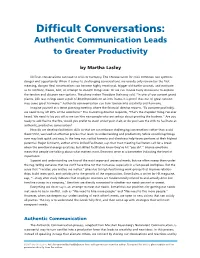

Difficult Conversations: Authentic Communication Leads to Greater Productivity

Difficult Conversations: Authentic Communication Leads to Greater Productivity by Martha Lasley Difficult conversations can lead to crisis or harmony. The Chinese word for crisis combines two symbols: danger and opportunity. When it comes to challenging conversations, we usually only remember the first meaning, danger. Real conversations can become highly emotional, trigger old battle wounds, and motivate us to confront, freeze, bolt, or attempt to smooth things over. Or we can choose lively discussions to explore the tension and discover new options. The piano maker Theodore Steinway said, “In one of our concert grand pianos, 243 taut strings exert a pull of 40,000 pounds on an iron frame. It is proof that out of great tension may come great harmony.” Authentic communication can turn tension into creativity and harmony. Imagine yourself at a tense planning meeting where the financial director reports, “To compete profitably, we need to lay off 20% of the workforce.” The marketing director responds, “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard. We need to lay you off so we can hire new people who are serious about growing the business.” Are you ready to add fuel to the fire, would you prefer to crawl under your chair, or do you have the skills to facilitate an authentic, productive conversation? How do we develop facilitation skills so that we can embrace challenging conversations rather than avoid them? First, we need an effective process that leads to understanding and productivity. While smoothing things over may look quick and easy, in the long run, radical honesty and directness help teams perform at their highest potential. -

How We Talk About How We Talk: Communication Theory in the Public Interest by Robert T

20042004 ICA ICAPresidential Presidential Address Address How We Talk About How We Talk: Communication Theory in the Public Interest by Robert T. Craig This article is a revision of the author’s presidential address to the 54th annual conference of the International Communication Association, presented May 29, 2004, in New Orleans, Louisiana. Using recent public discourse on talk and drugs as an example, it reflects on our culture’s preoccupation with communication and the pervasiveness of metadiscourse (talk about talk for practical purposes) in pri- vate, public, and academic discourses. It argues that communication theory can be used to describe and analyze the common vocabularies of public metadiscourse, critique assumptions about communication embedded in those vocabularies, and contribute useful new ways of talking about talk in the public interest. “Talk to your kids.” “Talk to your kids about drugs.” “Talk to your doctor.” “Talk to your doctor about Ambien.” “Ask you doctor if Lipitor is right for you.” “Ask your doctor if Advair is right for you.” “Talk. Know. Ask.” “Questions: The antidrug.” This collage of quotations selected from recent drug company commercials and antidrug public service announcements highlights a well-known irony in the pub- lic discourse on drugs that is not, however, my main point. Yes, the culture that produced these ads is rather obsessed with drugs. That culture is also rather obsessed with talk or, more generally, with communication. Both obsessions are on display in these ads in interesting juxtaposition. Drugs, in this cultural logic, are powerful and therefore as dangerous as they are desirable. They solve problems and they cause problems. -

Pedagogies of Nonviolent Communication in the Online Classroom

Tammy Wiens, Colloquium Outline, REA 2014 Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary [email protected] • Colloquium Title: Pedagogies of Nonviolent Communication in the Online Classroom • Introduction: At a time when higher education is increasingly delivered through computer mediated instruction, it is crucial to raise awareness of online pedagogies that nurture non-violent interactions among students. Communication within an online classroom is very different from communication in a face-to-face classroom, primarily because dialogue is text-based rather than spoken. This colloquium demonstrates the need to address nonviolent communication as a pedagogical challenge rather than as a technological challenge. The goal of the research is to offer a rubric to guide pedagogies of nonviolent communication in online forums. Not only will pedagogies of nonviolent communication reduce the potential for hurtful language among peers, a rubric for online dialogue will also increase a depth of relationship among participants and enhance the richness of learning in the online community. • Communication Styles: a. Online versus face-to-face I will briefly present the unique features of online communication that present pedagogical challenges that are different from a face-to-face context. There are times when students underestimate the violence conveyed in their written critiques or expressions of disagreement and this can cause a breakdown in the activity system of the class so that the online course ceases to function effectively. The instructor’s role in facilitating nonviolent communication is not always as complex as negotiating students’ prejudicial or inappropriate comments. Less complex, but equally as crucial to maintaining a sustainable learning community are those pedagogies that promote collaboration, social presence, and critical thinking. -

Obtaining Contents of Communications

2013 ORS 165.5401 Obtaining contents of communications (1) Except as otherwise provided in ORS 133.724 (Order for interception of communications) or 133.726 (interception of oral communication without order) or subsections (2) to (7) of this section, a person may not: (a) Obtain or attempt to obtain the whole or any part of a telecommunication or a radio communication to which the person is not a participant, by means of any device, contrivance, machine or apparatus, whether electrical, mechanical, manual or otherwise, unless consent is given by at least one participant. (b) Tamper with the wires, connections, boxes, fuses, circuits, lines or any other equipment or facilities of a telecommunication or radio communication company over which messages are transmitted, with the intent to obtain unlawfully the contents of a telecommunication or radio communication to which the person is not a participant. (c) Obtain or attempt to obtain the whole or any part of a conversation by means of any device, contrivance, machine or apparatus, whether electrical, mechanical, manual or otherwise, if not all participants in the conversation are specifically informed that their conversation is being obtained. (d) Obtain the whole or any part of a conversation, telecommunication or radio communication from any person, while knowing or having good reason to believe that the conversation, telecommunication or radio communication was initially obtained in a manner prohibited by this section. (e) Use or attempt to use, or divulge to others, any conversation, telecommunication or radio communication obtained by any means prohibited by this section. (2) (a) The prohibitions in subsection (1 )(a), (b) and (c) of this section do not apply to: (A) Officers, employees or agents of a telecommunication or radio communication company who perform the acts prohibited by subsection (1 )(a), (b) and (c) of this section for the purpose of construction, maintenance or conducting of their telecommunication or radio communication service, facilities or equipment.