The Automobile Agent in Arcade Fire's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Google Chrome Scores at SXSW Interactive Awards 16 March 2011, by Glenn Chapman

Google Chrome scores at SXSW Interactive awards 16 March 2011, by Glenn Chapman type of video," Google's Thomas Gayno told AFP after the award ceremony. "For Google it is very compelling because it allows us to push the browser to its limits and move the Web forward." Visitors to the website enter addresses where they lived while growing up to be taken on nostalgic trips by weaving Google Maps and Street View images with the song "We Used to Wait." A woman works on her computer as on the wall behind "It takes you on a wonderful journey all is seen the logo of Google in Germany 2005. A music synchronized with music," Gayno said. "It is like and imagery website that shows off capabilities of choreography of browser windows." Google's Chrome Web browser won top honors at a South By Southwest Interactive (SXSW) festival known US Internet coupon deals website Groupon was for its technology trendsetters. voted winner of a People's Choice award in keeping with a trend of SXSW goers using smartphones to connect with friends, deals, and happenings in the real world. A music and imagery website that shows off capabilities of Google's Chrome Web browser won Founded in 2008, Chicago-based Groupon offers top honors at a South By Southwest Interactive discounts to its members on retail goods and (SXSW) festival known for its technology services, offering one localized deal a day. trendsetters. A group text messaging service aptly named The Wilderness Downtown was declared Best of GroupMe was crowned the "Breakout Digital Trend" Show at an awards ceremony late Tuesday that at SXSW. -

Download a PDF of the Program

THE INAUGURATION OF CLAYTON S. ROSE Fifteenth President of Bowdoin College Saturday, October 17, 2015 10:30 a.m. Farley Field House Bowdoin College Brunswick, Maine Bricks The pattern of brick used in these materials is derived from the brick of the terrace of the Walker Art Building, which houses the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. The Walker Art Building is an anchor of Bowdoin’s historic Quad, and it is a true architectural beauty. It is also a place full of life—on warm days, the terrace is the first place you will see students and others enjoying the sunshine—and it is standing on this brick that students both begin and end their time at Bowdoin. At the end of their orientation to the College, the incoming class gathers on the terrace for their first photo as a class, and at Commencement they walk across the terrace to shake the hand of Bowdoin’s president and receive their diplomas. Art by Nicole E. Faber ’16 ACADEMIC PROCESSION Bagpipes George Pulkkinen Pipe Major Grand Marshal Thomas E. Walsh Jr. ’83 President of the Alumni Council Student Marshal Bill De La Rosa ’16 Student Delegates Delegate Marshal Jennifer R. Scanlon Interim Dean for Academic Affairs and William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of the Humanities in Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Delegates College Marshal Jean M. Yarbrough Gary M. Pendy Sr. Professor of Social Sciences Faculty and Staff Trustee Marshal Gregory E. Kerr ’79 Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Board of Trustees Officers of Investiture President Clayton S. Rose The audience is asked to remain seated during the processional. -

The Preludes in Chinese Style

The Preludes in Chinese Style: Three Selected Piano Preludes from Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi and Zhang Shuai to Exemplify the Varieties of Chinese Piano Preludes D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jingbei Li, D.M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven M. Glaser, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Edward Bak Copyrighted by Jingbei Li, D.M.A 2019 ABSTRACT The piano was first introduced to China in the early part of the twentieth century. Perhaps as a result of this short history, European-derived styles and techniques influenced Chinese composers in developing their own compositional styles for the piano by combining European compositional forms and techniques with Chinese materials and approaches. In this document, my focus is on Chinese piano preludes and their development. Having performed the complete Debussy Preludes Book II on my final doctoral recital, I became interested in comprehensively exploring the genre for it has been utilized by many Chinese composers. This document will take a close look in the way that three modern Chinese composers have adapted their own compositional styles to the genre. Composers Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi, and Zhang Shuai, while prominent in their homeland, are relatively unknown outside China. The Three Piano Preludes by Ding Shan-de, The Piano Preludes and Fugues by Chen Ming-zhi and The Three Preludes for Piano by Zhang Shuai are three popular works which exhibit Chinese musical idioms and demonstrate the variety of approaches to the genre of the piano prelude bridging the twentieth century. -

Horseshoes, Heemstra and Hot Dogs

Northwestern College inside this issue longboarding tips PAGE 5 indie album reaches #1 PAGE 6 football heartbreak BEACON PAGE 8 Volume 83 Number 1 September 10, 2010 The Club @ Horseshoes, Heemstra and hot dogs N-Dub: Save BY ERIC SANDBULTE but built as a residence hall CONTRIBUTING WRITER instead.” the Earth Each new school year brings its In the meantime, stranded West own unique set of changes, and this students take refuge in the “West and dance! year is certainly no exception. The Wing” of Stegenga Hall, formally BY JEB RACH building of a new residence hall and First South. CONTRIBUTING WRITER a new volleyball court highlight the The fire pit and volleyball court The Hub @ N-Dub is usually exciting new additions that have are two other new additions to a fairly busy place. But this come to Northwestern’s campus. the campus, thanks to the Student Saturday, the Hub will take it up a Many students have noticed Government Association (SGA) notch with the Club @ N-Dub. the fenced area where Heemstra and the Maintenance Department. All students on campus are was previously located. “That spot Located near Stegenga, they are invited to come to the one and will be left as a continuation of the open for use daily. SGA president only club on campus at the Hub. green,” said Patrick Hummel, the Justin Jansen clarified, “You don’t Sponsored by Student Activities Director of Residence Life. have to make any reservations for Council (SAC), the Club @ N-Dub Construction on a new residence the fire pit or the volleyball court. -

Quadrophonic News Issue 7

Major Album Releases In The Fourth Quarter, 2013: Reflektor -Arcade Fire October 29th, 2013 Artpop -Lady Gaga November 11th, 2013 Live on the BBC Vol. 2 -The Beatles November 11th, 2013 •New -Paul McCartney •Beyoncé -Beyoncé •Matangl -M.I.A. •Because The Internet QUADROPHONIC NEWS •Shangri La -Jake Bugg -Childish Gambino Quadrophonic News December 2013 Issue 7 Female Artists: A Reflection In This Month’s Issue: There's a lot to be said for any vocalist with a truly amazing • Album Reviews: Reflektor, Yeezus, Centipede Hz, voice, but there's undeniably something special about a woman with a MMLP2, Live Through This, Bleach, Night Time, powerful voice and monumental skill in writing. So in this article I hope My Time to pay tribute to some of the best female vocalists/song writers out there. It's a big category so, unfortunately I won't be able to get to every one • Insight On Famous Female Artists I’d like to, but I hope to cover three of my favorites. • December/January Music Event Calendar First up is Patty Griffin. Patty is a powerful song writer from Old Town, Maine. her musical style is hard to pin down but it lands somewhere between folk and rock. Her voice is one of incredible range, Arcade Fire’s Reflektor Review her voice can convey every emotion you can imagine, softly or loudly, Achtung Baby. OK Computer. Sound of Silver. sweetly or harshly, and this amazing voice is accompanied by her Elephant. All of these albums are special. You remember indomitable talent for song writing. -

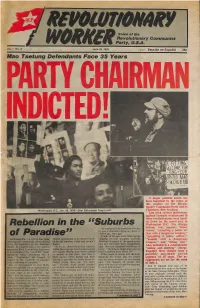

Rebellion in the "Suburbs Washington D.C

RCPi Rmammtm Voice of the Revolutionary Communist mm£RParty, U.S.A. Vol. 1 No. 9 June 29, 1979 oo ^ Seccion en Espahol 25c Mao Tsetung Defendants Face 35 Years PARTY CHAIRMAN INDICTED! V 1 WELCOME OR ENj, the m OFP A major political attack has been launched by the rulers of this country on the Revolu tionary Communist Party and its Washington, D.C., Jan. 29, 1979—Over 500 protest Teng's visit. Chairman, Bob Avakian, Last week, serious indictments against Comrade Avakian and 16 other revolutionaries were hand ed down by the grand jury in Rebellion in the "Suburbs Washington D.C. The charges As evening fell the crowd had swelled include four separate felony to over a thousand taking up chants of counts; '^assaulting a police of of Paradise" "More gas, more gas!" ficer with a dangerous weapon," People of all ages were cheering and "assaulting a police officer," Levitlown, Pa.—A typical blue collar shaped intersection in Levitlown flank clapping for the truckers, excitedly "assault with a dangerous working class community often referred ed by gas stations, stores and people's debating the causes of the gas shortage weapon," and "felony riot." and why the prices were so goddamn 10 by the capitalists as the American homes. Also included is a misdemeanor dream. In a speech just a few months At 6 p.m. about twenty-five truckers high. One man expressed the feelings of "aiding and abetting" charge. ago Henry Ford II pointed to Levitlown pulled their big rigs into the intersection many; "Nothing is happening and we as an example of the *'good life" under and started blaring their horns calling want something done about it!" Together these charges carry a capitalism where everybody has it on people to join them. -

Violin Concerto of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

ERASING THE COLOR LINE: THE VIOLIN CONCERTO OF SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR BY HANGYUL KIM Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2016 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Ayana Smith, Research Director ______________________________________ Mimi Zweig, Chair ______________________________________ Stanley Ritchie ______________________________________ Peter Stumpf 22 September 2016 ii Copyright © 2016 Hangyul Kim iii To my parents iv Acknowledgements I am grateful to my late violin professor, Ik-Hwan Bae, for his guidance during my studies at Indiana University, as well as his family Sung-Mi Im and Subin Bae. I am also grateful to my brother, Hanearl Kim, for always helping me through difficult times and to my parents for their support and encouragement throughout my academic studies. I would also like to thank my committee for seeing me through the final stages of my degree, especially Dr. Ayana Smith, who took the time to patiently proofread my document. Lastly, I am grateful to my partner, Carolyn Gan, for her patience and dedication and love. This paper would never have come into fruition without my experiences at the East Rock Global Magnet Studies School, and I would like to extend my well-wishes to my colleagues and their children, as they forge onwards through a turbulent world. v Preface Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s mixed-black heritage, which easily could have remained a social handicap in 19th century Victorian England, may arguably have boosted his career during a time when African-heritage music and artists became fashionable amongst the European and American public. -

Baixar Baixar

1 9 8 4 - PerCursos 7 2 4 6 It’s just a reflector: Orfeu, o fantasma e a era especular em Reflektor da banda Arcade Fire Resumo O texto trabalha a apropriação do mito de Orfeu e Eurídice no aparato visual Francisco das Chagas Fernandes (notadamente os vídeos) de Reflektor, quarto álbum da banda musical Santiago Júnior canadense Arcade Fire, com objetivo de localizar o momento no qual o mito Doutor em História pela clássico encontrou a reflexão sobre a era das imagens na cultura global Universidade Federal Fluminense atual. A partir de uma análise iconológica, será investigado o uso de – UFF. Professor da Universidade conceitos visuais, especialmente os temas do fantasma, do espelho e da reflexão nas obras audiovisuais produzidas para o álbum da banda, os quais Federal da Universidade Federal tiveram ampla divulgação na internet. do Rio Grande do Norte - UFRN. Brasil Palavras-chave: Arcade Fire; Mito de Orfeu e Eurídice; Cultura visual global. [email protected] Para citar este artigo: SANTIAGO JÚNIOR, Francisco das Chagas Fernandes. It’s just a reflector: Orfeu, o fantasma e a era especular em Reflektor da banda Arcade Fire. Revista PerCursos, Florianópolis, v. 17, n.33, p. 55 – 93, jan./abr. 2016. DOI: 10.5965/1984724617332016055 http://dx.doi.org/10.5965/1984724617332016055 Revista PerCursos, Florianópolis, v. 17, n. 33, p. 55 – 93, jan./abr. 2016. p.55 Per It’s just a reflector: Orfeu, o fantasma e a era especular em Reflektor da banda Arcade Fire Francisco das Chagas Fernandes Santiago Júnior Cursos It’s just a reflector: Orpheus, the ghost and the specular age in Reflektor by Arcade Fire Abstract The text works the aspects of appropriation of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in visual apparatus (mainly the videos) of Reflektor, fourth album by Canadian band Arcade Fire, to meet the moment in which the classic myth merged with reflection about the images age in the actual global culture. -

Students to Vote on Fee Increase This Quarter

VOLUME 47, ISSUE 22 THURSDAY, JANUARY 9, 2014 WWW.UCSDGUARDIAN.ORG !"#$"%%$&'("#) ;=75?/A=;7;>A5 PROPOSED STATE $"*!+,-%.%/#0"%%%1 THE BEST OF BUDGET LEAKED 2013 Students to Vote on Fee A preliminary report for Gov. Jerry Brown’s 2014–15 budget shows increased funding for the UC system, Increase This Quarter but funding falls short of the UC Regents’ request. Here is the proposed budget, broken down by the numbers: $263.1 REQUESTED BY UC REGENTS $120.9 FUNDING SHORTFALL $142.2 FUNDS PROVIDED IN “The Wolf of Wall Street” BUDGET may not stand up against “Gravity.” Read up on the Guardian’s choices for best songs, albums and movies of 2013. ALL 2334356.%%%%/783%%%9 FIGURES IN MILLIONS 2:7;%%%23<=3%%%2>?:>58%%%@A= A&C%%%(,D"$%%%E,C%%!("%%%-"F%%%G"#C ,D+-+,-.%%%/#0"%%%J :AB3%%%?;756 $F+HH+-0%%%(,$!$%%%I#$!%%%H""! $D,C!$.%%%/#0"%%%KL PHOTO BY JOSEPH HO/GUARDIAN FILE A proposed $52 hike on student fees could help pay for FORECAST new transportation options and increase financial aid. 10.8% Increase in total proposed state fund- MN%%8#'C+"II#%%@I"+$*(H#-%%!"#$%&'!()**'+&$("& ing for Calif. higher education from 2013–14 to 2014–15 academic year .S. Council’s proposed transportation fee ref- ments in mass transit and alternative transportation, THURSDAY FRIDAY erendum, which would add a $52 quarterly while the other 29 percent will go to financial aid, as 11.6% H 63 L 44 H 73 L 49 student fee to cover transportation services mandated by a statewide return-to-aid policy. Awill finally be voted on by students Week 8 of Winter “We’ll be leading a big education campaign this Percentage of total proposed 2014–15 Quarter 2014. -

Bye, Bye, Miss American Pie? the Supply of New Recorded Music Since Napster

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES BYE, BYE, MISS AMERICAN PIE? THE SUPPLY OF NEW RECORDED MUSIC SINCE NAPSTER Joel Waldfogel Working Paper 16882 http://www.nber.org/papers/w16882 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2011 The title refers to Don McLean’s song, American Pie, which chronicled a catastrophic music supply shock, the 1959 crash of the plane carrying Buddly Holly, Richie Valens, and Jiles Perry “The Big Bopper” Richardson, Jr. The song’s lyrics include, “I saw Satan laughing with delight/The day the music died.” I am grateful to seminar participants at the Carlson School of Management and the WISE conference in St. Louis for questions and comments on a presentation related to an earlier version of this paper. The views expressed in this paper are my own and do not reflect the positions of the National Academy of Sciences’ Committee on the Impact of Copyright Policy on Innovation in the Digital Era or those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2011 by Joel Waldfogel. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Bye, Bye, Miss American Pie? The Supply of New Recorded Music Since Napster Joel Waldfogel NBER Working Paper No. 16882 March 2011 JEL No. -

Caldas Chs Dr Bauru.Pdf (14.59Mb)

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO” FACULDADE DE ARQUITETURA, ARTES E COMUNICAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO LINHA DE PESQUISA: PRODUÇÃO DE SENTIDO NA COMUNICAÇÃO MIDIÁTICA CARLOS HENRIQUE SABINO CALDAS VIDEOCLIPE INTERATIVO: NOVAS FORMAS EXPRESSIVAS NO AUDIOVISUAL Bauru 2018 CARLOS HENRIQUE SABINO CALDAS VIDEOCLIPE INTERATIVO: NOVAS FORMAS EXPRESSIVAS NO AUDIOVISUAL Tese de Doutorado apresentada ao Programa de pós-graduação em Comunicação da Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação da Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, campus Bauru, para a obtenção do título de doutor, sob a orientação da Professora Doutora Ana Silvia Lopes Davi Médola (Linha de Pesquisa 2: Produção de Sentido na Comunicação Midiática). Bauru 2018 Caldas, Carlos Henrique Sabino. Videoclipe interativo: novas formas expressivas no audiovisual / Carlos Henrique Sabino Caldas, 2018 347 f. : il. Orientador: Ana Silvia Lopes Davi Médola Tese (Doutorado)–Universidade Estadual Paulista. Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação, Bauru, 2018 1. Videoclipe Interativo. 2. Remediação. 3. Hibridismo. 4. Sincretismo de Linguagens. 5. Semiótica. I. Universidade Estadual Paulista. Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação. II. Título. Dedico este trabalho a Deus e a minha família, em especial a minha mãe Rosa. AGRADECIMENTOS Ao meu adorado Deus que me orientou neste caminho; A minha amada esposa Jackeline que me acompanhou em todos os momentos e me motivou dia a dia a prosseguir; Aos meus dois lindos filhos, Lelê -

UA37/44 Tidbits of Kentucky Folklore

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Faculty/Staff Personal Papers WKU Archives Records 1937 UA37/44 Tidbits of Kentucky Folklore Gordon Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/fac_staff_papers Part of the Folklore Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Linguistic Anthropology Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Oral History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Gordon, "UA37/44 Tidbits of Kentucky Folklore" (1937). Faculty/Staff Personal Papers. Paper 171. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/fac_staff_papers/171 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty/Staff Personal Papers by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORIGINALS TIDBITS OF KENTUCKY FOLKLORE by Gordon Wilson Vol. II Nos. 101-199 /\] 0, / ) .C IJ "I J it., tl n 1J • 1 t f, 7 () !_J ( i.n, Lo (" i_ (7 '·'. .l + l. .., ,, cr;nt () _j ,, i, ' -;, ii'" n, plrlr} -,-, l /\Jo, I llc,d :n11l_(i .,. tron int : j { J •• ' 1-; 1 l_i C1)11 l(! i 111 C:O'.l.1c7 ,. ,,-i,nn nf bF;J·n cloor --i t''1 nr1 1 ''. ·,1,,71 'I' I. r· f"'•n ·1 i_ nn --.-.h 11 f'. t .i 1· F;rc.l ji:int h (J 1,i u J. '.-! i_ :i. [J .Jj (JJ of (! l; ov1 ned i_ J' I C) l .l. d () r-: h;__ 1;,- ; ,,_;'_'[ 1 (; l,- 1 i t (j : ' ' '1 I. cc 1 L :i: --~ C I i' /yjJ;¢/. (Vo, v- '() \) _r 11, _r·1,1nnj__ie-;f.· _11J1·; ld en: i-'.' t,)1; t ·el :i_ li.r 01c.1.-fe,:,::;l1ioncc1 Coux·ting /(_! ffothinc ho.fJ cl1b,nc:nd Viore rr::d1cr,,1l;y :i.n the lr;bt L\!fO G:C tl1:cr:1t·: J~ ~ell-br·ed boy did not n~Lr,.